Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Marine & Freshwater Biology

Copepods are the most abundant organisms in marine zooplankton and the primary components of the food chain. They are hotspots for highly adaptable microorganisms, which are pivotal in biogeochemical cycles. The microbiome, encompassing microorganisms within and surrounding marine planktonic organisms, holds considerable potential for biotechnological advancements. Despite marine microbiome research interests expanding, the understanding of the ecological interactions between microbiome and copepods remains limited.

- zooplankton

- microorganisms

- bacteria

- aquaculture

- biodegradation

1. Introduction

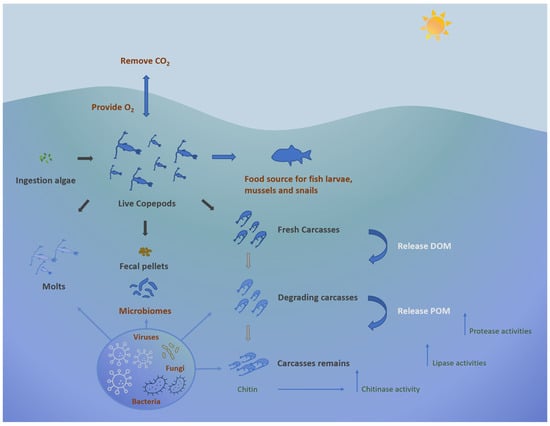

Plankton, including both phyto- and zooplanktonic organisms, are at the base of trophic webs in all aquatic ecosystems and contribute significantly to the biodiversity of marine ecosystems [1,2]. These organisms confer ecological benefits to marine environments; other than functioning as a crucial food source for many organisms, they participate in the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, generating oxygen [3]. Additionally, they contribute to the decomposition of deceased plants and animals, leading to the sequestration of both temporary and permanent carbon in the deep ocean. They participate in this carbon sequestration process alongside the microbial carbon pump, which involves mechanisms like the conversion of organic matter into dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and the subsequent temporary storage of this carbon in deeper waters until it is resurfaced through thermohaline circulation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ecological role of copepods in marine environment.

Among zooplankton, copepods, a class within the Crustacean subphylum, predominate as the most abundant multicellular organisms on Earth, potentially comprising 80% of the biomass of medium-sized zooplankton [4,5,6]. Current knowledge identifies more than 11,300 copepod species, showcasing their remarkable diversity and wide distribution across aquatic environments while also occurring in moist terrestrial habitats [7,8,9]. Copepods can be benthic-pelagic organisms, inhabiting the water column and sediment, and even include parasites [10,11]. Moreover, marine copepods play a critical role in the microbial loop, significantly contributing to the cycling of dissolved organic material (DOM) and microelements through their feeding activities [6,12,13]. Copepods also contribute to the release of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and particulate organic carbon (POC) during feeding and excretion, thus providing nutrients for associated microorganisms [14,15]. Collectively, copepods regulate microbial populations, recycle nutrients, and facilitate the transfer of energy within the food web. Due to their feeding habits, nutrient excretion, and vertical migration, copepods contribute to the overall productivity and function of aquatic ecosystems and are keystone organisms in marine food webs.

Due to the position of copepods in marine food chains, they are an important alternative to traditional live feed in aquaculture. In fact, in comparison to more conventional feeds such as Artemia and Rotifers, copepods demonstrate superior capacity in ensuring nutritional quality and enhancing the digestibility of food for animals [16]. Utilizing copepods in aquaculture offers several advantages, including improved growth, survival, tolerance, and a reduced incidence of deformities in fish larvae [17,18]. Extensive research has been dedicated to exploring the benefits of copepods in aquaculture [19,20,21,22], and the observed enhancements in fish larvae performance are also due to the microbiome associated with copepod cultures [23].

In recent years, symbiotic interactions in crustacean arthropods, such as copepods, have gained significant attention [24]. The microbiome associated with copepods is a key factor in regulating the overall energy balance of zooplankton, ensuring homeostasis, and influencing the cycling of organic matter in aquatic ecosystems [25,26]. Moreover, the gut microbiota of copepods acts as a driving force for their adaptation and acclimation to harmful cyanobacterial blooms by facilitating the degradation of toxic substances released by cyanobacteria [27]. Furthermore, microbial communities associated with copepod carcasses participate in the metabolic processing of nutrient uptake, including denitrification, particularly in anoxic environments [28,29].

2. Characterization of the Copepod-Associated Microbiome

Identifying microbiomes associated with aquatic organisms involves a combination of techniques to characterize the microbial communities living in and on these organisms. These techniques help to understand the diversity, composition, and functionality of the microbiota. Prior to the advent of molecular techniques, the identification and characterization of microbiota in environmental samples involved a culture-dependent approach. The method relies on growing microorganisms in a laboratory setting, usually on culture media, to isolate and identify them. Microorganisms were grown in isolated conditions under controlled conditions of temperature, pH, and oxygen [30]. This method allows the isolation and pure culture of specific microorganisms, providing the opportunity to study the physiology, metabolism, and characteristics of individual microorganisms. Microorganisms were identified through techniques such as microscopy, biochemical testing, and genetic sequencing. However, the culturomics approach has limitations due to the specific growth requirements of different organisms, and conventional microbiological techniques only capture a small fraction of the microbiota present in environmental samples. The process is time-consuming, as some microorganisms can take days or even weeks to grow. Additionally, laboratory culture conditions may not accurately represent the natural environment; they may overlook the most abundant microorganisms in the environment, including those that are not easily cultivable, leading to bias in the types of microorganisms that can be isolated [31].

Culture-independent molecular techniques, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) and meta-barcoding, have advanced our understanding of microbial diversity in marine and freshwater environments [32]. It is currently the most used method to analyze the microbiome, designed to study microorganisms without requiring their culture.

Analysis of genetic material directly from environmental samples can allow the identification and characterization of microorganisms [33]. It provides a more comprehensive view of the microbial community, as it can detect unculturable and rare microorganisms, allowing the study of the genetic content and biodiversity of entire microbiomes [34].

The advancement of genome sequencing technologies has revolutionized the field of microbiome research, with many studies employing Illumina short-read and nanopore long-read technologies for sequencing [35,36]. Illumina next-generation sequencing is a DNA sequencing technology used to determine the order of base pairs in DNA [37]. Currently, the most commonly used method for analyzing microbial communities associated with aquatic organisms is high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, predominantly performed on the Illumina platform [38,39,40]. The 16S rRNA gene contains nine hypervariable regions with distinct characteristics, with the V3 and V4 regions being the most frequently sequenced [41]. This technology can be utilized for various applications, such as whole genome and fragment sequencing, metagenomics, transcriptome analysis, and methylation analysis [42]. The process involves three fundamental steps: amplification, sequencing, and analysis [43].

This technique is faster and more efficient than a culture-dependent method. Its disadvantage is that it does not provide information on the physiological and metabolic characteristics of individual microorganisms and requires specialized equipment and expertise for genetic analysis. The functional roles of the copepod-associated microbiome are also being revealed [9]. For instance, Moisander et al. [39] employed 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to identify a high abundance of the Proteobacteria phylum in copepods, along with Planctomycetes. Shoemaker and Moisander [44] highlighted the importance of the copepod gut microbiome on the function of bacterioplankton in seawater, suggesting that despite low microbial abundance, copepods can contribute to bacterioplankton function across diverse oceanic regions. Yeh et al. [45] utilized 16S rDNA metabarcoding to analyze the eukaryotic and prokaryotic diversity in the gut contents of the copepod Calanus finmarchicus in the North Atlantic Ocean. This approach provided insights into the diet, microbiome, parasites, and pathogens of copepods. Notably, while Vibrio spp. Was commonly observed in culture-dependent studies, it was relatively rare in high-throughput sequencing analyses [9]. Overall, the combination of these techniques provides a more comprehensive understanding of the microbiome and its ecological role associated with aquatic life and is tailored to the specific research goals and the nature of the microbial community being studied.

3. Biodegradation Role of the Copepod-Associated Microbiome

Zooplankton and microorganisms can release and consume large amounts of particulate matter and dissolve organic compounds, and bacteria can thrive in the microhabitat of zooplankton by obtaining organic and inorganic nutrients. De Corte et al. [67] showed that the zooplankton-associated bacterial assemblage was able to metabolize chitin, taurine, and other organic macromolecules. This association mediates biogeochemical processes in environmental waters through the proliferation of specific bacterial populations.

Wäge et al. [125] found the presence of gut-specific prokaryotic taxa and indicator species of methanogenic pathways in both copepods. The relative abundance of archaea and methanogenic bacteria was examined and showed a high degree of variability among individual copepods, highlighting intra- and interspecific variation in copepod-associated prokaryotic communities. The results reveal that the guts of Temora sp. And Acartia sp. Have the potential to produce methane in trace amounts.

Gorokhova et al. [74] speculated that it is possible that the copepod gut, fecal pellets, and carcasses contained mercury-methylated bacteria [126]. In a clade-specific quantitative PCR assay of copepods and cladocerans, the authors found that the hgcA gene of the methylation-associated bacterial cluster was carried in both copepods, while it was not found in cladocerans. In contrast, the Hg methylation efficiency of fecal pellets was higher in copepods, and it is hypothesized that endogenous Hg methylation in zooplankton contributes to the regulation of methylmercury in marine fish. Its methylation capacity varied synchronously in the microbiome, and this observation contributes to the dynamics of methylmercury in marine food webs.

Sadaiappan et al. [127] studied five copepod genera, Acartia spp., Calanus spp., Centropages sp., Pleuromamma spp., and Temora spp., and their associated bacteriobiomes. Their meta-analysis revealed five copepod genera with bacteriobiomes capable of mediating methanogenesis and methane oxidation. Among them, the bacteriobiomes of Pleuromamma spp. Had potential genes for methanogenesis and nitrogen fixation, and the bacteriobiomes of Temora spp. Were involved in assimilatory sulfate reduction and cyanocobalamin synthesis. The bacteriobiomes of Pleuromamma spp. And Temora spp. Had potential genes responsible for iron transport. There are also flavobacteria clade members that degrade high-molecular-weight organic matter such as cellulose and chitin, which have symbiotic or parasitic interactions with zooplankton and can use the intestines of copepods as a host environment [128].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/w15244203

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!