1. The Differentiation of Diseases Causing Dysphagia

Formulating differential diagnoses for swallowing disorders involves distinguishing among various conditions that can lead to impaired swallowing function. Dysphagia is categorized into organic swallowing disorders (static dysphagia) and functional swallowing disorders (dynamic dysphagia). Organic dysphagia results from structural abnormalities such as tumor lesions or inflammatory conditions extending from the oral cavity to the esophagus. It can also manifest as mechanical impediments to bolus passage due to irregularities in the passage or compression from the surrounding tissues. In contrast, functional dysphagia is characterized by normal anatomy but abnormal bolus transport function from the oral cavity to the esophagus. Other potential causes include eating disorders and psychiatric conditions [

3,

4]. Neurological disorders mainly present with functional dysphagia [

7,

8,

9]. A comprehensive assessment of the patient’s symptoms and clinical findings is essential to accurately diagnose the underlying cause of dysphagia.

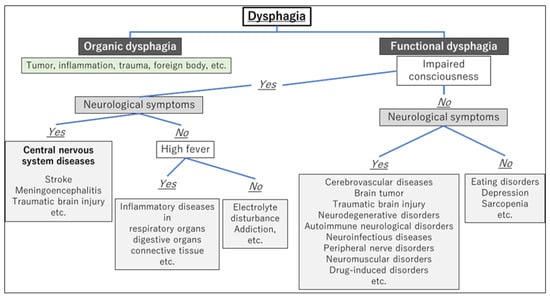

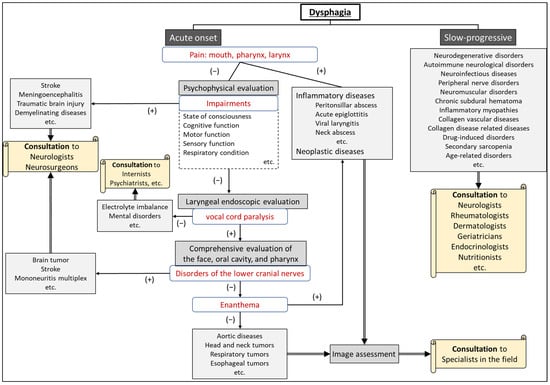

After differentiating whether dysphagia is organic or functional, a flowchart for evaluating the underlying cause of dysphagia, based on the presence of consciousness disorders, is illustrated in Figure 1. A flowchart for differentiating the causative disease of dysphagia according to whether the course of dysphagia is acute in onset or slowly progressive is shown in Figure 2. In patient assessments, it is essential to prioritize a comprehensive interview, encompassing the current and past medical history, family background, medication usage, and other pertinent details, before proceeding to a meticulous evaluation of the oral and pharyngeal regions. Thorough psychosomatic assessments are highly important.

Figure 1. Flowchart for evaluating the underlying cause of dysphagia based on the presence of consciousness disorders.

Figure 2. Flowchart for differentiating the etiology of dysphagia according to whether the onset is acute or slow-progressive.

2. Neurodegenerative Disorders Causing Dysphagia

2.1. Representative Neurodegenerative Disorders Causing Dysphagia

Major neurodegenerative disorders (NDDs) that cause dysphagia include Parkinson’s disease (PD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), multiple system atrophy (MSA), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and Huntington’s disease, and so on.

2.2. Parkinson’s Disease

PD is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by symptoms such as resting tremor, muscle rigidity, and bradykinesia. More than 80% of patients with Parkinson’s disease develop dysphagia during the course of the disease; however, the degree of dysphagia does not necessarily correlate with the severity of PD [

10]. In PD, all voluntary and involuntary motor processes in swallowing can be impaired: cognitive stage impairment due to depression and cognitive dysfunction [

9], preparatory and oral stage impairment due to tremor and rigidity, pharyngeal stage impairment due to delayed swallowing reflex, decreased pharyngeal contractility, laryngeal elevation impairment [

1,

11], esophageal stage impairment due to upper esophageal sphincter (UES) dysfunction, and esophageal peristalsis impairment [

12]. Furthermore, it should be noted that dysphagia can occur as a side effect of therapeutic medications in patients with PD [

13]. Bilateral vocal fold movement disorders may also occur in patients with PD [

14,

15]. Tracheostomy, laser arytenoidectomy, or aspiration prevention surgery may be performed for progressive airway narrowing and severe dysphagia [

14,

15,

16].

2.3. Multiple System Atrophy

MSA is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a combination of autonomic failure plus cerebellar syndrome and/or parkinsonism. MSA is categorized into two main subtypes: MSA-parkinsonian type (MSA-P), which is more like PD, and MSA-cerebellar type (MSA-C), which is associated with balance and coordination problems [

17]. Dysphagia is a frequent and disabling symptom of MSA that occurs within five years [

17,

18]. Abnormalities in the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing, along with esophageal dysfunction and aspiration, occur in MSA and worsen as the disease progresses [

17,

19,

20]. Bilateral vocal fold movement impairment (abduction disorder) occurs more frequently in MSA than in PD [

21] and is characterized by an exacerbation of vocal cord dysfunction during sleep [

22]. Depending on the progression of MSA, procedures such as tracheostomy or aspiration prevention surgery may be necessary [

16,

23].

2.4. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive NDD. ALS affects the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. It specifically targets motor neurons, which are the nerve cells responsible for controlling muscle movements, including those used in talking, chewing, swallowing, and breathing [

24]. Dysphagia is a significant and progressive symptom in ALS [

25]. Dysphagia in ALS correlates significantly with bulbar onset and oral and pharyngeal swallowing impairment [

25,

26], while the esophageal phase is relatively preserved at the early stage of the disease [

27]. Dysphagia contributes to malnutrition, dehydration, and aspiration pneumonia and accounts for a significant proportion of deaths in patients with ALS [

25]. Early intervention and comprehensive management of dysphagia are crucial for addressing the risk of aspiration and its impact on the well-being of patients with ALS [

28], and preventing aspiration is a critical aspect of managing ALS-related dysphagia [

29]. Tracheostomy or aspiration prevention surgery may be performed because of respiratory deterioration or progression of dysphagia [

16,

29,

30].

3. The Evaluation of Patients with Suspected Neurodegenerative Disorders

3.1. Patients with Neurodegenerative Disorders among New Outpatient Visits

In outpatient visits, some patients presenting with dysphagia or dysarthria as a chief complaint may have a background of NDDs. Patient data over approximately a decade (beginning in 2013) at the University of Tokyo Hospital showed that among 7910 patients attending the voice and swallowing clinic, 4973 (62.9%) had dysphagia, vocal fold movement disorder, or dysarthria. Of these, 1044 (13.2%) had already been diagnosed with NDDs (unpublished data). Among 3929 patients (49.7%) without a diagnosed underlying condition during the initial outpatient visits, 37 (1.0%) had suspected NDDs during otolaryngological examinations. Following referral to a neurologist, 19 patients (0.5%) were diagnosed with NDDs. This means that NDDs are hidden in the background of a small number of patients who present with dysphagia as their chief complaint.

3.2. Physical Signs and Oro-pharyngo-laryngeal Findings Suggesting Neurodegenerative Disorders

When the following findings are observed during medical interviews and physical assessments, it is recommended to proceed with the examination with consideration for NDDs:

When the following findings are observed upon examination of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx, the possibility of neurodegenerative disorders should be considered in conjunction with other physical examination findings:

-

Dysarthria;

-

Speech impairment (hoarseness, low volume);

-

Tongue atrophy and limited tongue movement;

-

Velopharyngeal insufficiency (during articulation and/or swallowing);

-

Vocal fold movement impairment;

-

Reduced pharyngeal contraction;

-

Decreased pharyngo-laryngeal sensation.

Dysarthria can be confirmed not only through pronunciation assessments, such as “/pa//ta//ka/,” “/ra//na/,” and “/ŋa//ŋa/,” but also through the repetition of tongue twisters when evaluating [

37]. Tongue atrophy, tremors, and motor dysfunction are characteristic features observed in a variety of neuromuscular disorders [

38]. Notably, tongue atrophy frequently manifests in conditions like ALS with bulbar involvement, muscular dystrophy, and severe myasthenia gravis. Tongue tremor is observed in conditions such as PD, essential tremor, and MSA-P [

39,

40]. When assessing tongue motor dysfunction, a finding of the mandible moving with the tongue is a compensatory maneuver for tongue motor impairment. Velopharyngeal insufficiency should be assessed during both swallowing and vocalization (/ka/, /ŋa/). Velopharyngeal insufficiency may be present during swallowing, even when open nasal speech is not present (velopharyngeal closure is possible during speech), and vice versa. ALS should be suspected when there is a discrepancy between velopharyngeal closure during swallowing and speech [

41]. Velopharyngeal insufficiency can also occur in multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, myasthenia gravis, muscular dystrophy, etc [

42]. Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) has been reported in various neurological disorders, including PD and MSA, and rarely in ALS and Guillain-Barre syndrome [

43,

44]. Reduced pharyngeal contraction and decreased pharyngolaryngeal sensation are commonly associated with a range of NDDs. In ALS, sensory disturbances are generally not evident until the disease has significantly advanced.

4. The Management of Dysphagia in Neurodegenerative Disorders

4.1. Meal-Time Management

Managing dysphagia in patients with NDDs involves providing support and guidance tailored to their current condition. Despite the frequent progressive nature of these disorders, there is the possibility of temporary improvement through pharmacological treatment, particularly in PD. Therefore, addressing swallowing difficulties in accordance with a patient’s specific conditions is advisable. Depending on the degree of the patient’s functional impairment, nutritional and swallowing guidance should include specific instructions regarding the following components: [

45,

46,

47,

48]

For individuals with dysphagia, adjusting the physical properties of the diet according to swallowing function is important to lessen the risk of choking and subsequent aspiration pneumonia [

49]. Increasing the bolus thickness has been identified as a means of lowering the risk of airway penetration. However, these adjustments in the physical characteristics of the bolus are associated with reduced palatability and an increase in pharyngeal residue, potentially amplifying the risk of post-swallow aspiration [

50].

The modification of bolus size is a critical consideration in dysphagia management and should be tailored to the specific needs of the individual patient. Medical professionals may increase the bolus size to stimulate a swallow response or decrease it for patients who require multiple swallows per bolus. Larger bolus volumes have been associated with faster pharyngeal transit, while smaller volumes may be safer for swallowing in some populations [

51,

52].

Effectively addressing feeding posture in the context of dysphagia, especially in individuals with neurological impairments, such as those found in ALS, involves specific head and body positioning techniques to optimize the safety and efficiency of the swallowing process. These strategies aim to reduce the risk of aspiration and ensure a satisfactory nutritional intake. [

28,

53,

54]

In addition, guidance should be provided based on the patient’s medical and physical condition, including adjustments to meal settings, thoughtful supervision, posture modifications, and the utilization of self-help devices such as spoons of different sizes and lengths.

4.2. Swallowing Rehabilitation

The establishment of short- and long-term goals for patients undergoing swallowing rehabilitation varies depending on whether the condition is a progressive disease with no established treatment or a disease with available therapeutic approaches. However, the key points in the management of all swallowing disorders are conservative treatment, pharmacotherapy, and rehabilitation (swallowing voice, and speech). Swallowing training includes indirect exercises performed without the use of food, such as ice massages to facilitate the swallowing reflex [

55], head-lift exercises (Shaker exercise) to strengthen laryngeal elevation [

56,

57,

58], respiratory muscle training [

59,

60], and neuromuscular electrical stimulation [

50,

61]. In contrast, swallowing training can also include direct exercises that involve the use of food, such as effortful swallows and multiple swallows. Certain compensatory techniques used during eating are also a very common component of swallowing training, such as the chin-tuck maneuver and head rotation. Optimal intervention entails a multidisciplinary approach, with collaboration among physicians, speech-language pathologists, nurses, dietitians, and other healthcare professionals [

3,

50,

62].

- ▪

-

Indirect exercises

-

Facilitating the swallowing reflex: ice massage [

55]

Ice massage is a technique designed to trigger the swallowing reflex by lightly rubbing and applying pressure to the posterior tongue, tongue base, velum, and posterior pharyngeal wall with an ice stick for 10 s.

- Strengthening laryngeal elevation: resistance-based exercises and head-lift exercises (Shaker exercise) [56,57,58,63]

These exercises aim to strengthen the muscles involved in swallowing, particularly in patients with reduced superior and anterior movements of the hyolaryngeal complex. These include head-lift (Shaker) exercises, Mendelsohn Maneuver, effortful swallowing, and chin-tuck maneuver against resistance. Head-lift (Shaker) exercises involve lying flat on the back and lifting the head to look at the toes while keeping the shoulders down for 60 s and repeating this three times. The second part consists of a repetitive movement: lifting the head to look at the chin, lowering it to the bed, and repeating this 30 times for three sets.

-

Respiratory muscle training [59,60]

This exercise is used to strengthen the muscles of respiration and is weakened by various conditions including ALS, PD, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This can also help improve speaking, swallowing, and coughing, as these functions use the related muscles.

-

Cough reflex exercise [63]

This exercise aims to strengthen the muscles involved in swallowing and enhance airway protection. This results in an improved closure of the larynx and enhanced coordination between swallowing and coughing to prevent aspiration.

-

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation [50,61]

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation is a noninvasive therapy that aims to improve the coordination, endurance, sensory feedback, and timing of the muscles involved in swallowing. This treatment is often used in combination with traditional treatments to improve swallowing.

- ▪

-

Direct exercises

-

Effortful swallow [

64,

65]

This technique aims to recruit more motor units during swallowing, increase muscle demand, and create a muscle-training/strengthening effect. It involves continuously exerting force on the neck while maintaining the larynx in the maximally elevated position during swallowing.

Multiple swallows involves a series of repeated swallows to clear a single bolus from the oropharyngeal cavity. This aims to enhance the ability to modulate the timing, force, and coordination of the multiple muscles involved in swallowing.

This technique involves repeated swallows that alternate between solid foods and liquids as the bolus. This process is repeated several times. The purpose of this approach is to facilitate the movement of food and liquid through the swallowing process, helping to ensure safe and efficient swallowing.

- ▪

-

Compensatory swallowing maneuvers [

67,

68]

This maneuver helps redirect food and liquid from the airway, reducing the risk of aspiration. It entails the individual tucking their chin toward their chest before or during swallowing. This position reduces the space between the tongue base and the back of the throat and increases pharyngeal pressure to facilitate bolus movement.

Head rotation during swallowing can be performed as a compensatory technique for individuals with dysphagia. Studies have shown that head rotation can improve swallowing in patients with unilateral oropharyngeal dysphagia. This maneuver helps redirect food and liquids away from the airway, reducing the risk of aspiration.

-

Supraglottic Swallow [72]

The Supraglottic Swallow is a technique to prevent aspiration during swallowing. It involves the voluntary closing of the vocal folds by holding one’s breath before and during swallowing, followed by an immediate cough after swallowing. The maneuver aims to safeguard against aspiration and clear any post-swallowing residue.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm13010156