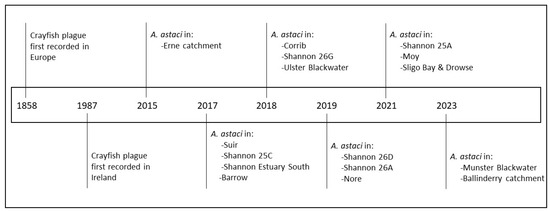

Crayfish plague is a devastating disease of European freshwater crayfish and is caused by the oomycete Aphanomyces astaci (A. astaci), believed to have been introduced to Europe around 1860. All European species of freshwater crayfish are susceptible to the disease, including the white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes. A. astaci is primarily spread by North American crayfish species and can also disperse rapidly through contaminated wet gear moved between water bodies. This spread, coupled with competition from non-indigenous crayfish, has drastically reduced and fragmented native crayfish populations across Europe. Remarkably, the island of Ireland remained free from the crayfish plague pathogen for over 100 years, providing a refuge for A. pallipes. However, this changed in 1987 when a mass mortality event was linked to the pathogen, marking its introduction to the region.

- crayfish plague

- Aphanomyces astaci

- Austropotamobius pallipes

- invasive species

- Ireland

1. Introduction

2. Aphanomyces astaci in Ireland

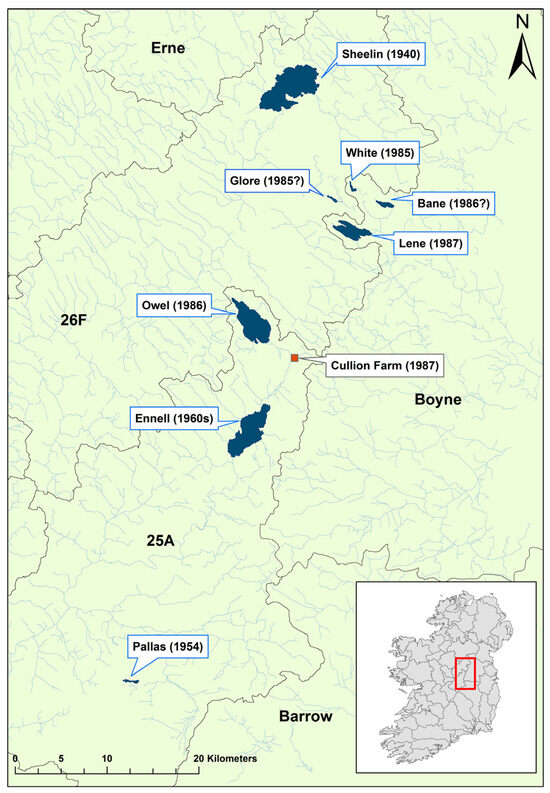

2.1. Historical Incidence of Crayfish Plague in Ireland

2.2. Recent Cases of Crayfish Plague in Ireland

2.3. Reservoir Species and Alternative Host of Aphanomyces astaci

2.4. The Genetic Lineages of Aphanomyces astaci in Ireland

3. The Distribution of Aphanomyces astaci across Ireland

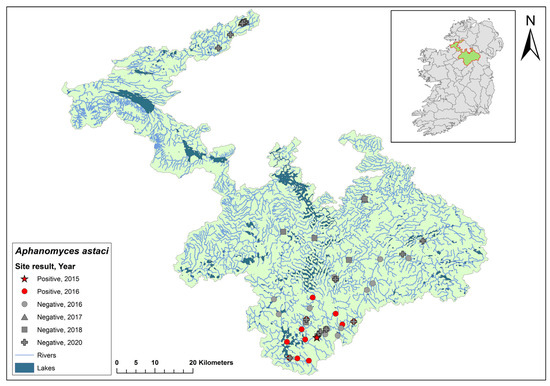

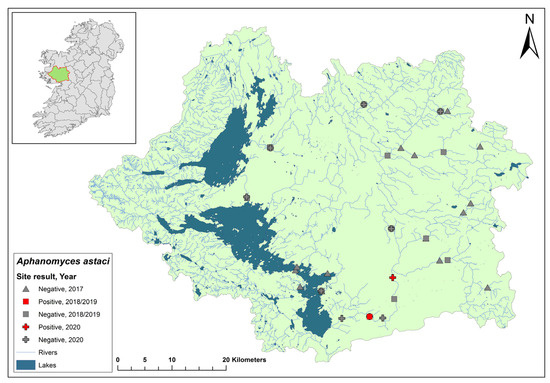

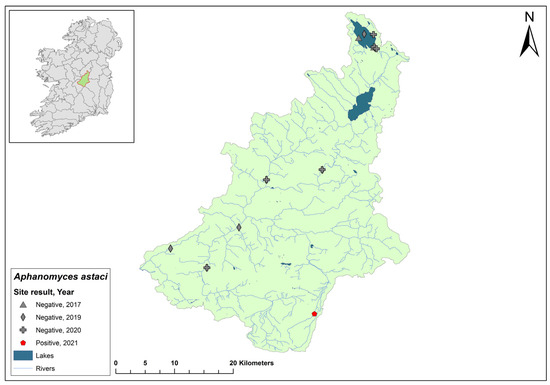

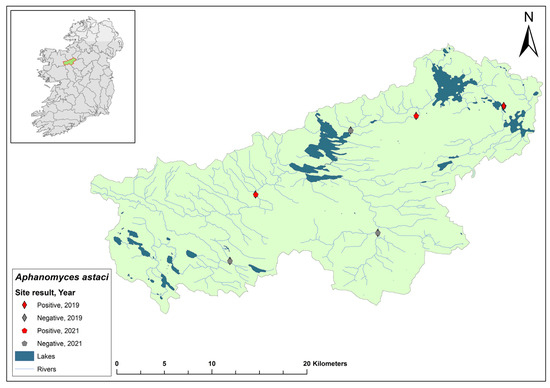

3.1. The Erne Catchment

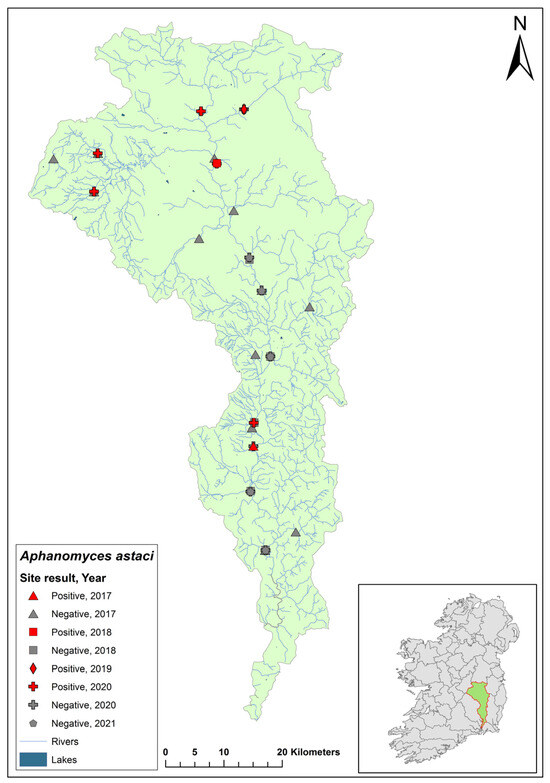

3.2. Barrow Catchment

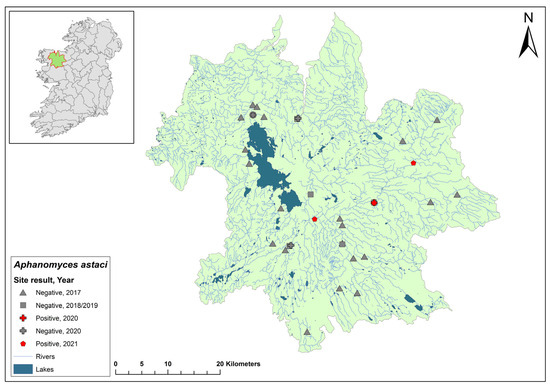

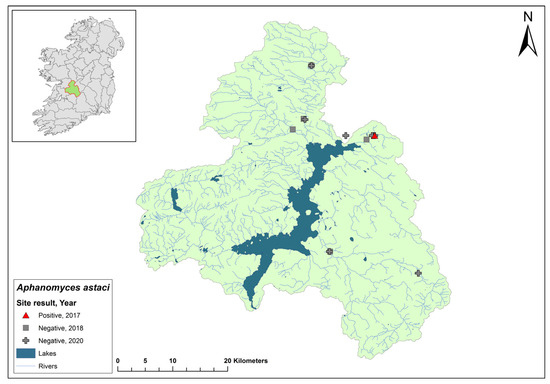

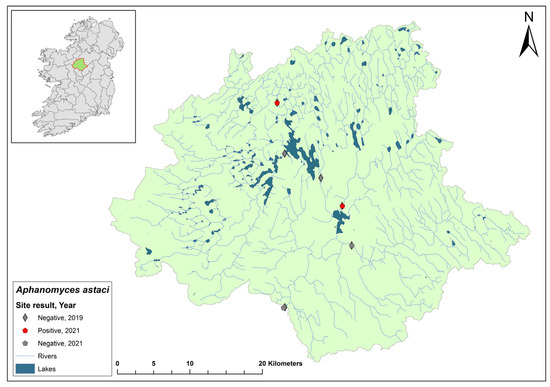

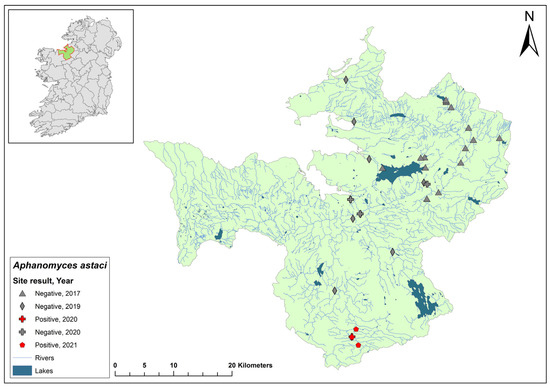

3.3. Corrib Catchment

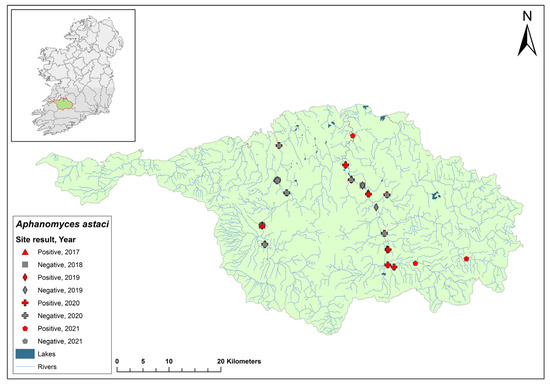

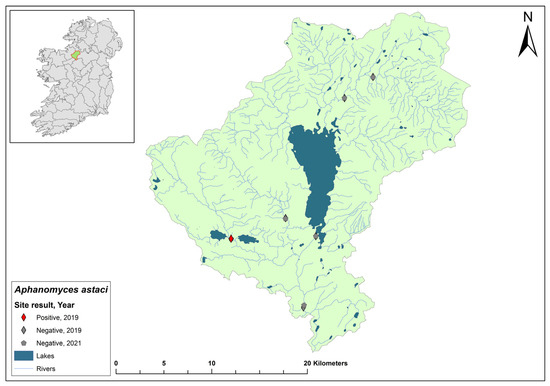

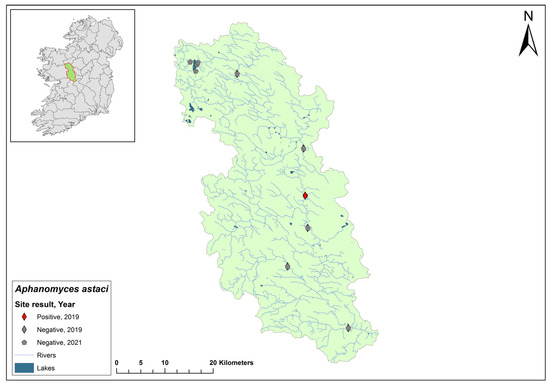

3.4. Moy & Killala Bay Catchment

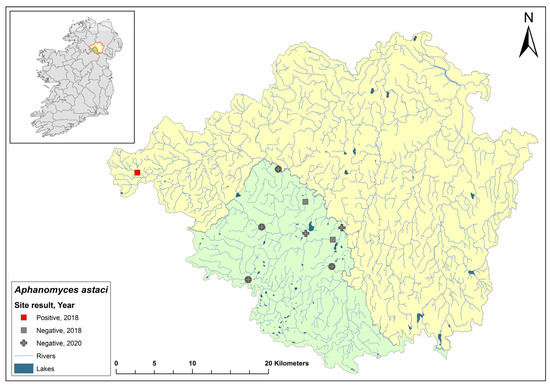

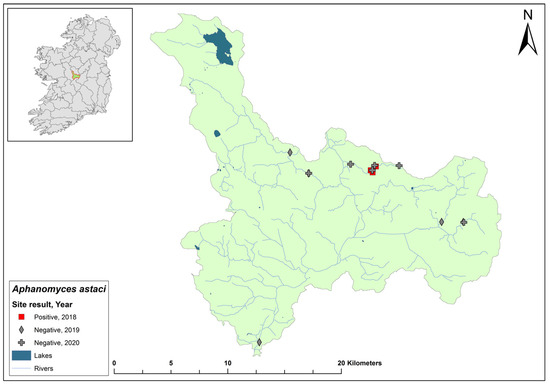

3.5. Nore Catchment

3.6. Shannon Estuary South Catchment

3.7. Lower Shannon (Brosna) 25A Catchment

3.8. Lower Shannon (Lough Derg) 25C Catchment

3.9. Ulster Blackwater Catchment

3.10. Upper Shannon (Lough Allen) 26A Catchment

3.11. Upper Shannon (Boyle) 26B Catchment

3.12. Upper Shannon 26C

3.13. Upper Shannon (Suck) 26D Catchment

3.14. Shannon 26G Catchment

3.15. Sligo Bay & Drowse Catchment

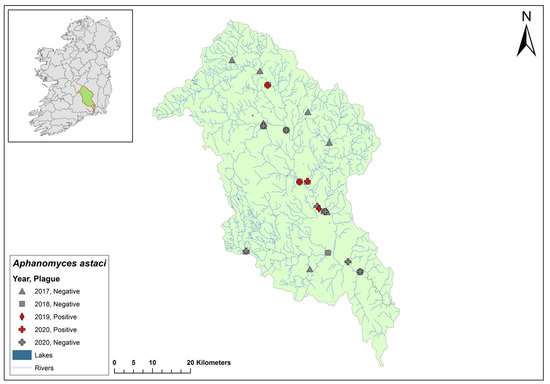

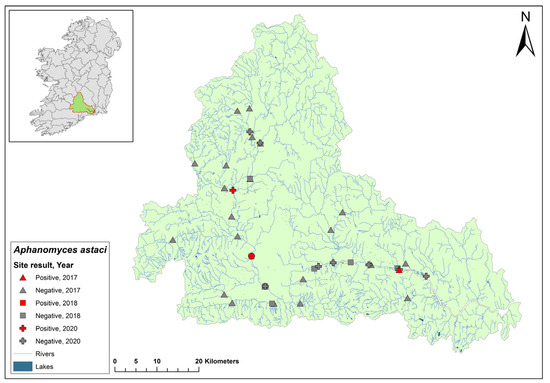

3.16. Suir Catchment

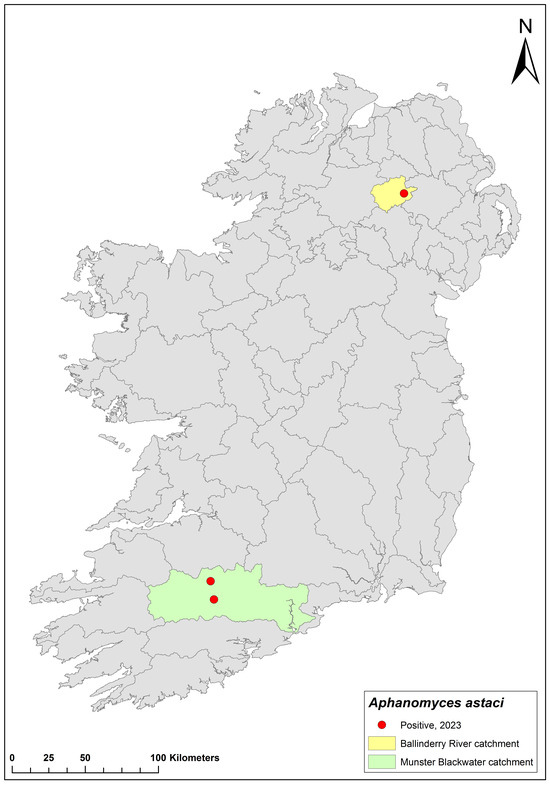

3.17. Outbreaks between 2021 and 2023

4. Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species

4.1. Legislative Changes Regarding Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species

4.2. Wild, Established Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species in Ireland

4.3. No Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species Found during the 2016–2021 Surveys

4.4. The Sale of Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species in Ireland through the Pet Trade

5. Management and Mitigation Strategies

Authorities in both Ireland and Northern Ireland appear to have taken a laissez-faire non-intervention approach to the management of NICS and A. astaci. Research funding related to A. astaci in Ireland has primarily focused on monitoring and determining the spread of the plague pathogen across water catchments; a surveillance programme was established without a mitigation or management programme. Yet, surprisingly, proactive restrictions have not been imposed, such as limiting the movement of wet gear and watercrafts between waterbodies during active mass mortality events. While efforts were taken to publicise the initial plague event and subsequent outbreaks, including a detailed press release by Inland Fisheries Ireland [17], the emphasis has largely been on passive voluntary preventative measures. “Voluntary bans’’ were placed, extended, and lifted on several waterbodies.

The data indicate that the voluntary bans were ineffective at curbing the spread of A. astaci, and this measure was criticised by stakeholders, including the angling community, for not adequately protecting A. pallipes [37][38]. Stakeholders received advice on the “Check, Clean, Dry” protocol when transitioning between watercourses, and similar literature and videos were disseminated online [39][40]. Signs informing the public about crayfish plague and detailing the protocol were prominently placed at high-traffic watercourses. Yet, the continued spread of A. astaci to new catchments suggests these passive measures have been ineffective.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms12010102

References

- Jussila, J.; Francesconi, C.; Theissinger, K.; Kokko, H.; Makkonen, J. Is Aphanomyces astaci Loosing its Stamina: A Latent Crayfish Plague Disease Agent from Lake Venesjärvi, Finland. Freshw. Crayfish 2021, 26, 139–144.

- Jussila, J.; Edsman, L.; Maguire, I.; Diéguez-Uribeondo, J.; Theissinger, K. Money kills native ecosystems: European crayfish as an example. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 648495.

- Cornalia, E. Sulla malattia dei gamberi. Atti Soc. Ital. Sci. Nat. 1860, 2, 334–336.

- Unestam, T. Resistance to the crayfish plague in some American, Japanese and European crayfishes. Rep. Inst. Freshw. Res. Drottningholm 1969, 49, 202–209.

- Unestam, T.; Weiss, D.W. The host-parasite relationship between freshwater crayfish and the crayfish disease fungus Aphanomyces astaci: Responses to infection by a susceptible and a resistant species. Microbiology 1970, 60, 77–90.

- Rezinciuc, S.; Sandoval-Sierra, J.V.; Oidtmann, B.; Diéguez-Uribeondo, J. The Biology of Crayfi sh Plague Pathogen Aphanomyces astaci: Current Answers to Most Frequent Questions. In Freshwater Crayfish; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 182–204.

- Cerenius, L.; Bangyeekhun, E.; Keyser, P.; Söderhäll, I.; Söderhäll, K. Host prophenoloxidase expression in freshwater crayfish is linked to increased resistance to the crayfish plague fungus, Aphanomyces astaci. Cell. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 353–357.

- Becking, T.; Kiselev, A.; Rossi, V.; Street-Jones, D.; Grandjean, F.; Gaulin, E. Pathogenicity of animal and plant parasitic Aphanomyces spp. and their economic impact on aquaculture and agriculture. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2022, 40, 1–18.

- Boštjančić, L.L.; Francesconi, C.; Rutz, C.; Hoffbeck, L.; Poidevin, L.; Kress, A.; Jussila, J.; Makkonen, J.; Feldmeyer, B.; Bálint, M.; et al. Host-pathogen coevolution drives innate immune response to Aphanomyces astaci infection in freshwater crayfish: Transcriptomic evidence. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 600.

- Strand, D.A.; Jussila, J.; Viljamaa-Dirks, S.; Kokko, H.; Makkonen, J.; Holst-Jensen, A.; Viljugrein, H.; Vrålstad, T. Monitoring the spore dynamics of Aphanomyces astaci in the ambient water of latent carrier crayfish. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 160, 99–107.

- Souty-Grosset, C.; Haffner, P.; Reynolds, J.D.; Noel, P.Y.; Holdich, D.M. Atlas of crayfish in Europe; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle: Paris, France, 2006; p. 188.

- Ungureanu, E.; Mojžišová, M.; Tangerman, M.; Ion, M.C.; Pârvulescu, L.; Petrusek, A. The spatial distribution of Aphanomyces astaci genotypes across Europe: Introducing the first data from Ukraine. Freshw. Crayfish. 2020, 25, 77–87.

- Makkonen, J.; Jussila, J.; Kortet, R.; Vainikka, A.; Kokko, H. Differing virulence of Aphanomyces astaci isolates and elevated resistance of noble crayfish Astacus astacus against crayfish plague. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2012, 102, 129–136.

- Reynolds, J.D. Crayfish in Irish Rivers. In Ireland’s Rivers; Kelly-Quinn, M., Reynolds, J.D., Eds.; University College Dublin Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2020; pp. 95–107.

- Matthews, M.A.; Reynolds, J.D. A population study of the white-clawed crayfish Austropotamobius pallipes (Lereboullet) in an Irish reservoir. In Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy; Royal Irish Academy: Dublin, Ireland, 1995; pp. 99–109.

- Reynolds, J.D. Crayfish extinctions and crayfish plague in central Ireland. Biol. Conserv. 1988, 45, 279–285.

- Inland Fisheries Ireland, Press Release. Investigation Underway into Cause of Crayfish Plague on River Bruskey, near Ballinagh, Co Cavan. 2015. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/ycsn72fr (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Mirimin, L.; Brady, D.; Gammell, M.; Lally, H.; Minto, C.; Graham, C.T.; Slattery, O.; Cheslett, D.; Morrissey, T.; Reynolds, J.; et al. Investigation of the first recent crayfish plague outbreak in Ireland and its subsequent spread in the Bruskey River and surrounding areas. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2022, 423, 13.

- Schrimpf, A.; Schmidt, T.; Schulz, R. Invasive Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) transmits crayfish plague pathogen (Aphanomyces astaci). Aquat. Invasions 2014, 9, 203–209.

- Svoboda, J.; Mrugała, A.; Kozubíková-Balcarová, E.; Kouba, A.; Diéguez-Uribeondo, J.; Petrusek, A. Resistance to the crayfish plague pathogen, Aphanomyces astaci, in two freshwater shrimps. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 121, 97–104.

- Tilmans, M.; Mrugała, A.; Svoboda, J.; Engelsma, M.Y.; Petie, M.; Soes, D.M.; Nutbeam-Tuffs, S.; Oidtmann, B.; Roessink, I.; Petrusek, A. Survey of the crayfish plague pathogen presence in the Netherlands reveals a new Aphanomyces astaci carrier. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 120, 74–79.

- Putra, M.D.; Bláha, M.; Wardiatno, Y.; Krisanti, M.; Yonvitner Jerikho, R.; Kamal, M.M.; Mojžišová, M.; Bystřický, P.K.; Kouba, A.; Kalous, L. Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) and crayfish plague as new threats for biodiversity in Indonesia. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. 2018, 28, 1434–1440.

- Minchin, D. First Irish record of the Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis (Milne-Edwards, 1854) (Decapoda: Crustacea). Ir. Nat. J. 2006, 28, 303–304.

- Klotz, W.; Miesen, F.W.; Hüllen, S.; Herder, F. Two Asian fresh water shrimp species found in a thermally polluted stream system in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Aquat. Invasions 2013, 8, 333–339.

- Huang, T.S.; Cerenius, L.; Söderhäll, K. Analysis of genetic diversity in the crayfish plague fungus, Aphanomyces astaci, by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Aquaculture 1994, 126, 1–9.

- Minardi, D.; Studholme, D.J.; van der Giezen, M.; Pretto, T.; Oidtmann, B. New genotyping method for the causative agent of crayfish plague (Aphanomyces astaci) based on whole genome data. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2018, 156, 6–13.

- Di Domenico, M.; Curini, V.; Caprioli, R.; Giansante, C.; Mrugała, A.; Mojžišová, M.; Cammà, C.; Petrusek, A. Real-Time PCR assays for rapid identification of common Aphanomyces astaci genotypes. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 597585.

- European Union (Invasive Alien Species) (Freshwater Crayfish) Regulations 2018 in, S.I. No. 354 of 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2018/si/354/made/en/print (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Sweeney, P.; Reynolds, J.; Nelson, B.; O’Flynn, C. First recorded population of the Common Yabby (Cherax destructor Clark) (Decapoda, Parastacidae) in the wild in Ireland. Ir. Nat. J. 2022, 39, 14–19.

- Svoboda, J.; Mrugała, A.; Kozubíková-Balcarová, E.; Petrusek, A. Hosts and transmission of the crayfish plague pathogen Aphanomyces astaci: A review. J. Fish Dis. 2017, 40, 127–140.

- Mrugała, A.; Veselý, L.; Petrusek, A.; Viljamaa-Dirks, S.; Kouba, A. May Cherax destructor contribute to Aphanomyces astaci spread in Central Europe? Aquat. Invasions 2016, 11, 459–468.

- Swords, F.; Griffin, B.; White, S.; Cheslett, D.; Geary, M.; Brenan, A.; Coakley, C.; Nelson, B. The National Crayfish Plague Surveillance Program, Ireland—2020–2021; Marine Institute: Galway, Ireland; p. 38.

- Mrugała, A.; Kozubíková-Balcarová, E.; Chucholl, C.; Cabanillas Resino, S.; Viljamaa-Dirks, S.; Vukić, J.; Petrusek, A. Trade of ornamental crayfish in Europe as a possible introduction pathway for important crustacean diseases: Crayfish plague and white spot syndrome. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 1313–1326.

- Panteleit, J.; Keller, N.S.; Kokko, H.; Jussila, J.; Makkonen, J.; Theissinger, K.; Schrimpf, A. Investigation of ornamental crayfish reveals new carrier species of the crayfish plague pathogen (Aphanomyces astaci). Aquat. Invasions 2017, 12, 77–83.

- Faulkes, Z. A bomb set to drop: Parthenogenetic Marmorkrebs for sale in Ireland, a European location without non-indigenous crayfish. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2015, 6, 111.

- Faulkes, Z. Slipping past the barricades: The illegal trade of pet crayfish in Ireland. Biol. Environ. PRIA 2017, 117, 15–23.

- Brazier, B. Off the Scale. White-Clawed Crayfish & Crayfish Plague, Off the Scale Magazine, November 2017. Available online: https://www.offthescaleangling.ie/the-science-bit/crayfish-plague/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Brazier, B. Off the Scale. First Crayfish Plague Outbreak of 2019. Off the Scale Magazine, 21 May 2019. Available online: https://www.offthescaleangling.ie/news/maigue-crayfish/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Invasive Species Ireland. Check, Clean, Dry. Ireland, I.S.N. Check Clean Dry Resources. 2023. Available online: https://invasives.ie/biosecurity/check-clean-dry/56 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Invasive Species Northern Ireland. Check, Clean, Dry. 2023. Available online: https://invasivespeciesni.co.uk/what-can-i-do/check-clean-dry/ (accessed on 11 November 2023).