Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Environmental Studies

Urbanization is a critical and profound transformation of land, industry, and population in modern society. Environmental pollution significantly impacts the urbanization process.

- environmental pollution

- urban scale

- residents’ health

- mediating effects

1. Introduction

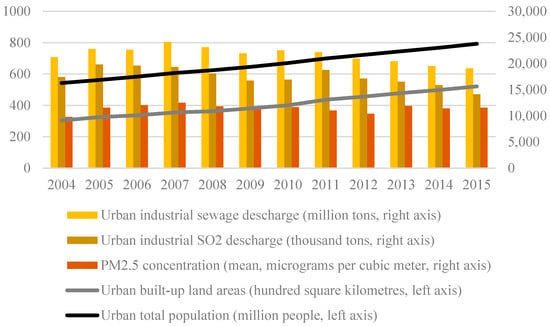

Urbanization is a critical and profound transformation of land, industry, and population in modern society [1]. During the complicated process of urbanization, rural factors are converted to urban factors, resulting in rural–urban migration and the expansion of existing cities [2]. China’s remarkable economic growth has been accompanied by an observable expansion in the urban scale, evident in both population migration and land use change (Figure 1). According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China [3], over the past two decades, China’s urban population has almost doubled, surging from 524 million to 921 million. Simultaneously, the total urban built-up area has also experienced a remarkable increase. This process has boosted economic growth by improving productivity and resulting in the agglomeration effect (or scale effect); however, it has also resulted in growing environmental pollution and health risks. Figure 1 illustrates that urban industrial pollutant emissions, particularly PM2.5 (PM2.5, or particulate matter 2.5, refers to tiny particles or droplets in the air that are two and one half microns or less in width) concentrations, have not exhibited a significant and consistent reduction since 2004. Moreover, the negative influences of pollution on human health and the relevant interactions between them have been examined from the perspective of disease incidence or death rates [4,5,6,7]. For instance, the Lancet published a report revealing that outdoor air pollution in China caused 1.23 million premature deaths and 25 million years of life lost in the year 2010, making China one of the countries with the greatest burden of environmental diseases in the world [8].

Under these circumstances, environmental protection and relevant health risks have become the focus of policymakers and the public. Given these circumstances, a growing focus on high-quality urbanization and sustainable development calls for research into the nexus between urban scale, urban pollution, and residents’ health in the Chinese context. Additionally, plenty of research has discussed the ecological or environmental effect of urbanization, e.g., [9,10,11], while this study attempts to fill in the research gap by providing relatively new insights into the effect of environmental pollution on urbanization.

Figure 1. Evolution of urban scale and urban pollution discharge in China (2004–2015). Sources: China Statistical Yearbook [3], China City Statistical Yearbook [12], and Columbia University (the basic data are available at: https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/ accessed on 10 May 2023).

2. Urban Scale and Its Factors

The urban scale usually refers to the size of a city. It serves as an important indicator of urban development and urbanization. This measure is often based on both the total population of an urban area and the overall built-up area of the city [20,21,22,23,24]. Furthermore, the non-agricultural population proportion and urban population density are also used to depict the urban scale [20,25,26].

The process of urbanization involves the conversion of population, industry, and land use. Thus, the urban scale is affected by migration, production, and policy priorities that are generally associated with, or even result from, various factors related to economic growth, social development, and the natural environment. Owing to the complexity of the determinants, city size is considered the result of the optimal trade-off between positive and negative externalities, along with urban development [27]. Regarding the urban population scale, empirical evidence has shown that industrial agglomeration, public service supply, productivity, living amenities, land use efficiency, and financial development exert positive impacts on urbanization [28,29,30,31,32]. Conversely, increasing capital costs, high housing prices, migration friction, and capital efficiency inhibit urban population growth [28,30,33]. On the other hand, the effects of economic growth, population migration, globalization, land revenue, transport costs, and urban planning on the urban land scale have been examined [34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Interestingly, the critical role and profound impacts of institutional factors in China, including development strategy, migration policy, and urban policy, on urban growth and urbanization have been emphasized by Song and Zhang [41] and Zhong et al. [39].

3. Nexus between Pollution and the Urban Scale

A considerable amount of research has investigated the relationship between urban scale and urban environment, e.g., [9,10,11,18,21], although most of these studies have focused on the eco-effects of urban scale or urbanization. In general, the proximity and concentration of activities are not only preconditions for social interactions and economic efficiency but also the source of resource depletion, environmental damage, and human health problems [42,43,44]. As specified by the conventional IPAT and STIRPAT models (as York et al. [45] introduced, the IPAT model denotes the formula: I = f (P, A, T), which was first derived from the Ehrlich-Holdren/Commoner debate in the early 1970s to capture the human impact (I) on the environment as a function of population (P), affluence (A), and technology (T) and has been commonly used, particularly in the domain of environmental studies since then. Additionally, the STIRPAT model has been developed as an extension of the IPAT model, which represents the Stochastic Impacts by Regression on Population, Affluence, and Technology), the population is a key theoretical driving factor of pollutant emissions. By revisiting and extending these models, extensive research has been conducted to decompose the population term into population scale and population structure, and further introduce urban scale and urbanization into the theoretical framework for analyzing key drivers of pollutant emissions [15,16,17,46,47]. Empirically, Oke [48] highlighted that there is a positive correlation between population scale and urban heat islands. Moreover, the positive impacts and causal links between urban size and pollution levels have been verified by several studies [11,16,17,42,47,49,50,51].

Focusing on the land scale, Hien et al. [52] and Zhou et al. [53] analyzed the close and coupled relationship between urban land expansion and environmental pollution. The former revealed that patterns of pollution landscapes are characterized by concentric urban expansion around the city center, while the latter illustrated that continuous construction land expansion has little impact on PM2.5 concentrations. Moreover, Huang and Du [10] found a positive impact of urban land expansion on pollution, while Yu et al. [14] showed opposite results. Furthermore, following the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) theory, numerous studies have extensively examined and validated the nonlinear impact of urbanization on pollution, shedding light on the intricate decoupling relationship involved [45,54,55]. In short, despite the abundance of research on the environmental effects of urbanization, a consensus has not yet been reached.

In turn, the optimal urban scale has been previously discussed, and the role of the environment has been preliminarily investigated. For example, Capello and Camagni [42] suggested that urban residents experiencing environmental externalities (such as pollution and disasters) in their city area tended to relocate to the surrounding area. Wu et al. [56] used a multi-level index system along with threshold models and concluded that environmental pollution hindered China’s urbanization. In addition, many studies have claimed that environmental pollution is a contributing factor to emigration, e.g., [13] and [57,58,59,60]. Among these, Chen et al. [58] performed robust investigations into the significant effect of air pollution on migration and specified that independent changes in air pollution could reduce both floating migration inflows and population through net outmigration in China. Interestingly, Cao et al. [13], Chen et al. [58], and Liu et al. [61] found that well-educated people and high-income groups are more sensitive to pollution. In addition, Zhao et al. [62] confirmed that pollution would negatively affect migrants’ settlement intentions, which essentially echoes previous findings about the pollution-migration relationship. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that beyond the perspective of population scale, there has been little research on the effects of environmental pollution on urban land use or land scale.

4. Nexus between Pollution and Residents’ Health

As a negative externality of production, pollution is harmful to health status and leads to further healthcare costs or economic losses for residents. Recent studies have focused on the health effects of environmental pollution, primarily from two aspects: health level and health costs.

Health levels are often depicted as health damage or disease. The effects of air pollution on human health can be either acute or chronic and may affect several different systems and organs. Symptoms may include respiratory disease, heart disease, lung cancer, and chronic bronchitis and may aggravate pre-existing heart and lung disease or asthmatic attacks [63]. As a potential disease outcome, short-term and long-term exposure to pollution are both believed to be connected to premature mortality and reduced life expectancy. In other words, the health-related effects of pollution differ between long-term and short-term exposures. The mortality risk associated with pollution is generally estimated to be higher with long-term exposure due to the potential for larger and more persistent cumulative effects [64]. Additionally, the association and positive causal relations between exposures to various pollution and health risk or mortality have been verified by Ebenstein et al. [4], Lu et al. [7], Moradi et al. [65], Brunekreef and Holgate [66], Qi and Lu [67], and Mehmood et al. [43,68].

On the other hand, health costs would increase owing to environmental problems and pollution, particularly in the area of hospitalizations and medications used to treat or prevent diseases. Bai et al. [69] reviewed several studies on health costs accounting for China’s air pollution and revisited their association and interactions based on different accounting model specifications. Cui et al. [70] suggested that increases in air pollution would significantly increase the monetary cost of either curing or preventing associated diseases, while increases in health insurance coverage could have the opposite effect. Through estimating economic losses caused by pollution-related health damage, Cao and Han [71] emphasized that the health costs associated with haze pollution in Beijing were considerable, and that although in some cases such costs increased with a higher growth rate than GDP, these could be moderated by government efforts to control pollution. Moreover, economic losses resulting from pollution or the positive impacts of emissions on health costs have also been verified by Yazdi and Khanalizadeh [5], Chen and Chen [6], Miraglia et al. [72], Matus et al. [73], Jakubiak-Lasocka et al. [74], and Liao et al. [75]. More importantly, increasing medical and health costs could reinforce the inhibiting effect of environmental pollution on urbanization in China [56], while constructing district heating networks could bring significant advantages in terms of reducing health impacts, costs associated with urban development, and pollutant emissions in some cases [44].

In summary, numerous studies have focused on the urbanization–pollution relationship and revealed the associated bi-dimensional impacts and interactions [49]. However, most have concentrated on how urbanization affects environmental pollution, while few have focused on how pollution influences urban development. In addition, although the effects of different pollutants and their sources on urban population and land use differ [18], the heterogeneity of such impacts, however, has not been adequately considered in many studies. Additionally, the single proxy for urban scale and the ignorance of urban built-up land expansion may be against the Chinese land-centered urbanization context. Furthermore, the mechanisms and heterogeneity of the relationships or effects have not been fully explored.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su152215984

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!