Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Physiology

Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) is a disease in which the lungs become scarred over time. It can result from occupational exposure, genetic defects, acute lung injury, or idiopathic causes. Sensory nerves are responsible for detecting harmful airborne stimuli and provide input to a variety of cells within the lungs, including airways and blood vessels. They play a critical role in regulating cardiopulmonary functions and maintaining homeostasis in healthy lungs. This review discusses the various effects of sensory nerve signaling in the setting of pulmonary fibrosis.

- pulmonary fibrosis

- pulmonary hypertension

- sensory nerves

- cough

1. Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) is a disease in which the lungs become scarred over time. It can result from occupational exposure, genetic defects, acute lung injury, or idiopathic causes. PF may also result from a secondary effect of other diseases, including autoimmune disorders and infections. This debilitating condition is associated with dyspnea, cough, and fatigue [1,2] resulting from impaired gas exchange caused by the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix components [3]. This is characterized by fibroproliferation and mononuclear inflammation. The incidence of PF has increased over the last several decades [4], which may be related to increased smoke and particle inhalation, as well as mineral and dust exposure associated with modern, urban lifestyles. The average life expectancy for an individual after being diagnosed with PF is 3 to 5 years [5]. There is currently no cure for the disease and limited therapy options. Thus, identifying treatments that prevent or slow the progression of this disease is vital to improving human health.

Sensory nerves are responsible for detecting harmful airborne stimuli and provide input to a variety of cells within the lungs, including airways and blood vessels. They play a critical role in regulating cardiopulmonary functions and maintaining homeostasis in healthy lungs. Alterations in the phenotype and sensitivity of these fibers are a hallmark of lung diseases, including asthma, viral infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary fibrosis [6,7]. Despite such changes in function, sensory nerve signaling can downregulate PF [8,9], but the mechanisms through which sensory nerves are modified by and contribute to this disease are just beginning to be explored.

2. Sensory Nerves in the Lungs

Within the lungs, innervation is most dense in extrapulmonary and hilar arteries [10,11,12]. The penetration of sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers varies between species but frequently stops shortly after the lung hilus [13,14]. Sensory/peptidergic fibers, in contrast, are found sparingly in vessels throughout the pulmonary vascular tree, airways, and alveoli [15,16,17,18,19]. Sensory nerves confer information about the local environment to the central nervous system, with their cell bodies located within the dorsal root ganglia [20]. Within the lungs, sensory (peptidergic) fibers play a vital role in regulating cardiopulmonary function under both healthy and disease conditions. These nerves are not homogenous in nature, having different anatomical and physiological phenotypes reflecting their location and purpose, and sensory nerve pattern and density vary with age, tissue, and vascular bed [21,22]. Each of these subtypes provides input to the central nervous system and is capable of driving cardiorespiratory reflexes. Unlike sympathetic nerves, sensory nerves can signal both antidromically and orthodromically, thus facilitating their participation in local axon reflexes independent of efferent signaling from the cell body [23]. Ergo, local stimuli experienced in the tissue, such as mechanical or chemical responses, can lead to neurotransmitter release and signaling independent of the central nervous system.

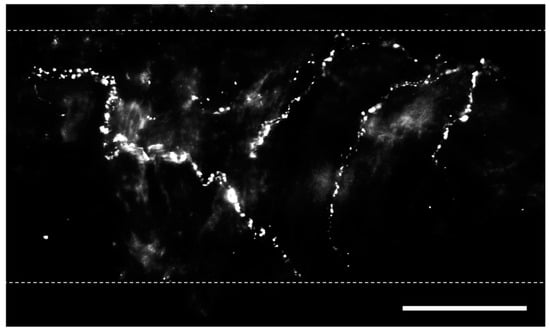

Bronchopulmonary sensory nerves are highly varied based on properties including location in the lungs, ganglionic origin, activation profile, conduction velocity, and responses that nerve activation elicits. Key classes of sensory fibers include nociceptors and mechanosensors. Stretch-sensitive mechanosensors are a group of afferent nerve fibers that respond to the nonharmful distension of the lungs that occurs during respiration [24]. The activation of these fibers is dependent on the rate and depth of breathing (i.e., tidal volume), and they can be grouped into rapidly adapting fibers located in the mucosal layer and slow-adapting fibers located in proximity to SMCs [25]. Nociceptors, in contrast, respond to lung injury and are classified into touch-sensitive cough fibers and bronchopulmonary C fibers [24]. Regardless of fiber type, pulmonary sensory nerves produce biologically active peptides, including substance P, neurokinin A, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) [26], and immunostaining for these transmitters is utilized to identify sensory nerves (Figure 1) [19,27].

Figure 1. Perivascular sensory nerves on mouse pulmonary arteries. Representative calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) staining (maximum z projections) on the surface of a ~100 µm pulmonary artery. Dotted lines indicate approximate vessel edge. Scale bar = 50 µm.

2.1. Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide

CGRP is a 37-amino acid peptide that serves as the primary neurotransmitter released from sensory nerves [28] and is a potent vasodilator [29]. CGRP is synthesized in both central and peripheral sensory neurons and transported along axons in vesicles, where it is released [30]. Subsequently, CGRP can activate G-protein receptor-coupled CGRP receptors in airways and blood vessels [31,32]. These receptors are composed of calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR), receptor activity-modifying protein 1 (RAMP1, the site of ligand binding and specificity), and receptor component protein [33]. CGRP signaling is terminated solely by degradation, as it does not undergo reuptake [28]. Although CGRP signaling can directly stimulate vasodilation in SMCs [31,34,35], an endothelium-dependent pathway that is mediated through nitric oxide signaling can also modulate this response [19,36].

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is released as a co-transmitter with CGRP [37,38]. ATP can activate two types of purinergic receptors, P2X and P2Y, which are located in airway and vascular cells [39,40]. Given the variety of receptor subtypes to which ATP can bind, purinergic signaling can lead to both contractile and dilatory effects on the target tissue [41]. Purinergic receptor expression also varies with vessel size [21]. Unlike CGRP, ATP, which is rapidly broken down into adenosine, can be reuptaken by the cell [42]. However, given that ATP can be released from sympathetic neurons erythrocytes, and other non-neuronal cell types in addition to sensory nerves, [43,44], it can be challenging to identify the source of ATP responsible for paracrine signaling.

2.2. Substance P

Substance P is synthesized in cell bodies within the dorsal root ganglia and transported in vesicles, along with CGRP and ATP, via axons to sensory nerve terminals [28,45]. Following its release, substance P elicits its effect by binding to neurokinin-1 receptors (NK1Rs) coupled to G-protein signaling in airways [46] and in vascular ECs [28,47]. Substance P does not undergo reuptake and, therefore, continues exerting its effects until undergoing enzymatic degradation [45]. Its vascular effects include hyperpolarization and increases in [Ca2+]i in ECs, which activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [47,48]. This causes hyperpolarization and vasorelaxation in SMCs. The dependency of this response on endothelial nitric oxide signaling is demonstrated by the loss of SMC hyperpolarization when the endothelium is disrupted or when eNOS is inhibited in isolated mesenteric arteries [47].

The physiological role of substance P in the vasculature remains controversial. Given that substance P has minimal effects on adjacent SMCs, the levels that reach endothelial cells are not sufficient to alter vessel diameter and permeability in all vascular beds [49]. The exogenous application of substance P has minimal effect on vessel diameter in mesenteric and hepatic vessels [50,51]; however, it can regulate the diameter of pulmonary arteries [52].

2.3. Neurokinin A

Neurokinin A is a 10-amino acid peptide that belongs to the same family of tachykinins as substance P. Neurokinin A has the highest affinity for neurokinin-2 receptors (NK2Rs) [53], although it is also capable of NK1R activation [54]. NK2Rs are present in airways [55], vascular SMCs [56], and ECs [57]. Neurokinin A is a potent bronchoconstrictor [58] but produces a modest pressor response in the vasculature [59]. Neurokinin A is proinflammatory and can also activate macrophages [54].

2.4. Interaction with Sympathetic Nerves

In addition to their direct effects on signaling, sensory perivascular nerves can interact through negative feedback to regulate sympathetic neurotransmission. The peptidergic transmitters CGRP and substance P can reduce the amplitude of sympathetically evoked vasoconstrictions [21]. These effects are mediated by the prejunctional inhibition of sympathetic nerve terminals without affecting downstream signaling pathways [60]. In a reciprocal manner, sympathetic perivascular nerves can inhibit the activity of sensory nerves [61]. In rat mesenteric arteries, norepinephrine (NE) acts on prejunctional α2 adrenoreceptors of sensory nerve terminals to reduce the release of CGRP [62]. ATP released by sympathetic nerves can also bind to P2Y receptors on peptidergic fibers to prevent CGRP signaling [63]. As the presence of sympathetic nerves in the lungs is relatively modest in many organisms, such effects likely vary across species.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms25063538

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!