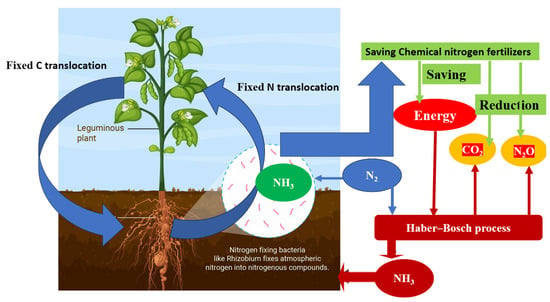

Nitrogen fixation has the potential to address the global protein shortage by increasing nitrogen supply in agriculture. However, the excessive use of synthetic fertilizers has led to environmental consequences and high energy consumption. To promote sustainable agriculture, alternative approaches such as biofertilizers that utilize biological nitrogen fixation have been introduced to minimize ecological impact. Understanding the process of biological nitrogen fixation, where certain bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, is crucial for sustainable agriculture. This knowledge helps reduce reliance on synthetic fertilizers and maintain soil fertility. The symbiotic relationship between Rhizobium bacteria and leguminous plants plays a vital role in sustainable agriculture by facilitating access to atmospheric nitrogen, improving soil fertility, and reducing the need for chemical fertilizers.

- nitrogen fertilizer

- Rhizobium

- legume

1. Introduction

Nitrogen, also known as N2, is a vital element that makes up 78% of Earth’s atmosphere [1]. It plays a crucial role in plant growth, with plants requiring larger amounts of nitrogen compared to other elements [2][3]. However, plants cannot directly use nitrogen gas due to its stability and strong triple bond between nitrogen atoms. They need nitrogen to be converted into reduced forms, which they obtain from various sources such as ammonia or nitrate fertilizers, organic matter decomposition, natural processes like lightning, and biological nitrogen fixation [4]. The production of fertilizers, insecticides, irrigation, and machinery for the green revolution heavily relies on fossil fuels, with approximately 80% of the world’s fossil energy being used [5][6]. Over the past four decades, global nitrogen fertilizer usage has significantly increased, contributing to over half of the energy consumed in agriculture [7][8]. The manufacturing process for nitrogen fertilizer using the Haber–Bosch process alone emits approximately 465 teragrams of carbon dioxide annually, making it a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions [9][10][11]. The nitrogen fertilizer industry has been found to contribute up to 1.2% of total greenhouse emissions resulting from human activities [5][12][13][14].

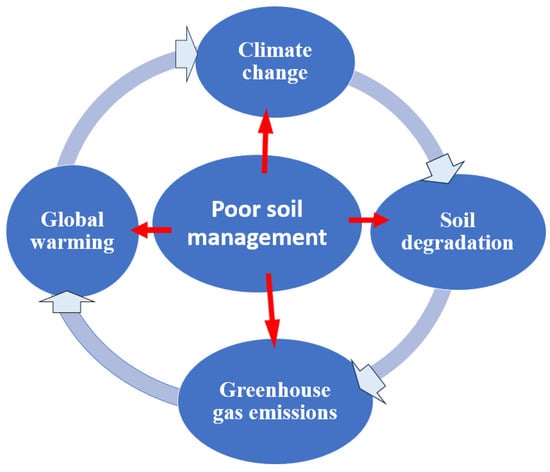

The fertilizer industry heavily relies on energy-intensive technologies for agricultural production, including the manufacture of nitrogen fertilizers and pesticides. Global nitrogen fertilizer consumption reached approximately 108 million tons in 2019 and slightly increased to 110 million tons in 2020–2021, with a projected annual growth rate of 4.1% until 2025–2026 [15]. However, the scarcity of fossil energy is a significant challenge that the world may face [16][17]. The excessive use of nitrogen fertilizer can have significant environmental consequences. One major issue is nutrient runoff, where high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus from synthetic fertilizers can be washed into nearby water bodies, causing eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, oxygen depletion, and disruption in aquatic ecosystems [18][19][20]. Another problem is soil degradation. Synthetic fertilizers primarily focus on macronutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, neglecting other essential micronutrients. This imbalanced nutrient application can deplete soil organic matter, damage its physical structure, decrease beneficial microbial activity, and reduce overall fertility over time [21][22][23]. Biodiversity loss is also a concern. Nutrient runoff leading to eutrophication can harm aquatic life, resulting in a decline in fish populations and other species. Moreover, the loss of soil fertility due to synthetic fertilizers can negatively affect soil organisms crucial for maintaining healthy soil and biodiversity, such as earthworms, beneficial insects, and microorganisms [24]. The production and distribution of synthetic fertilizers contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. This energy-intensive process relies on fossil fuels and releases carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and methane (CH4), exacerbating climate change [25].

To mitigate the consequences of unsustainable agricultural practices, several sustainable alternatives have been developed. These include organic farming, crop rotation, cover cropping, and the use of natural fertilizers such as compost and manure. By reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers, these practices promote environmental sustainability. Additionally, alternatives like biofertilizers and biopesticides have been embraced in modern agriculture. These options help alleviate energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and negative impacts of excessive nitrogen waste in agroecosystems [26][27]. Biofertilizers and biopesticides encourage biological nitrogen fixation, a process facilitated by microorganisms that significantly contribute to the nitrogen cycle and overall nitrogen balance. Global terrestrial biological nitrogen fixation is estimated to range from 52 to 130 teragrams (Tg) of nitrogen per year [28][29][30]. Biological nitrogen fixation aligns with the principles of green engineering as it relies on renewable sunlight and has minimal ecological impact [31][32].

2. Biological Nitrogen Fixation Systems

Rhizobium–Legume Symbiotic Relationship and Environmental Stress

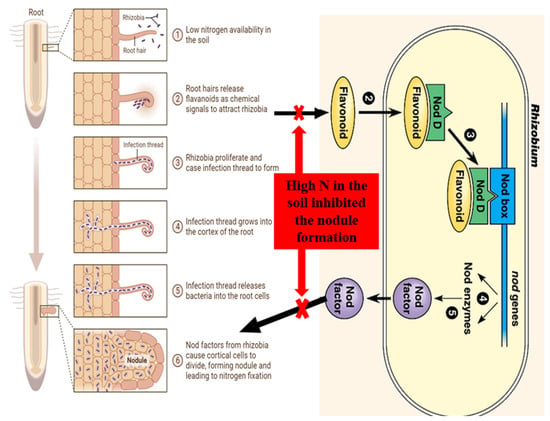

3. Effects of N Fertilizer on Rhizobium–Legume Molecular Signaling

3.1. Isoflavonoids

3.2. Nod Factors

3.3. Nodulation Receptor Kinases (NORKs)

3.4. Calcium Spikes Play a Crucial Role in Symbiotic Signaling

3.5. Cytokinins and Auxins

3.6. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

4. Effects of N Fertilizer on Rhizobial Motility

5. Effect of N Fertilizer on Root-Hair Curling, Infection Thread Formation and Nodulation

6. Effect of Nitrogen Fertilizers on Nodule Physiology

6.1. Nodule Nitrate Reductase

6.2. Leghemoglobin

6.3. Nitrogenase Activity

Studies have been conducted over several decades to understand the inhibition of nitrogen fixation by mineral nitrogen. This is of increasing importance as environmentalists and agricultural scientists seek ways to reduce fertilizer use in field crops. If we can manipulate symbiosis to overcome this inhibition, legumes could increase the amount of nitrogen derived from nitrogen fixation, which would have a greater impact on soil nitrogen levels. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the mechanism of nitrate inhibition of nitrogenase activity in legumes. These include changes in plant carbohydrate distribution, resulting in energy and carbon deficiencies in nodules [158], inhibition of nitrogenase or leghemoglobin synthesis [159][160], inhibition of nitrogenase or leghemoglobin activity by nitrite [161][162], and inhibition of nitrogenase activity by the products of nitrogen fixation [163]. These factors include exposure of nodulated roots to nitrate [164][165][166]. Understanding these mechanisms is important for reducing crop fertilization and increasing the amount of plant nitrogen from nitrogen fixation. Inhibition of leghemoglobin synthesis and ammonia assimilating enzymes in nodules has been found to contribute to this process [167]. It has been determined that the decrease in nitrogenase activity in peas exposed to ammonium nitrate is attributed to a decline in leghemoglobin synthesis [160].

7. Mitigation Strategies

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agriculture13112092

References

- Bernhard, A. The nitrogen cycle: Processes, players, and human impact. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2010, 3, 25.

- Habete, A.; Buraka, T. Effect of Rhizobium inoculation and nitrogen fertilization on nodulation and yield response of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaries L.) at Boloso Sore, Southern Ethiopia. J. Biol. Agric. Health 2016, 6, 72–75.

- Aboelfadel, M.; Hassan, G.; Taha, M.A. Impact of Nitrogen Fertilization Types on Leaf Miner, Liriomyza trifolii Infestation, Growth and Productivity of Pea Plants under Pest Control Program. J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2023, 28, 92–105.

- Vance, C.P. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and phosphorus acquisition. Plant nutrition in a world of declining renewable resources. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 390–397.

- Menegat, S.; Ledo, A.; Tirado, R. Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14490.

- Rosa, L.; Rulli, M.C.; Ali, S.; Chiarelli, D.D.; Dell’Angelo, J.; Mueller, N.D.; Scheidel, A.; Siciliano, G.; D’Odorico, P. Energy implications of the 21st century agrarian transition. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2319.

- Tilman, D. Global environmental impacts of agricultural expansion: The need for sustainable and efficient practices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5995–6000.

- Ghavam, S.; Vahdati, M.; Wilson, I.A.G.; Styring, P. Sustainable Ammonia Production Processes. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9.

- IFA. Energy Efficiency and CO2 Emissions in Ammonia Production. 2009. Available online: https://www.fertilizer.org/images/Library_Downloads/2009_IFA_energy_efficiency.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- Zhang, W.-F.; Dou, Z.-X.; He, P.; Ju, X.-T.; Powlson, D.; Chadwick, D.; Norse, D.; Lu, Y.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; et al. New technologies reduce greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogenous fertilizer in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8375–8380.

- Brentrup, F.; Hoxha, A.; Christensen, B. Carbon footprint analysis of mineral fertilizer production in Europe and other world regions. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment of Food (LCA Food 2016), Dublin, Ireland, 19–21 October 2016.

- Wood, S.; Cowie, A. A review of greenhouse gas emission factors for fertilizer production. IEA Bioenergy Task 2004, 38, 1–20.

- Snyder, C.; Bruulsema, T.; Jensen, T.; Fixen, P. Review of greenhouse gas emissions from crop production systems and fertilizer management effects. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 133, 247–266.

- Taheripour, F.; Zhao, X.; Tyner, W.E. The impact of considering land intensification and updated data on biofuels land use change and emissions estimates. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 191.

- Statista 2023. Global Consumption of Agricultural Fertilizer from 1965 to 2020, by Nutrient (In Million Metric Tons). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/438967/fertilizer-consumption-globally-by-nutrient/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Woods, J.; Williams, A.; Hughes, J.K.; Black, M.; Murphy, R. Energy and the food system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2991–3006.

- Gellings, C.W.; Parmenter, K.E. Energy Efficiency in Fertilizer Production and Use. Efficient Use and Conservation of Energy. In Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems; Gellings, C.W., Ed.; EPRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 123–136.

- Camargo, J.A.; Alonso, Á. Ecological and toxicological effects of inorganic nitrogen pollution in aquatic ecosystems: A global assessment. Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 831–849.

- Khan, M.N.; Mobin, M.; Abbas, Z.K.; Alamri, S.A. Fertilizers and their contaminants in soils, surface, and groundwater. Encycl. Anthr. 2018, 5, 225–240.

- Zheng, M.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, P.; Mo, J. Global pattern and controls of biological nitrogen fixation under nutrient en-richment: A meta-analysis. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2019, 25, 3018–3030.

- Singh, B. Are Nitrogen Fertil. Deleterious Soil Health? Agronomy 2018, 8, 48.

- Sainju, U.M.; Ghimire, R.; Pradhan, G.P. Nitrogen Fertilization I: Impact on Crop, Soil, and Environment. In Nitrogen Fixation, Biochemistry; Rigobelo, R.C., Serra, A.B., Eds.; Intech Open Book: London, UK, 2019; Volume 11, pp. 69–92.

- Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Ao, G.; Qin, W.; Han, M.; Shen, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, B. Globally nitrogen addition alters soil microbial community structure, but has minor effects on soil microbial diversity and richness. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 179, 108982.

- Sud, M. Managing the Biodiversity Impacts of Fertilizer and Pesticide Use: Overview and Insights from Trends and Policies across Selected OECD Countries; OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 155; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020.

- Ouikhalfan, M.; Lakbita, O.; Delhali, A.; Assen, A.H.; Belmabkhout, Y. Toward Net-Zero Emission Fertilizers Industry: Greenhouse Gas Emission Analyses and Decarbonization Solutions. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 4198–4223.

- Aggani, S.L. Development of bio-fertilizers and its future perspective. Sch. Acad. J. Pharm. 2013, 2, 327–332.

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.-H.; Ye, C.; Zhou, W.; Cai, Z.-C.; Yang, H.; Han, X. Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition Associated with the Eutrophication of Taihu Lake. J. Chem. 2018, 2018, 4017107.

- Herridge, D.F. Inoculation Technology for Legumes. In Nitrogen-Fixing Leguminous Symbioses (77–115); Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008.

- Galloway, J.N.; Townsend, A.R.; Erisman, J.W.; Bekunda, M.; Cai, Z.; Freney, J.R.; Martinelli, L.A.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Sutton, M.A. Transformation of the Nitrogen Cycle: Recent Trends, Questions, and Potential Solutions. Science 2008, 320, 889–892.

- Davies-Barnard, T.; Friedlingstein, P.; Zaehle, S.; Bovkin, V.; Fan, Y.; Fisher, R.; Lee, H.; Peano, D.; Smith, B.; Warlind, D.; et al. Evaluating Terrestrial Biological Nitrogen Fixation in CMIP6 Earth System Models. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. B024-04.

- Boddey, R.M.; Jantalia, C.P.; Conceiãão, P.C.; Zanatta, J.A.; Bayer, C.; Mielniczuk, J.; Dieckow, J.; DOS Santos, H.P.; Denardin, J.E.; Aita, C.; et al. Carbon accumulation at depth in Ferralsols under zero-till subtropical agriculture. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2010, 16, 784–795.

- Unkovich, M.J.; Herridge, D.F.; Denton, M.D.; McDonald, G.K.; McNeill, A.M.; Long, W.; Farquharson, R.; Malcolm, B. A Nitrogen Reference Manual for the Southern Cropping Region; Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC): Canberra, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1959.11/31716 (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Sprent, J.I.; Sprent, P. Nitrogen Fixing Organisms: Pure and Applied Aspects; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1990; Volume 256.

- Whitman, W.B.; Coleman, D.C.; Wiebe, W.J. Prokaryotes: The unseen majority. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6578–6583.

- Brock, T.D.; Madigan, M.T.; Martinko, J.M.; Parker, J. Brock Biology of Microorganisms; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003.

- Bodenhausen, N.; Horton, M.W.; Bergelson, J. Bacterial communities associated with the leaves and the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 2013, 9, e56329.

- Dong, C.-J.; Wang, L.-L.; Li, Q.; Shang, Q.-M. Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere, phyllosphere and endosphere of tomato plants. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223847.

- Santi, C.; Bogusz, D.; Franche, C. Biological nitrogen fixation in non-legume plants. Ann. Bot. 2013, 111, 743–767.

- Geddes, B.A.; Oresnik, I.J. The Mechanism of Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation. In The Mechanistic Benefits of Microbial Symbionts; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2016; pp. 69–97.

- Soumare, A.; Diedhiou, A.G.; Thuita, M.; Hafidi, M.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Kouisni, L. Exploiting Biological Nitrogen Fixation: A Route Towards a Sustainable Agriculture. Plants 2020, 9, 1011.

- Coba de la Pena, T.; Fedorova, E.; Pueyo, J.J.; Lucas, M.M. The symbiosome: Legume and rhizobia co-evolution toward a nitrogen-fixing organelle? Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 8, 2229.

- Sprent, J.I.; Gehlot, H.S. Nodulated legumes in arid and semi-arid environments: Are they important? Plant Ecol. Divers. 2010, 3, 211–219.

- Kebede, E. Contribution, Utilization, and Improvement of Legumes-Driven Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Agricultural Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 767998.

- Fahde, S.; Boughribil, S.; Sijilmassi, B.; Amri, A. Rhizobia: A Promising Source of Plant Growth-Promoting Molecules and Their Non-Legume Interactions: Examining Applications and Mechanisms. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1279.

- Mng’Ong’O, M.E.; Ojija, F.; Aloo, B.N. The role of Rhizobia toward food production, food and soil security through microbial agro-input utilization in developing countries. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100404.

- Abd-Alla, M.H.; Bagy, M.K.; El-enany, A.W.E.S.; Bashandy, S.R. Activation of Rhizobium tibeticum with flavonoids en-hances nodulation, nitrogen fixation, and growth of fenugreek (Trigonella foenumgraecum L.) grown in cobalt-polluted soil. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 66, 303–315.

- Abd-Alla, M.H.; Issa, A.A.; Ohyama, T. Impact of harsh environmental conditions on nodule formation and dinitrogen fixation of legumes. Adv. Biol. Ecol. Nitrogen Fixat. 2014, 9, 1.

- Abd-Alla, M.H.; Nafady, N.A.; Bashandy, S.R.; Hassan, A.A. Mitigation of effect of salt stress on the nodulation, nitrogen fixation and growth of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) by triple microbial inoculation. Rhizosphere 2019, 10, 100148.

- Abd-Alla, M.H.; Wahab, A.A. Survival of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viceae subjected to heat, drought, and salinity in soil. Biol. Plant. 1995, 37, 131–137.

- Wahab, A.M.A.; Zahran, H.H.; Abd-Alla, M.H. Root-hair infection and nodulation of four grain legumes as affected by the form and the application time of nitrogen fertilizer. Folia Microbiol. 1996, 41, 303–308.

- Abdel Wahab, A.M.; Abd-Alla, M.H. Effect of different rates of N-fertilizers on nodulation, nodule activities and growth of two field grown cvs. of soybean. In Fertilizers and Environment, Proceedings of the International Symposium “Fertilizers and Environment”, Salamanca, Spain, 26–29 September 1994; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 89–93.

- Abdel Wahab, A.; Mand Abd-Alla, M.H. Nodulation and nitrogenase activity of Vicia faba and Glycine max in relation to rhizobia strain, form and level of combined nitrogen. Phyton 1995, 35, 77–187.

- Wahab, A.M.A.; Abd-Alla, M.H. Effect of form and level of applied nitrogen on nitrogenase and nitrate reductase activities in faba beans. Biol. Plant. 1995, 37, 57–64.

- Abdel Wahab, A.M.; Abd-Alla, M.H. Effect of combined nitrogen on the structure of N2-fixing nodules in two legumes. In Nitrogen Fixation: Hundred Years after; Gustav Fischer Stuttgart: New York, NY, USA, 1988; Volume 535.

- Singla, P.; Garg, N. Plant flavonoids: Key players in signaling, establishment, and regulation of rhizobial and mycorrhizal endosymbioses. In Mycorrhiza-Function, Diversity, State of the Art; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 133–176.

- Bag, S.; Mondal, A.; Majumder, A.; Mondal, S.K.; Banik, A. Flavonoid mediated selective crosstalk between plants and beneficial soil microbiome. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1739–1760.

- Massalha, H.; Korenblum, E.; Tholl, D.; Aharoni, A. Small molecules below-ground: The role of specialized metabolites in the rhizosphere. Plant J. 2017, 90, 788–807.

- Lone, R.; Baba, S.H.; Khan, S.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Kamili, A.N. Phenolics: Key Players in Interaction between Plants and Their Environment. In Plant Phenolics in Abiotic Stress Management (23–46); Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023.

- Dong, N.Q.; Lin, H.X. Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant–environment interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209.

- Dong, W.; Song, Y. The Significance of Flavonoids in the Process of Biological Nitrogen Fixation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5926.

- Abd-Alla, M.H. Regulation of nodule formation in soybean-Bradyrhizobium symbiosis is controlled by shoot or/and root sig-nals. Plant Growth Regul. 2001, 34, 241–250.

- Yokota, K.; Fukai, E.; Madsen, L.H.; Jurkiewicz, A.; Rueda, P.; Radutoiu, S.; Held, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Szczyglowski, K.; Morieri, G.; et al. Rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton mediates invasion of Lotus japonicus roots by Mesorhizobium loti. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 267–284.

- Mergaert, P.; Kereszt, A.; Kondorosi, E. Gene Expression in Nitrogen-Fixing Symbiotic Nodule Cells in Medicago truncatula and Other Nodulating Plants. Plant Cell 2019, 32, 42–68.

- Munoz Aguilar, J.M.; Ashby, A.M.; Richards, A.J.; Loake, G.J.; Watson, M.D.; Shaw, C.H. Chemotaxis of Rhizobium le-guminosarum biovar phaseoli towards flavonoid inducers of the symbiotic nodulation genes. Microbiology 1988, 134, 2741–2746.

- Abdel-Lateif, K.; Bogusz, D.; Hocher, V. The role of flavonoids in the establishment of plant roots nodule symbiosiss with arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi, rhizobia and Frankia bacteria. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 636–641.

- Fournier, J.; Teillet, A.; Chabaud, M.; Ivanov, S.; Genre, A.; Limpens, E.; de Carvalho-Niebel, F.; Barker, D.G. Re-modeling of the infection chamber before infection thread formation reveals a two-step mechanism for rhizobial entry into the host legume root hair. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1233–1242.

- Fournier, J.; Timmers, A.C.; Sieberer, B.J.; Jauneau, A.; Chabaud, M.; Barker, D.G. Mechanism of infection thread elongation in root hairs of Medicago truncatula and dynamic interplay with associated rhizobial colonization. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1985–1995.

- Oldroyd, G.E.; Downie, J.A. Coordinating Nodule Morphogenesis with Rhizobial Infection in Legumes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 519–546.

- Yang, J.; Lan, L.; Jin, Y.; Yu, N.; Wang, D.; Wang, E. Mechanisms underlying legume–Rhizobium symbioses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 64, 244–267.

- Suzaki, T.; Yoro, E.; Kawaguchi, M. Leguminous plants: Inventors of root nodules to accommodate symbiotic bacteria. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 316, 111–158.

- Jones, K.M.; Kobayashi, H.; Davies, B.W.; Taga, M.E.; Walker, G.C. How rhizobial symbionts invade plants: The Si-norhizobium–Medicago model. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 619–633.

- Catoira, R.; Galera, C.; de Billy, F.; Penmetsa, R.V.; Journet, E.P.; Maillet, F.; Rosenberg, C.; Cook, D.; Gough, C.; Dénarié, J. Four genes of Medicago truncatula controlling components of a Nod factor transduction pathway. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1647–1665.

- Barbulova, A.; Rogato, A.; Apuzzo, E.; Omrane, S.; Chiurazzi, M. Differential effects of combined N sources on early steps of the nod factor–dependent transduction pathway in Lotus japonicus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 994–1003.

- Patra, D.; Mandal, S. Nod–factors are dispensable for nodulation: A twist in bradyrhizobia-legume symbiosis. Symbiosis 2022, 86, 1–15.

- Calderón-Flores, A.; Du Pont, G.; Huerta-Saquero, A.; Merchant-Larios, H.; Servín-González, L.; Durán, S. The Stringent Response Is Required for Amino Acid and Nitrate Utilization, Nod Factor Regulation, Nodulation, and Nitrogen Fixation in Rhizobium etli. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 5075–5083.

- Endre, G.; Kereszt, A.; Kevei, Z.; Mihacea, S.; Kaló, P.; Kiss, G.B. A receptor kinase gene regulating symbiotic nodule development. Nature 2002, 417, 962–966.

- Nguyen, T.H.N.; Brechenmacher, L.; Aldrich, J.T.; Clauss, T.R.; Gritsenko, M.A.; Hixson, K.K.; Libault, M.; Tanaka, K.; Yang, F.; Yao, Q.; et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of soybean root hairs inoculated with Brady-rhizobium japonicum. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012, 11, 1140–1155.

- Esseling, J.J.; Lhuissier, F.G.; Emons, A.M.C. A Nonsymbiotic Root Hair Tip Growth Phenotype in NORK-Mutated Legumes: Implications for Nodulation Factor–Induced Signaling and Formation of a Multifaceted Root Hair Pocket for Bacteria. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 933–944.

- Popp, C.; Ott, T. Regulation of signal transduction and bacterial infection during root nodule symbiosis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 458–467.

- Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Sang, T.; Wang, P.; Dai, S.; Zhang, S.; Meng, X. Differential phosphorylation of the transcription factor WRKY33 by the protein kinases CPK5/CPK6 and MPK3/MPK6 cooperatively regulates camalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 2621–2638.

- Wang, L.; Deng, L.; Bai, X.; Jiao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Y. Regulation of nodule number by GmNORK is dependent on expression of GmNIC in soybean. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 94, 221–230.

- Oldroyd, G.E.; Downie, J.A. Calcium, kinases and nodulation signaling in legumes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 566–576.

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Shao, J.; Liu, Y.; Xuan, W.; Xu, G.; Zhang, R. Signal communication during microbial modulation of root-system architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, erad263.

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, M.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, C.; Du, B.; Xu, D.; Li, L. Signal Molecules Regulate the Synthesis of Secondary Metabolites in the Interaction between Endophytes and Medicinal Plants. Processes 2023, 11, 849.

- Tian, W.; Wang, C.; Gao, Q.; Li, L.; Luan, S. Calcium spikes, waves and oscillations in plant development and biotic interactions. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 750–759.

- Svistoonoff, S.; Hocher, V.; Gherbi, H. Actinorhizal root nodule symbioses: What is signalling telling on the origins of nodulation? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 20, 11–18.

- DeFalco, T.A.; Bender, K.W.; Snedden, W.A. Breaking the code: Ca2+ sensors in plant signalling. Biochem. J. 2009, 425, 27–40.

- de Billy, F.; Grosjean, C.; May, S.; Bennett, M.; Cullimore, J.V. Expression studies on AUX1-like genes in Medicago truncatula suggest that auxin is required at two steps in early nodule development. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2001, 14, 267–277.

- Ryu, H.; Cho, H.; Choi, D.; Hwang, I. Plant hormonal regulation of nitrogen-fixing nodule organogenesis. Mol. Cells 2012, 34, 117–126.

- Nagata, M.; Suzuki, A. Effects of phytohormones on nodulation and nitrogen fixation in leguminous plants. In Advances In Biology and Ecology of Nitrogen Fixation; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2014; pp. 111–128.

- Gamas, P.; Brault, M.; Jardinaud, M.-F.; Frugier, F. Cytokinins in Symbiotic Nodulation: When, Where, What For? Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 792–802.

- Reid, D.; Nadzieja, M.; Novák, O.; Heckmann, A.B.; Sandal, N.; Stougaard, J. Cytokinin Biosynthesis Promotes Cortical Cell Responses during Nodule Development. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 361–375.

- Mohd-Radzman, N.A.; Djordjevic, M.A.; Imin, N. Nitrogen modulation of legume root architecture signaling pathways involves phytohormones and small regulatory molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 385.

- Miri, M.; Janakirama, P.; Held, M.; Ross, L.; Szczyglowski, K. Into the Root: How Cytokinin Controls Rhizobial Infection. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 21, 178–186.

- Reid, D.E.; Heckmann, A.B.; Novák, O.; Kelly, S.; Stougaard, J. Cytokinin Oxidase/Dehydrogenase3 Maintains Cytokinin Homeostasis during Root and Nodule Development in Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol. 2015, 170, 1060–1074.

- Gupta, R.; Anand, G.; Bar, M. Developmental Phytohormones: Key Players in Host-Microbe Interactions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 1–22.

- Becana, M.; Dalton, D.A.; Moran, J.F.; Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I.; Matamoros, M.A.; Rubio, M.C. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in legume nodules. Physiol. Plant. 2000, 109, 372–381.

- Pauly, N.; Pucciariello, C.; Mandon, K.; Innocenti, G.; Jamet, A.; Baudouin, E.; Hérouart, D.; Frendo, P.; Puppo, A. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and glutathione: Key players in the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 1769–1776.

- Minchin, F.R.; James, E.K.; Becana, M. Oxygen diffusion, production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, and antioxidants in legume nodules. Nitrogen-Fixing Legum. Symbioses 2008, 7, 321–362.

- Nanda, A.K.; Andrio, E.; Marino, D.; Pauly, N.; Dunand, C. Reactive Oxygen Species during Plant-microorganism Early Interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 195–204.

- Hérouart, D.; Baudouin, E.; Frendo, P.; Harrison, J.; Santos, R.; Jamet, A.; Van de Sype, G.; Touati, D.; Puppo, A. Reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide and glutathione: A key role in the establishment of the legume–Rhizobium symbiosis? Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 40, 619–624.

- Peleg-Grossman, S.; Volpin, H.; Levine, A. Root hair curling and Rhizobium infection in Medicago truncatula are mediated by phosphatidylinositide-regulated endocytosis and reactive oxygen species. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1637–1649.

- Lohar, D.P.; Haridas, S.; Gantt, J.S.; VandenBosch, K.A. A transient decrease in reactive oxygen species in roots leads to root hair deformation in the legume–rhizobia symbiosis. New Phytol. 2006, 173, 39–49.

- Minguillón, S.; Matamoros, M.A.; Duanmu, D.; Becana, M. Signaling by reactive molecules and antioxidants in legume nodules. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 815–832.

- Mandal, M.; Sarkar, M.; Khan, A.; Biswas, M.; Masi, A.; Rakwal, R.; Agrawal, G.K.; Srivastava, A.; Sarkar, A. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) in plants– maintenance of structural individuality and functional blend. Adv. Redox Res. 2022, 5, 100039.

- Tsyganova, A.V.; Brewin, N.J.; Tsyganov, V.E. Structure and Development of the Legume-Rhizobial Symbiotic Interface in Infection Threads. Cells 2021, 10, 1050.

- Mazars, C.; Thuleau, P.; Lamotte, O.; Bourque, S. Cross-Talk between ROS and Calcium in Regulation of Nuclear Activities. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 706–718.

- Khan, M.; Ali, S.; Al Azzawi, T.N.I.; Saqib, S.; Ullah, F.; Ayaz, A.; Zaman, W. The Key Roles of ROS and RNS as a Signaling Molecule in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 268.

- Lecona, A.M.; Nanjareddy, K.; Blanco, L.; Piazza, V.; Vera-Núñez, J.A.; Lara, M.; Arthikala, M.-K. CRK12: A Key Player in Regulating the Phaseolus vulgaris-Rhizobium tropici Symbiotic Interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11720.

- Abeed, A.H.; Saleem, M.H.; Asghar, M.A.; Mumtaz, S.; Ameer, A.; Ali, B.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Elshikh, M.S.; Ercisli, S.; El-sharkawy, M.M.; et al. Ameliorative Effects of Exogenous Potassium Nitrate on Antioxidant Defense System and Mineral Nutrient Uptake in Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) under Salinity Stress. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 22575–22588.

- Weese, D.J.; Heath, K.D.; Dentinger, B.T.M.; Lau, J.A. Long-term nitrogen addition causes the evolution of less-cooperative mutualists. Evolution 2015, 69, 631–642.

- Aroney, S.T.N.; Poole, P.S.; Sánchez-Cañizares, C. Rhizobial Chemotaxis and Motility Systems at Work in the Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 725338.

- Fernandes, C.; Ravi, L. Screening of symbiotic ability of Rhizobium under hydroponic conditions. In Microbial Symbionts; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 327–341.

- Lindström, K.; Mousavi, S.A. Effectiveness of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 13, 1314–1335.

- Oono, R.; Muller, K.E.; Ho, R.; Jimenez Salinas, A.; Denison, R.F. How do less-expensive nitrogen alternatives affect legume sanctions on rhizobia? Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 10645–10656.

- Burghardt, L.T.; Epstein, B.; Hoge, M.; Trujillo, D.I.; Tiffin, P. Host-Associated Rhizobial Fitness: Dependence on Nitrogen, Density, Community Complexity, and Legume Genotype. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0052622.

- Wendlandt, C.E.; Gano-Cohen, K.A.; Stokes, P.J.N.; Jonnala, B.N.R.; Zomorrodian, A.J.; Al-Moussawi, K.; Sachs, J.L. Wild legumes maintain beneficial soil rhizobia populations despite decades of nitrogen deposition. Oecologia 2022, 198, 419–430.

- Godschalx, A.L.; Diethelm, A.C.; Kautz, S.; Ballhorn, D.J. Nitrogen-Fixing Rhizobia Affect Multitrophic Interactions in the Field. J. Insect Behav. 2023, 36, 168–179.

- Brito-Santana, P.; Duque-Pedraza, J.J.; Bernabéu-Roda, L.M.; Carvia-Hermoso, C.; Cuéllar, V.; Fuentes-Romero, F.; Acosta-Jurado, S.; Vinardell, J.M.; Soto, M.J. Sinorhizobium meliloti DnaJ Is Required for Surface Motility, Stress Tolerance, and for Efficient Nodulation and Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5848.

- Ohyama, T.; Ikebe, K.; Okuoka, S.; Ozawa, T.; Nishiura, T.; Ishiwata, T.; Yamazaki, A.; Tanaka, F.; Takahashi, T.; Umezawa, T.; et al. A deep placement of lime nitrogen reduces the nitrate leaching and promotes soybean growth and seed yield. Crop. Environ. 2022, 1, 221–230.

- Ohyama, T.; Takayama, K.; Akagi, A.; Saito, A.; Higuchi, K.; Sato, T. Development of an N-Free Culture Solution for Cultivation of Nodulated Soybean with Less pH Fluctuation by the Addition of Potassium Bicarbonate. Agriculture 2023, 13, 739.

- Tambalo, D.D.; Yost, C.K.; Hynes, M.F. Motility and chemotaxis in the rhizobia. In Biological Nitrogen Fixation; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 337–348.

- Raina, J.-B.; Fernandez, V.; Lambert, B.; Stocker, R.; Seymour, J.R. The role of microbial motility and chemotaxis in symbiosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 284–294.

- Sandhu, A.K.; Brown, M.R.; Subramanian, S.; Brözel, V.S. Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens USDA 110 displays plasticity in the attachment phenotype when grown in different soybean root exudate compounds. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1190396.

- Tham, I.; Tham, F.Y. Effects of nitrogen on nodulation and promiscuity in the Acacia mangium rhizobia relationship. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2007, 6, 941–948.

- Ohyama, T.; Fujikake, H.; Yashima, H.; Tanabata, S.; Ishikawa, S.; Sato, T.; Nishiwaki, T.; Ohtake, N.; Sueyoshi, K.; Ishii, S.; et al. Effect of nitrate on nodulation and nitrogen fixation of soybean. Soybean Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 10, 333–364.

- Saito, A.; Tanabata, S.; Tanabata, T.; Tajima, S.; Ueno, M.; Ishikawa, S.; Ohtake, N.; Sueyoshi, K.; Ohyama, T. Effect of Nitrate on Nodule and Root Growth of Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 4464–4480.

- Herliana, O.; Harjoso, T.; Anwar, A.H.S.; Fauzi, A. The effect of Rhizobium and N fertilizer on growth and yield of black soybean (Glycine max (L) Merril). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 255, p. 012015.

- Garg, N.; Geetanjali. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation in legume nodules: Process and signaling: A review. In Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 519–531.

- Mendoza-Suárez, M.; Andersen, S.U.; Poole, P.S.; Sánchez-Cañizares, C. Competition, Nodule Occupancy, and Persistence of Inoculant Strains: Key Factors in the Rhizobium-Legume Symbioses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 690567.

- Murray, J.D. Invasion by Invitation: Rhizobial Infection in Legumes. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 631–639.

- Nishida, H.; Suzaki, T. Nitrate-mediated control of root nodule symbiosis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 44, 129–136.

- Ferguson, B.J.; Indrasumunar, A.; Hayashi, S.; Lin, M.-H.; Lin, Y.-H.; Reid, D.E.; Gresshoff, P.M. Molecular Analysis of Legume Nodule Development and Autoregulation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 61–76.

- Akter, Z.; Lupwayi, N.Z.; Balasubramanian, P. Nitrogen use efficiency of irrigated dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes in southern Alberta. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 97, 610–619.

- Akter, Z.; Pageni, B.B.; Lupwayi, N.Z.; Balasubramanian, P.M. Biological nitrogen fixation by irrigated dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2018, 98, 1159–1167.

- Reinprecht, Y.; Schram, L.; Marsolais, F.; Smith, T.H.; Hill, B.; Pauls, K.P. Effects of Nitrogen Application on Nitrogen Fixation in Common Bean Production. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 534817.

- Karmarkar, V. Transcriptional Regulation of Nodule Development and Senescence in Medicago Truncatula; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014.

- Farid, M.; Earl, H.J.; Navabi, A. Yield Stability of Dry Bean Genotypes across Nitrogen-Fixation-Dependent and Fertilizer-Dependent Management Systems. Crop. Sci. 2016, 56, 173–182.

- Franck, S.; Strodtman, K.N.; Qiu, J.; Emerich, D.W. Transcriptomic Characterization of Bradyrhizobium diaz-oefficiens Bacteroids Reveals a Post-Symbiotic, Hemibiotrophic-Like Lifestyle of the Bacteria within Senescing Soybean Nodules. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3918.

- Strodtman, K.N.; Frank, S.; Stevenson, S.; Thelen, J.J.; Emerich, D.W. Proteomic characterization of Bradyrhi-zobium diazoefficiens bacteroids reveals a post-symbiotic, hemibiotrophic-like lifestyle of the bacteria within senescing soybean nodules. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3947.

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, X. Characteristics and Research Progress of Legume Nodule Senescence. Plants 2021, 10, 1103.

- Ono, Y.; Fukasawa, M.; Sueyoshi, K.; Ohtake, N.; Sato, T.; Tanabata, S.; Toyota, R.; Higuchi, K.; Saito, A.; Ohyama, T. Application of nitrate, ammonium, or urea changes the concentrations of ureides, urea, amino acids and other metabolites in xylem sap and in the organs of soybean plants (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4573.

- Li, S.; Wu, C.; Liu, H.; Lyu, X.; Xiao, F.; Zhao, S.; Ma, C.; Yan, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Systemic regulation of nodule structure and assimilated carbon distribution by nitrate in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1101074.

- Martensson, A.M.; Brutti, L.; Ljunggren, H. Competition between strains of Bradyrhizobium japonicum for nod-ulation of soybeans at different nitrogen fertilizer levels. Plant Soil 1989, 117, 219–225.

- Jiang, Y.; MacLean, D.E.; Perry, G.E.; Marsolais, F.; Hill, B.; Pauls, K.P. Evaluation of beneficial and inhibitory effects of nitrate on nodulation and nitrogen fixation in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Legum. Sci. 2020, 2, e45.

- Cheniae, G.; Evans, H.J. Physiological Studies on Nodule-Nitrate Reductase. Plant Physiol. 1960, 35, 454–462.

- Gibson, A.H.; Pagan, J.D. Nitrate effects on the nodulation of legumes inoculated with nitrate-reductase-deficient mutants of Rhizobium. Planta 1977, 134, 17–22.

- Manhart, J.R.; Wong, P.P. Nitrate effect on nitrogen fixation (acetylene reduction) activities of legume root nodules induced by rhizobia with varied nitrate reductase activities. Plant Physiol. 1980, 65, 502–505.

- Streeter, J.G. Synthesis and Accumulation of Nitrite in Soybean Nodules Supplied with Nitrate. Plant Physiol. 1982, 69, 1429–1434.

- Stephens, B.D.; Neyra, C.A. Nitrate and Nitrite Reduction in Relation to Nitrogenase Activity in Soybean Nodules and Rhizobium japonicum Bacteroids. Plant Physiol. 1983, 71, 731–735.

- Kubo, H. Uber hamoprotein aus den wurzelknollchen von leguminosen. Acta Phytochimica 1939, 11, 195–200.

- Keilin, D.; Wang, Y.L. Haemoglobin of Gastrophilus larvae. Purification and properties. Biochem. J. 1946, 40, 855.

- Virtanen, A.I.; Laine, T. Red, Brown and Green Pigments in Leguminous Root Nodules. Nature 1946, 157, 25–26.

- Wittenberg, J.B.; Bergersen, F.J.; Appleby, C.A.; Turner, G.L. Facilitated oxygen diffusion: The role of leghemo-globin in nitrogen fixation by bacteroids isolated from soybean root nodules. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 4057–4066.

- Appleby, C.A. The origin and functions of haemoglobin in plants. Sci. Prog. 1933, 76, 365–398.

- Appleby, C.A.; Tjepkema, J.D.; Trinick, M.J. Hemoglobin in a non-leguminous plant, Parasponia: Possible genetic origin and function in nitrogen fixation. Science 1983, 220, 951–953.

- Silvester, W.B.; Berg, R.H.; Schwintzer, C.R.; Tjepkema, J.D. Oxygen responses, hemoglobin, and the structure and function of vesicles. In Nitrogen-Fixing Actinorhizal Symbioses; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 105–146.

- Latimore, M., Jr.; Giddens, J.; Ashley, D.A. Effect of Ammonium and Nitrate Nitrogen upon Photosynthate Supply and Nitrogen Fixation by Soybeans 1. Crop Sci. 1977, 17, 399–404.

- Roberts, G.P.; Brill, W.J. Genetics and Regulation of Nitrogen Fixation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1981, 35, 207–235.

- Bisseling, T.; Bos, R.V.D.; Van Kammen, A. The effect of ammonium nitrate on the synthesis of nitrogenase and the concentration of leghemoglobin in pea root nodules induced by Rhizobium leguminosarum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 1978, 539, 1–11.

- Rigaud, J.; Puppo, A. Effect of nitrite upon leghemoglobin and interaction with nitrogen fixation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 1977, 497, 702–706.

- Trinchant, J.C.; Rigaud, J. Nitrogen fixation in French-beans in the presence of nitrate: Effect on bacteroid res-piration and comparison with nitrite. J. Plant Physiol. 1984, 116, 209–217.

- Schuller, K.A.; Day, D.A.; Gibson, A.H.; Gresshoff, P.M. Enzymes of ammonia assimilation and ureide biosynthesis in soybean nodules: Effect of nitrate. Plant Physiol. 1986, 80, 646–650.

- Schuller, K.A.; Minchin, F.R.; Gresshoff, P.M. Nitrogenase Activity and Oxygen Diffusion in Nodules of Soyabean cv. Bragg and a Supernodulating Mutant: Effects of Nitrate. J. Exp. Bot. 1988, 39, 865–877.

- Vessey, J.K.; Walsh, K.B.; Layzell, D.B. Oxygen limitation of N2 fixation in stem-girdled and nitrate-treated soybean. Physiol. Plant. 1988, 73, 113–121.

- Vessey, J.K.; Walsh, K.B.; Layzell, D.B. Can a limitation in phloem supply to nodules account for the inhibitory effect of nitrate on nitrogenase activity in soybean? Physiol. Plant. 1988, 74, 137–146.

- Minchin, F.R.; Becana, M.; Sprent, J.I. Short-term inhibition of legume N 2 fixation by nitrate: II. Nitrate effects on nodule oxygen diffusion. Planta 1989, 180, 46–52.

- Jensen, E.S.; Peoples, M.B.; Boddey, R.M.; Gresshoff, P.M.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; JR Alves, B.; Morrison, M.J. Legumes for mitigation of climate change and the provision of feedstock for biofuels and biorefineries. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 329–364.

- Grover, M.; Yaadesh, S.; Jayasurya, A. Associative Nitrogen Fixers-Options for Mitigating Climate Change. In Bioinoculants: Biological Option for Mitigating Global Climate Change (217–237); Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023.

- Dubey, A.; Malla, M.A.; Khan, F.; Chowdhary, K.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.; Khare, P.K.; Khan, M.L. Soil microbiome: A key player for conservation of soil health under changing climate. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 2405–2429.

- Mukhtar, H.; Wunderlich, R.F.; Muzaffar, A.; Ansari, A.; Shipin, O.V.; Cao, T.N.-D.; Lin, Y.-P. Soil microbiome feedback to climate change and options for mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 882, 163412.

- Jena, J.; Maitra, S.; Hossain, A.; Pramanick, B.; Gitari, H.I.; Praharaj, S.; Shankar, T.; Palai, J.B.; Rathore, A.; Mandal, T.K.; et al. Role of Legumes in Cropping System for Soil Ecosystem Improvement. Ecosystem Services: Types, Management and Benefits; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 415.

- Choudhary, A.K.; Rajanna, G.A.; Kumar, A. Integrated Nutrient Management: An Integral Component of ICM Approach. In Integrated Crop Management Practices; ICAR: New Delhi, India, 2018; p. 33.

- Gurjar, R.; Tomar, D.; Singh, A.; Kumar, K. Integrated nutrient management and its effect on mungbean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek): A revisit. Pharma Innov. J. 2022, 11, 379–384.

- Tomar, D.; Bhatnagar, G.S. A review on integrated nutrient management and its effect on mung bean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek). Pharma Innov. J. 2022, 11, 685–691.

- Obando, M.; Correa-Galeote, D.; Castellano-Hinojosa, A.; Gualpa, J.; Hidalgo, A.; Alché, J.D.D.; Bedmar, E.; Cassán, F. Analysis of the denitrification pathway and greenhouse gases emissions in Bradyrhizobium sp. strains used as biofertilizers in South America. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 739–749.

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 35–46.

- Wong, W.S.; Morald, T.K.; Whiteley, A.S.; Nevill, P.G.; Trengove, R.D.; Yong, J.W.H.; Dixon, K.W.; Valliere, J.M.; Stevens, J.C.; Veneklaas, E.J. Microbial inoculation to improve plant performance in mine-waste substrates: A test using pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan). Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 33, 497–511.

- Castellano-Hinojosa, A.; Mora, C.; Strauss, S.L. Native Rhizobia Improve Plant Growth, Fix N2, and Reduce Greenhouse Emissions of Sunnhemp More than Commercial Rhizobia Inoculants in Florida Citrus Orchards. Plants 2022, 11, 3011.