Constructed wetlands (CWs) are artificially engineered treatment systems that utilize natural cycles or processes involving soils, wetland vegetation, and plant and soil-associated microbial assemblages to remediate contaminated water and improve its quality. CW treatment systems are typically categorized as free-water surface(FWSCWs), surface-flow constructed wetlands (SFCWs), subsurface-flow constructed wetlands (SSFCWs), and hybrid constructed wetlands (HCWs). Depending on the flow direction, Subsurface-flow CWs (SSFCWs) can be further classified into horizontal subsurface-flow (HSSF) and vertical subsurface-flow (VSSF) systems.

- circular bioeconomy (CBE)

- constructed wetlands (CWs)

- ecorestoration

- macrophytes

- wastewater treatment

1. Role of Macrophytes or Vegetation

-

Plants must adapt to local environmental conditions.

-

Plants must be practicable under local climatic conditions and may tolerate/resist potential pests, insects, and diseases.

-

Plants should tolerate various contaminants (e.g., N, OM, P, etc.) in the wastewater.

-

Plants should be easily adjusted in local CW environments to show relatively fast growth and spreading.

-

Plants should have a high pollutant elimination capacity.

2. Role of Substrate Materials

-

The media supports the growth of planted vegetation.

-

It stabilizes the bed (contact effect with the roots of developed plants).

-

It provides a media filtration effect.

-

It ensures high permeability and reduces possible clogging problems.

-

It provides an attractive attachment area for many microbes (biofilm formation) that are involved in pollutant removal processes.

-

It supports many transformation and elimination processes.

3. Role of (Plant Root-Associated) Microbes

4. Role of Influent-Feeding Mode

5. Role of Constructed Wetland (CW) as a Catalyst in Phytoremediation

5.1. Removal of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS)

5.2. Removal of Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD)

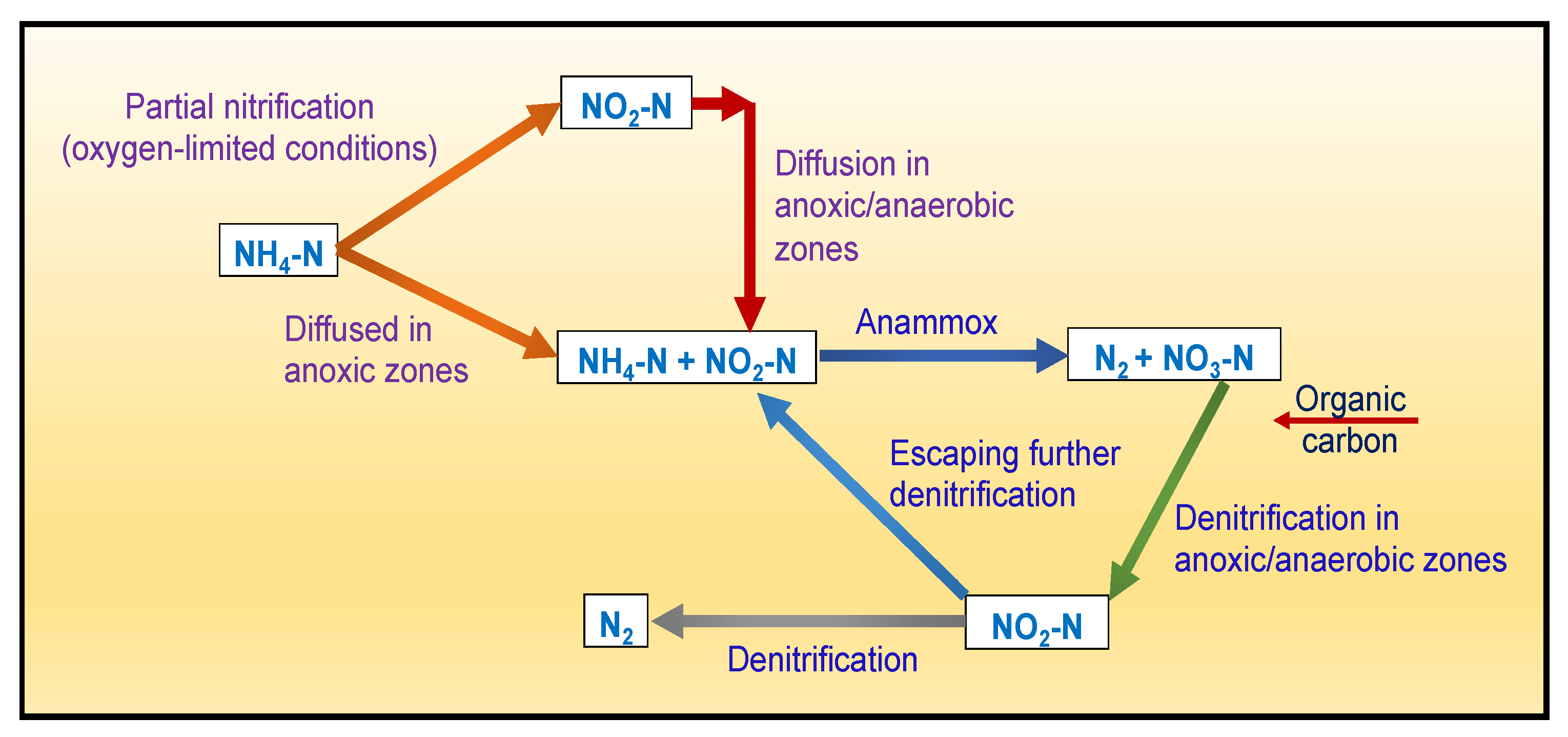

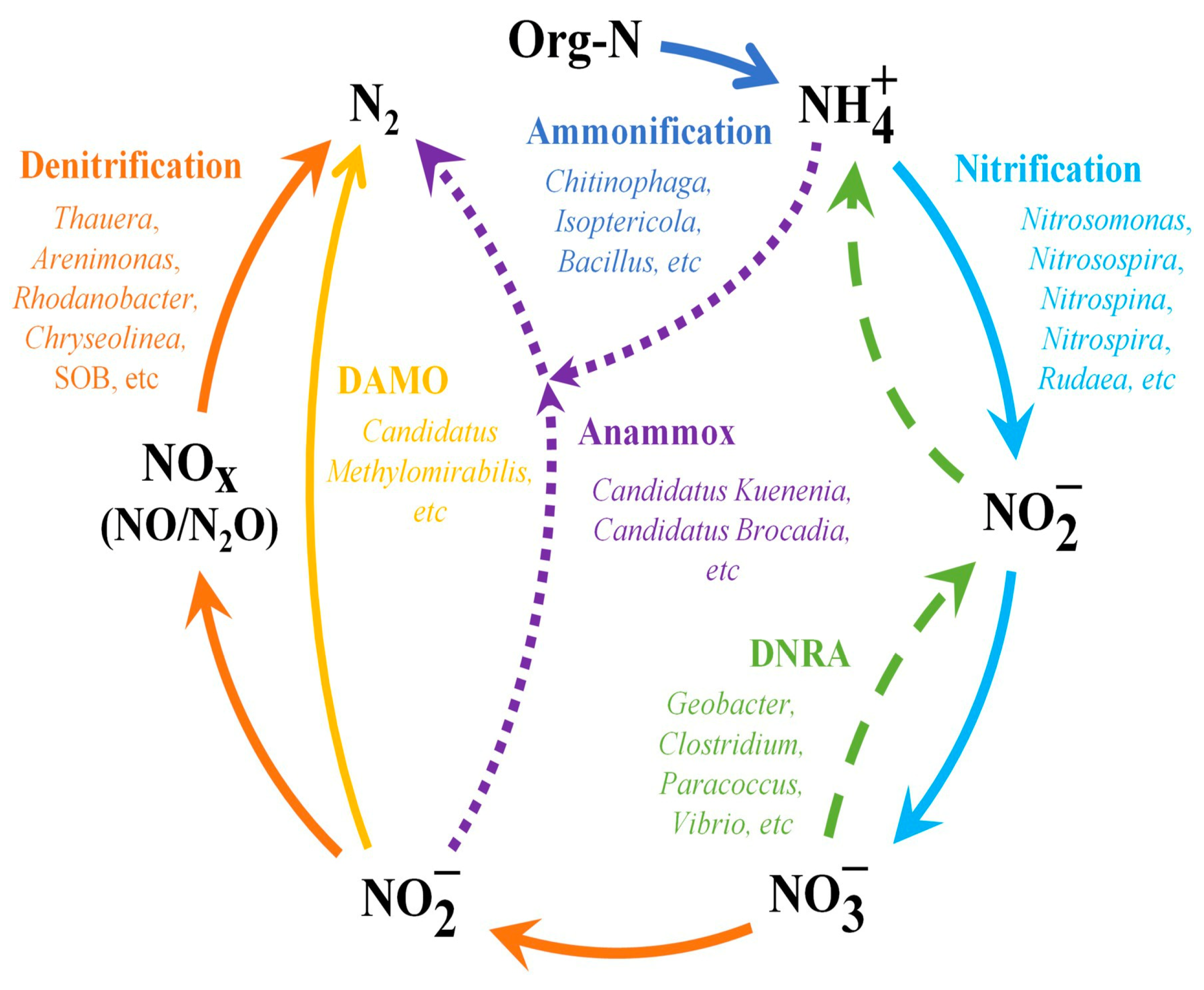

5.3. Removal of Total Nitrogen (TN)

5.4. Removal of Nitrates (NO3−)

Biological Removal Mechanism(s)

5.5. Removal of Phosphate (PO42−)

Physical Removal Mechanism(s)

Chemical Removal Mechanism(s)

Biological Removal Mechanism(s)

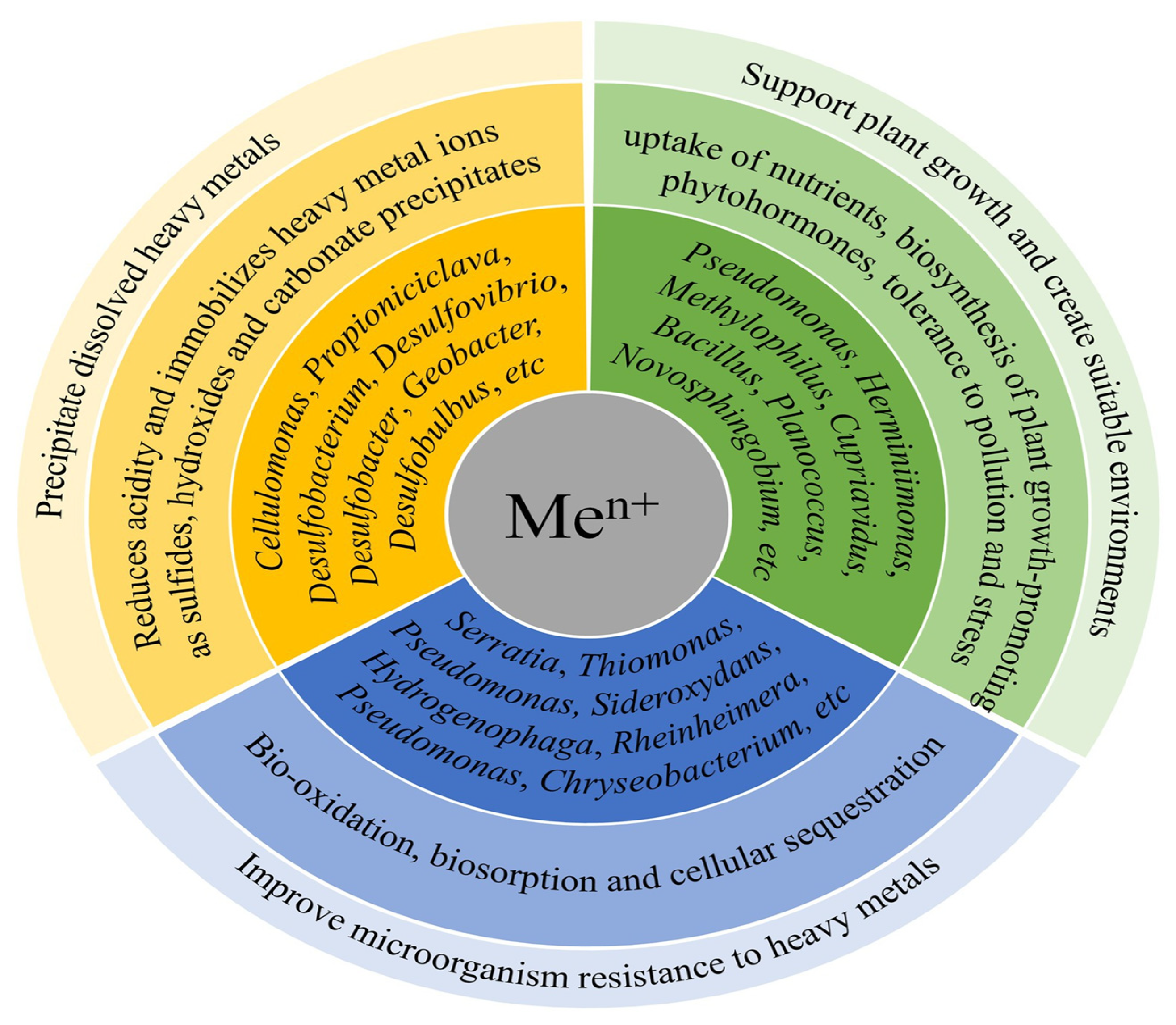

5.6. Removal of Heavy or Trace Metals

5.7. Removal of Pathogens

| Sl. No. | Latin and Common Names of Plant (Macrophyte) Species | Percentage Removal of Inorganic and Organic Pollutant(s) (%) | Percentage Removal of Pollutant Indicator Organism(s)/Pathogen(s) (%) | Microbes Involved in the Removal of Nutrient(s)/Pollutant(s) | Constructed-Wetland-Based Phytoremediation Set-Up(s)/System(s) Used | Type of Treated Wastewater | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Salix atrocinerea Brot. (grey willow) and Typha latifolia L. (cattail) | BOD5 (87.5) COD (89.0) SS (66.5) |

Fecal bacteria (99.9) | - | Full–scale, pilot-plant constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [71] |

| 2. | Control unit (A): Phragmites mauritianus Kunth (reed grass) and T. latifolia | COD (33.6, 56.3, and 60.7) NH4+-N (11.2, 25.2, and 23.0) NO2-N (23.9, 38.5, and 23.1) NO3−-N (32.2, 40.3, and 44.3) |

TC and FC (43.0–72.0) | - | Horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [72] |

| 3. | Control unit (A): Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott (taro) and T. latifolia | COD (64.7, 74.8, and 79.4) NH3 (74.0–75.0) P4 (72.0–77.0) SO42− (74.0–75.0) |

- | - | Engineered wetland | Domestic wastewater | [73] |

| T. latifolia | NH3 (74.0) PO42− (69.0) SO42− (72.0) |

- | - | ||||

| 4. | Phragmites sp. | BOD5 (93.0) COD (88.0) TDS (93.0) TSS (93.0) |

FC (76.0–99.0) Fecal Streptococci (49.0–85.0) Note: These were removed in two phases in four distinct seasons | - | Subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Municipal wastewater | [74] |

| Typha sp. | BOD5 (63.0) COD (50) TDS (58.0) TSS (58.0) |

FC (50.0–99.0) Fecal Streptococci (33.0–85.0) Note: These were removed in two phases in four distinct seasons |

- | ||||

| 5. | Pontederia crassipes Mart. [formerly Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms] (common water hyacinth) and Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. (common reed) | BOD5 (72.1) COD (67.2) Org-N (59.3) SS (64.6) Settleable solids (91.8) TN (38.0) TP (43.0) |

- | - | Surface-flow constructed wetland | Secondary-treated domestic wastewater | [75] |

| 6. | Typha angustifolia L. and Scirpus grossus L.f. (club-rush or bulrush) | BOD5 (68.2) NH4+-N (74.4) NO3−-N (50.0) TP (19.0) TSS (71.9) |

- | - | Free-water surface wetland | Secondary-treated municipal wastewater |

[76] |

| 7. | Lemna minor L. (common duckweed), P. australis, Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani (C.C. Gmel.) Palla (syn. Scirpus validus Vahl) (softstem bulrush), and Typha orientalis C. Presl (cumbungi) |

BOD5 (70.4) NH3-N (40.6) SS (71.8) TP (29.6) |

TC and FC (99.7 and 99.6, respectively) | - | Constructed wetland | Sewage water | [77] |

| 8. | A Acorus gramineus Sol. ex Aiton (Japanese sweet flag), B Iris pseudacorus L. (yellow flag) | BOD5 (A 71.3, B 72.5) COD (A 61.71, B 61.5) TN (11.24–21.95) TP (33.15) |

- | - | Constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [78] |

| 9. | A Iris pseudacorus L. and B Acorus gramineus Soland | BOD5 (72.5, 71.3) COD (61.1, 61.7) TN (70.9, 70.7) TP (86.9, 84.8) A HMs (Cd, Cr, and Pb)—15.3, 21.3, and 24.5, respectively) |

- | - | Model wetlands | Rural or urban domestic wastewater | [78] |

| 10. | T. angustifolia | BOD5 (80.78) NH4+-N (95.75) TN (66.5) TP (58.59) |

- | - | Free-water surface wetland | Secondary-treated municipal wastewater | [79] |

| 11. | Canna and Heliconia | TSS (88.0) COD (42–83) |

- | - | Horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetland |

Domestic wastewater | [80] |

| 12. | P. australis and T. latifolia | BOD5 (>86.0) COD (>86.0) |

- | - | Vertical-flow constructed wetland |

Domestic wastewater | [81] |

| 13. | Canna | BOD5 (94.0) TN (93.0) |

- | - | Vertical subsurface-flow constructed wetland and horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Sewage water | [82] |

| 14. | Cyperus alternifolius L. (umbrella papyrus) | COD (83.6) NH4+-N (71.4) TN (64.5) TP (68.1) TSS (99.0) |

- | - | Hybrid-flow constructed wetland | Municipal wastewater | [83] |

| 15. | Acorus calamus Linn. (sweet flag) | COD (73.0–93.0) TN (46.0–87.0) TOC (40.0–66.0) TP (75.0–90.0) |

- | - | Vertical-flow constructed wetland |

Domestic wastewater | [84] |

| 16. | Anthurium andraeanum Linden (flamingo flower), Strelitzia reginae Aiton (crane flower), Zantedeschia aethiopica (L.) Spreng. (calla lily), and Agapanthus africanus L. (African lily) |

BOD5 (81.94) TN (49.38) TP (50.14) TSS (61.56) |

TC (99.30) | - | Vertical subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Secondary-treated municipal wastewater | [85] |

| 17. | Canna, Cyperus papyrus L. (papyrus or Nile grass), and P. australis | BOD5 (90) COD (88.0) TSS (92) |

TC, FC, and E. coli (94.0–99.0) | - | Vertical-flow constructed wetland | Municipal wastewater | [86] |

| 18. | Canna indica L. (Indian shot) and T. orientalis | BOD5 (62.8) NH4+-N (80.72) NO3−-N (12.8) TN (51.1) |

- | - | Hybrid-flow constructed wetland | Municipal wastewater | [87] |

| 19. | Scirpus alternifolios (umbrella papyrus) | BOD5 (84.9) COD (89.8) NH4-N (82.2) TKN (82.7) TP (76.5) TSS (98.1) |

- | - | Vertical subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Wastewater | [88] |

| 20. | T. angustifolia | NH4+-N (95.2) TP (69.6) |

- | - | Subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Artificial wastewater | [16] |

| 21. | Canna and P. australis | BOD5 (92.8, 93.6) COD (91.5) NH3 (62.3, 57.1) TSS (92.3, 94.0) |

- | - | Vertical-flow and horizontal-flow constructed wetlands | Municipal wastewater | [89] |

| 22. | Alternanthera sessilis (L.) R.Br. ex DC. (Brazilian spinach), C. esculenta, P. australis, Pistia stratiotes L. (water lettuce), Persicaria hydropiper (L.) Delarbre (syn. Polygonum hydropiper L.) (water pepper), and T. latifolia |

BOD5 (90.0) NH4-N (86.0) NO3-N (84.0) TDS (78.0) TE (As, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb, and Zn—85.0, 49.0, 35.0, 95.0, 87.0, 39.0, 92.0, and 55.0, respectively) TSS (65.0) |

- | - | Subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Sewage wastewater | [90] |

| 23. | T. latifolia | COD (53.0–70.0) NH3 (12.0–15.0) P (18.0–25.0) |

- | - | Surface, up-flow constructed wetland | Sewage wastewater | [91] |

| 24. | Phragmites | CODCr (75.7) NH3-N (96.8) TN (96.7) TP (90.4) |

- | N was removed by Paenibacillus sp., Pseudomonas oleovorans, Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes, Pseudomonas stutzeri (LZ-4), Pseudomonas stutzeri (LZ-14), Pseudomonas stutzeri (XP-2), and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes (Note: These microbes remove N from wetlands with processes like adsorption, filtration, precipitation, sedimentation, and volatization); Pseudomonas mendocina LR contributed to the maximal N removal (97.35%) |

Laboratory-scale constructed wetland microcosm | River water and domestic wastewater | [92] |

| 25. | Canna and Phragmites | NH4+-N, NO3−-N and TKN (52.99) | - | - | Vertical-flow constructed wetland | Secondary-treated sewage wastewater | [93] |

| 26. | I. pseudacorus, P. australis, and T. latifolia |

BOD5 (41.0) Dissolved P (59.0) HM (Pb—98.0) NH4+-N (66.0) TP (46.0) SS (66) |

- | - | Constructed wetland | Mine water and Sewage | [94] |

| 27. | Agapanthus africanus (L.) Hoffman. (African lily), Canna ffuses, C. indica, Watsonia borbonica (Pourr.) Goldblatt (Cape bugle lily), and Z. aethiopica |

BOD5 (90.0) NH4+ (84.0) PO42− (92.0) |

- | - | Horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Sewage water | [95] |

| 28. | Aquatic plants | BOD5 (87.9) CODCr (90.6) NH3-N (66.7) TN (63.4) TP (92.6) |

- | - | New-type, multi-layer artificial wetland | Domestic wastewater | [96] |

| 29. | Canna × generalis | NO3− (51.9) P (8.9) Phenolic compounds (1.0) |

- | - | Constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [28] |

| 30. | A. calamus, C. indica, Iris japonica Thunb. (butterfly flower), P. australis, T. angustifolia, and Zizania caduciflora (Trin.) Hand.-Mazz. (wild rice) |

TP (79.6, 87.9, 90.3, and 93.2) |

- | - | Integrated vertical-flow constructed wetland | Synthetic domestic wastewater | [97] |

| 31. | P. australis | BOD5 (84.0) COD (75.0) NH4+ (32.0) TP (22.0) TSS (75.0) |

- | - | Vertical subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Sewage water | [98] |

| 32. | C. indica | BOD5 (88.11, 80.51, and 89.78) NH4+-N (94.81, 39.39) TN (56.17, 50.0, and 55.06) TP (94.82, 93.04, and 93.31) |

- | N was removed by denitrifying bacteria | Hybrid vertical down-flow constructed wetland |

Domestic wastewater | [99] |

| 33. | A. calamus and P. australis | TN (45.2) | - | N was removed by a large number of rhizospheric bacteria (out of that, 17.9–26.8% non-rhizospheric bacteria removed N from the soil) | Horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [100] |

| 34. | Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. (Indian pennywort), E. crassipes, P. australis, T. latifolia, and Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty (vetiver grass) |

BOD5 (81.0 and 82.0) TKN (63.0 and 69.0) TSS (79.0 and 89.0) |

- | - | Hybrid constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [101] |

| 35. | Typha domingensis Pers. (southern cattail) | BOD5 (56.0) TKN (41.0) TP (37.0) TSS (78.0) |

- | - | Constructed floating wetland | Domestic sewage | [102] |

| 36. | P. australis | BOD5 (93.0) COD (91.0) TN (67.0) TP (62.0) TSS (95.0) |

TC, FC, and fecal Streptococci (64.0, 63.0, and 61.0, respectively) | - | Hybrid constructed wetland | Wastewater | [103] |

| 37. | Typha and Commelina benghalensis L. (Benghal dayflower) | NO3− (84.0) PO43− (77.0) |

TC and FC, E. coli, Enterococcus, Clostridium, and Salmonella (65.0–70.0) | - | Horizontal-flow constructed wetland | Primary and secondary-treated sewage | [104] |

| 38. | Pennisetum purpureum Schumach. (Napier grass) and T. latifolia | BOD5 (up to 87) (inlet BOD5 of 748–1642 mg L−1) COD (up to 81) (inlet COD of 835–2602 mg L−1) |

- | - | Horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetlands |

Industrial (brewery) wastewater | [105] |

| 39. | C. indica and Typha angustata Bory & Chaub. (accepted name: Typha domingensis Pers.) | BOD, COD, NH3-N, TDS, TKN, TP, and TVS (A 65.0–B 62.0, A 64.0–B 61.0, A 21.0–B 58.0, A 34.0–B 33.0, A 15.0–B 35.0, and A 54.0– B 40.0) [at first stage] and (A 88.0–B 84.0, A 90.0–B 90.0, A 52.0–B 82.0, A 58.0–B 61.0, A 50.0–B 47.0, and A 71.0–B 64.0) [for the second stage reactor] Note: The nutrient removal was measured at two different hydraulic loadings at A 0.150 m day−1 and at B 0.225 m day−1 |

- | - | Two-stage vertical-flow constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [106] |

| 40. | C. papyrus and P. australis | BOD5 (80.69) COD (69.87) NH3-N (69.69) TP (50.0) |

TC and FC (98.08 and 95.61, respectively) | - | Vertical-flow subsurface constructed wetlands |

Municipal wastewater | [107] |

| 41. | A. calamus and C. indica | BOD5 (78.74 and 81.79) TDS (18.96 and 22.31) TN (56.33 and 60.37) PO42− (79.57 and 81.53) |

- | - | Pilot-scale vertical subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Primary-treated domestic sewage | [108] |

| 42. | Myriophyllum elatinoides Gaudich. (water milfoil) | NH4+ (91.35) NO3− (95.16) TN (90.36) TP (96.14) |

- | Bacteroides and Firmicutes carried out denitrification; N was removed by Pseudomonas, Dechloromonas, Desulfobacca, and Desulfomicrobium; PO42− was removed by Chlorobaculum, Methanobacterium, and Rhodoblastus |

Multi-stage, surface-flow constructed wetland | Domestic sewage | [40] |

| 43. | C. esculenta and Dracaena sanderiana Sander ex Mast. (Chinese water bamboo) |

BOD5/ (74.0) NH4-N (90.0) TSS (76.0) |

TC (59.0) | - | Novel vertical-flow and free-water surface constructed wetland | Dormitory sewage | [109] |

| 44. | A. calamus and reeds | TN (15.0) TP (18.0) |

- | Bioremediation and degradation of diesel, petroleum, and other alkanes could be achieved by Tistrella; N was removed by Achromobacter, Aeromicrobium, Aquicella, Azospirillum, Fluviicola, Halomonas, Limnohabitans, Methylophilacterium, Perlucidibaca, Pseudomonas, Rhodobacter, Rhodospirillaceae, and Variovorax; S compounds were removed by Desulfovibrio and Rhodocista |

Constructed wetland | Domestic sewage | [59] |

| 45. | C. indica, C. alternifolius, and Thalia dealbata Fraser ex Roscoe (powdery alligator-flag) |

COD (95.2) NH4-N (98.1) PO4−-P (85.3) TN (87.9) TP (86.1) |

- | - | Hybrid constructed wetland | Domestic sewage | [110] |

| 46. | Chrysopogon zizanioides L. (vetiver and khus) | BOD5 (83.36) COD (92.34) NH4-N (89.41) NO3-N (90.72) PO4−-P (92.81) TCr (95.20) TN (93.54) TSS (94.66) |

- | - | Horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Tannery wastewater | [111] |

| 47. | A Commelina benghalensis L. (Benghal dayflower) and B T. latifolia | A,B BOD (61.0 and 59.0) A,B COD (58.0 and 53.0) A,B NH4+ (60.3 and 51.5) A,B NO3-N (60.3 and 51.5) A,B PO42−(61.0 and 64.0) |

A,B TC (41.0 and 39.0) A,B FC (50.0 and 30.0) A,B E. coli (45.0 and 35.0) |

- | Horizontal-flow constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [111] |

| 48. | Oenanthe javanica DC. (water celery) | COD (38.65) NH4+-N (28.20) TN (18.82) TP (14.57) |

- | Purification of micro-polluted water was improved indirectly by inoculating low temperature-resistant Bacillus spp., via altering the community structure of the wetland microbes (i.e., through stimulating beneficial microbes for treating sewage while inhibiting microbial pathogens) | Vertical subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Micro-polluted lake water | [112] |

| 49. | A Canna indica L. (Indian shot) and B Iris sibrica L. (Siberian flag) | A,B COD (83.6 and 66.3) A,B NH4+-N (82.7 and 44.1) A,B TN (76.8 and 43.8) |

- | - | Horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetland | Domestic wastewater | [62] |

| 50. | P. australis | TP (36.2– 87.5) | - | - | Microbial-enhanced constructed wetlands | P-rich Saline wastewater | [113] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/w15223877

References

- Tanner, C.C. Plants for constructed wetland treatment systems–A comparison of the growth and nutrient uptake of eight emergent species. Ecol. Eng. 1996, 7, 59–83.

- Gingerich, R.T.; Panaccione, D.G.; Anderson, J.T. The role of fungi and invertebrates in litter decomposition in mitigated and reference wetlands. Limnologica 2015, 54, 23–32.

- Sirianuntapiboon, S.; Kongchum, M.; Jitmaikasem, W. Effects of hydraulic retention time and media of constructed wetland for treatment of domestic wastewater. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2006, 1, 027–037.

- Wang, Y.; Shen, L.; Wu, J.; Zhong, F.; Cheng, S. Step-feeding ratios affect nitrogen removal and related microbial communities in multi-stage vertical flow constructed wetlands. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 721, 137689.

- Si, Z.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Cao, X.; Zhang, X.; Sand, W. Mechanism and performance of trace metal removal by continuous-flow constructed wetlands coupled with a micro-electric field. Water Res. 2019, 164, 114937.

- Bijalwan, A.; Thakur, T. Effect of IBA and age of cuttings on rooting behaviour of Jatropha curcas L. in different seasons in Western Himalaya, India. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2010, 4, 387–390.

- Bessa, V.; Moreira, I.; Tiritan, M.; Castro, P. Enrichment of bacterial strains for the biodegradation of diclofenac and carbamazepine from activated sludge. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 120, 135–142.

- Kumar, S.; Bijalwan, A.; Singh, B.; Rawat, D.; Yewale, A.G.; Riyal, M.K.; Thakur, T.K. Comparison of Carbon Sequestration Potential of Quercus leucotrichophora Based Ag-roforestry Systems and Natural Forest in Central Himalaya, India. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 350.

- Vassallo, A.; Miceli, E.; Fagorzi, C.; Castronovo, L.M.; Del Duca, S.; Chioccioli, S.; Venditto, S.; Coppini, E.; Fibbi, D.; Fani, R. Temporal Evolution of Bacterial Endophytes Associated to the Roots of Phragmites australis Exploited in Phytodepuration of Wastewater. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1652.

- Wang, J.; Long, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, S. A Review on Microorganisms in Constructed Wetlands for Typical Pollutant Removal: Species, Function, and Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 845725.

- Mukherjee, P.; Mitra, A.; Roy, M. Halomonas Rhizobacteria of Avicennia marina of Indian Sundarbans Promote Rice Growth Under Saline and Heavy Metal Stresses Through Exopolysaccharide Production. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1207.

- Agarwal, S.; Mukherjee, P.; Pramanick, P.; Mitra, A. Seasonal Variations in Bioaccumulation and Translocation of Toxic Heavy Metals in the Dominant Vegetables of East Kolkata Wetlands: A Case Study with Suggestive Ecorestorative Strategies. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 2332–2358.

- Roy, M.; Pandey, V.C. Role of microbes in grass-based phytoremediation. In Phytoremediation Potential of Perennial Grasses; Pandey, V.C., Singh, D.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 303–327.

- Mishra, P.; Mishra, J.; Dwivedi, S.K.; Arora, N.K. Microbial Enzymes in Biocontrol of Phytopathogens. In Microbial Enzymes: Roles and Applications in Industries. Microorganisms for Sustainability; Arora, N., Mishra, J., Mishra, V., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 259–285.

- Zhang, D.Q.; Tan, S.K.; Gersberg, R.M.; Zhu, J.; Sadreddini, S.; Li, Y. Nutrient removal in tropical subsurface flow constructed wetlands under batch and continuous flow conditions. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 96, 1–6.

- Caselles-Osorio, A.; Garcia, J. Effect of physico-chemical pretreatment on the removal efficiency of horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetlands. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 146, 55–63, ISSN 0269-7491.

- Brix, H.; Schierup, H. Danish experience with sewage treatment in constructed wetlands. In Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment; Hammer, D.A., Ed.; Lewis Publishers: Chelsea, MI, USA, 1989; pp. 565–573.

- Shelef, O.; Gross, A.; Rachmilevitch, S. Role of Plants in a Constructed Wetland: Current and New Perspectives. Water 2013, 5, 405–419.

- Sawyer, C.N.; McCarty, P.L.; Parkin, G.F. Chemistry for Environmental Engineering and Science, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003.

- Kadlec, R.H.; Knight, R.L. Treatment Wetlands; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 1996.

- Akinbile, C.O.; Yusoff, M.S. Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) and Lettuce (Pistia stratiotes) effectiveness in aquaculture wastewater treatment in Malaysia. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2012, 14, 201–211.

- US, EPA. Manual: Constructed Wetlands Treatment of Municipal Wastewaters; EPA/625/R-99/010; U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2000.

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.-J.; Huang, J.-C.; Sun, S.; Cui, X.; Zhou, W.; He, S. Salinity-driven nitrogen removal and its quantitative molecular mechanisms in artificial tidal wetlands. Water Res. 2021, 202, 117446.

- Ye, F.; Li, Y. Enhancement of nitrogen removal in towery hybrid constructed wetland to treat domestic wastewater for small rural communities. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 35, 1043–1050.

- Vymazal, J. Removal of nutrients in various types of constructed wetlands. Sci. Total. Environ. 2007, 380, 48–65.

- Tan, X.; Yang, Y.-L.; Liu, Y.-W.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.-B. Quantitative ecology associations between heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification, nitrogen-metabolism genes, and key bacteria in a tidal flow constructed wetland. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 337, 125449.

- Saeed, T.; Sun, G. A review on nitrogen and organics removal mechanisms in subsurface flow constructed wetlands: Dependency on environmental parameters, operating conditions and supporting media. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 112, 429–448.

- Ojoawo, S.O.; Udayakumar, G.; Naik, P. Phytoremediation of Phosphorus and Nitrogen with Canna × generalis Reeds in Domestic Wastewater through NMAMIT Constructed Wetland. Aquat. Procedia 2015, 4, 349–356.

- Hu, Y.; He, F.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z. Microbial nitrogen removal pathways in integrated vertical-flow constructed wetland systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 207, 339–345.

- Xie, E.; Ding, A.; Zheng, L.; Lu, C.; Wang, J.; Huang, B.; Xiu, H. Seasonal variation in populations of nitrogen-transforming bacteria and correlation with nitrogen removal in a full-scale horizontal flow constructed wetland treating Polluted River water. Geomicrobiol. J. 2016, 33, 338–346.

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, X.; Song, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Si, Z.; Lin, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y. Montmorillonite supported nanoscale zero-valent iron immobilized in sodium alginate (SA/Mt-NZVI) enhanced the nitrogen removal in vertical flow constructed wetlands (VFCWs). Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 267, 608–617.

- Lee, S.; Maniquiz-Redillas, M.C.; Choi, J.; Kim, L.-H. Nitrogen mass balance in a constructed wetland treating piggery wastewater effluent. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 1260–1266.

- Tan, X.; Yang, Y.-L.; Liu, Y.-W.; Yin, W.-C.; Fan, X.-Y. The synergy of porous substrates and functional genera for efficient nutrients removal at low temperature in a pilot-scale two-stage tidal flow constructed wetland. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124135.

- Zhang, M.; Huang, J.-C.; Sun, S.; Rehman, M.M.U.; He, S.; Zhou, W. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction processes and corresponding nitrogen loss in tidal flow constructed wetlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126429.

- Wang, W.; Su, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Zhu, G. Spatiotemporal shifts of ammonia-oxidizing archaea abundance and structure during the restoration of a multiple pond and plant-bed/ditch wetland. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 684, 629–640.

- Zhao, L.; Fu, G.; Wu, J.; Pang, W.; Hu, Z. Bioaugmented constructed wetlands for efficient saline wastewater treatment with multiple denitrification pathways. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 335, 125236.

- Wang, T.; Xiao, L.; Lu, H.; Lu, S.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Zhao, X. Nitrogen removal from summer to winter in a field pilot-scale multistage constructed wetland-pond system. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 111, 249–262.

- Liu, T.; Lu, S.; Wang, R.; Xu, S.; Qin, P.; Gao, Y. Behavior of selected organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) and their influence on rhizospheric microorganisms after short-term exposure in integrated vertical-flow constructed wetlands (IVCWs). Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 710, 136403.

- Huang, T.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, Z.; He, F. A stable simultaneous anammox, denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation and denitrification process in integrated vertical constructed wetlands for slightly polluted wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114363.

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Lv, D.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance and bacterial communities in a multi-stage surface flow constructed wetland treating rural domestic sewage. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 709, 136235.

- Zhang, M.; Huang, J.-C.; Sun, S.; Rehman, M.M.U.; He, S. Depth-specific distribution and significance of nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation process in tidal flow constructed wetlands used for treating river water. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 716, 137054.

- Kraiem, K.; Kallali, H.; Wahab, M.A.; Fra-Vazquez, A.; Mosquera-Corral, A.; Jedidi, N. Comparative study on pilots between ANAMMOX favored conditions in a partially saturated vertical flow constructed wetland and a hybrid system for rural wastewater treatment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 670, 644–653.

- Li, Q.; Bu, C.; Ahmad, H.A.; Guimbaud, C.; Gao, B.; Qiao, Z.; Ding, S.; Ni, S.-Q. The distribution of dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium bacteria in multistage constructed wetland of Jining, Shandong, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 4749–4761.

- Rahman, M.M.; Roberts, K.L.; Grace, M.R.; Kessler, A.J.; Cook, P.L.M. Role of organic carbon, nitrate and ferrous iron on the partitioning between denitrification and DNRA in constructed stormwater urban wetlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 608–617.

- Zhang, M.; Huang, J.-C.; Sun, S.; Rehman, M.M.U.; He, S.; Zhou, W. Nitrogen removal through collaborative microbial pathways in tidal flow constructed wetlands. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 758, 143594.

- Si, Z.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Arefe, A. Intensified heterotrophic denitrification in constructed wetlands using four solid carbon sources: Denitrification efficiency and bacterial community structure. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 267, 416–425.

- Ajibade, F.O.; Wang, H.-C.; Guadie, A.; Ajibade, T.F.; Fang, Y.-K.; Sharif, H.M.A.; Liu, W.-Z.; Wang, A.-J. Total nitrogen removal in biochar amended non-aerated vertical flow constructed wetlands for secondary wastewater effluent with low C/N ratio: Microbial community structure and dissolved organic carbon release conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 322, 124430.

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Song, X.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Si, Z.; Pan, F. Effects of nZVI dosing on the improvement in the contaminant removal performance of constructed wetlands under the dye stress. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 703, 134789.

- Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council. Phytotechnology Technical and Regulatory Guidance and Decision Trees, Revised; ITRC: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. Available online: www.itrcweb.org (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Du, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, D.; Wu, Z. Phosphorus removal performance and biological dephosphorization process in treating reclaimed water by Integrated Vertical-flow Constructed Wetlands (IVCWs). Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 204–211.

- Wang, Q.; Ding, J.; Xie, H.; Hao, D.; Du, Y.; Zhao, C.; Xu, F.; Kong, Q.; Wang, B. Phosphorus removal performance of microbial-enhanced constructed wetlands that treat saline wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125119.

- Mitsch, J.W.; Gosselink, J.G. Wetlands; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, NY, USA, 1986.

- Babatunde, A.; Zhao, Y.; Burke, A.; Morris, M.; Hanrahan, J. Characterization of aluminium-based water treatment residual for potential phosphorus removal in engineered wetlands. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 2830–2836.

- Shi, X.; Fan, J.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y. Enhanced phosphorus removal in intermittently aerated constructed wetlands filled with various construction wastes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 22524–22534.

- Tian, J.; Yu, C.; Liu, J.; Ye, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L. Performance of an ultraviolet Mutagenetic polyphosphate-accumulating bacterium PZ2 and its application for wastewater treatment in a newly designed constructed wetland. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 181, 735–747.

- Lv, R.; Wu, D.; Ding, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, Q.; Zhao, C.; Du, Y.; Xu, F.; et al. Long-term performance and microbial mechanism in intertidal wetland sediment introduced constructed wetlands treating saline wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127409.

- Huang, J.; Xiao, J.; Guo, Y.; Guan, W.; Cao, C.; Yan, C.; Wang, M. Long-term effects of silver nanoparticles on performance of phosphorus removal in a laboratory-scale vertical flow constructed wetland. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 87, 319–330.

- Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, R.; Wu, J. Bacterial community dynamics in a Myriophyllum elatinoides purification system for swine wastewater in sediments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 119, 56–63.

- Wu, H.; Gao, X.; Wu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Xiong, R.; Ye, S. The efficiency and risk to groundwater of constructed wetland system for domestic sewage treatment-A case study in Xiantao, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123384.

- Yu, G.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Chi, T.; Wang, S.; Peng, H.; Chen, H.; Du, C.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Y.; et al. Enhanced Cd2+ and Zn2+ removal from heavy metal wastewater in constructed wetlands with resistant microorganisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 316, 123898.

- Thakur, T.K.; Dutta, J.; Upadhyay, P.; Patel, D.K.; Thakur, A.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, A. Assessment of land degradation and restoration in coal mines of central India: A time series analysis. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 175, 106493.

- Chen, X.; Zhong, F.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Cheng, S. The Interaction Effects of Aeration and Plant on the Purification Performance of Horizontal Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1583.

- Teitzel, G.M.; Parsek, M.R. Heavy metal resistance of biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 2313–2320.

- Cristani, M.; Naccari, C.; Nostro, A.; Pizzimenti, A.; Trombetta, D.; Pizzimenti, F. Possible use of Serratia marcescens in toxic metal biosorption (removal). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 161–168.

- Zhou, Y.; Tigane, T.; Li, X.; Truu, M.; Truu, J.; Mander, Ü. Hexachlorobenzene dechlorination in constructed wetland mesocosms. Water Res. 2013, 47, 102–110.

- Sturz, A.V.; Christie, B.R.; Nowak, J. Bacterial Endophytes: Potential Role in Developing Sustainable Systems of Crop Production. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2000, 19, 1–30.

- Syranidou, E.; Christofilopoulos, S.; Gkavrou, G.; Thijs, S.; Weyens, N.; Vangronsveld, J.; Kalogerakis, N. Exploitation of Endophytic Bacteria to Enhance the Phytoremediation Potential of the Wetland Helophyte Juncus acutus. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 07, 1016.

- Agarwal, S.; Darbar, S.; Saha, S. Challenges in management of domestic wastewater for sustainable development. In Current Directions in Water Scarcity Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 531–552.

- Maiga, Y.; von Sperling, M.; Mihelcic, J.R. Constructed Wetlands. In Water and Sanitation for the 21st Century: Health and Microbiological Aspects of Excreta and Wastewater Management (Global Water Pathogen Project). (Mihelcic JR, Verbyla ME (eds), Part 4: Management of Risk from Excreta and Wastewater-Section: Sanitation System Technologies, Pathogen Reduction in Sewered System Technologies); Rose, J.B., Jiménez-Cisneros, B., Eds.; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2017.

- Dotro, G.; Langergraber, G.; Molle, P.; Nivala, J.; Puigagut Juárez, J.; Stein, O.R.; von Sperling, M. Treatment Wetlands; Biological Wastewater Treatment Series (Volume 7); IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2017.

- Ansola, G.; González, J.M.; Cortijo, R.; de Luis, E. Experimental and full–scale pilot plant constructed wetlands for municipal wastewaters treatment. Ecol. Eng. 2003, 21, 43–52.

- Kaseva, M. Performance of a sub-surface flow constructed wetland in polishing pre-treated wastewater—A tropical case study. Water Res. 2004, 38, 681–687.

- Mbuligwe, S.E. Comparative effectiveness of engineered wetland systems in the treatment of anaerobically pre-treated domestic wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2004, 23, 269–284.

- Solano, M.; Soriano, P.; Ciria, M. Constructed Wetlands as a Sustainable Solution for Wastewater Treatment in Small Villages. Biosyst. Eng. 2004, 87, 109–118.

- Slak, A.S.; Bulc, T.G.; Vrhovsek, D. Comparison of nutrient cycling in a surface-flow constructed wetland and in a facultative pond treating secondary effluent. Water Sci. Technol. 2005, 51, 291–298.

- Jinadasa, K.B.S.N.; Tanaka, N.; Mowjood, M.I.M.; Werellagama, D.R.I.B. Free water surface constructed wetlands for domestic wastewater treatment: A tropical case study. Chem. Ecol. 2006, 22, 181–191.

- Song, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, X.; Han, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, M. Seasonal and annual performance of a full-scale constructed wetland system for sewage treatment in China. Ecol. Eng. 2006, 26, 272–282.

- Zhang, X.-B.; Liu, P.; Yang, Y.-S.; Chen, W.-R. Phytoremediation of urban wastewater by model wetlands with ornamental hydrophytes. J. Environ. Sci. 2007, 19, 902–909.

- Katsenovich, Y.P.; Hummel-Batista, A.; Ravinet, A.J.; Miller, J.F. Performance evaluation of constructed wetlands in a tropical region. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 35, 1529–1537.

- Konnerup, D.; Koottatep, T.; Brix, H. Treatment of domestic wastewater in tropical, subsurface flow constructed wetlands planted with Canna and Heliconia. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 35, 248–257.

- Morari, F.; Giardini, L. Municipal wastewater treatment with vertical flow constructed wetlands for irrigation reuse. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 35, 643–653.

- Xinshan, S.; Qin, L.; Denghua, Y. Nutrient Removal by Hybrid Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetlands for High Concentration Am-monia Nitrogen Wastewater. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2010, 2, 1461–1468.

- Zhai, J.; Xiao, H.W.; Kujawa-Roeleveld, K.; He, Q.; Kerstens, S.M. Experimental study of a novel hybrid constructed wetland for water reuse and its application in Southern China. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 64, 2177–2184.

- Zhao, Y.J.; Hui, Z.; Chao, X.; Nie, E.; Li, H.J.; He, J.; Zheng, Z. Efficiency of two-stage combinations of subsurface vertical down-flow and up-flow constructed wetland systems for treating variation in influent C/N ratios of domestic wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 1546–1554.

- Zurita, F.; Belmont, M.A.; De Anda, J.; White, J.R. Seeking a way to promote the use of constructed wetlands for domestic wastewater treatment in developing countries. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 63, 654–659.

- Abou-Elela, S.I.; Hellal, M.S. Municipal wastewater treatment using vertical flow constructed wetlands planted with Canna, Phragmites and Cyprus. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 47, 209–213.

- Chang, J.-J.; Wu, S.-Q.; Dai, Y.-R.; Liang, W.; Wu, Z.-B. Treatment performance of integrated vertical-flow constructed wetland plots for domestic wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 44, 152–159.

- Villara, M.M.P.; Domínguez, E.R.; Tack, F.; Ruiz, J.M.H.; Morales, R.S.; Arteaga, L.E. Vertical subsurface wetlands for wastewater purification. Procedia Eng. 2012, 42, 1960–1968.

- Abou-Elela, S.I.; Golinielli, G.; Abou-Taleb, E.M.; Hellal, M.S. Municipal wastewater treatment in horizontal and vertical flows constructed wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 61, 460–468.

- Rai, U.; Tripathi, R.; Singh, N.; Upadhyay, A.; Dwivedi, S.; Shukla, M.; Mallick, S.; Singh, S.; Nautiyal, C. Constructed wetland as an ecotechnological tool for pollution treatment for conservation of Ganga river. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 148, 535–541.

- Badhe, N.; Saha, S.; Biswas, R.; Nandy, T. Role of algal biofilm in improving the performance of free surface, up-flow constructed wetland. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 169, 596–604.

- Shao, Y.; Pei, H.; Hu, W.; Chanway, C.P.; Meng, P.; Ji, Y.; Li, Z. Bioaugmentation in lab scale constructed wetland microcosms for treating polluted river water and domestic wastewater in northern China. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 95, 151–159.

- Sharma, G.; Priya; Brighu, U. Performance Analysis of Vertical up-flow Constructed Wetlands for Secondary Treated Effluent. APCBEE Procedia 2014, 10, 110–114.

- Younger, P.L.; Henderson, R. Synergistic wetland treatment of sewage and mine water: Pollutant removal performance of the first full-scale system. Water Res. 2014, 55, 74–82.

- Calheiros, C.S.C.; Bessa, V.S.; Mesquita, R.B.R.; Brix, H.; Rangel, A.O.S.S.; Castro, P.M.L. Constructed wetland with a polyculture of ornamental plants for wastewater treatment at a rural tourism facility. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 79, 1–7, ISSN 0925-8574.

- Lu, S.; Pei, L.; Bai, X. Study on method of domestic wastewater treatment through new-type multi-layer artificial wetland. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 11207–11214.

- Xu, D.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Howard, A.; Guan, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, H. The forms and bioavailability of phosphorus in integrated vertical flow constructed wetland with earthworms and different substrates. Chemosphere 2015, 134, 492–498.

- Abdelhakeem, S.G.; Aboulroos, S.A.; Kamel, M.M. Performance of a vertical subsurface flow constructed wetland under different operational conditions. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 803–814.

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cui, L.; Yu, G. Optimization of operating parameters of hybrid vertical down-flow constructed wetland systems for domestic sewerage treatment. Environ. Manag. 2016, 180, 384–389.

- Hua, Y.; Peng, L.; Zhang, S.; Heal, K.V.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, D. Effects of plants and temperature on nitrogen removal and microbiology in pilot-scale horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands treating domestic wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 108, 70–77.

- Ali, M.; Rousseau, D.P.; Ahmed, S. A full-scale comparison of two hybrid constructed wetlands treating domestic wastewater in Pakistan. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 210, 349–358.

- Benvenuti, T.; Hamerski, F.; Giacobbo, A.; Bernardes, A.M.; Zoppas-Ferreira, J.; Rodrigues, M.A. Constructed floating wetland for the treatment of domestic sewage: A real-scale study. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5706–5711.

- Elfanssi, S.; Ouazzani, N.; Latrach, L.; Hejjaj, A.; Mandi, L. Phytoremediation of domestic wastewater using a hybrid constructed wetland in mountainous rural area. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2018, 20, 75–87.

- Mishra, V.K.; Otter, P.; Shukla, R.; Goldmaier, A.; Alvarez, J.A.; Khalil, N.; Avila, C.; Arias, C.; Ameršek, I. Application of horizontal flow constructed wetland and solar driven disinfection technologies for wastewater treatment in India. Water Pract. Technol. 2018, 13, 469–480.

- Worku, A.; Tefera, N.; Kloos, H.; Benor, S. Constructed wetlands for phytoremediation of industrial wastewater in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2018, 3, 9.

- Yadav, A.; Chazarenc, F.; Mutnuri, S. Development of the “French system” vertical flow constructed wetland to treat raw domestic wastewater in India. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 113, 88–93.

- García-Ávila, F.; Avilés-Añazco, A.; Sánchez-Cordero, E.; Valdiviezo-Gonzáles, L.; Ordoñez, M.D.T. The challenge of improving the efficiency of drinking water treatment systems in rural areas facing changes in the raw water quality. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 37, 141–149.

- Barya, M.P.; Gupta, D.; Thakur, T.K.; Shukla, R.; Singh, G.; Mishra, V.K. Phytoremediation performance of Acorus calamus and Canna indica for the treatment of primary treated domestic sewage through vertical subsurface flow constructed wetlands: A field-scale study. Water Pract. Technol. 2020, 15, 528–539.

- Nguyen, X.C.; Nguyen, D.D.; Tran, Q.B.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Tran, T.K.A.; Tran, T.C.P.; Nguyen, T.H.G.; Tran, T.N.T.; La, D.D.; Chang, S.W.; et al. Two-step system consisting of novel vertical flow and free water surface constructed wetland for effective sewage treatment and reuse. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 306, 123095.

- Xiong, C.; Tam, N.F.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y. Enhanced performance of pilot-scale hybrid constructed wetlands with A/O reactor in raw domestic sewage treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 258, 110026.

- Aregu, M.B.; Asfaw, S.L.; Khan, M.M. Developing horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland using pumice and Chrysopogon zizanioides for tannery wastewater treatment. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021, 10, 33.

- Shukla, R.; Gupta, D.; Singh, G.; Mishra, V.K. Performance of horizontal flow constructed wetland for secondary treatment of domestic wastewater in a remote tribal area of Central India. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2021, 31, 13.

- Gao, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Song, B.; Huang, Z. Purification of Micro-Polluted Lake Water by Biofortification of Vertical Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetlands in Low-Temperature Season. Water 2022, 14, 896.