Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Pharmacology & Pharmacy

Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is a disabling symptom which 60–90 percent of cancer patients with chronic opioid use experience. Peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs) are a class of medications aiming to reverse opioids’ adverse effects on the gut by interacting with opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract without significantly crossing the blood–brain barrier, and therefore they are not affecting the analgesic opioid effects in the central nervous system.

- naldemedine

- naloxegol

- opioid-induced constipation

- obstipation

- cancer patients

1. Introduction

Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) is a disabling symptom which 60–90 percent of cancer patients with chronic opioid use experience [1,2,3,4]. Opioids bring about analgesia largely by binding to μ-receptors in the central nervous system, but they also bind to the μ-receptor in the myenteric plexus in the gastrointestinal tract, leading to the adverse side effect of constipation by decreasing intestinal motility, increasing fluid and electrolyte absorption in the small intestine and the colon, while also increasing the anal sphincter tone [1,2,3,4]. This can lead to more water absorption from the feces resulting in hard and dry stool. OIC has been defined by the Rome IV criteria as worsening symptoms of constipation when initiating, changing, or increasing opioid therapy, and it must include at least two of the following: fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week, straining during more than one-fourth of defecations, lumpy or hard stools in more than one-fourth of defecations, sensation of incomplete evacuation in more than one-fourth of defecations, or manual maneuvers to facilitate more than one-fourth of defecations (e.g., digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor) [5,6].

Peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs) are a class of medications aiming to reverse opioids’ adverse effects on the gut by interacting with opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract without significantly crossing the blood–brain barrier, and therefore they are not affecting the analgesic opioid effects in the central nervous system [7,8,9,10,11,12]. They are different from classic laxatives as, by their mechanism, they are targeted therapies for OIC. PAMORAs have been approved in the US by the Federal Drug Administration for OIC in patients with chronic non-cancer pain [13,14], and in Europe by the European Medicines Agency for use in patients with or without cancer [15,16]. In the US, naloxegol [12.5, 25 mg] was approved in September 2014, and naldemedine [0.1, 0.2 mg] was approved in March 2017 [13,14]. Patients with OIC can suffer greatly from reduced quality of life, as some may reduce their opioid dose in attempts to ease the OIC, leading to inadequate analgesia and a vicious circle without adequate relief of OIC. The American Gastroenterological Association published guidelines for the management of OIC [17], and other societies have published guidelines for the management of constipation in patients with cancer which specifically target OIC by including PAMORAs [18,19].

2. Mechanism of Action

PAMORAs are used in the treatment of opioid-induced constipation because they block and competitively prevent the binding of opioid agonists to μ-opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract [7]. PAMORAs act on gut motility, gut secretion and sphincter function [8]. Opioid agonists induce decreased cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) formation, and this effect is reversed by PAMORAs, leading to normalized chloride secretion. PAMORAs’ effect on gut motility leads to decreased transit time. This reduces the passive absorption of water from the stool, thus allowing for less dry and hard stools [9]. PAMORAs can also prevent sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and anal sphincter dysfunction caused by opioids, reducing straining and incomplete emptying.

3. Structure

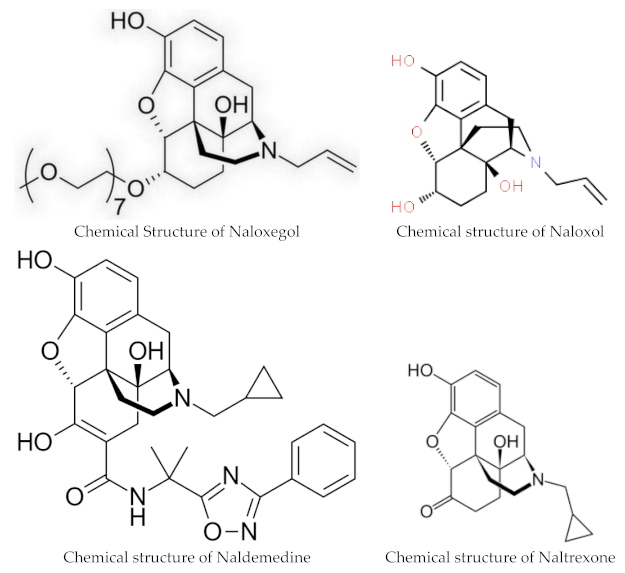

Naloxegol and naldemedine are structurally similar to morphine and other μ-opioid receptor agonists. They both have a pentacyclic structure with a benzene ring, tetrahydrofuran ring, two cyclohexane rings, and a piperidine ring. The phenolic ring and its 3-hydroxyl group play a central role in the analgesic effects of opioids, as removal of the OH group reduces analgesic activity significantly. Naldemedine, with a chemical formula of C32H34N4O6, is a peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist derived from naltrexone. It blocks opioid receptors of the μ, δ, and κ types in the gastrointestinal tract. Patents for naldemedine tosylate are expected to expire between 2026 and 2031. Unlike naltrexone, which can cross the blood–brain barrier and is used to treat opioid dependence, naldemedine has a large hydrophilic side chain and affinity to P-glycoprotein, resulting in minimal concentrations in the central nervous system. Due to its low abuse potential, the Drug Enforcement Administration removed naldemedine from Class II scheduling in September 2017 [20]. Naloxegol oxalate (chemical formula C34H53NO11) is another peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist (PAMORA) and a PEGylated derivative of naloxol, a derivative of naloxone (chemical formula C19H23NO4) [21]. It also does not cross the blood–brain barrier and is not a Class II schedule drug [22].

4. Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of Naldemedine ranges from 20% to 56%, with peak blood plasma levels achieved after 45 min on an empty stomach and 150 min when taken with a high-fat meal. The substance is highly bound to plasma proteins, primarily albumin, in the blood. The recommended dosage is 0.2 mg once daily with or without food [13,15]. Naldemedine is primarily metabolized by CYP3A to nor-naldemedine, and to a lesser extent by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A3 to naldemedine 3-Glucuronide. Both metabolites are opioid receptor antagonists, but they are less potent than the original drug [23]. The drug is excreted in urine and feces, with an elimination half-life of 11 h. Patients with severe hepatic impairment should avoid naloxegol or naldemedine, although both drugs have been found to be safe and effective for those with mild to moderate hepatic impairments [24,25].

Naldemidine requires no adjustment for renal impairment [13,24,26]. For naloxegol, it is recommended that patients with a creatinine clearance <60 mL/min start with the lower naloxegol dose of 12.5 mg once daily and then, if tolerated, can increase the dose to 25 mg once daily [14,27].

Naloxegol clears mostly via hepatic metabolism (P450-CYP3A) with unknown actions of the metabolites. Naloxegol is excreted mostly in feces (and to some degree in urine), and its elimination half-life is 6–11 h [14]. Like naldemedine, when naloxegol is given with a fatty meal, absorption increases. Naloxegol is given as a once daily 12.5 or 25 mg tablet daily, and it should be taken on an empty stomach 1 h before or 2 h after the first meal of the day. Naloxegol may be crushed and can be given via nasogastric tube [14]. Maintenance laxatives should be discontinued prior to starting PAMORA therapy but may be resumed if OIC persists after 3 days of daily treatment. Decreased need for other laxatives may significantly reduce pill burden as, in many studies, PAMORAs alone were sufficient for relief of OIC.

5. Interactions

Even though PAMORAs in the US were approved for treatment of OIC in adults with noncancer pain, they have also been approved in other countries for both cancer and non-cancer pain [15,16], and are often prescribed off-label for OIC in cancer patients in the US. A very low risk of opioid withdrawal exists, so patients starting PAMORAs should be monitored for withdrawal symptoms such as hyperhidrosis, rhinorrhea, anxiety, and chills, though this was not commonly observed in clinical real-world practice. Opioid antagonists such as naloxone and naltrexone should not be used in conjunction with PAMORAs because of the potential increased risk of withdrawal. Both Naldemidine and naloxegol are no longer considered Schedule II controlled substances [20,22].

Naldemedine undergoes primary metabolism by the liver enzyme CYP3A4. Inhibitors of this enzyme can elevate naldemedine levels in the body, potentially leading to more side effects (see Table 1). Drugs like itraconazole, ketoconazole, clarithromycin, and grapefruit juice are examples of such inhibitors. In contrast, substances such as rifampicin and St John’s wort, which induce CYP3A4 activity, can significantly decrease naldemedine concentrations.

Table 1. Inhibitors and inducers of CYP3A4 which potentially increase or decrease naldemedine concentrations.

| Strong Inhibitors of CYP3A4: Increase Naldemedine Concentration | Inducers of CYP3A4: Decrease Naldemedine Concentration |

|---|---|

| Itraconazole | Rifampine |

| Ketoconaxole | St. John’s wort |

| Clarithromycin | |

| Grapefruit juice | |

| Moderate Inhibitors of CYP3A4: Diltiazem Erythromycin Verapamil |

Potent inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein pump, like ciclosporin, have the potential to elevate naldemedine blood levels.

6. Contraindications

Both naloxego and naldemidine are contraindicated in patients with gastrointestinal obstruction or patients with hypersensitivity to the medication. Naloxegol should be avoided with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors like clarithromycin and ketoconazole, as they can raise Naloxegol levels and increase the risk of side effects. If taking moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as diltiazem, erythromycin, or verapamil, the dosage of Naloxegol needs to be reduced. Grapefruit and grapefruit juice may also increase Naloxegol levels. Rifampin, a CYP3A4 inducer, may reduce the effectiveness of Naloxegol.

7. Side Effects

The most common side effects of PAMORAs are diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, flatulence, vomiting and headache [7]. As pure opioid antagonists, Naloxegol and Naldemedine have no potential for abuse. During subgroup analysis of the COMPOSE trials I–III, no increase in adverse events (45.9%) for patients aged ≥65 years (N = 344) were found for naldemedine 0.2 mg compared to the overall group (47.1%) or compared to the placebo (51.6%), nor was there a difference in proportion of responders between older adults compared to the overall group [28]. Other subgroup analyses also found no increase in adverse events for naldemedine users with renal impairments [26] or in patients with hepatobiliary impairments from pancreatic cancer [29]. Moderate and strong CYP3A4 inhibitors and P-glycoprotein inhibitors may increase naldemedine concentrations; therefore, monitoring for adverse reactions is recommended in patients taking these medications. PAMORAs can improve quality of life, are generally safe and well tolerated, and offer a good response without reducing opioid-mediated analgesia.

8. Clinical Trials

Naldemedine was approved based on the results of the Japanese-led COMPOSE trials, which were phase three clinical studies in adult outpatients with chronic non-cancer pain and opioid-induced constipation. COMPOSE-I and COMPOSE-II were 12-week double-blind multi-country randomized controlled trials comparing 0.2 mg oral once daily naldemedine with a placebo between 2013–2015 [30]. Responders had to have at least three spontaneous bowel movements per week, with an increase of one spontaneous bowel movement for nine of the twelve weeks; the proportion of responders were significantly higher in the naldemedine group in both trials. COMPOSE-III tested the long term safety of naldemedine in patients with non-cancer chronic pain over 52 weeks, finding a statistically significant increase in weekly bowel movements without any evidence of opioid withdrawal symptoms [31].

While there is ample literature on the use of PAMORAs in patients with non-cancer pain, recruiting seriously ill patients with cancer into clinical research trials outside of cancer-directed treatment trials is difficult due to the patients’ short life expectancy, impaired functional status, and high symptom burden [32,33].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pharmacy12020048

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!