At atmospheric oxygen pressure, the oxidation of aqueous ferrous iron to ferric iron and the precipitation of the latter occur at substantial rates in the absence of living matter. We know this as rust formation. At consequently reduced dissolved oxygen concentrations in groundwater, the rate of these abiotic processes is reduced proportionally however. The accompanying paper (Hassan and Westerhoff (2024) reviews much of the thermodynamics and systems chemistry before turning to the roles that living organisms play. In the environment, microorganisms (i.e., bacteria, archaea or fungi) catalyze these processes, which strongly increases their rates and extents. Some microorganisms can harvest (Gibbs) energy from the oxidation of ferrous iron, which means that they have energy to grow. Provided that other elements required for their growth (like nitrogen and phosphorous) are present, these microorganisms can amplify to high abundance so that the iron oxidation at reduced oxygen levels again becomes substantial until the oxygen activity becomes really low. Other microorganisms can similarly oxidize arsenite to arsenate, reduce arsenate back to arsenite, reduce ferric iron to ferrous iron, or alter ambient redox potential (oxygen concentration) and pH in processes that are all very slow in the absence of microorganisms. Thus, arsenic and iron chemistry in natural waters is not determined just by iron and arsenic chemistry itself but also to a considerable extent by the microbial activities that occur and develop in those waters, i.e., by the Biology.

Conversely, the abundance of the microorganisms depends on the availability of the various forms of iron and arsenic, first as sources of Gibbs energy (e.g., through the oxidation of ferrous iron or arsenic by molecular oxygen catalyzed by these organisms) for their growth and, second, in terms of the toxicity of arsenite and arsenate, which causes death or growth inhibition. Precipitated ferric oxides and associated arsenic species may further enable microorganisms to attach and profit from a stable source of these materials or from the possibility to deposit toxic compounds outside their cells onto such material.

2.1. Organic Matter

The co-occurrence of very high concentrations of dissolved organic matter (DOM) with elevated concentrations of dissolved arsenic and iron in 'reductive' groundwater has often been observed [

99]. DOM significantly influences arsenic biogeochemistry, and

reactive organic matter facilitates the microbial release of arsenic from sediment to groundwater [

57]. Sedimentary organic matter may provide carbon sources for microorganisms. Moreover, shallow groundwater is usually recharged by surface water, importing reactive organic carbon and accelerating microbial processes. Autotrophic microbial growth (i.e. growth that uses inorganic CO

2 from the atmosphere to synthesize its organic carbon) may further increase the organic matter density. Such changes in the organic matter potentially influence both the spatial and the temporal evolution of groundwater arsenic geochemistry.

2.2. Microbiology of Arsenic: What Can Microorganisms Do?

Microorganisms cannot perform miracles. What they do must be consistent with thermodynamics, i.e., the processes that they catalyze must run downhill in terms of Gibbs energy. They can, however, escape from this limitation by coupling a thermodynamically uphill reaction to a different, thermodynamically downhill reaction. The most important example is the coupling of the often thermodynamically uphill reaction of microbial growth [

100] to a process delivering Gibbs energy. The latter process is photon absorption in photoautotrophic microorganisms (which use light absorption for their input energy), the catabolism of organic material in heterotrophs, and inorganic reactions such as arsenite or ferrous iron oxidation by oxygen or nitrate in lithoautotrophs. This example is most important because microbial growth leads to the autoamplification of the chemical activities. The catalyst of the process, i.e., the microorganism, can thereby become tremendously active. Limitations here are the time it takes for the microbes to replicate and the other chemicals they require for growth. The elements carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous, and sulfur are minimally required, and this is an important issue as some ecosystems are lacking in one or more of these and, in other ecosystems, competing microorganisms strongly reduce their levels. It is an important observation that the elements and Gibbs energies may be limiting, but not the catalytic activities; the microbial geosphere is rich and dispersed enough to catalyze virtually anything that is possible in terms of thermodynamics and element conservation. And it will augment itself through proliferation.

Accordingly, microbial communities drive much of the global biogeochemical cycling of arsenic, and they do this through diverse metabolic functions [

31,

101,

102]. In addition to Gibbs energy harvesting and coupling, microorganisms have evolved a variety of mechanisms to overcome the effect of metal(loid) toxicity. These include (i) mechanisms that restrict arsenic entry into the cell or enable active extrusion, (ii) enzymatic detoxification through redox transformations, and (iii) chelation or precipitation [

103,

104,

105]. Frequently metal(loid) resistance genes are located on mobile genetic elements and are readily transferred between different bacteria via horizontal gene transfer [

106]. Taxonomically diverse bacterial populations

viz.

Alpha-,

Beta-,

Gamma-

proteobacteria,

Firmicutes (

Bacillus and relatives),

Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, etc., play roles in the bio-geochemistry of arsenic-rich groundwater [

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114]. Chemolithotrophic and heterotrophic arsenic-transforming bacteria deploy an array of metabolic routes in arsenic speciation, distribution, and cycling in aquatic systems [

101,

115,

116,

117]. Diverse microbial genes encode metabolic processes involved in arsenic-oxidation, -reduction, and -methylation [

118,

119,

120,

121] and thereby affect arsenic speciation, mobilization, and availability as well as ecotoxicity [

122,

123]. Levels of mobile arsenic in groundwater depend on the balance between all the biochemical processes mentioned. These therefore need to be evaluated in any particular case of arsenic contamination in groundwater.

Microorganisms contribute to arsenic removal, in particular, ferrous iron oxidizers and arsenite oxidizers. We here come with examples.

2.3. Microbial Oxidation of Ferrous Iron

Ferrous iron [Fe(II)] is an electron donor to a wide range of iron-oxidizing bacteria, and such iron oxidation can be operated at both acidic and neutral extracellular pHs, under either oxic or anoxic conditions (

Figure 2). Fortin et al. noted that microbial iron oxidation is accelerated through a variety of mechanisms [

124]. At pH = 4, the apparent negative midpoint potential of the oxygen–water couple amounts to −

E0′ = −1.0 V, i.e., 0.23 V lower than that of the ferrous/aqueous ferric iron couple (−

E0′ = −0.77). This implies that respiration with molecular oxygen as an electron acceptor, ferrous iron as an electron donor, and aqueous (i.e., soluble) ferric iron as a product is thermodynamically feasible in environments with an acidic pH, i.e., for

acidophilic organisms; precipitation into goethite or hematite is not required for these energetics. Thus, ferrous iron constitutes a good source of Gibbs free energy for aerobic

acidophilic prokaryotes [

125,

126].

Acidithiobacillus spp., (

β-Proteobacteria) are by far the most studied group of bacteria capable of gaining Gibbs energy from the oxidation of ferrous to ferric iron at a very low pH.

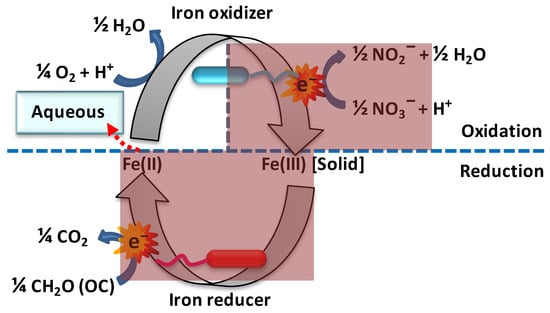

Figure 2. Microbial redox cycling of iron. In microaerophilic conditions, chemolithoautotrophic bacteria use Fe(II) as a source of electrons and couple the reduction of nitrate (or oxygen) to the oxidation of Fe(II) to Fe(III), which then precipitates (Fe(III)[solid] is equivalent to ferrihydrite precipitates such as hematite and goethite). In the bottom half of the cycle, heterotrophic Fe(III)-reducing bacteria couple the reduction of Fe(III) to the oxidation of organic carbon (OC), whereupon Fe(II) is released to the water as Fe2+(aq). The overall reaction is the oxidation of organic carbon by nitrate or oxygen to carbon dioxide and water, nitrite or nitric oxides, and even nitrogen, which yields Gibbs energy in the form of ATP, which drives the biosynthesis and replication of the microbes. The shaded dark red areas indicate the absence of oxygen.

This explains the first of the four physiological groups of bacteria that oxidize ferrous iron, i.e., (i) acidophilic, aerobic iron oxidizers; (ii) anaerobic, photosynthetic iron oxidizers [

74]; (iii) neutrophilic, microaerophilic iron oxidizers; and (iv) neutrophilic, anaerobic (nitrate-dependent) iron oxidizers.

Fully anaerobic ferrous iron oxidation is conducted by anoxygenic, phototrophic, purple, non-sulfur bacteria utilizing ferrous iron as a reductant for thermodynamically uphill carbon dioxide fixation, with light as a Gibbs energy source [

127]. It is clear where the photosynthetic iron oxidizers get their Gibbs energy from, but how can we understand the energetics of the two remaining groups?

The aerobic oxidation of ferrous iron by neutrophilic microorganisms (

Figure 2) may seem paradoxical as at pH = 7 the midpoint potentials of the ferrous/ferric iron couple and the oxygen–water couple are too close to allow for Gibbs energy to emerge in the process. However, the precipitation of the ferric iron as ferrihydrites such as goethite and hematite reduces the effective electron potential (−

E0′) to (−

E0′ = 0.2 V at pH = 7, much lower than the electron potential −

E0′ = 0.8 V of the oxygen–water couple, so that the oxidation of ferrous iron by oxygen can still occur. Microaerophilic conditions are required because only then can aerobic, ferrous iron-oxidizing bacteria compete effectively with the abiotic oxidation of ferrous iron by oxygen that would dominate at atmospheric oxygen tensions [

128]. Neutrophilic, microaerophilic conditions are indeed common where iron-rich waters meet an oxic-anoxic interface due to low mixing rates and the limited molecular diffusion of oxygen in water [

129]. Microaerophilic, iron-oxidizing bacteria thrive in wetland soils, plant rhizospheres [

130,

131], places where iron seeps into groundwater supplying freshwater [

132,

133], and drinking water distribution systems [

134]. Chemolithoautotrophic bacteria (e.g.,

Gallionella spp. and

Sideroxydans spp.) extract their metabolic energy from iron oxidation under these conditions [

135,

136,

137], but this is not the case for obligate heterotrophs such as the

Sphaerotilus-Leptothrix groups [

138]. Among the four recognized species of

Leptothrix,

L. ochracea is the only species for which there is circumstantial evidence of autotrophic growth using Gibbs energy derived from iron oxidation [

74]. Aerobic, chemolithotrophic, magnetite-oxidizing bacteria may contribute significantly to ferrous iron oxidation at a circumneutral pH [

129,

132,

133,

136,

139,

140]. Currently, all known oxygen-dependent, neutrophilic, chemolithotrophic iron oxidizers belong to the

Proteobacteria group, with

Gallionella as the best known representative [

137], belonging to the

β-

proteobacteria group

. Gallionella sp. can also grow on organic compounds such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose [

141], and sulfur (electron potential −

E0′ = 0.06 V) or sulfide (−

E0′ = 0.10 V) [

142,

143] may serve as better electron donors compared to the ferrous iron in cases where ferrihydrite precipitation is slow or problematic.

A signature of iron-oxidizing bacteria is the unique morphological structures they produce, such as sheaths (in heterotrophic species) and helical, stalk-like filaments (in autotrophic species, although autotrophic

Siderooxydans spp. form neither sheaths nor stalks [

74]). Excreted from the cell surface, the stalk of

Gallionella acts as an organic matrix for the deposition of the ferrihydrites produced (e.g., as hematite Fe

2O

3) [

144]. In view of the thermodynamic importance of Fe(II) oxidation to ferrihydrite (see above), these unique structures are essential for the energetics. Moreover, arsenate may be trapped by Fe(III) that binds to the stalk or other extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) on the surface of bacteria to form As(III)-Fe(III)-EPS complexes [

145,

146], or just by Fe(III) in magnetite.

Twisted stalks of

Gallionella ferruginea may further act as a protective mechanism against precipitated ferric iron or oxygen toxicity [

147]. The metals may also bind as cations to the cell surface in a passive process [

124], perhaps with tighter binding of the triply charged ferric iron, thereby again increasing the iron’s electron (negative redox) potential −

E0′. Many neutrophilic, iron-oxidizing bacteria can form ferric iron minerals that can co-precipitate with arsenic [

148]. Also, heterotrophic

Leptothrix strains are able to deposit iron oxyhydroxides onto their cell surface [

149].

The biological oxidation of ferrous iron in the absence of oxygen and in dark subsurface waters is also possible by light-independent chemoautotrophic microbial activity using nitrate as the electron acceptor [

150] (

Figure 2). Indeed, nitrate-reducing, iron-oxidizing bacteria are the most important catalysts for the generation of ferric oxides under anaerobic conditions [

128]. Nitrate-dependent, iron-oxidizing microorganisms are able to oxidize both soluble and insoluble ferrous iron minerals [

151]. For the thermodynamic reasons given above, the ferric iron must occur in complexes (such as with hydroxide in ferrihydrite/magnetite): nitrate/nitrite −

E0′ = −0.41 V at pH = 7 and −

E0′ = −0.60 at pH = 4 are both too high in electron potential for reduction by free ferrous iron transiting to free ferric iron (−

E0′ = −0.77). Even

Escherichia coli is capable of nitrate-dependent iron oxidation [

152].

In a further demonstration of how interactions between various inanimate and animate processes may accomplish processes that are otherwise thermodynamically impossible, there are at least three further solutions to the small Gibbs energy yield of iron respiration with nitrate as electron acceptor. One is the use of complexed ferrous iron as a substrate:

Thiobacillus denitrificans oxidizes ferrous sulfide (FeS; electron potential at pH 7 of approximately −

E0′ = −0.25 V, i.e., higher than the −

E0′ = −0.42 V of the nitrate/nitrite couple. This nitrate-dependent iron sulfide oxidation has been demonstrated for the hyperthermophilic archaeon

Ferroglobus placidus [

153], the mesophilic

Proteobacteria Chromobacterium violacens [

154], and the

Paracoccus ferrooxidans strain BDN-1 [

155]. A further alternative is the nitrate reduction (−

E0′ = −0.42 V) or chlorate reduction (−

E0′ = −0.79 V) [

156] coupled to ferrous iron oxidation in the presence of carbon and a Gibbs energy source, This has been documented for the heterotrophic

Dechlorosoma suillum strain PS [

157] as well as for the

Acidovorax strain BoFeN1 [

158].

2.4. Microbial Oxidation of Arsenite

- Oxygen as an electron acceptor

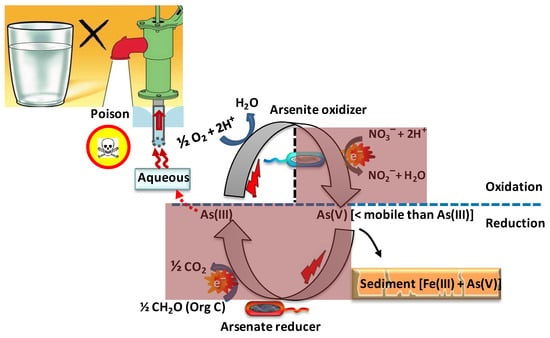

The biological oxidation of arsenite (

Figure 3) is an attractive alternative to its rather slow abiotic oxidation due to its potential specificity for arsenite, efficiency, effectiveness at lower oxygen tensions (through a low

KMfor oxygen), and cost effectiveness in addition to environmental friendliness [

165]. In environments where significant amounts of arsenite are oxidized to arsenate within a short period of time, this oxidation can be attributed to arsenite-oxidizing bacteria [

166].

Figure 3. Scheme of putative microbial arsenic cycling in aquifers and consequences for drinking water. Microbial arsenite oxidation (above the dashed line) is mediated by a number of chemolithoautotrophs, under aerobic conditions at the surface or anaerobic conditions below that surface, using oxygen or nitrate, respectively, as the terminal electron acceptor. Microbial arsenate reduction (below the dashed line) is mediated by dissimilatory, arsenate-respiring bacteria coupling arsenate reduction under anaerobic conditions to the oxidation of organic carbon, the resulting arsenite entering into aqueous solution. The shaded dark red areas indicate the absence of oxygen.

Despite or perhaps precisely because of its biochemical toxicity (see above), arsenite is readily converted by a diversity of prokaryotes. Arsenite-oxidizing bacteria are classified into heterotrophic (HAO) and chemolithoautotrophic (CAO) arsenic oxidizers [

120,

167]. Heterotrophic arsenite oxidation may serve primarily as a detoxification reaction, rather than as a Gibbs energy source (in heterotrophs, other catabolic reactions readily provide the Gibbs energy required for growth): it converts arsenite encountered in the cell’s periplasmic space into the less toxic arsenate, perhaps making it less likely for the arsenic to enter the cell [

101].

More than 50 phylogenetically diverse, arsenite-oxidizing (auto- and heterotrophic) species, distributed over 25 genera, have been isolated from various environments, especially mesophilic ecosystems [

169]. Green, for instance, reported arsenite-oxidizing bacteria stemming from cattle dipping baths [

170] and Battaglia-Brunet et al. isolated a

Leptothrix sp. strain S1.1 from the settling pond sediments of mine drainage that was able to oxidize 0.1 g/L of As(III) in 1 week at 12 °C [

171]. Phylogenetically, arsenite oxidizers are dispersed within the

Alpha-,

Beta-, and

Gamma-proteobacteria;

Actinobacteria;

Firmicutes; and

Deinococcus-Thermus. Green sulfur bacteria (e.g.,

Chlorobium limnicola and

Chlorobium phaeobacteroides) and filamentous green non-sulfur bacteria (e.g.,

Chloroflexus aurantiacus) may also be capable of arsenite oxidation, as homologs of the gene-encoding arsenite oxidase (see below) have been identified in their genomes [

60,

172,

173,

174,

175]. The most extensively studied heterotrophic arsenite oxidizer is

Alcaligenes fecalis [

120]. Little is known regarding the role of archaea in the oxidation of arsenite.

Heterotrophic

Alcaligens faecalis [

176] and

Pseudomonas pudia [

177] have not been shown to extract Gibbs energy from the oxidation of arsenite during heterotrophic growth. There is one known exception:

Hydrogenophaga sp. str. NT-14, a β-

proteobacterium, can oxidize arsenite whilst it grows heterotrophically, its arsenite oxidation still being coupled to the reduction of oxygen and yielding extra Gibbs energy for growth [

121]. Gihring and Banfield (2001) isolated a peculiar thermophilic species of

Thermus (strain HR 13) from an arsenic-rich hot spring. Under aerobic conditions, it was able to oxidize arsenite apparently for detoxification purposes, i.e., without conserving Gibbs energy. However, under anaerobic conditions, strain HR 13 can grow on lactate using arsenate as its electron acceptor, reducing it to arsenite [

178].

Arsenite oxidase, located on the outer surface of the inner bacterial membrane, has been identified in both autotrophic and heterotrophic bacteria [

101,

120]. The enzyme is the first component of an electron transport chain that enables arsenite to reduce oxygen to water in a process coupled to proton pumping and the subsequent generation of ATP from ADP and phosphate. The genes encoding arsenite oxidase (

aio genes) show considerable divergence; the

aioA sequences of CAOs are phylogenetically distinct from those of HAOs [

169,

179]. Only two putative arsenite oxidase genes have been identified in

Aeropyrum pernix and

Sulfolobus tokodaii by sequence homology searches in their published genomes [

180].

- Alternative electron acceptors

Molecular oxygen is poorly soluble in water (up to some 0.25 mM only, and also the rate at which it dissolves is small whenever the surface-to-volume ratio is small). Aerobic microbes in the upper oxic layers of aquifers consume dissolved oxygen, maintaining anaerobic zones below them. Anaerobic or facultative anaerobic microbes thereby become dominant in the underlying anoxic environment [

181]. Alternative oxidants (e.g., nitrate; −

E0′ = −0.42 V) then have the potential to support growth through the microbial oxidation of arsenite −

E0′ = −0.06 V. Several studies have indeed demonstrated that anaerobic microorganisms can engage in nitrate-dependent arsenite oxidation to gain Gibbs energy [

167,

182]. Such arsenite-oxidizing, denitrifying bacteria have been isolated from various environments and enriched [

53,

167,

183,

184]. As their electron potential is also far below that of the arsenite/arsenate couple, besides nitrate also chlorate (ClO

3−; −

E0′ = −0.79 V) [

185] can be an oxidant (electron acceptor) for the anaerobic microbial oxidation of arsenite.

Dechloromonas sp. strain ECC1-pb1 and

Azospira sp. strain ECC1-pb2 constitute examples [

182].

Most arsenite-oxidizing, denitrifying organisms are

Alpha,

Beta, or

Gamma-proteobacteria. The first identified anoxic, arsenite-oxidizing bacterium was

Alkalilimnicola ehrlichii strain MLHE-1, a haloalkaliphilic facultative chemolithoautotroph: it is also able to grow heterotrophically with acetate (−

E0′ = 0.29 V for CO

2/acetate couple; [

71]) as its electron donor, either aerobically, or anaerobically with nitrate as an electron acceptor. A novel type of arsenite oxidase gene (

arxA) was identified in the genome of this extremophile, which fills a phylogenetic gap between the arsenate reductase (

arrA) and arsenite oxidase (

aioA) clades of arsenic-metabolizing enzymes [

186]. Anoxic, chemolithoautotrophic, arsenite-oxidizing strains DAO1 and DAO10 (closely related to

Sinorhizobium and

Azoarcus sp., respectively) living under “normal” environmental conditions are also able to oxidize arsenite to arsenate with complete denitrification of nitrate (see above for the energetics) [

53].

3. Perspectives

After these examples of roles played by microbes in the determination of arsenic levels in groundwater, we jump to the much needed perspective on how to remediate this toxicity. Aspects of the arsenic toxicity of groundwater have been the subject of a great many, often excellent, reviews already. These reviews focused on one (or a number of closely related) aspects of the topic. Ganie et al. (2023) [282], for instance, focused on arsenic toxicity in the human. Dilpazeer et al. (2023) discussed arsenic management strategies and the feasibility, cost effectiveness, merits and demerits of the different types of arsenic removal technologies in depth [283]. Also in 2023 Patel et al. discussed the many routes of exposure of the human to arsenic as well as worldwide contamination [20]. Cerron-Calle et al. (2023) discussed electrified technologies for removing arsenic from drinking water [284]. Hassan et al. (2023) focused on the array of arsenic-removing techniques [48]. Fatoki et al. (2022) paid most attention to the environmental toxicity of arsenic and discussed the interaction of arsenic iron sulfide and its toxicity to mammals [68]. Monteiro de Oliviera et al. (2021) discussed the pathologies arising from arsenic toxicity [285], whilst Sing et al. (2021) focused on the spatial distribution of arsenic contamination in an aquifer in central India [286]. Shaji et al. (2021) considered the entire Indian peninsula whilst focusing on public health, human toxicity, and policies [19]. Uppal et al. (2019) only gave a brief overview of the situation in various countries, particularly in Southeast Asia [287]. Likewise, Ahmad and Bhattacharya (2019) [288], Yunus et al. (2016), and Sing and Stern (2017) presented brief but interesting overviews and alerts [289,290]. The book by Hassan et al. (2018), Arsenic in Groundwater Poisoning and Risk Assessment, has many chapters, which are mainly on toxicology and public health, with little about microbiology, arsenic and iron chemistry, or on the integration of all these aspects [291]. Bhowmick et al. (2018) had an interesting focus on biomarkers of arsenic toxicity [292].

All these aspects are important for the arsenic toxicity of groundwater and all these reviews are well-worth studying, therefore. In our most recent review (Hassan and Westerhoff, 2024), we have shown, however, that arsenic toxicity is not determined by the mere sum of all the effects discussed in these previous recent reviews: the various effects amplify and/or ameliorate each other through interactions often depending on external conditions such as pH, redox potential, and the presence of substances accelerating microbial growth. It is in highlighting these cross-influences that the present review adds to the already existing ones: we have focused on how arsenic toxicity is the net effect of a substantial number of processes that interact nonlinearly. This nonlinearity of the interactions between the processes make analysis and outcome prediction complex and, indeed, we have discussed how the outcome of existing attempts at subsurface arsenic removal (SAR) have been disappointing. Examples of these nonlinearities were the co-precipitation of arsenate with ferric iron as well as the effect of the oxidation of ferric iron on the oxygen tension and thereby on the density of aerobic microorganisms playing key roles in oxidizing arsenite or ferrous iron. The ability of microbes to enhance their density greatly when they can extract Gibbs energy for growth from their environment, constituted an example. This may relate to the organisms’ use of arsenite or ferrous iron as electron donors or to their consumption of arsenate or ferric iron as electron acceptors when organic chemicals in the environment allow for heterotrophic growth. The oxygenation and reinjection of groundwater thereby has complex effects on arsenic mobility: whether it oxidizes the arsenite and immobilizes it as arsenate depends on whether sufficient ferrous iron is oxidized to ferric iron oxide and precipitates as such. The presence of various microbial species, as evidenceable by pangenomic analyses (i.e. the sequencing of all genomes and transcriptomes in a water sample), may enhance the oxidation of ferrous iron considerably, but may also remobilize arsenic by the reduction of the arsenate or ferric iron once the oxygen has been consumed. It is high time for a systems approach to heavy metal contamination of groundwater, with arsenic as a first example.

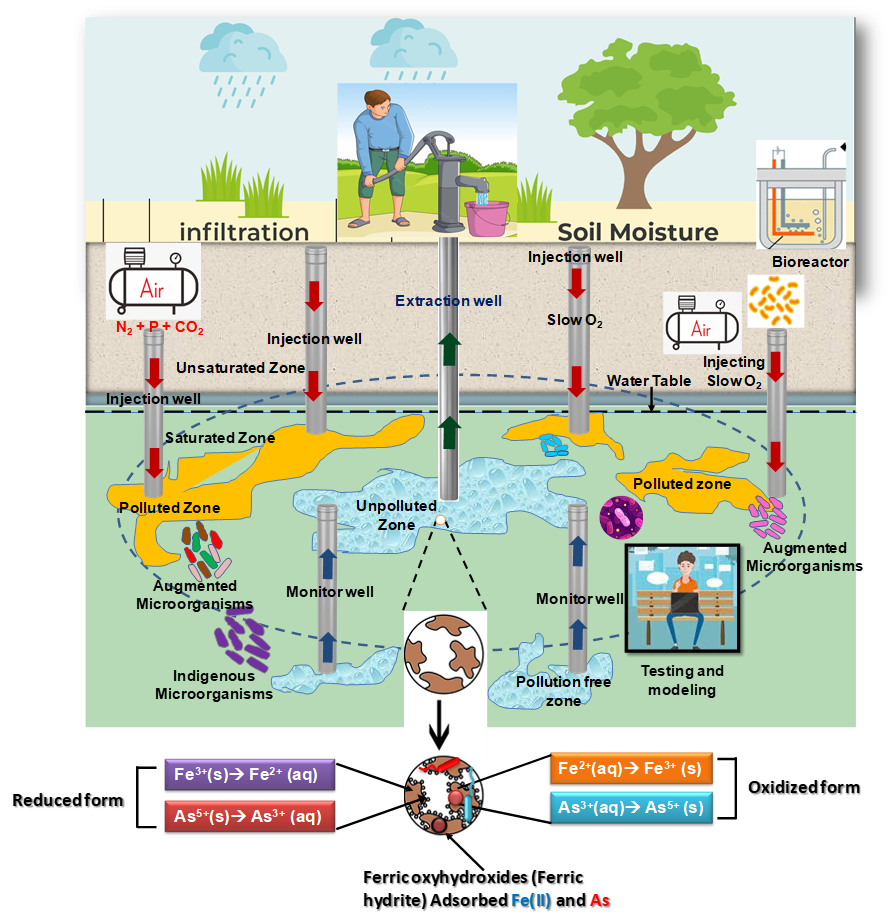

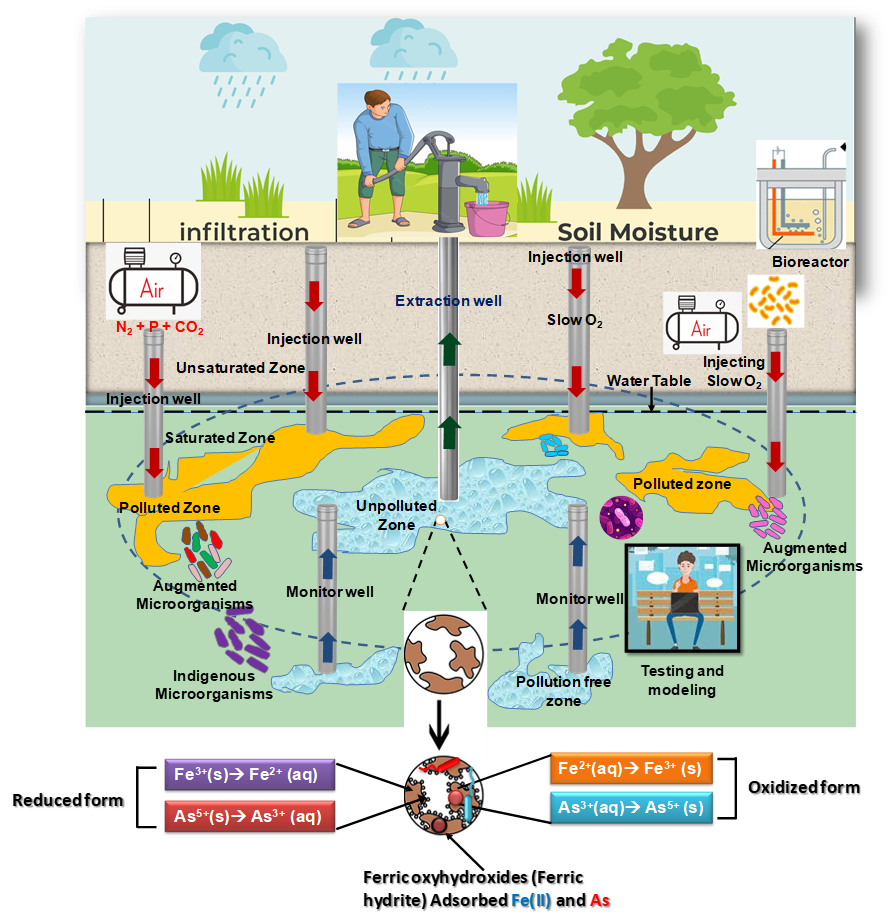

Figure 4. Proposed model of bSAR using engineered microorganisms for up-scaling the bioremediation of arsenic through bioaugmentation. Distinct extraction and injection wells (proposed fluid flow indicated by arrows) are used in combination in order to integrate the control of the flow of contaminated groundwater with above-ground bioreactor treatment and the subsequent reinjection of nutrient-spiked effluent. Injection wells are sunk at the periphery of the contaminated site and O2 is sparged periodically, but at a slower than diurnal rhythm and at a slower rate or lower partial pressure. Monitoring wells are used to identify the contamination level, the activity of microorganisms, and the sufficient amount of nutrients available for microbial growth. At some point, if indigenous microbial load or number is reduced due to perturbation, then injection of engineered microorganisms into the subsurface would be a good option in order to augment the bioremediation process with local inhabiting microbes. Once the bSAR model has been optimized, arsenic pollution-free waters can be abstracted through the extraction well for drinking and other purposes. Combination with physical chemical methods of treating water

The qualitative state and dynamics of nonlinear systems such as the one that determines arsenic in groundwater, depends on the values of their parameters, and one of the perspectives that this review offers is that of detailed experimental analyses (see Figure 4) of multiple and different sites of arsenic pollution. A second perspective is that of system-wide collection of multiple data sets, such as pangenomic analyses of the metabolic and growth capabilities of all microbial species present at a site. A third perspective is that of including the measurement of important thermodynamic parameters such as pH and ambient redox potential (and dissolved oxygen concentrations) and an assessment of their effects on the relative abundance of the various forms of arsenic and iron. We have illustrated this in the equilibrium thermodynamic sense but, ultimately, time-dependent measurements will be necessary, as some processes appear to be slow. When processes and their cross-connections are nonlinear, it becomes impossible to understand and predict the behavior of a system by intuition or interpolation/extrapolation. One therefore needs to invoke the assistance of mathematical modeling and chemical and biological theory, which is our fourth perspective.

The modeling of the nonlinear interactions determining the arsenic toxicity of groundwater is still in its infancy. A pessimist might even suggest that any aim towards an integral understanding of the arsenic toxicity of groundwater is too ambitious. We are more optimistic for a number of reasons: (i) the genomics revolution has dramatically enhanced the ability to determine the microbial population of a groundwater site, (ii) the proteomics and metabolomics revolutions will soon enable a further identification at the level of proteins and metabolites, (iii) progress in bioinformatics and systems biology of single species has recently extended to ecosystems as well as to flux predictions therein, and (iv) the software and capabilities of mathematical modeling have also increased sharply. Our fifth, more integral, perspective, therefore, is the development of a systems biology/chemistry of the arsenic toxicity of groundwater.