Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Plant stress is a significant challenge that affects the development, growth, and productivity of plants and causes an adverse environmental condition that disrupts normal physiological processes and hampers plant survival. Epigenetic regulation is a crucial mechanism for plants to respond and adapt to stress.

- plant stress

- epigenetic regulation

- DNA methylation (DM)

- genome-wide profiling

1. Introduction

Plants are fascinating organisms, with the remarkable ability to modulate their developmental processes and adjust to their surroundings through epigenetic modifications. These modifications extend beyond the realm of genetically encoded factors, adding an extra layer of regulation [1][2]. In the plant kingdom, epigenetic inheritance takes two forms: transferring information not encoded in DNA between generations and preserving epigenetic modifications within an individual reset between generations [3][4]. Comprehending the intricacies and operations that differentiate the two forms of epigenetic inheritance holds great significance. This area of research is particularly fascinating because stress can stimulate stress-signaling pathways which enhance stress gene responses; this knowledge can also be used to develop strategies for improving crop yield, quality, and stress resistance, which are benefiting agriculture and the ecosystem [5][6]. Plants use epigenetic regulation to enhance immunity and variation during pathogen and pest interactions [7][8][9][10][11]. Recent studies of epigenetic mechanisms significantly impact how plants react to non-living factors and well-understood signal transduction mechanisms [5][12].

It should be noted that inherited stress tolerance mechanisms vary among plant species based on genetic makeup, intensity, and stress duration [13]. Mutations in DNA sequences cause trait variations, which plant breeders use to improve plant populations due to alterations in chromatin states [14]. Notably, plants can remember and learn from their experiences, making them highly adaptable to their environments [15][16]. During stress responses, epigenetic modifications are known to significantly ensure the reprogramming and gene expression of the plant’s transcriptome. These changes are mediated by modifications to the chromatin structure, like “DM, histone modifications (HM), and non-coding RNA molecules”. Instead, it involves modifications to the structure of DNA or associated proteins that can influence gene activity [17]. These modifications can be stable and passed on to subsequent generations, allowing plants to transmit stress memories across generations [14].

Recent research has uncovered that identical plants can exhibit DM changes when subjected to varying stressors [2][18][19][20]. Remarkably, apomictic Taraxacum officinale plants exposed to abiotic stress displayed notable differences in DM, regardless of the specific type of stress. These indicate that epigenetic inheritance may be a pivotal factor in plant adaptation, even when genetic diversity among individuals is absent. Stress-induced methylation patterns are influenced by stress type, genotype, tissue, and organism, which affect stress-responsive gene regulation [21][22]. In plants, DM occurs predominantly at cytosine residues in a CG context (CG methylation), but it can also occur in other sequence contexts, such as CHG and CHH (where H is A, C, or T) [23]. DMs and HMs alter gene expression by inhibiting transcription factor binding or modifying DNA accessibility to regulatory proteins [24].

Epigenetic regulations are vital for plant processes such as growth, development, reproduction, and pathogen resistance, as well as improving adaptability to environmental stressors like temperature, salinity, and nutrient scarcity [12][25][26][27][28]. The manipulation of epigenetic processes requires tremendous effort to enhance crop yield, growth, quality, and productivity. These, in turn, contribute to sustainable agriculture, where epigenetic mechanisms regulate critical agronomic traits in crops via DM, histone modifications, and small RNAs that affect gene expression and impact growth, seeding, germination, and fruit development [29]. The impact of these epigenetic mechanisms is felt directly in crop productivity, yields, and quality.

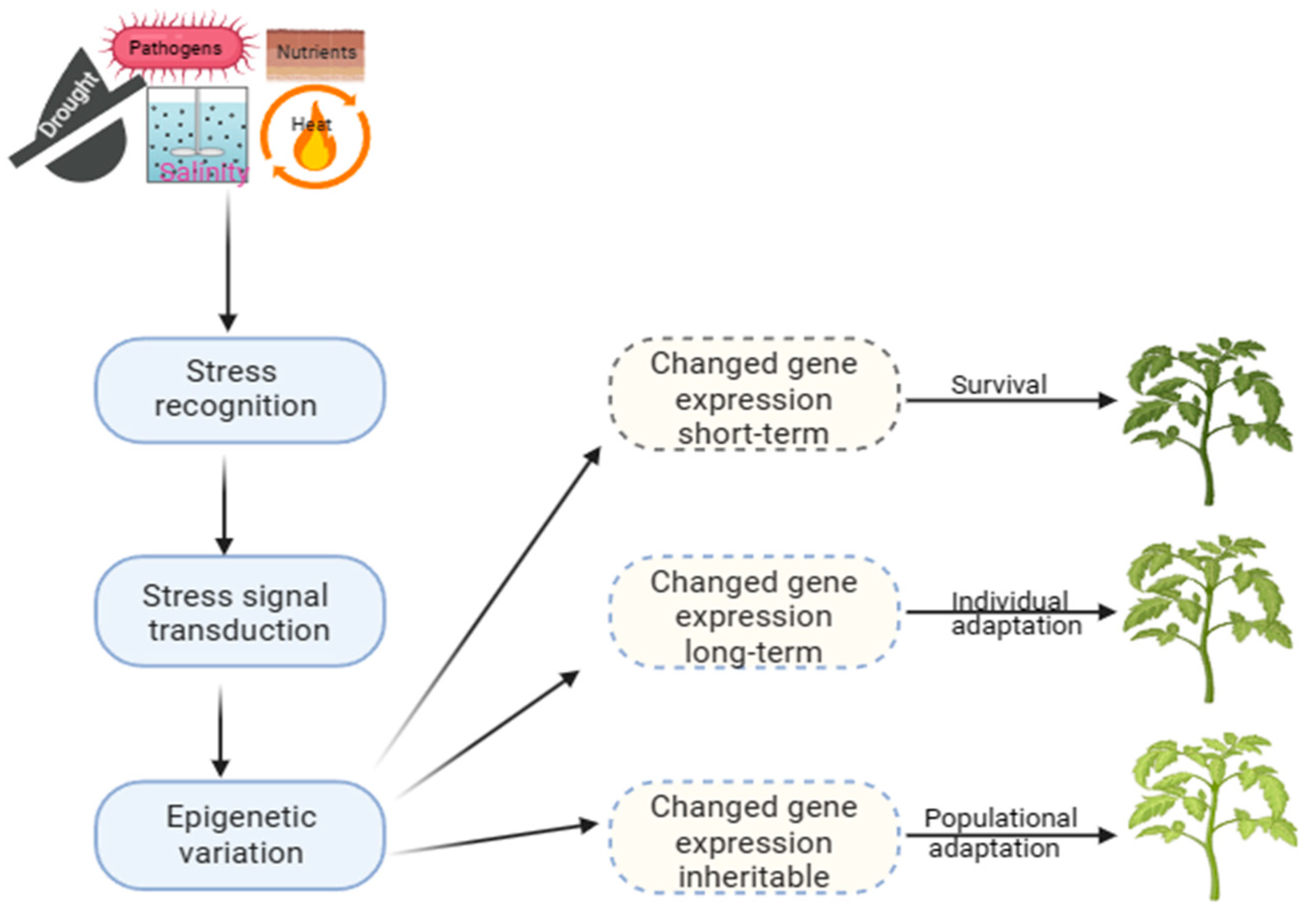

Long-term modifications play a significant role in evolution, providing a stable molecular basis for phenotypic plasticity. At the same time, short-term mechanisms, on the other hand, are crucial for surviving under stress (Figure 1). This adaptation allows the selection of offspring better suited to a constantly changing environment, which can be observed in natural populations with similar genetic makeup, indicating that it is an epigenetic trait [12]. Developing strategies to improve crop productivity under challenging environmental conditions requires a comprehensive understanding of plant epigenetics and stress responses. However, there is still a lack of direct evidence linking epigenetic changes to phenotypic plasticity in plants exposed to varied environments or different types of stress [30]. Recent research has shown that plants can regulate gene expression through DM patterns, which can be altered dynamically under stress to adapt and thrive under harsh conditions [12][31][32].

Figure 1. Epigenetic processes and mechanisms of plant adaptation to stress.

2. Mechanisms of Plant Epigenetic Regulation

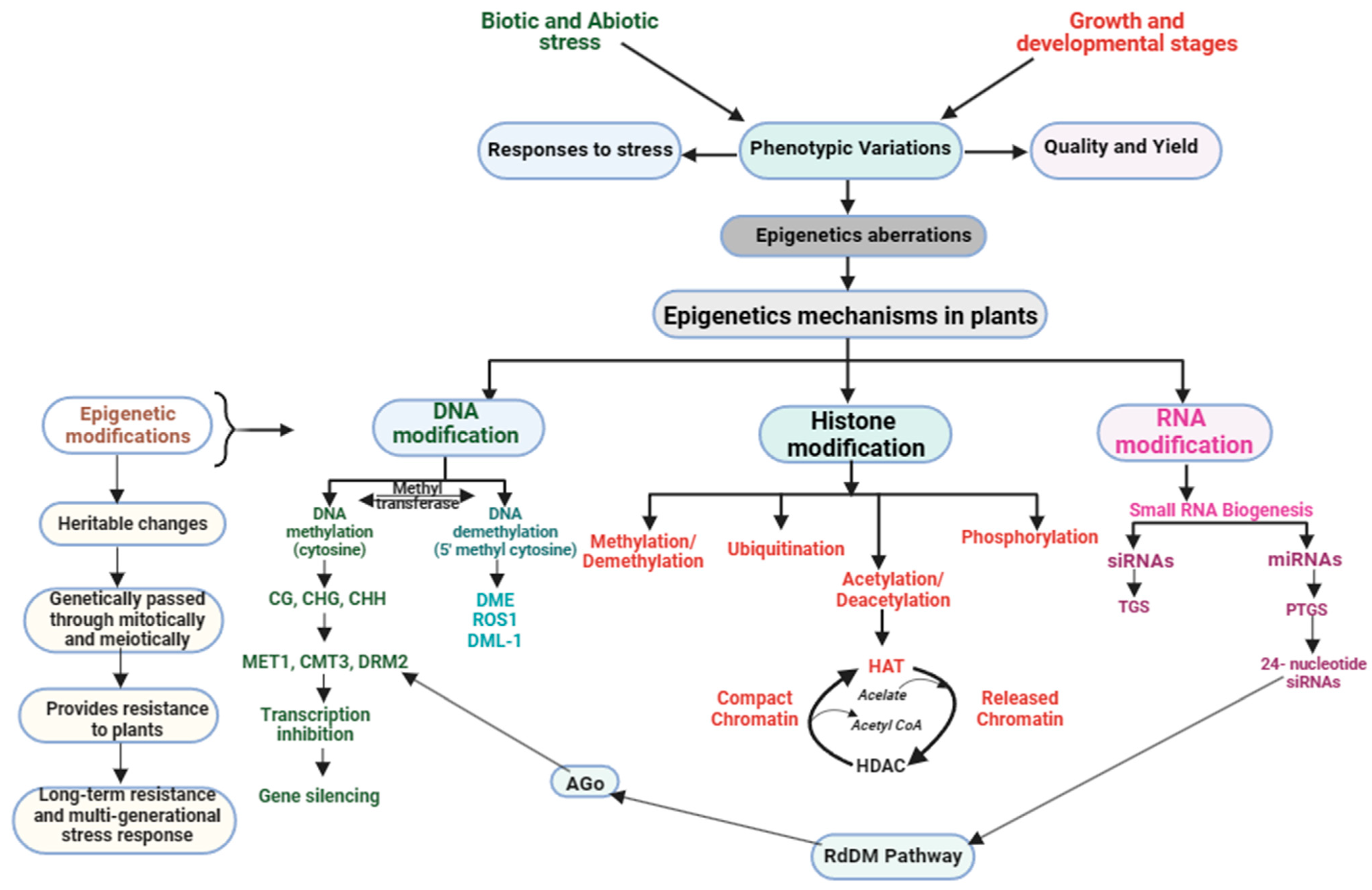

In response to stress, plants employ a range of epigenetic mechanisms to fine-tune gene expression. These tactics comprise DM, histone modifications, small RNA-mediated gene silencing, and chromatin remodeling (Figure 2). Regulating gene expression and maintaining genome stability are crucial functions, with each approach playing a distinct and essential role.

Figure 2. Plant epigenetic modifications in response to stress management during growth and development.

2.1. DNA Methylation (DM)

Epigenetic modification through DM is a well-researched process in the plant kingdom. This process involves adding a methyl group to DNA’s cytosine residues, specifically at CpG dinucleotides. Stress-induced changes in DM patterns can significantly impact gene expression and phenotype plasticity [33]. Recent studies have shown that DM is a dynamic process that responds to various environmental stresses [23][32][34]. It participates in preventing certain transcription factors from binding to DNA and attracting chromatin-modifying proteins [35]. This process also determines histone modification patterns and helps recruit repressor complexes that contain HD7ACs, DNMTs, and MBD proteins. DM, unlike DNA sequence alterations, will result in complex DM states in crossbreeding populations, but it still has the potential to create novel and desirable phenotypes that genetic variety cannot provide [36][37]. It was further confirmed that, because DM is linked to gene expression, alterations in the methylation of areas that influence gene expression, such as cis-elements, may result in new gene expression and a new phenotype [36].

Plants can react to stress by adding a methyl group to DNA through DM. In Arabidopsis thaliana, for example, a gene called ATDM1 is responsible for drought stress response by methylating specific genes responsible for drought tolerance [38]. Pathogen infection can lead to DM changes, activating or repressing genes for defense. DM can silence genes and possibly recruit proteins that modify histones, leading to a more condensed chromatin structure and further repression of gene expression [24].

2.1.1. Mechanisms of DNA Methylation in Plant Development

DM is a complex process that involves multiple enzymes and cofactors. The process starts with the recognition of a CpG dinucleotide by a DNA methyltransferase enzyme [17]. This modification alters the chromatin structure, leading to gene transcription suppression due to the ability of DM to regulate gene expression during plant development and stress response. It regulates important plant traits such as leaf structure, disease resistance, and environmental stress resistance [31][39]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, DM effectively suppresses the expression of specific genes involved in flower development, thereby causing a delay in the flowering process [38]. This suppression is achieved through the methylation of distinct CpG islands in these genes’ promoter regions (Figure 2). In addition to regulating flowering, DM also plays a part in controlling leaf morphology, where it represses the expression of genes responsible for shaping and sizing leaves, resulting in the formation of smaller leaves [40]. Research has found that P. syringae pv. tomato (Pst), a type of bacterial pathogen, can trigger defense and hormone pathways via DM [17][41]. Arabidopsis uses a mechanism to enhance its resistance to the pathogen and prevent downy mildew disease caused by Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa). Additionally, DNA hypermethylation plays a crucial role in improving the plant’s immunity to two fungal pathogens, Plectosphaerella cucumerina, and Alternaria brassicicola, in Arabidopsis [42].

2.1.2. Role of DNA Methylation in Plant Stress Response

DM is essential for regulating gene expression and ensuring plant genome stability. Adding a methyl group to the cytosine residue of DNA creates 5-methylcytosine (5 mC) [4][38]. This 5 mC is involved in various biological processes (Figure 2), such as genome stability, transcriptional inactivity, developmental regulation, and response to environmental stress [35][43]. It acts as a repressive marker that suppresses gene expression, and its levels are regulated by both methylation and demethylation reactions [4]. DM can occur by either active or passive means, and its manipulation patterns could enhance crop yield, disease resistance, and tolerance to environmental stresses [39][44]. A study on salt-tolerance rice varieties and salt-sensitive has revealed that variations in global DM levels play a significant role in response to salt stress in regulating gene expression [45]. The research found that, under high salinity stress, promoter and gene body methylation levels are critical in regulating gene expression in a genotype and organ-specific manner.

Furthermore, the study also showed that plants responded to high salinity by reducing DM levels, which is associated with the upregulation of the DNA demethylase (DRM2) gene. Interestingly, this upregulation was observed only in the salt-sensitive cultivar and not in the salt-tolerant cultivar. These findings suggest that differential DM patterns can impact salt stress tolerance in plants. Another study on rice cultivars under salt stress found significant changes in roots with minor changes in leaves [46]. The results suggest demethylation, with some persistent changes even after stress removal. The difference may be due to different detection methods or different rice lines used. An apple study underlined the significance of epigenetic modifications in response to dormancy produced by low temperatures. High freezing temperatures reduced total methylation, which resulted in the resumption of active development and subsequent fruit set in apples [47][48]. Research in Populus trichocarpa demonstrated that drought stress treatment might modify DM levels, altering the expression patterns of numerous drought stress-responsive genes [49], although the molecular mechanism behind this induction is unknown. The network and various plant species involved in epigenetic modifications in response to abiotic stress are shown in Table 1. The findings from the studies are itemized in the table as changes in various DMs under stress and shed light on plant responses to adverse conditions.

Table 1. Studies on DNA methylation in different plant species under stress.

| Stress | Plants | Processes | Mechanisms/Responses | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat | Zea mays | DM analysis | Enhancing adequate tolerance to heat and increase in methylation | [50] |

| Brassica napus | Msap | Both the heat-tolerant genotype and heat-sensitive genotype improve the DM | [51] | |

| Gossypium | Regulation of anther development | Increase in DM | [46][52] | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Mouse-ear cress (A. thaliana) | The process of increasing the activity of epigenetic modulators. | [53] | |

| Drought | Medicago sativa | DM change | Decrease in DM processes | [54] |

| Oryza sativa | Msap | Genome site-specific methylation deference | [55][56] | |

| Physcomitrella patens and Arabidopsis thaliana | DM of gene promoters | Enhanced ABA represses gene expression | [41][57] | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Drought transcriptome analysis | Improved water retention, increase transposon expression and limit global genome methylation | [29][42] | |

| Zea mays | Transcriptome, miRNA, DM analysis | Promote water retention | [14][58][59] | |

| Populus trichocarpa | BS-seq | Enhanced the methylated cytosines amount | [60] | |

| Heavy metals | Arabidopsis thaliana | Msap | Increase in DM | [34] |

| Groceria Dura | Msap | Enhanced the DM | [34][61] | |

| Trifolium repens | DM Analysis | Hypomethylation in tolerant upon prolong exposure | [62] | |

| Oryza sativa | Msap | DM | [63] | |

| Cold | Prunus simonii | Msap | Cytosine methylation | [56] |

| Alpine | Msap | Cytosine methylation | [64] | |

| Salt | Glycine max | Expression of various transcription factors | Demethylation and hypomethylation tolerant and susceptibility | [65] |

| Oryza sativa | ELISA-based assay | Hypomethylation intolerant cultivar | [62] | |

| Brassica napus | Msap | Hypomethylation intolerant and hypermethylation in sensitive cultivars | [66] |

Keys: Msap = Methylation sensitive amplification polymorphism; DM = DNA methylation.

Wang et al. [40] demonstrated that drought stress induces changes in DM patterns in various plant species’ stress responses. In Arabidopsis thaliana, drought stress leads to global DNA hypomethylation, particularly in repetitive sequences and transposable elements [67]. This hypomethylation is associated with the upregulation and enhancement of drought-tolerance plant and responsiveness genes [43]. Within laboratory settings, specific stress treatments, such as extended or repeated exposure to elevated temperatures, may activate transgenes or TEs and impact surrounding genes [44]. Conversely, research has shown that Oryza sativa transcriptional regulation may cause transient hypermethylation of TEs near stress-inducing genes in low-phosphate responses [68]. Moreover, certain DNA demethylases have demonstrated the capacity to focus transcriptional regulation techniques available for enhancing stressful genes [69].

It is worth noting that environmental stressors cause DM and demethylation in various plant species [53][70]. Even in the absence of the original stress, these alterations can be retained and passed down to the progeny/offspring. However, the shift in DM is not consistent between stress events and plant species. For example, Eichten et al. [71], demonstrated that DM patterns in maize are inconsistent when the plants are exposed to a cold, heat, and UV irradiation. As a result, the inheritance of alterations in DM in corn, presumably connected to phenotypic changes, is unlikely to be strong. However, DM has demonstrated some consistency in terms of heredity in other tests. In rice, for example, a methyl-sensitive amplified fragment polymorphism study indicated that laser-induced DM is heritable and has triggered the production of micro-inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) [72].

Similarly, Pathak et al. [73] confirmed that in rice (Oryza sativa), salt stress leads to both hypermethylation and hypomethylation of specific genomic regions. Research has shown that changes in DM can alter gene expression patterns and increase salt tolerance [33]. In addition, pathogen infection can cause changes in DM patterns in plants. For example, infection with Pseudomonas syringae, a bacterial pathogen, can lead to dynamic changes in DM patterns, particularly in defense-related genes in Arabidopsis. These changes activate defense responses and improve resistance to pathogen infection [32][42]. In Zea mays, DM patterns in genes involved in defense responses change due to insect herbivory, resulting in improved resistance to herbivory [74][75]. These DM modifications are linked to altered gene expression patterns [76]. More research is needed to comprehend how DM regulates stress-responsive gene expression and how these epigenetic modifications are inherited across generations.

2.2. Histone Modification (HM)

Chromatin and gene expression are regulated by histone modifications (HMs), which can either activate or repress gene expression (Figure 2), depending on the type of HM and its location [77]. Research shows that HMs are dynamically regulated during plant stress responses. Research has demonstrated that drought stress can alter histone acetylation, leading to upregulation of stress-responsive genes [26][78][79]. Their research findings demonstrate the significance of HMs in plant stress responses and offer insights into the underlying regulatory mechanisms. In plants, HM has been found to play a significant role in stress response when the stressors are biotic or abiotic. For instance, trichostatin A, which is a histone deacetylase inhibitor, has been demonstrated to enhance resistance to the fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea in Arabidopsis thaliana [78][80].

Furthermore, abiotic stress factors like drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and heavy metals trigger complex signaling pathways in plants, leading to changes in histone modifications. Studies have shown that drought stress increases histone H3 acetylation levels, affecting stress-responsive genes in Arabidopsis thaliana [77][81]. This acetylation is linked to the activation of stress-responsive genes, implying a direct relationship connecting histone changes and the plant’s ability to adapt to water deprivation.

Similarly, salt stress has been found to induce changes in histone methylation patterns, affecting the expression of genes involved in ion homeostasis and osmotic regulation [82]. Cold stress increases chromatin accessibility in potato (Solanum tuberosum) via bivalent histone modifications (H3K4me3 and H3K27me3) of activated genes [83]. In fact, SHORT LIFE, a plant-specific methylation reader protein that identifies both active (H3K4me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) marks, was recently discovered [82]. Extreme temperatures modulate heat stress-responsive genes, highlighting the dynamic nature of histone modifications [22][77][84]. Histone acetylation is crucial in a plant’s stress response because studies have shown that HDA6 histone deacetylase controls stress-responsive genes and is critical for drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana [44][79][85]. However, histone methylation (HMT) is considered a complex modification that can activate or repress gene expression [78], in which the degree of methylation and specific residue modification are vital factors [84]. On the other hand, histone phosphorylation through protein kinases is crucial for plant stress responses, like the H3S10ph phosphorylation induced by salt, cold, and drought stress, potentially leading to upregulation or silencing of stress-responsive genes [86]. The MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) cascade is believed to play a role in histone phosphorylation and gene expression changes during stress responses [77][87]. HMs like acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, and ADP-ribosylation can affect plants’ gene expression and chromatin structure. They play a role in stress-signaling pathways, although their exact function in plant stress response still needs to be fully understood [86].

Mechanisms of Histone Modification in Plant Stress Response

The precise mechanisms by which histone modifications regulate gene expression during plant stress responses are still being elucidated. However, several key mechanisms have been proposed based on studies of various plant species. One mechanism involves the recruitment of specific transcription factors or co-regulators to stress-responsive genes through the recognition of specific histone modifications with different environmental challenges (Table 2). To reduce agricultural losses, it is crucial to cultivate stress-tolerant crop varieties that can flourish in tough environments [88], and to accomplish this feat, it is essential to delve deeper into how plants react to stress and how chromatin states and histone modifications modulate gene expression [89][90]. For example, the binding of the WRKY transcription factor to H3K4me3 marks has been shown to activate the expression of stress-related genes in Arabidopsis [84]. Studies have revealed the significant role that post-translational modifications (PTMs) play, including seed formation, flowering, and responding to plant stresses [91]. Recent research found that reducing H3K27me3 deposition within the gene body region of drought stress-responsive TFs led to Arabidopsis drought stress tolerance [92]. Additionally, inoculation with B. cinerea was observed to significantly upregulate the genes DES, DOX1, and LoxD, which encode essential enzymes in the oxylipin pathway, as well as WRKY75, which encodes a stress-responsive TF in tomato (Lycopersicum esculentus) [93]. The activation of all pathogen-induced genes coincided with an increase in H3K4me3 and H3K9ac levels. In reaction with Pst DC3000, the same genes were activated. An elevation in H3K4me3 and H3K9ac was also found with this pathogen; however, it was substantially smaller than with B. cinerea-coupled DES and DOX1. WRKY75, on the other hand, exhibited a large rise in both histone marks along the gene.

Table 2. Histone modification responses to stress in plant species.

| Stress Response | Plant Species | HM Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | Gossypium hirsutum | Improved drought tolerance by decreasing H3K9ac levels in the GhWRKY33 promoter via GhHDT4D, an HD2 histone deacetylase. | [94] |

| Triticulum aestivum | Drought stress downregulated 5 HDA genes and upregulated TaHAC2 in drought-resistant BL207 | [95] | |

| Dendrobium hirsutum | Under drought stress, the DoHDA10 and DoHDT4 genes are expressed in the roots, stems, and leaves. | [96] | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | HDA9 reduces plant drought sensitivity via H3K9ac in 14 genes during water deficit | [97] | |

| Brassica rapa | Drought treatment significantly increases the expression of 9 HAT genes, aiding drought stress response and adaptation. | [98] | |

| Oryza sativa | Nine HAT genes are triggered under drought conditions, some with MBS drought-sensitive elements in their promoter regions | [99] | |

| Heat | Arabidopsis thaliana | HDA9 removes the histone variant H2A.Z from the YUC8 nucleosome, activating transcription via phytochrome interacting factor4 and mediating thermo-morphogenesis | [100] |

| HDA9 interacts with PWR and regulates thermomorphogenesis via phytochrome interacting factor4 and YUC8 genes. | [101] |

Various abiotic factors, such as heat, salt, or limited water, can increase histone modification on a global scale, particularly in Arabidopsis with 12 different genetic families [102] (Table 3). Plants have eight histone lysine methylation sites: H3K4, H3K9, H3K26, H3K27, H3K36, H3K79, H4K20, and H1K26. Six arginine methylation sites are also present: H3R2, H3R8, H3R17, H3R26, H4R3, and H4R17 [13][82][103][104]. However, when Arabidopsis experiences drought stress, it results in an improvement in H3K4me3 and H3K9ac in the promoter areas of stress-responsive genes like RD20, RD29A, RAP2.4, and RD29B [105][106]. Furthermore, drought stress causes histone H3K4me1, H3K4me2, and H3K4me3 modifications throughout the Arabidopsis genome [107]. In rice seedlings under drought stress, 4837 genes exhibit differentially modified H3K4me3 [108][109]. Another mechanism involves the establishment of a “histone code” where multiple HMs act in conjunction to regulate gene expression. For instance, the interplay between H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 marks has been implicated in balancing gene activation and repression during stress responses. Additionally, histone modifications can also influence chromatin structure and accessibility by recruiting chromatin remodeling complexes or altering nucleosome stability.

Table 3. Enzymatic groups catalyzing Histone modifications in Arabidopsis.

| Histone Group | Gene | Target | Role in Stress | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deacetylases | At3G44680 | H3K9 | Improve salinity and drought resistance | [97][110] |

| At3G44750 | H3K18 | Repressed in the activation of ABA pathways and salt tolerance | [30] | |

| At2G27840 | H3K27 | Drought and cold resistance and salinity tolerance | [111] | |

| At3G18520 | Drought resistance | [30][112] | ||

| At5G09230 | H3K9 | Ethylene response | [43] | |

| At5G63110 | H3K9, | Pathogen defense, heat and cold tolerance | [113] | |

| Lysine Methyltransferase | At5G42400 | H3K4 | Enhanced plant immunity and heat defense | [13][114] |

| At4G27910 | H3K4 | Drought resistance | [115] | |

| At2G31650 | H3K4 | Enhance the tolerance of heat, osmotic reactions, and dehydration of plant stress | [13] | |

| At4G31120 | H4R3 | Salinity tolerance and drought resistance | [116] | |

| At1G77300 | H3K36 | Immunity defense | [114] | |

| At5G53430 | H3K4 | Drought resistance | [115] | |

| Acetyltransferases | At3G12980 | H3K9 | Ethylene response | [117] |

| At1G79000 | H4K14, H3K9 | Heat tolerance and ethylene response | [117][118] | |

| At5G50320 | H3K56 | Efficient UVB light responses | [119] | |

| At5G09740 | H4K5 | Adequate UV light responses, repair of DNA | [120] | |

| At3G54610 | H3K14 | Salt tolerance, cold tolerance, and decreasing heat stress | [107][121] | |

| At5G64610 | H4K5 | UV light responses, repair of DNA | [120] | |

| Demethylases | At4G00990 | H3K9me2 | Activation of the ABA pathways and drought tolerance | [103] |

| At4G20400 | H3K4me1/2/3 | High temperature and decreasing the salt stress | [122] | |

| At1G63490 | H3K4me1/2/3 | Dehydration | [109] | |

| At2G34880 | H3K4me1/2/3 | High temperature and salinity tolerance | [104][122] | |

| At3G45880 | H3K27me3 | Cold tolerance and heat stress reduction | [121] |

The dynamic nature of plants enables them to adapt to environmental changes quickly. Although some progress has been made in understanding the impact of histone modifications on plant stress responses, many details remain to be clarified. In the future, researchers should concentrate on uncovering the exact mechanisms that govern histone modification-mediated gene regulation and identifying the specific readers and erasers of histone modifications that participate in stress signaling pathways.

2.3. Small RNA-Mediated Gene Silencing

Small RNA-mediated gene silencing and chromatin remodeling complexes are key players in plant stress mechanisms [123], like miRNAs and siRNAs (Figure 2), which regulate gene expression during stress [106]. These short, non-coding RNA molecules guide the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to target mRNAs for degradation or translational repression. miRNAs are derived from endogenous hairpin-shaped precursors, while siRNAs are derived from exogenous double-stranded RNA or endogenous long double-stranded RNA precursors [124]. Both types of small RNAs function by base pairing with target mRNAs, resulting in mRNA cleavage or translational inhibition [105]. According to studies by Zhou et al. [125] and Singroha et al. [126], during drought stress, plants generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) in their chloroplasts and peroxisomes. However, to combat the damaging effects of ROS on cells, plants generate antioxidative enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, catalase, glutathione reductase, and ascorbate peroxidase [125][127]. Interestingly, some plant miRNAs, such as miR398 and miR528, are known to regulate oxidative stress networks [126][128][129].

Recent findings also indicate that stress-responsive miRNAs modulates plant stress tolerance by targeting stress-related genes [130]. Emerging evidence suggests that stress-induced lncRNAs regulate stress-responsive genes and pathways [130]. These RNAs can bind to messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and prevent their translation into proteins, or they can induce the degradation of specific mRNAs [131]. MiRNAs are used by plants to adapt to abiotic stress, such as drought and heat, and miR159 has been shown to modulate drought tolerance genes in Arabidopsis thaliana [86][131][132].

In plant stress response, small RNAs can be generated from stress-responsive genes or transposable elements that are activated under stress conditions [130]. Plants use small RNA molecules to regulate stress-responsive genes, where the mechanism enables them to adapt and thrive in challenging conditions. One example is miR398, which becomes active in oxidative stress and helps target the transcripts of copper superoxide dismutase (CSD) gene in Arabidopsis thaliana [126][131]. By repressing CSD expression, miR398 improves plant sensitivity to oxidative stress.

Small RNAs regulate genes at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional stages [106] and are also active in chromatin remodeling complexes, which alter chromatin structure to enable or restrict regulatory protein access to DNA, which, in turn, modifies gene expression [38][130]. In this RNA pathway, siRNAs produced by transposable elements or other repetitive sequences guide DNA methyltransferase DRM2 to specific genomic locations, resulting in gene silencing [133]. The Rd DM pathway has been related to plant stress response, regulating stress-responsive genes such as those producing heat shock proteins in Arabidopsis [115]. Furthermore, small RNAs can also interact with other chromatin remodeling complexes, such as histone modifiers, to regulate gene expression. Small RNAs can direct histone modifiers to specific genomic areas, causing HMs and gene expression to vary [105]. In Arabidopsis, for example, miR156 controls flowering time by targeting Squamosa promoter-binding protein-like transcription factors [106]. The interaction between miR156 and SPLs influences HMs at the flowering locus, thereby modulating flowering time.

In conclusion, the stress response of plants heavily relies on the critical role played by small RNA-mediated gene silencing and chromatin remodeling complexes. Small RNAs effectively regulate gene expression by targeting mRNAs by directing and guiding complexes that modify chromatin structure to specific locations within the genome. Such mechanisms allow plants to adapt to varying environmental conditions by precisely adjusting their stress responses.

2.4. Chromatin Remodeling Complexes

In plants, chromatin remodeling complexes play an important role in the epigenetic control of gene expression, particularly in response to stress [36][71][134]. These complexes are in charge of modifying chromatin shape, impacting DNA accessibility to transcriptional machinery and regulatory proteins [134]. In the context of plant stress, such as abiotic and biotic challenges, chromatin remodeling complexes play a role in modifying the expression of stress-responsive genes, affecting the plant’s capacity to adapt and survive under adverse conditions [135]. Plants respond to stress by reprogramming gene expression patterns through chromatin remodeling complexes, which promote structural modifications to activate or repress stress-responsive genes, ensuring survival and fine-tuning gene expression [86].

Chromatin remodeling complexes in plant stress responses alter gene expression by using ATP hydrolysis energy to slide, evict, or change nucleosome composition [127]. Histone-modifying enzymes catalyze posttranslational alterations of histone proteins, stimulating or inhibiting gene transcription. When extremely condensed, the chromatin arrangement prohibits transcription factors, polymerases, and other nuclear proteins from accessing DNA because some chromatin structural changes occur as a result of stress signals, allowing DNA to become accessible [16]. Chromatin remodeling complexes play a crucial role in epigenetic regulation, enabling fast, reversible changes in gene expression in response to plant stress [136]. This dynamic control allows plants to effectively respond to various stressors without altering the underlying genetic code. To organize complete responses to stress, chromatin remodeling complexes collaborate with other epigenetic processes, including DM and small RNA-mediated silencing pathways. Cross-talk between these multiple levels of epigenetic regulation leads to plant stress response, resilience, and adaptability. Furthermore, new data reveal that environmental signals can impact the activity and specificity of chromatin remodeling complexes, establishing a direct relationship between external stimuli and epigenetic changes that influence stress-responsive gene expression [118][137].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants13020163

References

- Hemenway, E.A.; Gehring, M. Epigenetic Regulation during Plant Development and the Capacity for Epigenetic Memory. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 87–109.

- Lu, X.; Hyun, T.K. The role of epigenetic modifications in plant responses to stress. Bot. Serbica 2021, 45, 3–12.

- Lloyd, J.P.B.; Lister, R. Epigenome plasticity in plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 55–68.

- Chachar, S.; Chachar, M.; Riaz, A.; Shaikh, A.A.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Guan, C.; Zhang, P. Epigenetic modification for horticultural plant improvement comes of age. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 292, 110633.

- Akhter, Z.; Bi, Z.; Ali, K.; Sun, C.; Fiaz, S.; Haider, F.U.; Bai, J. In Response to Abiotic Stress, DNA Methylation Confers EpiGenetic Changes in Plants. Plants 2021, 10, 1096.

- Balazova, E.; Balazova, A.; Oblozinsky, M. Epigenetic Modifications in Plants-Impact on Phospholipid Signaling and Secondary Metabolism. Chem. Listy 2022, 116, 416–422.

- Zhou, J.-M.; Zhang, Y. Plant immunity: Danger perception and signaling. Cell 2020, 181, 978–989.

- Arnold, P.A.; Kruuk, L.E.B.; Nicotra, A.B. How to analyse plant phenotypic plasticity in response to a changing climate. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 1235–1241.

- Bakhtiari, M.; Formenti, L.; Caggìa, V.; Glauser, G.; Rasmann, S. Variable effects on growth and defense traits for plant ecotypic differentiation and phenotypic plasticity along elevation gradients. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 3740–3755.

- Jones, J.D.G.; Vance, R.E.; Dangl, J.L. Intracellular innate immune surveillance devices in plants and animals. Science 2016, 354, aaf6395.

- Huang, C.-Y.; Jin, H. Coordinated epigenetic regulation in plants: A potent managerial tool to conquer biotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 795274.

- Duarte-Aké, F.; Us-Camas, R.; De-la-Peña, C. Epigenetic Regulation in Heterosis and Environmental Stress: The Challenge of Producing Hybrid Epigenomes to Face Climate Change. Epigenomes 2023, 7, 14.

- Song, Z.-T.; Zhang, L.-L.; Han, J.-J.; Zhou, M.; Liu, J.-X. Histone H3K4 methyltransferases SDG25 and ATX1 maintain heat-stress gene expression during recovery in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2021, 105, 1326–1338.

- Sudan, J.; Raina, M.; Singh, R. Plant epigenetic mechanisms: Role in abiotic stress and their generational heritability. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 172.

- Bäurle, I.; Trindade, I. Chromatin regulation of somatic abiotic stress memory. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5269–5279.

- Bhadouriya, S.L.; Mehrotra, S.; Basantani, M.K.; Loake, G.J.; Mehrotra, R. Role of Chromatin Architecture in Plant Stress Responses: An Update. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 603380.

- Jogam, P.; Sandhya, D.; Alok, A.; Peddaboina, V.; Allini, V.R.; Zhang, B. A review on CRISPR/Cas-based epigenetic regulation in plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 219, 1261–1271.

- Liu, X.; Zhu, K.; Xiao, J. Recent advances in understanding of the epigenetic regulation of plant regeneration. Abiotech 2023, 4, 31–46.

- Saeed, F.; Chaudhry, U.K.; Bakhsh, A.; Raza, A.; Saeed, Y.; Bohra, A.; Varshney, R.K. Moving beyond DNA sequence to improve plant stress responses. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 874648.

- Sun, C.; Ali, K.; Yan, K.; Fiaz, S.; Dormatey, R.; Bi, Z.; Bai, J. Exploration of Epigenetics for Improvement of Drought and Other Stress Resistance in Crops: A Review. Plants 2021, 10, 1226.

- González, A.P.; Chrtek, J.; Dobrev, P.I.; Dumalasová, V.; Fehrer, J.; Mráz, P.; Latzel, V. Stress-induced memory alters growth of clonal offspring of white clover (Trifolium repens). Am. J. Bot. 2016, 103, 1567–1574.

- Miryeganeh, M. Plants’ Epigenetic Mechanisms and Abiotic Stress. Genes 2021, 12, 1106.

- Kawakatsu, T.; Nery, J.R.; Castanon, R.; Ecker, J.R. Dynamic DNA methylation reconfiguration during seed development and germination. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 171.

- Suelves, M.; Carrió, E.; Núñez-Álvarez, Y.; Peinado, M.A. DNA methylation dynamics in cellular commitment and differentiation. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2016, 15, 443–453.

- Duarte-Aké, F.; Us-Camas, R.; Cancino-García, V.J.; De-la-Peña, C. Epigenetic changes and photosynthetic plasticity in response to environment. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 159, 108–120.

- Kumar, V.; Thakur, J.K.; Prasad, M. Histone acetylation dynamics regulating plant development and stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 4467–4486.

- Li, S.; He, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chiang, V.L.; Li, W. Histone Acetylation Changes in Plant Response to Drought Stress. Genes 2021, 12, 1409.

- Qin, X.; Zhang, K.; Fan, Y.; Fang, H.; Nie, Y.; Wu, X.-L. The Bacterial MtrAB Two-Component System Regulates the Cell Wall Homeostasis Responding to Environmental Alkaline Stress. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02311–e02322.

- Ashapkin, V.V.; Kutueva, L.I.; Aleksandrushkina, N.I.; Vanyushin, B.F. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Plant Adaptation to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7457.

- Tu, Y.-T.; Chen, C.-Y.; Huang, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Yen, M.-R.; Hsieh, J.-W.A.; Chen, P.-Y.; Wu, K. HISTONE DEACETYLASE 15 and MOS4-associated complex subunits 3A/3B coregulate intron retention of ABA-responsive genes. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 882–897.

- Lämke, J.; Bäurle, I. Epigenetic and chromatin-based mechanisms in environmental stress adaptation and stress memory in plants. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 124.

- Ferrari, M.; Torelli, A.; Marieschi, M.; Cozza, R. Role of DNA methylation in the chromium tolerance of Scenedesmus acutus (Chlorophyceae) and its impact on the sulfate pathway regulation. Plant Sci. 2020, 301, 110680.

- Kovalchuk, I. Role of DNA methylation in genome stability. In Genome Stability, 2nd ed.; Kovalchuk, I., Kovalchuk, O., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 26, pp. 435–452.

- Sun, M.; Yang, Z.; Liu, L.; Duan, L. DNA Methylation in Plant Responses and Adaption to Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6910.

- Sadakierska-Chudy, A.; Kostrzewa, R.M.; Filip, M. A Comprehensive View of the Epigenetic Landscape Part I: DNA Methylation, Passive and Active DNA Demethylation Pathways and Histone Variants. Neurotox. Res. 2015, 27, 84–97.

- Tonosaki, K.; Fujimoto, R.; Dennis, E.S.; Raboy, V.; Osabe, K. Will epigenetics be a key player in crop breeding? Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 958350.

- Huang, H.; Wu, N.; Liang, Y.; Peng, X.; Shu, J. SLNL: A novel method for gene selection and phenotype classification. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 6283–6304.

- Lee, S.; Choi, J.; Park, J.; Hong, C.P.; Choi, D.; Han, S.; Choi, K.; Roh, T.-Y.; Hwang, D.; Hwang, I. DDM1-mediated gene body DNA methylation is associated with inducible activation of defense-related genes in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 106.

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, J. Epigenetic Regulation of Nitrogen Signaling and Adaptation in Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 2725.

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Tan, M.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W.; You, J.; Wang, L.; Yan, X.; Wang, W. The pattern of alternative splicing and DNA methylation alteration and their interaction in linseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) response to repeated drought stresses. Biol. Res. 2023, 56, 12.

- Surdonja, K.; Eggert, K.; Hajirezaei, M.-R.; Harshavardhan, V.T.; Seiler, C.; Von Wirén, N.; Sreenivasulu, N.; Kuhlmann, M. Increase of DNA Methylation at the HvCKX2.1 Promoter by Terminal Drought Stress in Barley. Epigenomes 2017, 1, 9.

- López Sánchez, A.; Stassen, J.H.M.; Furci, L.; Smith, L.M.; Ton, J. The role of DNA (de)methylation in immune responsiveness of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2016, 88, 361–374.

- Zhang, H.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 489–506.

- Asensi-Fabado, M.-A.; Amtmann, A.; Perrella, G. Plant responses to abiotic stress: The chromatin context of transcriptional regulation. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2017, 1860, 106–122.

- Ferreira, L.J.; Azevedo, V.; Maroco, J.; Oliveira, M.M.; Santos, A.P. Salt Tolerant and Sensitive Rice Varieties Display Differential Methylome Flexibility under Salt Stress. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124060.

- Wang, W.; Huang, F.; Qin, Q.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Fu, B. Comparative analysis of DNA methylation changes in two rice genotypes under salt stress and subsequent recovery. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 465, 790–796.

- Saraswat, S.; Yadav, A.K.; Sirohi, P.; Singh, N.K. Role of epigenetics in crop improvement: Water and heat stress. J. Plant Biol. 2017, 60, 231–240.

- Kumar, G.; Rattan, U.K.; Singh, A.K. Chilling-mediated DNA methylation changes during dormancy and its release reveal the importance of epigenetic regulation during winter dormancy in apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149934.

- Liang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Huang, C.; Shuai, P.; Ye, C.-Y.; Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; et al. Single-base-resolution methylomes of populus trichocarpa reveal the association between DNA methylation and drought stress. BMC Genet. 2014, 15, S9.

- Chen, R.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Duan, L.; Sun, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Z. Continuous salt stress-induced long non-coding RNAs and DNA methylation patterns in soybean roots. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 730.

- Shankar, R.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Jain, M. Transcriptome analysis in different rice cultivars provides novel insights into desiccation and salinity stress responses. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23719.

- Deleris, A.; Halter, T.; Navarro, L.J.A.r.o.p. DNA Methylation and Demethylation in Plant Immunity. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2016, 54, 579–603.

- Al-Lawati, A.; Al-Bahry, S.; Victor, R.; Al-Lawati, A.H.; Yaish, M.W. Salt stress alters DNA methylation levels in alfalfa (Medicago spp.). Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 15018299.

- Ventouris, Y.E.; Tani, E.; Avramidou, E.V.; Abraham, E.M.; Chorianopoulou, S.N.; Vlachostergios, D.N.; Papadopoulos, G.; Kapazoglou, A. Recurrent Water Deficit and Epigenetic Memory in Medicago sativa L. Varieties. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3110.

- Ferreira, L.J.; Donoghue, M.T.A.; Barros, P.; Saibo, N.J.; Santos, A.P.; Oliveira, M.M. Uncovering Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) in a Salt-Tolerant Rice Variety under Stress: One Step towards New Regulatory Regions for Enhanced Salt Tolerance. Epigenomes 2019, 3, 4.

- Kumar, S.; Seem, K.; Mohapatra, T. Biochemical and Epigenetic Modulations under Drought: Remembering the Stress Tolerance Mechanism in Rice. Life 2023, 13, 1156.

- Garg, R.; Narayana Chevala, V.V.S.; Shankar, R.; Jain, M. Divergent DNA methylation patterns associated with gene expression in rice cultivars with contrasting drought and salinity stress response. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14922.

- Min, H.; Chen, C.; Wei, S.; Shang, X.; Sun, M.; Xia, R.; Liu, X.; Hao, D.; Chen, H.; Xie, Q. Identification of drought tolerant mechanisms in maize seedlings based on transcriptome analysis of recombination inbred lines. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1080.

- Aravind, J.; Rinku, S.; Pooja, B.; Shikha, M.; Kaliyugam, S.; Mallikarjuna, M.G.; Kumar, A.; Rao, A.R.; Nepolean, T. Identification, characterization, and functional validation of drought-responsive microRNAs in subtropical maize inbreds. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 941.

- Virlouvet, L.; Fromm, M. Physiological and transcriptional memory in guard cells during repetitive dehydration stress. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 596–607.

- Chung, S.; Kwon, C.; Lee, J.-H. Epigenetic control of abiotic stress signaling in plants. Genes Genom. 2022, 44, 267–278.

- Arora, H.; Singh, R.K.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, N.; Panchal, A.; Das, T.; Prasad, A.; Prasad, M. DNA methylation dynamics in response to abiotic and pathogen stress in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 1931–1944.

- Zhang, W.; Wang, N.; Yang, J.; Guo, H.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Li, S.; Xiang, F. The salt-induced transcription factor GmMYB84 confers salinity tolerance in soybean. Plant Sci. 2020, 291, 110326.

- Ramegowda, V.; Gill, U.S.; Sivalingam, P.N.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, C.; Govind, G.; Nataraja, K.N.; Pereira, A.; Udayakumar, M.; Mysore, K.S.; et al. GBF3 transcription factor imparts drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9148.

- Gunapati, S.; Naresh, R.; Ranjan, S.; Nigam, D.; Hans, A.; Verma, P.C.; Gadre, R.; Pathre, U.V.; Sane, A.P.; Sane, V.A. Expression of GhNAC2 from G. herbaceum, improves root growth and imparts tolerance to drought in transgenic cotton and Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24978.

- Rehman, M.; Tanti, B. Understanding epigenetic modifications in response to abiotic stresses in plants. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 27, 101673.

- Luo, X.; He, Y. Experiencing winter for spring flowering: A molecular epigenetic perspective on vernalization. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 104–117.

- Secco, D.; Wang, C.; Shou, H.; Schultz, M.D.; Chiarenza, S.; Nussaume, L.; Ecker, J.R.; Whelan, J.; Lister, R. Stress induced gene expression drives transient DNA methylation changes at adjacent repetitive elements. eLife 2015, 4, e09343.

- Le, T.-N.; Schumann, U.; Smith, N.A.; Tiwari, S.; Au, P.C.K.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Taylor, J.M.; Kazan, K.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Zhang, R.; et al. DNA demethylases target promoter transposable elements to positively regulate stress responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 458.

- Yaish, M.W. Editorial: Epigenetic Modifications Associated with Abiotic and Biotic Stresses in Plants: An Implication for Understanding Plant Evolution. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1983.

- Eichten, S.R.; Springer, N.M. Minimal evidence for consistent changes in maize DNA methylation patterns following environmental stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 308.

- Li, S.; Xia, Q.; Wang, F.; Yu, X.; Ma, J.; Kou, H.; Lin, X.; Gao, X.; Liu, B. Laser Irradiation-Induced DNA Methylation Changes Are Heritable and Accompanied with Transpositional Activation of mPing in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 363.

- Pathak, H.; Kumar, M.; Molla, K.A.; Chakraborty, K. Abiotic stresses in rice production: Impacts and management. Oryza 2021, 58, 103–125.

- Feng, S.J.; Liu, X.S.; Tao, H.; Tan, S.K.; Chu, S.S.; Oono, Y.; Zhang, X.D.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.M. Variation of DNA methylation patterns associated with gene expression in rice (Oryza sativa) exposed to cadmium. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 2629–2649.

- Zheng, H.; Fan, X.; Bo, W.; Yang, X.; Tjahjadi, T.; Jin, S. A Multiscale Point-Supervised Network for Counting Maize Tassels in the Wild. Plant Phenomics 2023, 5, 0100.

- Hawes, N.A.; Fidler, A.E.; Tremblay, L.A.; Pochon, X.; Dunphy, B.J.; Smith, K.F. Understanding the role of DNA methylation in successful biological invasions: A review. Biol. Invasions 2018, 20, 2285–2300.

- Nunez-Vazquez, R.; Desvoyes, B.; Gutierrez, C. Histone variants and modifications during abiotic stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 984702.

- Hu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, D.-X. Histone Acetylation Dynamics Integrates Metabolic Activity to Regulate Plant Response to Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1236.

- Zhao, T.; Zhan, Z.; Jiang, D. Histone modifications and their regulatory roles in plant development and environmental memory. J. Genet. Genom. 2019, 46, 467–476.

- Chakravarty, S.; Bhat, U.A.; Reddy, R.G.; Gupta, P.; Kumar, A. Chapter 25—Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors and Psychiatric Disorders. In Epigenetics in Psychiatry; Peedicayil, J., Grayson, D.R., Avramopoulos, D., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 515–544.

- Wollmann, H.; Stroud, H.; Yelagandula, R.; Tarutani, Y.; Jiang, D.; Jing, L.; Jamge, B.; Takeuchi, H.; Holec, S.; Nie, X.; et al. The histone H3 variant H3.3 regulates gene body DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 94.

- Ueda, M.; Seki, M. Histone Modifications Form Epigenetic Regulatory Networks to Regulate Abiotic Stress Response1 . Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 15–26.

- Zeng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Marand, A.P.; Zhu, B.; Buell, C.R.; Jiang, J. Cold stress induces enhanced chromatin accessibility and bivalent histone modifications H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 of active genes in potato. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 123.

- Wu, R.; Wang, T.; Richardson, A.C.; Allan, A.C.; Macknight, R.C.; Varkonyi-Gasic, E. Histone modification and activation by SOC1-like and drought stress-related transcription factors may regulate AcSVP2 expression during kiwifruit winter dormancy. Plant Sci. 2019, 281, 242–250.

- Kim, J.-M.; Sasaki, T.; Ueda, M.; Sako, K.; Seki, M. Chromatin changes in response to drought, salinity, heat, and cold stresses in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 114.

- Wang, L.; Qiao, H. Chromatin regulation in plant hormone and plant stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 57, 164–170.

- Mozgova, I.; Mikulski, P.; Pecinka, A.; Farrona, S. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Abiotic Stress Response and Memory in Plants. In Epigenetics in Plants of Agronomic Importance: Fundamentals and Applications: Transcriptional Regulation and Chromatin Remodelling in Plants; Alvarez-Venegas, R., De-la-Peña, C., Casas-Mollano, J.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–64.

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.-K. Developing naturally stress-resistant crops for a sustainable agriculture. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 989–996.

- Ageeva-Kieferle, A.; Georgii, E.; Winkler, B.; Ghirardo, A.; Albert, A.; Hüther, P.; Mengel, A.; Becker, C.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Durner, J.; et al. Nitric oxide coordinates growth, development, and stress response via histone modification and gene expression. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 336–360.

- Ramakrishnan, M.; Papolu, P.K.; Satish, L.; Vinod, K.K.; Wei, Q.; Sharma, A.; Emamverdian, A.; Zou, L.-H.; Zhou, M. Redox status of the plant cell determines epigenetic modifications under abiotic stress conditions and during developmental processes. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 42, 99–116.

- Zhou, B.; Zeng, L. Conventional and unconventional ubiquitination in plant immunity. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 1313–1330.

- Ramirez-Prado, J.S.; Latrasse, D.; Rodriguez-Granados, N.Y.; Huang, Y.; Manza-Mianza, D.; Brik-Chaouche, R.; Jaouannet, M.; Citerne, S.; Bendahmane, A.; Hirt, H.; et al. The Polycomb protein LHP1 regulates Arabidopsis thaliana stress responses through the repression of the MYC2-dependent branch of immunity. Plant J. 2019, 100, 1118–1131.

- Crespo-Salvador, Ó.; Sánchez-Giménez, L.; López-Galiano, M.J.; Fernández-Crespo, E.; Schalschi, L.; García-Robles, I.; Rausell, C.; Real, M.D.; González-Bosch, C. The Histone Marks Signature in Exonic and Intronic Regions Is Relevant in Early Response of Tomato Genes to Botrytis cinerea and in miRNA Regulation. Plants 2020, 9, 300.

- Zhang, J.-B.; He, S.-P.; Luo, J.-W.; Wang, X.-P.; Li, D.-D.; Li, X.-B. A histone deacetylase, GhHDT4D, is positively involved in cotton response to drought stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 104, 67–79.

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Pei, X.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Comparative Genome-Wide Analysis and Expression Profiling of Histone Acetyltransferases and Histone Deacetylases Involved in the Response to Drought in Wheat. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 1065–1078.

- Zhang, M.; da Silva, J.A.T.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H.; Si, C.; Zhao, C.; He, C.; Duan, J. Identification of histone deacetylase genes in Dendrobium officinale and their expression profiles under phytohormone and abiotic stress treatments. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10482.

- Zheng, Y.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Xie, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Su, L.; Wei, W.; Pan, L.; Zhou, D.-X. Histone deacetylase HDA9 negatively regulates salt and drought stress responsiveness in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 1703–1713.

- Eom, S.H.; Hyun, T.K. Histone Acetyltransferases (HATs) in Chinese Cabbage: Insights from Histone H3 Acetylation and Expression Profiling of HATs in Response to Abiotic Stresses. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2018, 143, 296–303.

- Hou, J.; Ren, R.; Xiao, H.; Chen, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Q.; Hou, H.; He, S.; Li, L. Characteristic and evolution of HAT and HDAC genes in Gramineae genomes and their expression analysis under diverse stress in Oryza sativa. Planta 2021, 253, 72.

- van der Woude, L.C.; Perrella, G.; Snoek, B.L.; van Hoogdalem, M.; Novák, O.; van Verk, M.C.; van Kooten, H.N.; Zorn, L.E.; Tonckens, R.; Dongus, J.A.; et al. HISTONE DEACETYLASE 9 stimulates auxin-dependent thermomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana by mediating H2A.Z depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 25343–25354.

- Shen, Y.; Lei, T.; Cui, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, Y.; Guérard, F.; Issakidis-Bourguet, E.; Zhou, D.-X. Arabidopsis histone deacetylase HDA15 directly represses plant response to elevated ambient temperature. Plant J. 2019, 100, 991–1006.

- Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324.

- Wang, Q.; Liu, P.; Jing, H.; Zhou, X.F.; Zhao, B.; Li, Y.; Jin, J.B. JMJ27-mediated histone H3K9 demethylation positively regulates drought-stress responses in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 221–236.

- Shen, Y.; Conde e Silva, N.; Audonnet, L.; Servet, C.; Wei, W.; Zhou, D.-X. Over-expression of histone H3K4 demethylase gene JMJ15 enhances salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 290.

- Jagadhesan, B.; Das, S.; Singh, D.; Jha, S.K.; Durgesh, K.; Sathee, L. Micro RNA mediated regulation of nutrient response in plants: The case of nitrogen. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2022, 27, 345–357.

- Begum, Y. Regulatory role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the recent development of abiotic stress tolerance of plants. Gene 2022, 821, 146283.

- Hu, Z.; Song, N.; Zheng, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Xing, J.; Ma, J.; Guo, W.; Yao, Y.; Peng, H.; et al. Histone acetyltransferase GCN5 is essential for heat stress-responsive gene activation and thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2015, 84, 1178–1191.

- Zhang, H.; Guo, F.; Qi, P.; Huang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, L.; Han, N.; Xu, L.; Bian, H. OsHDA710-Mediated Histone Deacetylation Regulates Callus Formation of Rice Mature Embryo. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 1646–1660.

- Zhu, A.; Greaves, I.K.; Dennis, E.S.; Peacock, W.J. Genome-wide analyses of four major histone modifications in Arabidopsis hybrids at the germinating seed stage. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 137.

- Mehdi, S.; Derkacheva, M.; Ramström, M.; Kralemann, L.; Bergquist, J.; Hennig, L. The WD40 Domain Protein MSI1 Functions in a Histone Deacetylase Complex to Fine-Tune Abscisic Acid Signaling. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 42–54.

- Han, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Hunter, D.; Luo, X.; Duan, J.; Tian, L. AtHD2D gene plays a role in plant growth, development, and response to abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 310.

- Lee, K.; Seo, P.J. Dynamic epigenetic changes during plant regeneration. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 235–247.

- Luo, M.; Cheng, K.; Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; Wu, K. Plant responses to abiotic stress regulated by histone deacetylases. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2147.

- Lee, S.; Fu, F.; Xu, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Yun, D.-J.; Mengiste, T. Global Regulation of Plant Immunity by Histone Lysine Methyl Transferases. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 1640–1661.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Yin, H.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Ahmad, R.; Liu, B.; Xu, Z.-Y. Trithorax-group proteins ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX4 (ATX4) and ATX5 function in abscisic acid and dehydration stress responses. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1582–1597.

- Fu, Y.-L.; Zhang, G.-B.; Lv, X.-F.; Guan, Y.; Yi, H.-Y.; Gong, J.-M. Arabidopsis Histone Methylase CAU1/PRMT5/SKB1 Acts as an Epigenetic Suppressor of the Calcium Signaling Gene CAS to Mediate Stomatal Closure in Response to Extracellular Calcium. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2878–2891.

- Li, C.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Yang, H. Involvement of Arabidopsis Histone Acetyltransferase HAC Family Genes in the Ethylene Signaling Pathway. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 426–435.

- Roca Paixão, J.F.; Gillet, F.-X.; Ribeiro, T.P.; Bournaud, C.; Lourenço-Tessutti, I.T.; Noriega, D.D.; Melo, B.P.d.; de Almeida-Engler, J.; Grossi-de-Sa, M.F. Improved drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis by CRISPR/dCas9 fusion with a Histone AcetylTransferase. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8080.

- Fina, J.P.; Masotti, F.; Rius, S.P.; Crevacuore, F.; Casati, P. HAC1 and HAF1 histone acetyltransferases have different roles in UV-B responses in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1179.

- Umezawa, T.; Sugiyama, N.; Takahashi, F.; Anderson, J.C.; Ishihama, Y.; Peck, S.C.; Shinozaki, K. Genetics and phosphoproteomics reveal a protein phosphorylation network in the abscisic acid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, rs8.

- Zheng, M.; Liu, X.; Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Xin, M.; Yao, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhou, D.-X.; Ni, Z.; et al. Histone acetyltransferase GCN5 contributes to cell wall integrity and salt stress tolerance by altering the expression of cellulose synthesis genes. Plant J. 2019, 97, 587–602.

- Cui, X.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Issakidis-Bourguet, E.; Zhou, D.-X. Metabolic control of histone demethylase activity involved in plant response to high temperature. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 1813–1828.

- Park, J.-J.; Dempewolf, E.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.-Y. RNA-guided transcriptional activation via CRISPR/dCas9 mimics overexpression phenotypes in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179410.

- Xie, M.; Yu, B. siRNA-directed DNA Methylation in Plants. Curr. Genom. 2015, 16, 23–31.

- Zhou, R.; Kong, L.; Yu, X.; Ottosen, C.-O.; Zhao, T.; Jiang, F.; Wu, Z. Oxidative damage and antioxidant mechanism in tomatoes responding to drought and heat stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2019, 41, 20.

- Singroha, G.; Sharma, P.; Sunkur, R. Current status of microRNA-mediated regulation of drought stress responses in cereals. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1808–1821.

- He, M.-Y.; Ren, T.X.; Jin, Z.D.; Deng, L.; Liu, H.J.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, X.X.; Yang, Y.; Chang, H. Precise analysis of potassium isotopic composition in plant materials by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2023, 209, 106781.

- Qiu, Z.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, L. Characterization of miRNAs and their target genes in He-Ne laser pretreated wheat seedlings exposed to drought stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 164, 611–617.

- Yang, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, Q.; Wang, J.; Huang, L.; Fu, S.; Qin, S.; Xie, X.; Ge, S.; Li, X.; et al. microRNAs: Key Players in Plant Response to Metal Toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8642.

- Zhan, J.; Meyers, B.C. Plant Small RNAs: Their Biogenesis, Regulatory Roles, and Functions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 21–51.

- Ferdous, J.; Hussain, S.S.; Shi, B.-J. Role of microRNAs in plant drought tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 293–305.

- Zemach, A.; Kim, M.Y.; Hsieh, P.-H.; Coleman-Derr, D.; Eshed-Williams, L.; Thao, K.; Harmer, S.L.; Zilberman, D. The Arabidopsis Nucleosome Remodeler DDM1 Allows DNA Methyltransferases to Access H1-Containing Heterochromatin. Cell 2013, 153, 193–205.

- Gallego-Bartolomé, J. DNA methylation in plants: Mechanisms and tools for targeted manipulation. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 38–44.

- Pandey, G.; Sharma, N.; Sahu, P.P.; Prasad, M. Chromatin-Based Epigenetic Regulation of Plant Abiotic Stress Response. Curr. Genom. 2016, 17, 490–498.

- Kim, J.H. Chromatin Remodeling and Epigenetic Regulation in Plant DNA Damage Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4093.

- Pecinka, A.; Chevalier, C.; Colas, I.; Kalantidis, K.; Varotto, S.; Krugman, T.; Michailidis, C.; Vallés, M.-P.; Muñoz, A.; Pradillo, M. Chromatin dynamics during interphase and cell division: Similarities and differences between model and crop plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5205–5222.

- Kim, J.-H. Multifaceted Chromatin Structure and Transcription Changes in Plant Stress Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2013.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!