Endometriosis has a prevalence of 10% worldwide in premenopausal women. Probably, endometriosis begins early in the life of young girls, and it is commonly diagnosed later in life. The prevalence of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) in adolescence is currently unknown due to diagnostic limits and underestimation of clinical symptoms. Dysmenorrhea is a common symptom in adolescents affected by DIE, often accompanied by dyspareunia and chronic acyclic pelvic pain. Ultrasonography—either performed transabdominal, transvaginal or transrectal—should be considered the first-line imaging technique despite the potential for missed diagnosis due to early-stage disease. Magnetic resonance imaging should be preferred in the case of virgo patients or when ultrasonographic exam is not accepted. Diagnostic laparoscopy is deemed acceptable in the case of suspected DIE not responding to conventional hormonal therapy. An early medical and/or surgical treatment may reduce disease progression with an immediate improvement in quality of life and fertility, but at the same time, painful symptoms may persist or even recur due to the surgery itself.

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disease characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity. The prevalence is 10% in premenopausal women. Probably, endometriosis starts early in the life of young girls but is commonly diagnosed later in life [

1].

Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is the most aggressive type of endometriosis, with deep infiltration of tissues leading to subverted anatomy and functionality of vital organs and reduced quality of life [

2]. Its prevalence in adolescent age is currently unknown due to the underestimation of clinical symptoms and unsolved diagnostic challenges.

Among clinical symptoms, dysmenorrhea is widely experienced in adolescents affected by endometriosis [

3]. Dysmenorrhea may be primary or secondary, and the distinction between the two forms is essential for clinicians.

Endometriosis is the leading cause of secondary dysmenorrhea in adolescents and may be associated with other typical symptoms, including chronic pelvic pain (CPP), dyspareunia, heavy menstrual bleeding and infertility [

4]. According to the ESHRE guidelines [

5], manifestations suggestive of endometriosis include early menarche, severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, abnormal uterine bleeding (heavy or irregular bleeding), mid-cycle or acyclic pain, resistance to empiric medical treatment (such as painkillers and hormonal therapy) and gastrointestinal and genitourinary symptoms. Furthermore, the disease may present atypically with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as constipation, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and, less frequently, urinary symptoms [

6].

Despite the presence of severe painful symptoms, the diagnosis of endometriosis in young patients is challenging. Most often, adolescents are affected by early-stage endometriosis. In these cases, physical examination or instrumental diagnostic imaging may fail to detect the small-sized endometriotic foci [

8]. Hence, endometriosis is more commonly diagnosed late after the age of 25, seven to nine years after symptoms’ onset [

9].

Although some authors affirm DIE lesions do not grow after the age of 25 [

10], some others suggest that endometriosis could be a progressive disease with early onset of DIE [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Regardless of who is right, early diagnosis and early treatment may prevent or at least slow down disease progression and have a good impact on both quality of life and fertility. Indeed, patients with advanced stages of disease who undergo surgery have an increased risk of intra- and post-operative complications [

15] and may show symptoms persistence due to surgery itself, particularly in the presence of posterior DIE and, less frequently, in the case of anterior DIE [

16,

17].

2. Pathogenesis of DIE in Adolescents

The pathogenesis of DIE is unclear, with several hypotheses, theories and even speculations [

18]. The absence of animal models mimicking human endometrium functions and simulating the potential specific growth mechanisms of DIE feeds the debate. There is even more uncertainty on the pathogenesis of DIE in adolescents. It is probably caused by the same combination of factors postulated for adults, with some slight differences that promote adolescent DIE [

19].

Neonatal menstruation may explain some forms of endometriosis in adolescence [

20,

21]. In most girls, the functional transition to fully responsive endometrial cells is achieved during adolescence. In about 5% of neonates, newborns’ endometrium can be sensitive to pregnancy’s high maternal progesterone levels, and menstrual shedding can occur early in the first week of life. In these neonates, retrograde menstruation occurs because of the relatively long cervix and thick cervical secretions [

13]. Retrograde endometrial cells contain stem cells along with perivascular mesenchymal stem/stromal cells together with niche cells, which implant in the peritoneal mesothelium, leading to a very early and inactive stage of disease.

Indeed, some prenatal factors may also be associated with the onset of DIE in adolescence, such as preeclampsia and low birth weight [

21]. The underlying mechanism would be the fetal hypoxic environment caused by placental insufficiency that would increase endometrial sensitivity to progesterone [

23] and the altered platelet activation leading to augmented angiogenesis [

13]. It is hypothesized that the presence of a fetal hormonal milieu then facilitates the development of DIE [

24].

However, endometriosis in prepubertal girls is very rare, and neonatal menstruation [

20] alone cannot explain the progression from a “very early-stage” disease (i.e., endometrial attachment to the mesothelium) to DIE disease [

25]. The quiescent and early-implanted endometrial cells are probably reactivated by increasing ovarian activity during menarche and thelarche with the growth of endometriosis lesions [

18,

20,

26]. Surrounding smooth muscle hyperplasia may play a role in this process by supporting endometrial glands and stroma to dive deep into fibromuscular tissues [

25,

27]. The implantation would be encouraged by macromolecular oxidative damage and recurrent tissue injury and repair, with destruction of the peritoneal mesothelium and chronic inflammation due to peritoneal iron excess and local bleeding of ectopic endometriotic lesions [

18,

25].

Nevertheless, the progressive evolution of the disease is debated and, to date, not yet clearly defined [

25].

The metaplasia theory was proposed more than 50 years ago to explain endometriosis development in women without a uterus [

28]. This theory stems from the old histological concept that the histological aspect of a mature cell can transform into that of another mature cell. Metaplasia is considered a consequence of stem cells’ growth activity.

The immunological theory has been proposed to explain the migration of endometriotic cells outside the uterus and their survival in the ectopic environment [

36,

37,

38]. The existence of this pathogenetic mechanism is supported by the high prevalence of autoimmune diseases coexisting with endometriosis, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, hypothyroidism and fibromyalgia.

Evasion of immune surveillance and numerous cytokines implicated in angiogenesis and the activation of proinflammatory pathways play a key role in this process [

39]. Elevated levels of circulating and local cyclooxygenase-2, tumor necrosis factor-α, prostaglandin-E2, growth factors, cytokines and angiogenic factors are implicated in proinflammatory signaling [

40].

3. Prevalence of DIE in Adolescents

Despite the efforts from researchers, the real prevalence of endometriosis in adolescence is, so far, an unsolved enigma. The estimates vary widely, with ranges between 19% and 100% [

63,

64], reflecting the uncertainty about this aspect of adolescent endometriosis.

The estimated prevalence of adolescent DIE is even more uncertain. DIE prevalence changes according to the inclusion criteria of each study’s population (i.e., overall vs. symptomatic adolescents) and the diagnostic employed, which includes imaging, with detection of ultrasonographic or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features suggestive of DIE, and surgery, with direct visualization of the disease [

65]. Collection of medical history, especially regarding painful symptoms associated with DIE, is not diagnostic but may drive towards an early diagnosis [

66,

67,

68,

69].

The same research group later published a retrospective observational study that showed sonographic signs of posterior DIE in 10.6% of adolescent patients who had undergone ultrasonographic exams for severe dysmenorrhea [

71]. Instead, no signs of anterior DIE were detected.

Regarding DIE prevalence on MRI diagnostic, Millischer et al. prospectively investigated the prevalence of DIE and OMA in a series comprising 308 adolescents aged 12–20 years who underwent MRI for severe dysmenorrhea [

72]. In this cohort, MRI was positive for DIE and/or OMA in 39.3% of the cases. In particular, DIE was observed in 88.4% of the cases, with predominantly retrocervical involvement (87.6%) and coexisting OMA in 9.1% of the cases. This study also highlighted the increasing prevalence of overall endometriosis, rising from 16.7% at the age of 12–13 years to 60.5% at 20 years, and revealed no site-specific distribution along with age variations.

4. DIE Symptoms

According to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) guidelines [

5], offering surgery to young women for a histological diagnosis of endometriosis is no longer considered appropriate nowadays. Therefore, imaging exams and the collection of medical history assume a central role in the diagnostic workup towards an early diagnosis of endometriosis. Indeed, several studies suggest the use of a combination of a patient’s clinical history and imaging exams to increase the chance of diagnosis [

70,

71,

76].

Regardless of the methodology employed for diagnosis, adolescents presenting with symptoms suggestive of endometriosis, and hence DIE, should be referred to referral centers to avoid diagnostic delay [

76].

Most patients with endometriosis refer dysmenorrhea in adolescence or at a young age [

77,

78]. According to Di Vasta et al., dysmenorrhea can be the presenting symptom of adolescent endometriosis in over 90% of them [

66]. It starts at menarche in half of adolescent patients, is frequently associated with nausea (69.5%) with no vomiting (75%) and is described as severe in 63% of the cases [

66]. The distinction between primary (menstrual pain with an organic disease) and secondary dysmenorrhea (menstrual pain without an organic disease) should be mandatory when addressing adolescent patients. Indeed, endometriosis represents the main cause of secondary dysmenorrhea in adolescents [

76,

78].

Dysmenorrhea is often neglected, and it is viewed as temporary and natural [

81], despite having a high impact on women’s lives [

82]. Dysmenorrhea should always be investigated, considering the prevalence of endometriosis in adolescents and young women who refer this symptom, especially when it is severe [

71,

72] and tends to remain stable over time [

68]. Education programs have been delivered in some nations with the aim of making adolescent patients aware of the symptomatology associated with endometriosis [

69], enhancing early diagnosis. There is also increasing awareness of the power and amplitude that social media and e-learning may provide in the education of both patients and caregivers [

83].

Dysmenorrhea may also be important due to its correlation with specific disease locations, being more frequently associated with posterior DIE and adenomyosis rather than ovarian endometrioma [

85]. However, this association has not been investigated in adolescent patients, and further studies are needed to assess the relationship between the DIE site and the specificity of symptoms [

38].

Other suggestive symptoms, such as dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain (CPP) or abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), may accompany dysmenorrhea, and the coexistence of these symptoms increases the possibility that endometriosis is present [

71,

76,

86].

Chronic acyclic pelvic pain is more likely to occur in adolescents rather than adults [

87,

88,

89,

90]. It is strictly related to endometriosis when it is severe and drug-resistant [

75,

89] but luckily seems to have a decrease in intensity over the years [

68] despite starting with higher intensity in younger patients [

90]. Severe chronic acyclic pelvic pain may reflect central sensitization, leading to treatment failure and association with other different painful diseases [

68,

91,

92]. When chronic pelvic pain is reported, many other gynecologic (i.e., fibroids, adenomyosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian mass, hematocolpo) and non-gynecologic organic disorders should be excluded.

Among pelvic painful symptoms, dyspareunia can be associated with DIE and a more severe disease in adolescents [

93]. However, much like infertility, it is difficult to investigate due to sexual behavior and pregnancy desire rates in these types of patients.

Gastrointestinal and genitourinary symptoms in adolescents can be important indicators of endometriosis, particularly suggesting the presence of posterior DIE and adenomyosis [

5,

71]. Endometriosis can mimic the clinical features of several organic pathologies, including inflammatory bowel diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, Meckel’s diverticulum, celiac disease and sub-acute/chronic appendicitis [

94,

95,

96,

97], imposing a multidisciplinary approach to exclude gastrointestinal diseases.

5. The Role of Imaging in Adolescence DIE Diagnosis

According to the literature, endometriosis in adolescents who underwent surgery is more frequently an early-stage disease, according to the rASRM classification [

71,

75,

89,

99]. Additionally, endometriomas are more common in adult women compared to adolescents [

88,

100]. Therefore, there is a concrete possibility of overlooking stage I/II deep infiltrating endometriosis among adolescents by using imaging diagnostics that may not be able to detect direct signs of the disease.

MRI or US seem to provide similar accuracy in excluding ovarian or deep endometriosis localizations but have not been validated yet in studies investigating an adolescent population [

101,

102,

103]. However, considering that both MRI and US show high accuracy in detecting endometriosis in young patients, the preferred diagnostic approach in adolescents should be ultrasonographic [

76,

104]. US holds several advantages as compared to MRI in terms of lower costs and wider availability, both for the patients and for the caregivers.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) is preferred in the case of sexually active adolescent patients with suspected endometriosis. However, transrectal sonography (TRS) can be offered in virgin puberal patients, with similar diagnostic accuracy to the TVS technique [

70,

76,

105]. The role of TRS in the evaluation of posterior compartment endometriosis in adults has been investigated both by Ohba [

106] and Koga [

107].

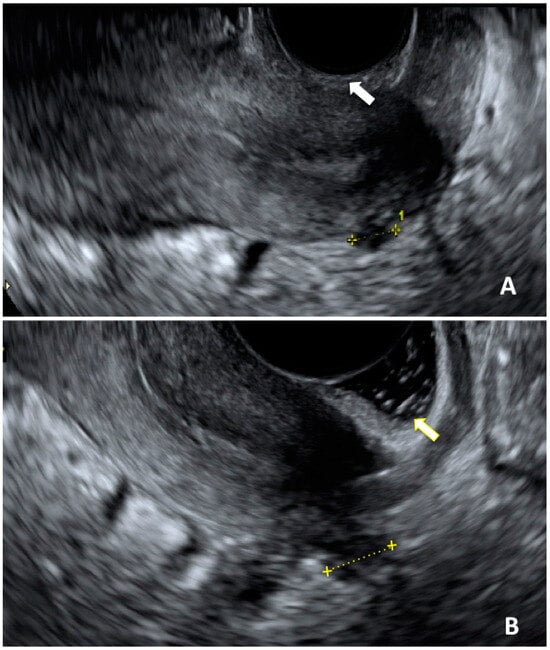

Up to now, US accuracy for adolescent deep infiltrating endometriosis has been poorly investigated. The diagnostic performance of the exam compared to a reference “technique”, such as surgery, is difficult to estimate due to the relatively low percentage of patients undergoing surgery for endometriosis [

14,

71,

89]. In a recently published retrospective study, Martire et al. detected isolated DIE in 3.7% of patients, mostly located at the uterosacral ligaments (

Figure 1) [

70]. The presence of concurrent symptoms was high, especially dysmenorrhea, and this combination enhances the diagnostic performance of US alone [

66,

71,

74,

94].

Figure 1. Ultrasonographic image of a DIE nodule affecting uterosacral ligament. (A): acquisition of DIE nodule length in a sagittal plane without sonovaginography (white arrow); (B): same acquisition performed with sonovaginography (yellow arrow).

Moreover, there are no data on the reproducibility of US for adolescent endometriosis among expert sonographers and gynecologists with different expertise. The literature advocates for experienced operators in order to avoid or shorten diagnostic delays [

111].

Thus, keeping in mind the dark corners of US and its uneven acceptability, further or alternative investigations are advisable in the case of symptomatic adolescents [

8,

89] with no clear diagnosis or when a US exam is not applicable nor accepted. In these cases, MRI may be a valuable option [

112,

113,

114].

6. Adenomyosis and DIE in Adolescence

Adenomyosis is a chronic disease involving the myometrium characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial and stromal tissue. It is linked with a spectrum of painful symptoms, such as dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia and pelvic pain, and clinical signs, such as heavy menstrual bleeding and infertility [

117].

The prevalence of adenomyosis among women is yet to be defined: the data based on histological evaluation of hysterectomy samples report ranges between 15 and 55% [

118].

Adenomyosis can affect adolescent patients with varying prevalence ranging from 5% to 17.4% [

72,

119,

120], often in a mild to moderate form with potential clinical implications [

120,

121]. It is usually diagnosed with noninvasive exams, including ultrasound and MRI [

72,

120,

121]. Adenomyosis may reveal itself in diffuse or focal forms, such as myometrial cysts or adenomyomas [

122].

While it may be a rare condition, in the presence of painful pelvic symptoms or heavy menstrual bleeding in an adolescent patient, it should be thoroughly excluded, particularly when coexisting with DIE [

120].

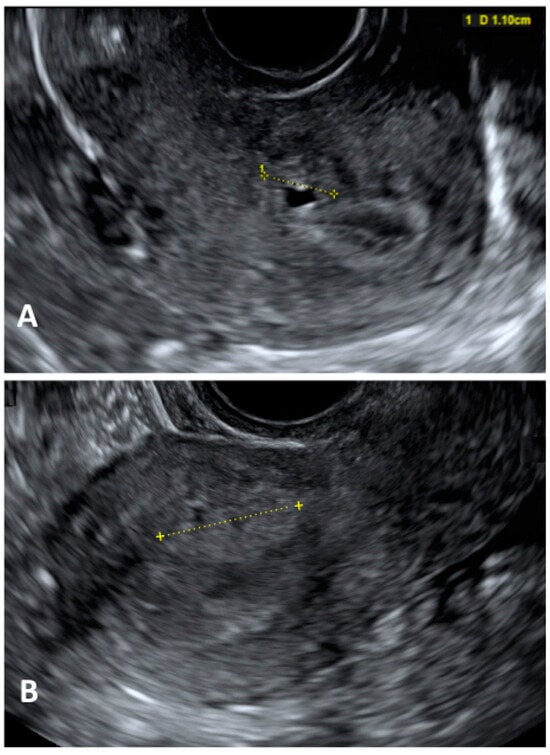

Diagnostic laparoscopy should not be employed as the first diagnostic assessment in this group of patients because it may lead to overtreatment and unnecessary invasive procedures (

Figure 2). US should be the first-line imaging exam despite the potential overlapping US characteristics with fibroids in patients undergoing hormone therapy [

123].

Figure 2. Ultrasonographic image of a focal adenomyosis. (

A): measurement of a myometrial anechoic cyst; (

B): measurement of a hyperechoic myometryal island.

7. Management

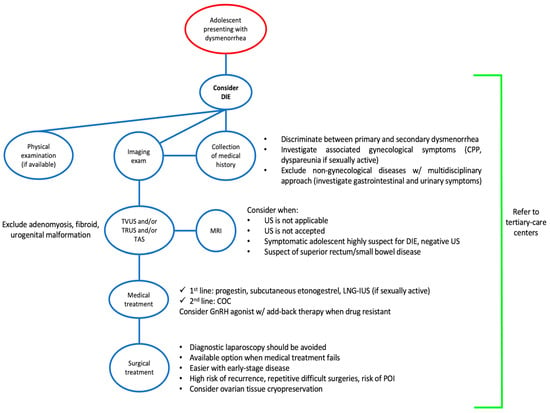

The treatment of DIE in adolescents should be aimed at reducing painful symptoms, suppressing or controlling the progression of the disease and safeguarding future fertility [

126] (

Figure 3).

Figure 3. Flowchart for the management of deep infiltrating endometriosis in adolescents. Abbreviations: COC, combined oral contraceptive; CPP, chronic pelvic pain; DIE, deep infiltrating endometriosis; GnRH, gonadotropin releasing hormone; LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; TAS, transabdominal ultrasound; TRUS, transrectal ultrasound; TVUS, transvaginal ultrasound; US, ultrasound; w/, with.

8. Conclusions

The diagnosis of DIE in adolescent patients is particularly challenging and can be easily overlooked.

DIE should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of adolescents presenting with painful symptoms, especially secondary dysmenorrhea. Adenomyosis may coexist with DIE; therefore, clinicians should carefully evaluate these patients and choose the most adequate therapeutic approach.

A timely diagnosis is crucial and can be achieved with a combination of medical history, physical examination, ultrasound and/or MRI. Indeed, DIE is more frequently encountered at an early stage; hence, imaging exams alone may fail to detect small lesions. Referral to a tertiary care center is advisable to allow the best management of such a complex, debilitating and chronic disease. Dedicated specialists should provide information on the long-term management and need for follow-up of DIE that starts in adolescence.

Appropriate treatment includes progestins as a first-line option, followed by combined oral contraceptives and GnRH analogues in selected cases. When medical treatments fail to improve the quality of life or reduce the progression of disease, surgery should be employed, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation might be considered.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm13020550