1. Structure and Methods for Preparing [M(Salen)] Complexes and Their Polymers

1.1. Monomeric Complexes

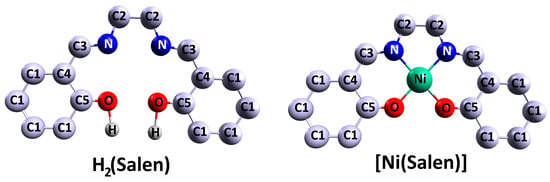

Schiff bases derived from salicylic aldehyde and its derivatives, specifically N,N’-ethylene-bis(salicylimine), C

16H

16N

2O

2 or H

2(Salen), commonly referred to as the salen ligand, are widely used in practical applications (

Figure 1). The salen ligand consists of two C

6H

5OH phenolic groups linked by an ethylenediamine bridge of –N–C(H

2)–C(H

2)–N– and is formed by combining two equivalents of salicylic aldehyde with one equivalent of ethylenediamine. The structure of the molecule consists of several isomers, which differ in the position of the two hydrogen atoms and also in the mutual orientation of the two benzene moieties. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal that the most energetically favorable isomer features a C

2 symmetry configuration and two phenolic groups [

57]. It was demonstrated that the energy stabilization of this isomer is a result of two strong intramolecular N⋯H hydrogen bonds. Furthermore, the out-of-plane distortion of benzene moieties in all isomers is negligible.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the H

2(Salen) salen ligand and [Ni(Salen)] molecular complex [

46].

Let us consider the structure of [M(Salen)] complexes (M = transition metal such as V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Pd) using the example of the monomer N,N′-ethylene-bis(salicylaldiminato)nickel(II), NiO

2N

2C

16H

14 (hereafter [Ni(Salen)]). The [Ni(Salen)] is considered a standard representation of complex 3

d-atom monomers with Schiff bases [M(Schiff)] (

Figure 1) [

18,

45,

58,

59]. The molecule consists of a nickel atom bound to a tetradentate N

2O

2 ligand of the salen type forming an almost planar coordination center [NiN

2O

2] with C

2v symmetry. Geometrically, it is close to a square, since the interatomic distances R (Ni–O) = 1.882 Å and R (Ni–N) = 1.889 Å are close to each other [

18]. Two C

6H

5O-phenyl groups are located at the periphery of the ligand. The square–planar symmetry of [M(Salen)] complexes and the [MN

2O

2] donor coordination center present in them enable the complexes to be involved in various types of intermolecular interactions and in the formation of supramolecular structures.

Currently, it is possible to prepare [M(Salen)] complexes using (i) metal alkoxides (M(OR)

n), (ii) metal amides M(NMe

2)

4, (iii) a two-step reaction involving deprotonation of Schiff bases using lithium bases (CH

3Li, C

4H

9Li) and sequential reaction with metal halides, (iv) alkyl metal complexes M(CH

3), and (v) M(OAc)

2 metal acetates through heating a Schiff base in the presence of a metal salt under boiling conditions [

45,

46,

49,

50,

51].

Considerable attention has been given lately to the synthesis and analysis of new coordination compounds based on [M(Salen)], in which the environment of the metal atom M has been modified by the addition of atomic groups chemically bonded to the salen ligand atoms or to the metal atom. This modification enables the advancement of electroactive photosensitive materials, including nanocomposites, towards higher efficiency [

14,

25,

26,

30,

32,

34,

35].

1.2. Polymers Prepared by Electropolymerization of [M(Salen)] Monomeric Molecules

The first studies of polymers based on transition metal complexes with salen-type Schiff ligands were largely focused on characterizing electrochemical methods for obtaining conducting polymer layers on an electrode from monomers and studying the conductive properties of the resulting polymers using electrometric methods depending on the solvent and type of ligand. It was demonstrated in [

19,

20] that these complexes are reversibly oxidized in strong-donor solvents and oxidatively polymerized in solvents with weak donors. The monomers’ oxidation mechanisms were analyzed using cyclic voltammetry and scanning electron microscopy. It has been shown that the polymer layer’s thickness on the electrode increases linearly over several voltammetric scans. Also, the initial growth rate of the polymer layer increases linearly with rising monomer concentration in the electrolyte solution.

Despite a significant amount of research into the structure and properties of electrically conductive redox polymers poly-[M(Salen)], and in particular poly-[Ni(Salen)], there is no consensus on the mechanism of polymerization of monomer molecules [

1,

2,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

19,

20,

21,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

40,

41,

42,

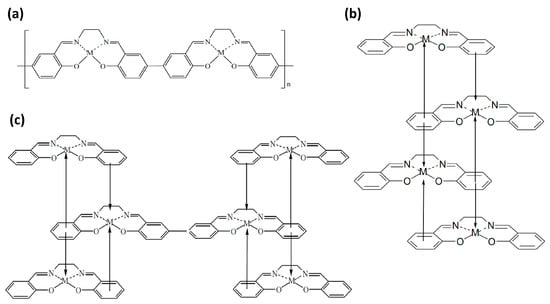

43]. The first model assumes chemical linkage between the phenyl groups of the ligands of neighboring molecules (chainlike structure). In this instance, the polymer forms through the formation of covalent C–C bonds between carbon atoms in the para positions of the phenyl moieties (

Figure 2a) and is inherently purely liganded. [

19,

24]. The second model of the polymerization mechanism is based on processes associated with the metal atom, which we will consider using the example of nickel [

21,

60]. In this case, the complexing nickel cation Ni(II) is first additionally oxidized Ni(II) → Ni(III) + e

−. Subsequently, it can form a stacklike structure which is stabilized by chemical bonding (and charge transfer) between the nickel cation and the phenyl moieties of neighboring monomer molecules (as shown in

Figure 2b). Finally, the third model combines the two previous ones: the electro-oxidation of monomers leads to the formation of stacklike structures. These structures are then cross-linked through the formation of covalent C–C bonds, leading to the appearance of π-conjugated chains involving the phenyl rings of the ligand (

Figure 2c) [

21,

60].

Figure 2. Models of poly-[M(Salen)] structure: (a) chain-like structure; (b) stack-like structure; and (c) hybrid variant.

Over the past 20 years, two contrasting viewpoints regarding the electrochemical activity of conducting polymers have been significantly discussed, in which two options are considered as redox positions (places where redox reactions occur): cations of metal atoms [

20,

21] or ligand atoms [

22,

23]. Over these two decades, different groups of researchers have studied salen complexes and polymers based on them using voltammetry and chronoamperometry [

11,

12],

in situ UV–vis and IR spectroscopy [

11,

13],

in situ ellipsometry [

12], electrochemical quartz microbalances [

12,

14,

15], and impedance spectroscopy [

16]. Both mechanisms are characterized by different charge transfer in [Ni(Salen)] and, as a consequence, different charge states of Ni, N, O, and C atoms in the reduced (neutral) and oxidized states of poly-[Ni(Salen)]. To directly identify nickel atoms in a highly oxidized state within redox polymers, the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) technique was used [

12,

14,

23,

24,

40]. The conducted measurements did not detect highly oxidized Ni(III) atoms within the polymer. This led the authors of these studies to choose the first model, based on the processes of oxidation and reduction of ligands, for the mechanism of polymerization and electrochemical activity of polymers. In [

21], it was also suggested that the polymerization mechanism of [M(Salen)] monomer molecules, involving a metal cation, could occasionally be accompanied by the direct linking of ligands from different monomer molecules (the first model of polymerization). Nevertheless, the results of all these studies did not provide sufficient evidence to make a conclusive decision regarding the polymerization mechanism models described.

Electropolymerization of monomeric [M(Salen)] molecules is usually performed using potentiostatic and potentiodynamic methods, as well as galvanostatic charging [

61]. The polymer film thickness of poly-[M(Salen)] can be easily controlled by the polymerization charge (for potentiostatic methods) or the number of charge–discharge cycles (for potentiodynamic methods) [

61]. In addition, layer-by-layer polymerization of metal salens is also possible [

62].

2. Preparation of Composites Based on [M(Salen)] and Carbon Nanomaterials

Carbon materials have found applications in many fields of science, industry, medicine, etc., due to the variety of allotropic forms with unique physical and chemical properties [

63]. At the same time, the discovery of 0D, 1D, and 2D carbon nanomaterials such as fullerenes, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene marked a breakthrough in materials science and nanotechnology. It should be noted that carbon nanomaterials have become widespread not only as an independent functional material but also as a basis or modifying additive for the preparation of composites with metal compounds, polymers, biomolecules, etc. In this review section, carbon nanotubes and graphene are considered to be the most widely used in the preparation of composites based on [M(Salen)] complexes and carbon nanomaterials.

2.1. Nanotubes and Graphene as a Promising Basis for Composites

CNTs and graphene have attracted considerable attention due to their exceptional surface area and impressive electrical, mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties. These materials have diverse applications, such as catalysis, sensor technologies, and energy storage and conversion. Additionally, they offer significant potential for use in solar cells and fuel cells [

64,

65,

66,

67].

Table 1 presents a summary of the essential properties of these materials for comparative analysis.

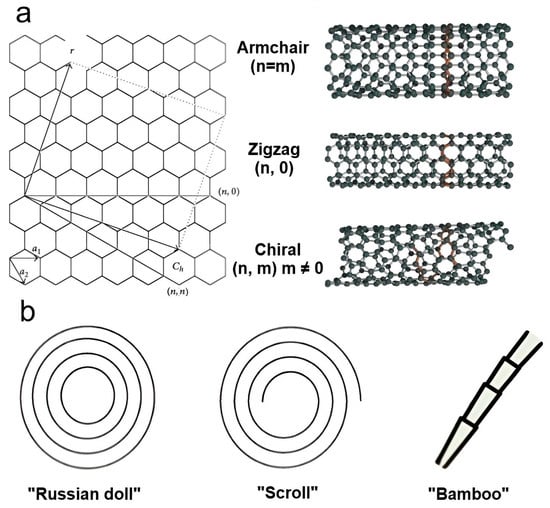

CNTs are a type of carbon allotrope, which were discovered by Iijima [

74]. These 1D, nanoscale, hollow cylinders are formed by rolling up a hexagonal lattice of sp

2-hybridized carbon atoms without any seams [

75,

76,

77,

78].

CNTs measure a few microns in length and have a nanosized outer diameter, resulting in a large aspect ratio. Depending on the number of rolled-up graphene layers, they can be categorized as single-walled (SWCNTs) (outer diameter ~1–2 nm) and multiwalled (MWCNTs) (outer diameter ~2–50 nm), with interlayer spacing in the range of 0.32–0.35 nm [

75,

79]. There are three main nanotube configurations for SWCNTs depending on the chirality vector (

Ch), i.e., the direction along which the graphene sheet is rolled up: armchair, zigzag, and chiral (

Figure 3a). It is the chirality that predetermines the electrical, mechanical, optical, and other properties of CNTs [

75]. Therefore, SWCNTs can exhibit both metallic and semiconductor conductivity depending on chirality, whereas MWCNTs only exhibit metallic conductivity. MWCNTs are able to take on different shapes, including a Russian doll made of several concentric graphene tubes, a scroll-type structure created by wrapping a single graphene sheet, and a bamboo-shaped structure (

Figure 3b) [

80,

81]. Significantly, the multilayered structure of MWCNTs enables the outer layer not only to protect the inner tubes from chemical reactions during environmental interactions but also to manifest superior tensile properties, which was a disadvantage of SWCNTs [

80]. CNTs can be obtained by using the following different methods: arc discharge, laser ablation, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), plasma-enhanced CVD, liquid pyrolysis, solid-state pyrolysis, flame pyrolysis, bottom-up organic approach, etc. [

80,

82,

83].

Figure 3. The main types of carbon nanotubes: (a) variants of SWCNTs constructed from a graphene sheet along the chiral vector Ch and (b) various forms of MWCNTs.

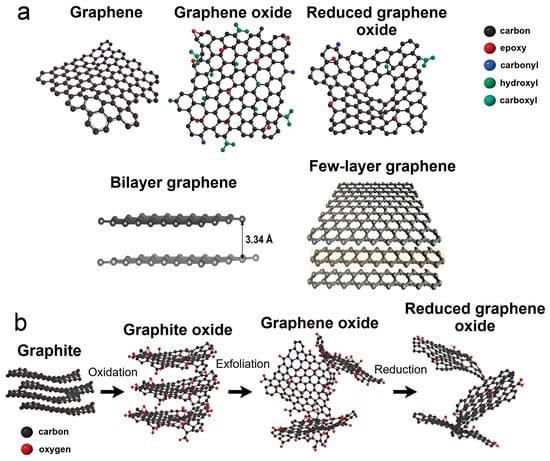

Graphene is a 2D allotrope of carbon, first discovered by Geim and Novoselov in 2004 [

84]. It is a single layer of carbon atoms linked by sp

2 hybridized bonds to form a hexagonal two-dimensional crystal lattice (

Figure 4a). There are also bilayer graphene and few-layer graphene, which are formed from multiple graphene sheets held together by strong π-π interactions (

Figure 4a) [

85,

86,

87,

88]. The complexity of the actual structure of graphene sheets is much more complex due to the presence of edge regions [

88]. They are intricate chemical compounds consisting mainly of oxygen-containing functional groups, such as carboxylates, carbonyls, hydroxyl, epoxy, alkoxy groups, etc. (

Figure 4a) [

89,

90]. The presence of these groups on the edges of graphene function as attachment sites for active particles, polymers, and biomolecules during the formation of composites [

91,

92,

93].

Figure 4. Possible types of graphene and representation of the process of obtaining reduced graphene oxide by oxidative exfoliation of graphite. (a) Types of graphene and the main oxygen-containing functional groups on its edges; (b) Scheme for obtaining reduced GO from graphite by chemical treatment.

Additionally, when preparing graphene-based composites, point and extended structural defects arise in the hexagonal graphene lattice, leading to a significant increase in the number of attachment sites for active particles [

94,

95]. Graphene can be obtained through various procedures including epitaxy; CVD; physical exfoliation of graphite; chemical treatment of graphite to form graphene oxide (GO) through oxidative exfoliation of graphite followed by reduction of GO to form reduced GO (rGO) (

Figure 4b); and others. Each of the aforementioned methods offers a unique level of control over the structure and purity of the obtained graphene, enabling its use in specific areas of science and technology [

91,

96]. Due to their distinctive structure, both CNTs and graphene are two nanomaterials with significant values of optical, thermal, mechanical, and electronic properties. For this reason, they are widely used in the development of new functional composites with improved properties [

97,

98,

99].

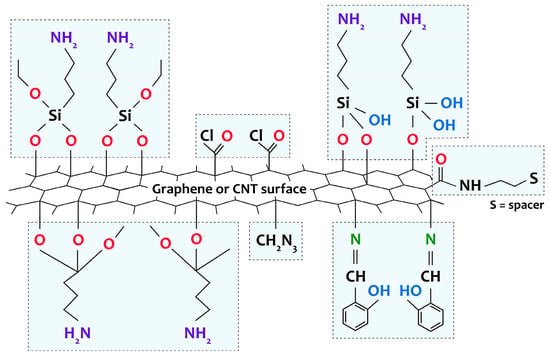

2.2. Features of the Formation of [M(Salen)]/Carbon Nanotubes and [M(Salen)]/Graphene Composites

Currently, preparing composites based on [M(Salen)] complexes and CNTs or graphene remains a challenging and unsolved problem. This is primarily attributed to the ultrasmooth surfaces of both CNTs and graphene, which exhibit few broken bonds or structural defects, with the exception of the edges of graphene or the tips of nanotubes [

97,

98]. Without pretreatment (functionalization), CNT or graphene surfaces tend to bind easily due to strong van der Waals interactions between individual nanostructures, resulting in the formation of poorly dispersed bundles or agglomerates. As a result, poor interfacial interaction between the components of the composite is observed, which seriously impairs its characteristics. To solve this problem, there are methods based on noncovalent (due to electrostatic interactions or physical adsorption) and covalent functionalization (with the formation of stable chemical bonds) of the CNT or graphene surface. Noncovalent functionalization techniques can improve the dispersion quality of carbon nanomaterials in solution. However, they do not address the challenges of interphase interactions at composite interfaces. Covalent functionalization is a more sought-after way of forming composites and is usually obtained by direct reaction of the metal complex with the surface groups of the carbon material or by a spacer (a chain of atoms linking a functional group on the surface of the carbon material and the metal complex) pregrafted onto the carbon material or onto the [M(Salen)] complex (

Figure 5) [

57].

Figure 5. Representation of various groups covalently grafted to the surface of CNTs and graphene by amino-functionalization, chlorination, through spacer attachment, or through direct reaction of the ligand with the surface groups of the carbon support.

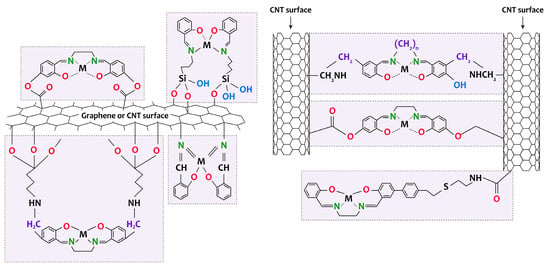

For example, the composites [Mn(Salen)]/MWCNTs [

100] and [Co(Salen)]/SWCNTs [

101] were formed by mixing and reacting both components under ultrasonic conditions without pretreatment of MWCNTs. These composites were then used as a coating for a glass–carbon electrode. In [

102,

103], a [Ni(Salen)]/MWCNTs composite was prepared by first treating MWCNTs with HNO

3 followed by SOCl

2 and then mixing the complex with functionalized MWCNTs in CHCl

3 (

Figure 6). This material has been used to oxidize primary and secondary alcohols and phenol. In other studies [

104,

105], [M(Salen)]/MWCNTs (M = Cu, Ni, Co) composites were synthesized via amino-functionalized with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) or ammonium benzoate. A comparable technique was employed for synthesizing amino-functionalized graphene oxide and preparing [M(Salen)]/GO (M = Mn, Cu, Co, Fe and VO) composites (

Figure 6) [

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112]. The preparing composites underwent testing in conditions of catalytic epoxidation of styrene and unfunctionalized olefins as well as lignin oxidation [

106,

107,

108].

Figure 6. Schematic representation of the formation of [M(Salen)]/carbon nanotubes and [M(Salen)]/graphene composites.

The literature provides several key methods for forming composites of MWCNTs (SWCNTs), graphene, and electrically conductive polymers based on [Ni(Salen)] complexes by electrochemical deposition. One approach is to prepare a conductive electrode with a carbon layer that serves as a substrate for the formation of a polymer, such as poly-[Ni(Salen)] [

5,

7,

42,

113,

114], poly-[Ni(CH

3-Salen)] [

8,

114], poly-[Ni(Salphen)] [

8,

42], poly-[Ni(CH

3-Salphen)] [

8], or poly-[Ni(Saldmp)] [

42], by using a solution consisting of an electrolyte and a monomer and applying potentiodynamic, conventional, or pulsed potentiostatic methods. In the studies referred to, it was mainly MWCNTs that were used as the carbon material, with the preparing composites serving as materials for energy storage. However, this method of composite preparation leads to polymer growth primarily on the outer surface of the carbon nanomaterial, which ultimately restricts the access of the electrolyte to a significant portion of the pores. This restriction leads to a decrease in conductivity at the “carbon nanomaterial-metal salen” interfaces, resulting in a deterioration of the electrochemical properties [

61]. To overcome this limitation, a technique of carbon nanomaterial presoaking in a metal–salen monomer’s highly concentrated solution is utilized to adsorb the complex both on the surface and in the volume of the pores. This technique was first applied to composites of poly-[Ni(Saltmen)]/porous carbon, poly-[Ni(Salen)]/porous carbon, poly-[Ni(3-CH

3O-Salen)]/porous carbon [

47,

115], and subsequently to composites of poly-[Ni(CH

3-Salen)]/SWCNTs [

6] and poly-[Ni(Salen)]/MWCNTs [

116]. The prepared material can then be transferred to a low concentration monomer solution or a solution without monomers for electrochemical polymerization. At the adsorption step, the degree of pore filling in the carbon nanomaterial can be regulated. Afterwards, it can be dried for long-term storage without the loss of the monomeric metal–salen component. An alternative method involves codepositing polymer and carbon material from a mixture of a monomer solution in an electrolyte and a suspension of carbon material, followed by the formation of a composite coating on a conductive electrode [

58]. Poly-[Ni(Salen)]/MWCNTs [

9], poly-[Ni(3-CH

3O-Salen)]/graphene [

114], and poly-[Ni(3-CH

3O-Salen)]/N-FLG (nitrogen-doped few-layer graphene) [

37] composite films were synthesized using this method. However, this approach has a number of disadvantages associated both with obtaining a uniform dispersion of carbon nanomaterials and with the reproducibility of the structure and, accordingly, the characteristics of the composite.

In conclusion, it is important to note that to prepare poly-[M(Salen)]/SWCNTs (or MWCNTs) and poly-[M(Salen)]/graphene composites with a uniformly distributed polymer layer on the carbon material surface and pores, as well as high interfacial adhesion at the “polymer-carbon material” interfaces, predeposition of carbon material on the conducting electrode, additional functionalization of the surface of the carbon material, and subsequent soaking in a concentrated monomer solution are required steps. As a result, synergistic effects of the two phases may occur, leading to an improvement in a number of properties of the composite and the creation of new functionality.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/app14031178