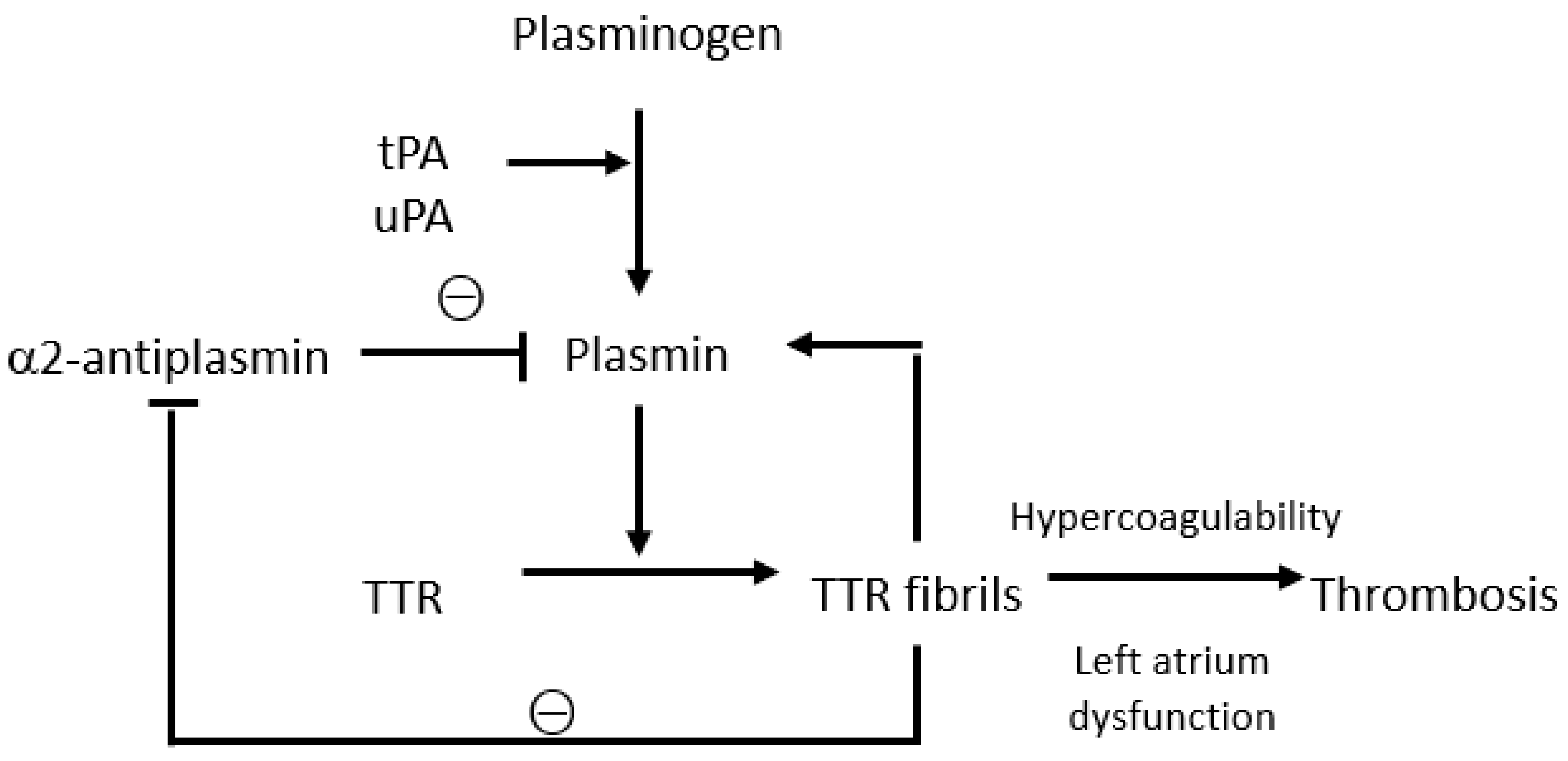

Transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) is a group of diseases caused by the deposition of insoluble fibrils derived from misfolded transthyretin, which compromises the structure and function of various organs, including the heart. Thromboembolic events and increased bleeding risk are among the most important complications of ATTR, though the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood. Transthyretin plays a complex role in the coagulation cascade, contributing to the activation and regulation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation, cardiac mechanical dysfunction, and atrial myopathy in patients with ATTR may contribute to thrombosis, though such events may also occur in patients with a normal sinus rhythm and rarely in properly anticoagulated patients. Haemorrhagic events are modest and mainly linked to perivascular amyloid deposits with consequent capillary fragility and coagulation anomalies, such as labile international-normalised ratio during anticoagulant therapy.

- thromboembolic events

- bleeding events

- transthyretin amyloidosis

1. Introduction

2. Interactions between Transthyretin and the Coagulation System

3. Thrombotic Events in Transthyretin Amyloidosis

4. Bleeding Events in Transthyretin Amyloidosis

4.1. Spontaneous Bleeding Manifestations: Case Reports

4.2. Bleeding While Undergoing DOACs vs. VKAs

4.3. Type of Haemorrhagic Events According to Anticoagulant Therapy

4.4. Amyloid Angiopathy Associated with an Increased Fragility of Blood Vessels

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm12206640

References

- Muchtar, E.; Dispenzieri, A.; Magen, H.; Grogan, M.; Mauermann, M.; McPhail, E.D.; Kurtin, P.J.; Leung, N.; Buadi, F.K.; Dingli, D.; et al. Systemic amyloidosis from A (AA) to T (ATTR): A review. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 289, 268–292.

- Rapezzi, C.; Merlini, G.; Quarta, C.C.; Riva, L.; Longhi, S.; Leone, O.; Salvi, F.; Ciliberti, P.; Pastorelli, F.; Biagini, E.; et al. Systemic cardiac amyloidoses: Disease profiles and clinical courses of the 3 main types. Circulation 2009, 120, 1203–1212.

- Merlini, G.; Dispenzieri, A.; Sanchorawala, V.; Schönland, S.O.; Palladini, G.; Hawkins, P.N.; Gertz, M.A. Systemic immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 38.

- Stelmach-Gołdyś, A.; Zaborek-Łyczba, M.; Łyczba, J.; Garus, B.; Pasiarski, M.; Mertowska, P.; Małkowska, P.; Hrynkiewicz, R.; Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P.; Grywalska, E. Physiology, Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiac Light Chain Amyloidosis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 911.

- Porcari, A.; Fontana, M.; Gillmore, J.D. Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 118, 3517–3535.

- Falk, R.H.; Comenzo, R.L.; Skinner, M. The systemic amyloidoses. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 898–909.

- Quarta, C.C.; Kruger, J.L.; Falk, R.H. Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circulation 2012, 126, e178–e182.

- González-López, E.; Gallego-Delgado, M.; Guzzo-Merello, G.; de Haro-Del Moral, F.J.; Cobo-Marcos, M.; Robles, C.; Bornstein, B.; Salas, C.; Lara-Pezzi, E.; Alonso-Pulpon, L.; et al. Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2585–2594.

- Laptseva, N.; Rossi, V.A.; Sudano, I.; Schwotzer, R.; Ruschitzka, F.; Flammer, A.J.; Duru, F. Arrhythmic Manifestations of Cardiac Amyloidosis: Challenges in Risk Stratification and Clinical Management. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2581.

- Frustaci, A.; Verardo, R.; Russo, M.A.; Caldarulo, M.; Alfarano, M.; Galea, N.; Miraldi, F.; Chimenti, C. Infiltration of Conduction Tissue Is a Major Cause of Electrical Instability in Cardiac Amyloidosis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1798.

- Browne, R.S.; Schneiderman, H.; Kayani, N.; Radford, M.J.; Hager, W.D. Amyloid heart disease manifested by systemic arterial thromboemboli. Chest 1992, 102, 304–307.

- Mangione, P.P.; Verona, G.; Corazza, A.; Marcoux, J.; Canetti, D.; Giorgetti, S.; Raimondi, S.; Stoppini, M.; Esposito, M.; Relini, A.; et al. Plasminogen activation triggers transthyretin amyloidogenesis in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 14192–14199.

- Bouma, B.; Maas, C.; Hazenberg, B.P.C.; Lokhorst, H.M.; Gebbink, M.F.B.G. Increased plasmin-α2-antiplasmin levels indicate activation of the fibrinolytic system in systemic amyloidoses. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5, 1139–1142.

- Wieczorek, E.; Ożyhar, A. Transthyretin: From Structural Stability to Osteoarticular and Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2021, 10, 1768.

- Mutimer, C.A.; Keragala, C.B.; Markus, H.S.; Werring, D.J.; Cloud, G.C.; Medcalf, R.L. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and the Fibrinolytic System: Is Plasmin a Therapeutic Target? Stroke 2021, 52, 2707–2714.

- Zamolodchikov, D.; Berk-Rauch, H.E.; Oren, D.A.; Stor, D.S.; Singh, P.K.; Kawasaki, M.; Aso, K.; Strickland, S.; Ahn, H.J. Biochemical and structural analysis of the interaction between β-amyloid and fibrinogen. Blood 2016, 128, 1144–1151.

- Yaprak, E.; Kasap, M.; Akpinar, G.; Islek, E.E.; Sinanoglu, A. Abundant proteins in platelet-rich fibrin and their potential contribution to wound healing: An explorative proteomics study and review of the literature. J. Dent. Sci. 2018, 13, 386–395.

- Jensen, S.B.; Hindberg, K.; Solomon, T.; Smith, E.N.; Lapek, J.D., Jr.; Gonzalez, D.J.; Latysheva, N.; Frazer, K.A.; Braekkan, S.K.; Hansen, J.B. Discovery of novel plasma biomarkers for future incident venous thromboembolism by untargeted synchronous precursor selection mass spectrometry proteomics. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 1763–1774.

- Zinellu, A.; Mangoni, A.A. Serum Prealbumin Concentrations, COVID-19 Severity, and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 638529.

- Takahashi, R.; Ono, K.; Ikeda, T.; Akagi, A.; Noto, D.; Nozaki, I.; Sakai, K.; Asakura, H.; Iwasa, K.; Yamada, M. Coagulation and fibrinolysis abnormalities in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Amyloid 2012, 19, 129–132.

- Nicol, M.; Siguret, V.; Vergaro, G.; Aimo, A.; Emdin, M.; Dillinger, J.G.; Baudet, M.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Villesuzanne, C.; Harel, S.; et al. Thromboembolism and bleeding in systemic amyloidosis: A review. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 11–20.

- Vilches, S.; Fontana, M.; Gonzalez-Lopez, E.; Mitrani, L.; Saturi, G.; Renju, M.; Griffin, J.M.; Caponetti, A.; Gnanasampanthan, S.; De Los Santos, J.; et al. Systemic embolism in amyloid transthyretin cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 1387–1396.

- Martini, N.; Sinigiani, G.; De Michieli, L.; Mussinelli, R.; Perazzolo Marra, M.; Iliceto, S.; Zorzi, A.; Perlini, S.; Corrado, D.; Cipriani, A. Electrocardiographic features and rhythm disorders in cardiac amyloidosis. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, S1050-1738(23)00024-5.

- Bandera, F.; Martone, R.; Chacko, L.; Ganesananthan, S.; Gilbertson, J.A.; Ponticos, M.; Lane, T.; Martinez-Naharro, A.; Whelan, C.; Quarta, C.; et al. Clinical Importance of Left Atrial Infiltration in Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 17–29.

- Dubrey, S.; Pollak, A.; Skinner, M.; Falk, R.H. Atrial thrombi occurring during sinus rhythm in cardiac amyloidosis: Evidence for atrial electromechanical dissociation. Heart 1995, 74, 541–544.

- Garcia-Pavia, P.; Rapezzi, C.; Adler, Y.; Arad, M.; Basso, C.; Brucato, A.; Burazor, I.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Damy, T.; Eriksson, U.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis: A position statement of the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1554–1568.

- Mumford, A.D.; O’Donnell, J.; Gillmore, J.D.; Manning, R.A.; Hawkins, P.N.; Laffan, M. Bleeding symptoms and coagulation abnormalities in 337 patients with AL-amyloidosis. Br. J. Haematol. 2000, 110, 454–460.

- Schrutka, L.; Avanzini, N.; Seirer, B.; Rettl, R.; Dachs, T.; Duca, F.; Binder, C.; Dalos, D.; Eslam, R.B.; Bonderman, D. Bleeding events in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2122.

- Ono, R.; Kajiyama, T.; Miyauchi, H.; Kobayashi, Y. Periorbital ecchymosis and shoulder pad sign in transthyretin amyloidosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e242614.

- Jhawar, N.; Reynolds, J.; Nakhleh, R.; Lyle, M. Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis presenting with spontaneous periorbital purpura: A case report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2023, 7, ytad108.

- Yumoto, S.; Doi, K.; Higashi, T.; Shimao, Y.; Ueda, M.; Ishihara, A.; Adachi, Y.; Ishiodori, H.; Honda, S.; Baba, H. Intra-abdominal bleeding caused by amyloid transthyretin amyloidosis in the gastrointestinal tract: A case report. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 15, 140–145.

- Jayakrishnan, T.; Kamran, A.; Shah, D.; Guha, A.; Salman Faisal, M.; Mewawalla, P. Senile Systemic Amyloidosis Presenting as Hematuria: A Rare Presentation and Review of Literature. Case Rep. Med. 2020, 2020, 5892707.

- Su, G.; Chen, X.W.; Pan, J.L.; Li, H.; Xie, B.; Cai, S.J. Clinical features of retinal amyloid angiopathy with transthyretin Gly83Arg variant. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 16, 128–134.

- Hudson, J.L.; Schwartz, S.G.; Davis, J.L. An 82-year-old woman with retinal vascular sheathing and vitreous hemorrhage. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2023, 17, S36–S40.

- Mitrani, L.R.; De Los Santos, J.; Driggin, E.; Kogan, R.; Helmke, S.; Goldsmith, J.; Biviano, A.B.; Maurer, M.S. Anticoagulation with warfarin compared to novel oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation in adults with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: Comparison of thromboembolic events and major bleeding. Amyloid 2020, 28, 30–34.

- Bukhari, S.; Barakat, A.F.; Eisele, Y.S.; Nieves, R.; Jain, S.; Saba, S.; Follansbee, W.P.; Brownell, A.; Soman, P. Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolic Risk in Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2021, 143, 1335–1337.

- Thelander, U.; Westermark, G.T.; Antoni, G.; Estrada, S.; Zancanaro, A.; Ihse, E.; Westermark, P. Cardiac microcalcifications in transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 352, 84–91.

- Bulk, M.; Moursel, L.G.; van der Graaf, L.M.; van Veluw, S.J.; Greenberg, S.M.; van Duinen, S.G.; van Buchem, M.A.; van Rooden, S.; van der Weerd, L. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy With Vascular Iron Accumulation and Calcification. Stroke 2018, 49, 2081–2087.

- Grand Moursel, L.; van der Graaf, L.M.; Bulk, M.; van Roon-Mom, W.M.C.; van der Weerd, L. Osteopontin and phospho-SMAD2/3 are associated with calcification of vessels in D-CAA, an hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain Pathol. 2019, 29, 793–802.

- Sud, K.; Narula, N.; Aikawa, E.; Arbustini, E.; Pibarot, P.; Merlini, G.; Rosenson, R.S.; Seshan, S.V.; Argulian, E.; Ahmadi, A.; et al. The contribution of amyloid deposition in the aortic valve to calcification and aortic stenosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 418–428.