Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of global mortality, and is considered one of diseases with the most rapid growth rate in China. Dietary fat is one of the three primary nutrients of consumption; however, high fat dietary in causing CVD has been neglected in some official dietary guidelines.

- cardiovascular diseases

- high fat diet

- fatty acids

- atherosclerosis

1. Introduction

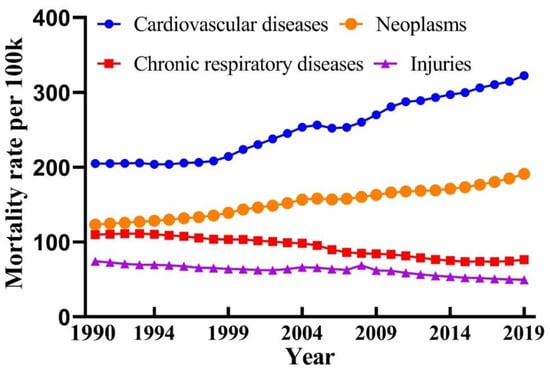

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a broad term encompassing heart and vascular diseases, and is currently the leading cause of global mortality. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were 17.9 million deaths from CVD globally in 2019, accounting for 32% of all deaths worldwide [1]. The incidence and mortality rates of CVD in developed Western countries have plateaued, owing to improvements in medical care and preventative measures, whereas the rates in developing countries, mainly China, have continued to increase rapidly. Over the past 30 years, the CVD mortality rate in China has increased from 204.78 to 322.30 per 100,000 people in 2019 (Figure 1), and the incidence rate has increased from 447.81 to 931.57 per 100,000 people, representing an alarming 108.03% increase and the fastest growth rate among all diseases [2]. In 2018, CVD accounted for more than 40% of all-cause mortality in China, ranking first among all fatal diseases [3]. These statistics highlight that CVD has become the Chinese population’s most profound and rapidly growing disease, posing a severe threat to human health.

Figure 1. Mortality rate of major diseases in China from 1990 to 2019 [2].

The most common causes of CVD incidence and mortality include ischemic heart disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure, accounting for >80% of all CVD cases globally [4]. Some of the risk factors for CVD include genetics, age, smoking, physical inactivity, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dietary habits. Notably, some of these factors, such as increased life expectancy, reduced physical activity, heightened life stress, and dietary habits have undergone profound transformations in China [5][6]. Approximately 90% of CVD cases are preventable [7], and it is essential to maintain healthy lifestyle habits to reduce the incidence and mortality of CVD.

Dietary factors play a crucial role among the various risk factors for CVD. Improving unhealthy nutritional habits is a primary approach for preventing CVD, as dietary changes are driven by individuals and are typically easier to implement and follow than other interventions. Establishing healthy dietary habits is a convenient, sustainable, and cost-effective approach. Therefore, most countries periodically release dietary guidelines to guide residents in developing healthy eating habits. The Chinese Nutrition Society published the latest edition of the “Chinese Dietary Guidelines (2022)” and the “Report on Scientific Research of Chinese Dietary Guidelines (2021)” [8][9], which cited a study published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology in 2019 by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. This study collected dietary intake data from 1982 to 2012 in China and evaluated mortality risk due to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and their related nutritional factors. The study found that high sodium intake accounted for 17.3% of the cases contributing to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases; insufficient fruit intake accounted for 11.5%; inadequate omega 3 (ω3) fatty acid such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) intake from seafood accounted for 9.7%; and low intake of vegetables, nuts, whole grains, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), and low-fat dairy products were ranked fourth and tenth, respectively [10].

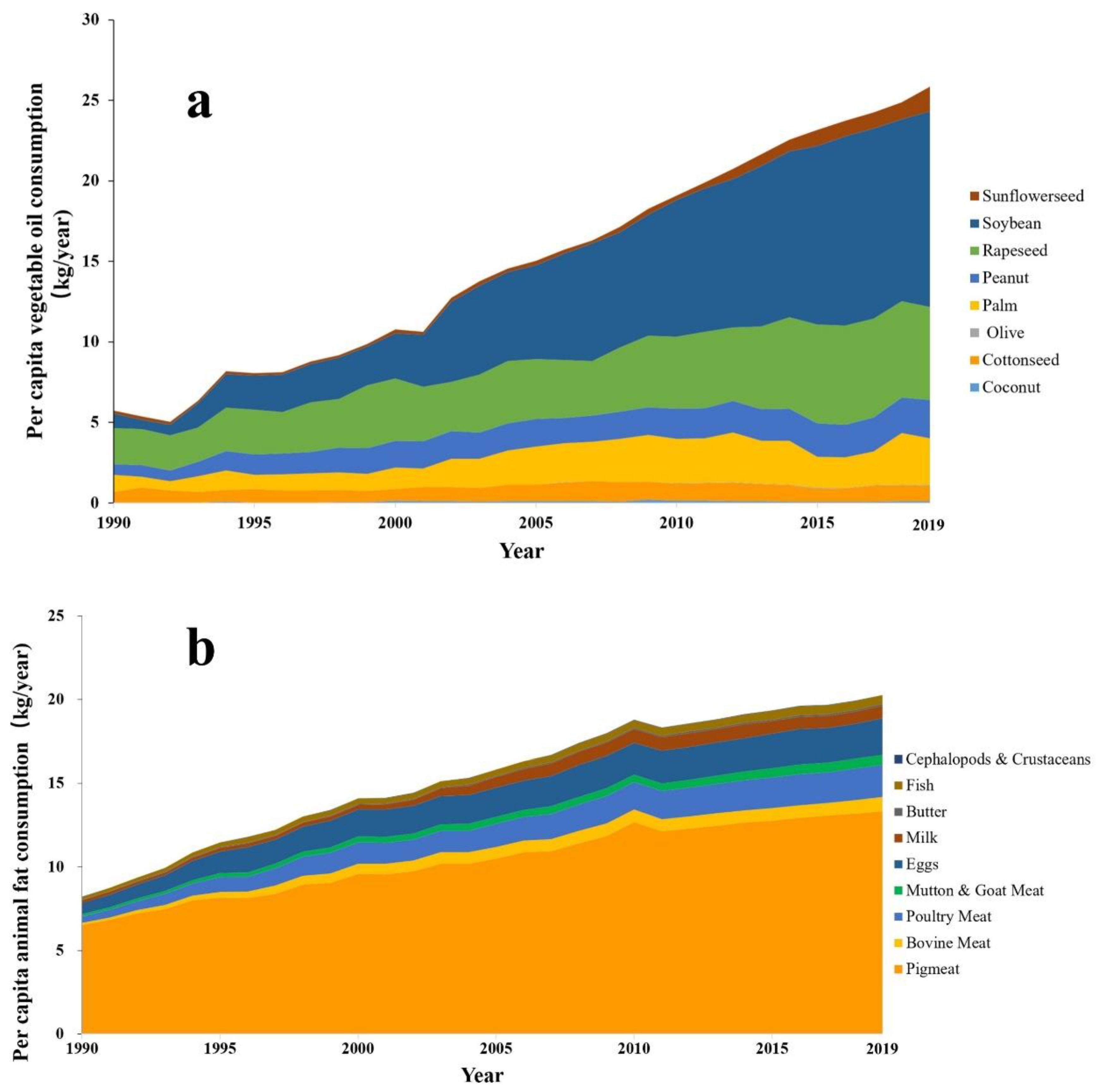

The effects of dietary fat on CVD have long been a topic of interest and debate. For instance, prior to 2000, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) restricted dietary fat intake less than 30% of total energy intake (%E). However, upon recognizing the potential hazards associated with low-fat diets, the DGA was revised in 2005 to recommend a range of 20–35%E for fat intake. Nevertheless, in 2015, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee recommended the removal of any restrictions on total fat intake [11]. To prevent the onset and death from CVD, topics are generally focused on the type of fatty acids in the diet, with little attention paid to the total fat intake [12][13]. Dietary fats can be divided into vegetable oils and animal fats. According to data from the US Department of Agriculture and the Food (USDA) and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), there has been a significant surge in oil and fat consumption in China over the last three decades, with per capita consumption of vegetable oil and animal fat increasing from 5.74 and 8.27 kg in 1990 to 25.84 and 20.56 kg as of 2019, respectively (Figure 2) [14][15].

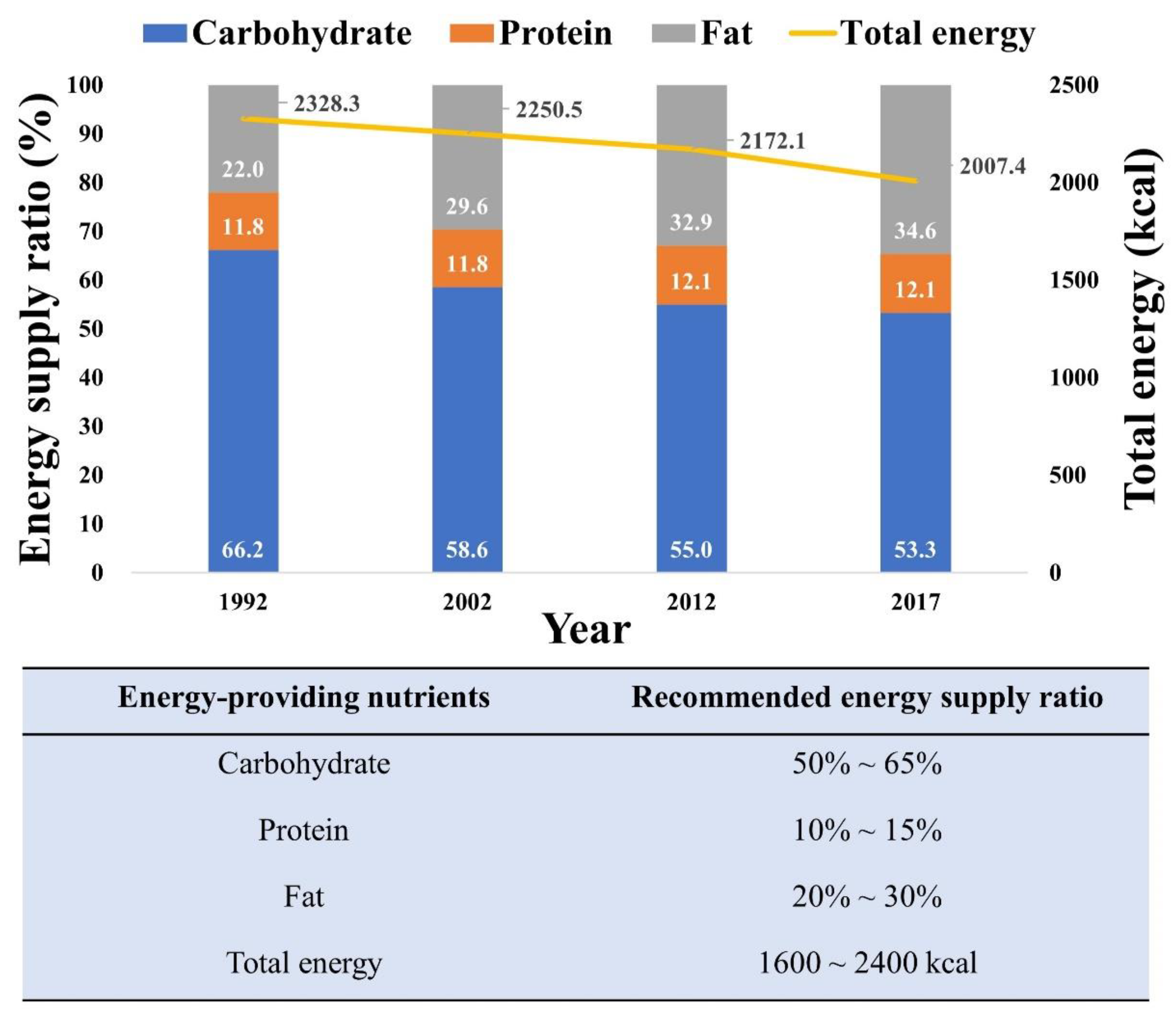

Figure 3 depicts the changes in energy supply ratios of three major nutrients and total energy intake among Chinese residents from 1992 to 2017. Over the past three decades, there has been a significant decrease in total energy intake; substantial shifts have also occurred in the energy supply ratios of the three major nutrients. These changes are primarily attributed to the reduction in overall cereal consumption. Specifically, the carbohydrate energy supply ratio decreased from 66.2% to 53.3% by 2017, while the fat energy supply ratio increased from 22% to 34.6%. Meanwhile, the protein energy supply ratio exhibited no significant variation. It is noteworthy that excessive consumption of monosaccharides, such as fructose in sugary beverages and increased consumption of sweet snacks, has emerged as an increasingly serious concern in China [16]. These dietary patterns can lead to elevated postprandial triglycerides (TG) levels, adversely impacting metabolic functions and subsequently increasing the risk of developing chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes [17][18].

Figure 3. Energy supply ratio of the 3 major nutrients and total energy intake for Chinese residents from 1992 to 2017 [8].

2. The Relationship between Dietary Patterns and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

Table 1 presents the consumption or intake of the major dietary components in China from 1990 to 2019. With a rapid economic growth in China during this period, there have been significant changes in the dietary preferences of Chinese residents. Consumption of nuts, fresh fruits, fresh dairy products, fish and shellfish, and red meat has increased, whereas consumption or intake of salt, total grains, and fresh vegetables has decreased to varying degrees.

Table 1. Migration of consumption of main dietary ingredients in China (1990 to 2019) (g/d).

| Year | 1990 | 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | 2002 | 2005 | 2010 | 2012 | 2015 | 2019 | Rate of Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salt (g) * | \ | 13.9 | \ | \ | 12.0 | \ | \ | 10.5 | 9.3 | \ | −33.1% |

| Nuts (g) ** | 2.3 | \ | 2.7 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 8.5 | 10.3 | 343.8% |

| Total cereals (g) ** | 623.0 | \ | 580.5 | 518.9 | 478.7 | 416.9 | 360.4 | 326.9 | 368.5 | 356.5 | −42.8% |

| Fresh vegetables (g) ** | 370.5 | \ | 296.1 | 300.4 | 309.3 | 299.4 | 286.8 | 271.9 | 259.9 | 260.9 | −29.6% |

| Fresh fruits (g) ** | 41.6 | \ | 61.1 | 89.0 | 91.9 | 93.6 | 101.1 | 110.4 | 110.9 | 140.7 | 238.0% |

| Fresh milk (g) ** | 5.6 | \ | 4.8 | 11.7 | 18.8 | 25.6 | 24.0 | 27.0 | 33.1 | 34.3 | 515.4% |

| Fish and shrimp (g) ** | 9.9 | \ | 13.3 | 18.5 | 18.8 | 22.5 | 27.9 | 28.8 | 30.6 | 37.2 | 277.1% |

| Red meat (g) ** | 38.6 | \ | 37.6 | 45.1 | 49.7 | 54.8 | 55.2 | 57.2 | 63.1 | 64.8 | 68.0% |

2.1. Effects of Major Dietary Factors on CVD

Sodium chloride, the primary component of table salt, is the main source of sodium intake in humans. For over a century, several researchers have conducted extensive epidemiological investigations on the relationship between salt intake and CVD in laboratory settings and clinical trials. High salt intake can lead to increased blood pressure and subsequent CVD [21]. Moreover, high salt intake affects blood pressure and causes endothelial dysfunction, stroke, ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis, arterial and ventricular sclerosis, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and heart failure, among other CVD conditions [6][22][23][24]. According to the Chinese Dietary Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1992, 2002, 2012, and 2015, the average salt intake per person in China showed a declining trend, from 13.9 g/d in 1990 to 9.3 g/d in 2015, representing a decrease of 33.1%. Although this still exceeded the recommended 5 g per day standard set by the Chinese Nutrition Society, the change in salt intake was significantly negatively correlated with CVD incidence in China (p < 0.05). Therefore, it is hypothesized that high salt intake is a key factor contributing to the onset and development of CVD. However, sodium salt intake is not the decisive factor causing the high CVD incidence in China.

Considerable evidence suggests that low fruit intake is positively associated with CVD incidence. A massive epidemiological study involving 512,891 participants was conducted to investigate the relationship between the consumption of fresh fruits and major CVDs, and the results indicated a robust logarithmic, linear dose–response relationship between the consumption of fresh fruits and both the incidence and mortality of CVD. Higher fruit consumption is associated with lower blood pressure and blood glucose levels [25]. Fresh fruit is rich in beneficial ingredients, such as polyphenols, vitamins, and minerals, which have various effects on improving all aspects of the cardiovascular system, including inhibiting platelet aggregation and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, thus preventing and treating CVD effectively by reducing blood pressure and improving blood lipids [26][27]. From 1990 to 2019, China’s per capita consumption of fresh fruit increased from 41.6 to 140.7 g, a remarkable growth rate of 238%. Although the per capita consumption of fresh vegetables has been declining annually, the total consumption of fruits and vegetables has remained unchanged over the past 30 years.

The influence of ω3 fatty acids on health and disease dates back to the 1970s, when it was discovered that the Inuit people, who mainly consumed meat, had significantly lower rates of CVD than those in other regions. Subsequent studies concluded that the Inuit diet’s high intake of DHA and EPA was responsible for this outcome [28][29]. Extensive evaluation has been conducted on the relationship between ω3 fatty acid intake and chronic diseases, including CVD. Consuming sufficient quantities of ω3 fatty acids has beneficial effects on multiple conditions. Thus, several authoritative international organizations recommend eating fish at least twice weekly to supplement ω3 fatty acids and reduce CVD risk. As shown in Table 1, fish and shellfish consumption in China has increased by 277.1% over the past 30 years, but this has not decreased CVD incidence or CVD-related deaths.

In addition, according to the China Statistical Yearbook, the per capita consumption of nuts, PUFA, and dairy products, which are closely related to the incidence and mortality of CVD, has doubled over the past 30 years. The consumption of vegetables, whole grains, refined grains, and red meat has shown varying degrees of change in the past 30 years, but has tended to stabilize after 2015 and is insufficient to explain the rapid increase in CVD incidence and mortality.

2.2. Contribution of Fat Consumption to CVD

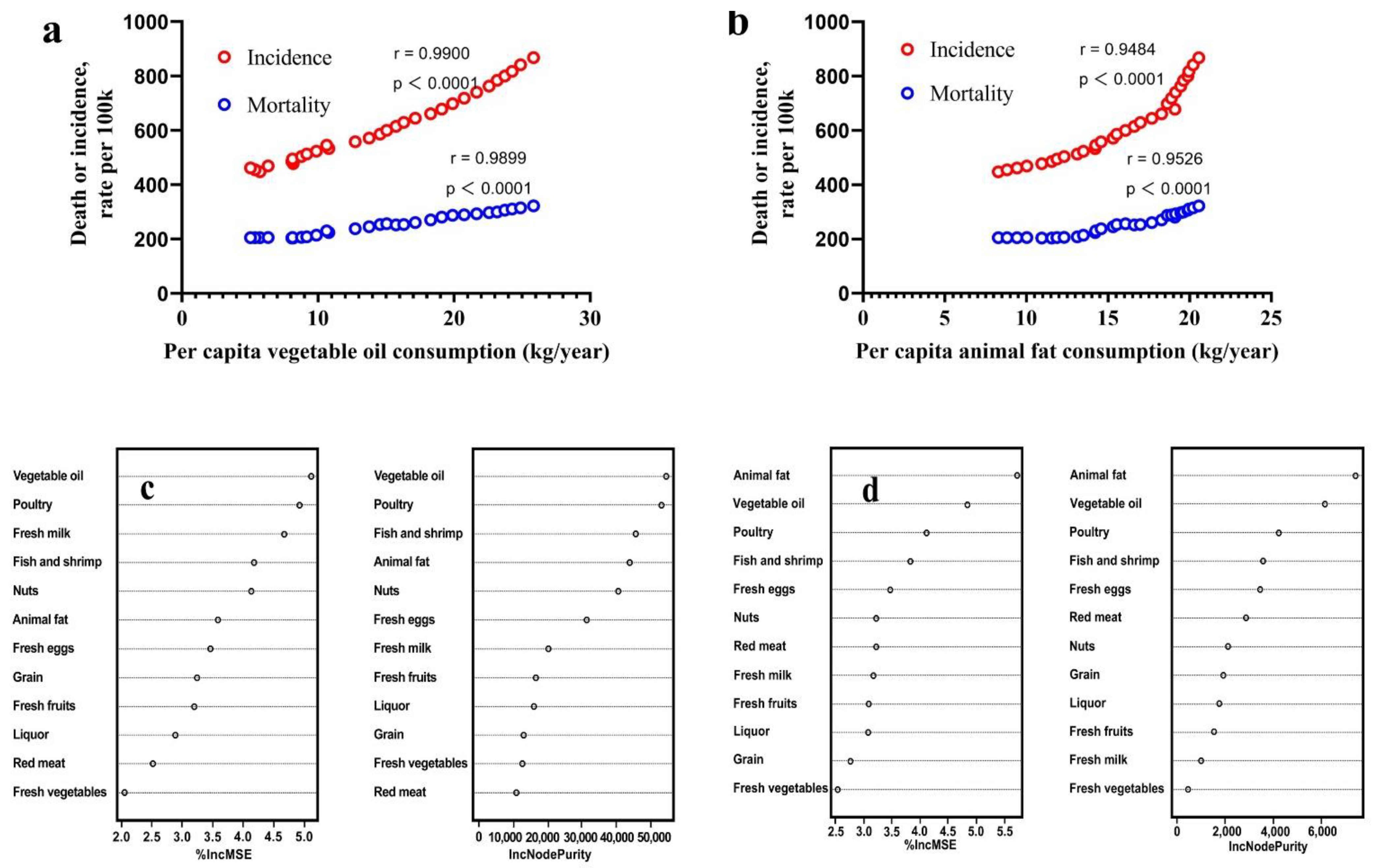

Figure 4a,b shows the linear relationship between vegetable oil and animal fat consumption in China from 1990 to 2019 with the incidence and mortality of CVD. The graph indicates a remarkably robust linear correlation (r = 0.9900, 0.9899) between the consumption of dietary fats (especially vegetable oil) in China and the CVD incidence and mortality over the past 30 years. Researchers also built a random forest machine learning model (Figure 4c,d) based on the consumption of dietary components and the incidence and mortality rates of CVD, and ranked the importance of 12 major food consumption variables. The results also indicated that dietary fat consumption considerably influenced the incidence and mortality of CVD. However, the correlation between CVD and fat intake remains controversial in the medical community, and most studies have indicated that the risk of CVD is not related to total fat intake [30][31].

Figure 4. The relationship between per capita dietary fat consumption and cardiovascular diseases in China from 1990 to 2019. (a,b) the linear relationship between per capita vegetable oil (a) and animal fat (b) consumption and cardiovascular diseases by Pearson test. (c,d) the importance ranking based on random forest influencing factors of cardiovascular diseases incidence (c) and mortality (d).

This situation in China is similar to all countries worldwide. According to the global life expectancy data released by the WHO in December 2020, Japan, Switzerland, and South Korea, which have low per capita consumption of edible oil, ranked among the top three [32], with annual vegetable oil consumptions of 17.7, 17.4, and 19.6 kg, respectively. Japan and South Korea, located in East Asia, have had cancer mortality rates surpassing CVD mortality rates in all-cause mortality since 1996 and 2001, respectively. The countries with the highest CVD incidence rates are concentrated in North America and Western Europe and, coincidentally, these countries also have the highest consumption of edible oils worldwide.

Although fat consumption cannot be equated with intake, per capita consumption and intake are positively correlated in most countries and regions. Epidemiological studies have directly demonstrated a positive correlation between high-fat diets and CVD. A meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials found that reducing dietary fat intake had little effect on all-cause mortality, but could reduce CVD mortality by 9% and CVD incidence by 16%. Moreover, the study also pointed out that as few follow-up studies last more than 2 years, reducing dietary fat intake may have a more meaningful and positive effect on CVD [33]. Another randomized controlled feeding trial involving 217 healthy young adults over 6 months indicated that a high-fat diet was associated with unfavorable changes in gut microbiota, fecal metabolomic profiles, and plasma pro-inflammatory markers, and increased the risk of CVD [34]. In addition, two low-fat diet surveys of postmenopausal women demonstrated that reducing dietary fat intake reduced the incidence and mortality of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and diabetes as carbohydrate, vegetable, fruit, and grain intake increased with no adverse effects [35][36].

For random forest analysis conditions, a thousand trees were built using R package randomForest (version 4.7–1.1), using data based on the China Statistical Yearbook (1990 to 2019), USDA, and FAO.

IncMSE, the average decrease in prediction accuracy, refers to the increase in prediction error relative to the original error when a variable is randomly permuted and the random forest model is re-estimated. The larger the IncMSE value, the more important the variable is considered to be.

IncNodePurity, the average decrease in node impurity, refers to the impact of a variable on the impurity of decision tree nodes. The larger the IncNodePurity value, the more important the variable is considered to be.

Unfortunately, because altering fat intake in the diet can change other energy sources, micronutrients, dietary fiber, and other nutritional components, it is difficult to establish a reliable and precise correlation between dietary fat and CVD. Thus, there is currently limited literature on the relationship between fat intake and CVD, particularly randomized controlled trials on fat and CVD.

Despite this, high-fat diets significantly increase systolic blood pressure, cholesterol and blood glucose levels, and body mass index, all of which are established risk factors for CVD. An indirect positive correlation between high-fat diets and CVD has also been established. A prospective epidemiological study involving 125,287 participants from 18 countries in North America, South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia found that total fat intake was associated with higher systolic blood pressure. Furthermore, fat intake is associated with elevated total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels [37]. A randomized controlled trial and meta-analysis involving 2106 participants from 20 studies demonstrated that in overweight or obese individuals without metabolic disorders, low-fat dietary interventions resulted in varying degrees of TG, TC, LDL, and high-density lipoprotein level reduction [38]. Although there is a consensus on the adverse effects of high-fat diets on the health indicators mentioned above, the relationship between dietary fat intake and CVD remains inconclusive, owing to the potential confounding effects of other nutrients, micronutrients, and dietary fiber. For instance, in 2015, the DGA in the United States recommended the removal of an upper limit for total fat intake. However, the Dietary Reference Intake for total fat intake (20–35%E) established by the National Academy of Medicine in the United States has remained unchanged since 2002. The WHO, expressing concerns about the impact of dietary fat on obesity, has continued to uphold stricter limitations on total fat intake (≤30%E) [39]. Thus, more rigorous randomized controlled trials and comprehensive meta-analyses are required to better understand the relationship between dietary fat and CVD.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu15194214

References

- WHO. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Shengshou, H. Report on cardiovascular health and diseases burden in China: An updated summary of 2020. Chin. Circ. J. 2021, 36, 521–545.

- Mc Namara, K.; Alzubaidi, H.; Jackson, J.K. Cardiovascular disease as a leading cause of death: How are pharmacists getting involved? Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2019, 8, 1–11.

- Joseph, P.; Leong, D.; McKee, M.; Anand, S.S.; Schwalm, J.-D.; Teo, K.; Mente, A.; Yusuf, S. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease, part 1: The epidemiology and risk factors. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 677–694.

- Baldo, M.P.; Rodrigues, S.L.; Mill, J.G. High salt intake as a multifaceted cardiovascular disease: New support from cellular and molecular evidence. Heart Fail. Rev. 2015, 20, 461–474.

- O’Donnell, M.J.; Chin, S.L.; Rangarajan, S.; Xavier, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Rao-Melacini, P.; Zhang, X.; Pais, P.; Agapay, S.; et al. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): A case-control study. Lancet 2016, 388, 761–775.

- Ding, G.; Sun, C.; Yang, Y. Scientific Research Report on Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents; Chinese Nutrition Society: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Chinese Nutrition Society. Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents 2022; People’s Health Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 3. ISBN 9787117314046.

- He, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Hemler, E.C.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; He, L. The dietary transition and its association with cardiometabolic mortality among Chinese adults, 1982–2012: A cross-sectional population-based study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 540–548.

- Mozaffarian, D.; Ludwig, D.S. The 2015 US Dietary Guidelines: Lifting the Ban on Total Dietary Fat. JAMA 2015, 313, 2421–2422.

- Hu, F.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C. Types of Dietary Fat and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Critical Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2001, 20, 5–19.

- Wang, D.D.; Hu, F.B. Dietary fat and risk of cardiovascular disease: Recent controversies and advances. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 423–446.

- FAO. FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 24 December 2022).

- USDA. Market and Trade Data. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/app/index.html#/app/advQuery (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Rebello, S.A.; Koh, H.; Chen, C.; Naidoo, N.; Odegaard, A.O.; Koh, W.-P.; Butler, L.M.; Yuan, J.-M.; van Dam, R.M. Amount, type, and sources of carbohydrates in relation to ischemic heart disease mortality in a Chinese population: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 53–64.

- Stahel, P.; Xiao, C.; Lewis, G.F. Control of intestinal lipoprotein secretion by dietary carbohydrates. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2018, 29, 24–29.

- Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Li, Q. The relationship between major food sources of fructose and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 14, 256–269.

- Chinese Nutrition Society. Chinese Dietary Guidelines 2016; People’s Health Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016.

- New Statistical Yearbooks. China Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Dahl, L.K.; Love, R.A. Etiological role of sodium chloride intake in essential hypertension in humans. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1957, 164, 397–400.

- Schmieder, R.E.; Langenfeld, M.R.; Friedrich, A.; Schobel, H.P.; Gatzka, C.D.; Weihprecht, H. Angiotensin II related to sodium excretion modulates left ventricular structure in human essential hypertension. Circulation 1996, 94, 1304–1309.

- de Souza, J.T.; Matsubara, L.S.; Menani, J.V.; Matsubara, B.B.; Johnson, A.K.; De Gobbi, J.I.F. Higher salt preference in heart failure patients. Appetite 2012, 58, 418–423.

- Safar, M.E.; Temmar, M.; Kakou, A.; Lacolley, P.; Thornton, S.N. Sodium intake and vascular stiffness in hypertension. Hypertension 2009, 54, 203–209.

- Du, H.; Li, L.; Bennett, D.; Guo, Y.; Key, T.J.; Bian, Z.; Sherliker, P.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L. Fresh fruit consumption and major cardiovascular disease in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1332–1343.

- Zheng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, T.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Effects and Mechanisms of Fruit and Vegetable Juices on Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 555.

- Zhao, C.-N.; Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Tang, G.-Y.; Li, H.-B. Fruits for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Nutrients 2017, 9, 598.

- Bang, H.; Dyerberg, J.; Nielsen, A.B. Plasma lipid and lipoprotein pattern in Greenlandic West-coast Eskimos. Lancet 1971, 297, 1143–1146.

- Dyerberg, J.; Bang, H.; Stoffersen, E.; Moncada, S.; Vane, J. Eicosapentaenoic acid and prevention of thrombosis and atherosclerosis? Lancet 1978, 312, 117–119.

- Investigators, S.; Dehghan, M.; Mente, A.; Zhang, X.; Swaminathan, S.; Li, W.; Mohan, V.; Iqbal, R.; Kumar, R.; Wentzel-Viljoen, E. Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017, 390, 2050–2062.

- Howard, B.V.; Van Horn, L.; Hsia, J.; Manson, J.E.; Stefanick, M.L.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Kuller, L.H.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Langer, R.D.; Lasser, N.L.; et al. Low-Fat Dietary Pattern and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 655–666.

- WHO. Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy, Data by Country. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.688 (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Hooper, L.; Summerbell, C.D.; Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, R.L.; Capps, N.E.; Smith, G.D.; Riemersma, R.A.; Ebrahim, S. Dietary fat intake and prevention of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review. BMJ 2001, 322, 757–763.

- Wan, Y.; Wang, F.; Yuan, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Tang, J.; Huang, T. Effects of dietary fat on gut microbiota and faecal metabolites, and their relationship with cardiometabolic risk factors: A 6-month randomised controlled-feeding trial. Gut 2019, 68, 1417–1429.

- Prentice, R.L.; Aragaki, A.K.; Howard, B.V.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Thomson, C.A.; Van Horn, L.; Tinker, L.F.; Manson, J.E.; Anderson, G.L.; Kuller, L.E. Low-fat dietary pattern among postmenopausal women influences long-term cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes outcomes. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1565–1574.

- Prentice, R.L.; Aragaki, A.K.; Van Horn, L.; Thomson, C.A.; Beresford, S.A.; Robinson, J.; Snetselaar, L.; Anderson, G.L.; Manson, J.E.; Allison, M.A.; et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and cardiovascular disease: Results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 35–43.

- Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Rangarajan, S.; McQueen, M.; Dagenais, G.; Wielgosz, A.; Lear, S.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Yi, S. Association of dietary nutrients with blood lipids and blood pressure in 18 countries: A cross-sectional analysis from the PURE study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 774–787.

- Lu, M.; Wan, Y.; Yang, B.; Huggins, C.E.; Li, D. Effects of low-fat compared with high-fat diet on cardiometabolic indicators in people with overweight and obesity without overt metabolic disturbance: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 96–108.

- Wu, J.H.; Micha, R.; Mozaffarian, D. Dietary fats and cardiometabolic disease: Mechanisms and effects on risk factors and outcomes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 581–601.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!