Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Marine & Freshwater Biology

许多藻类对一氧化碳有反应2通过诱导一氧化碳限制海水2浓缩机理(CCM)以获得足够的无机碳来满足其光合作用需求。为了评估不同藻类中CCM功能和活性的多样性,需要建立可靠的指标来测量和量化CCM的相对功能。正如Badger等人[47]所报道的那样,我们筛选出几种可能适合测量大型藻类CCM的指标。

- CO2 concentrating mechanism

- Ulva sp.

- green tide

- inorganic carbon transporters

- carbonic anhydrase

- Rubisco

1. CO2 Affinity of Photosynthesis versus Rubisco

Rubisco’s low affinity for external CO2 drove the evolution of CCMs. Therefore, one of the most useful indicators of whether a photosynthetic organism has a CCM is to compare the affinity of photosynthesis for external CO2 with the affinity of Rubisco for CO2. This approach was originally applied to higher plants, and by measuring the affinity Km (Rubisco CO2) of Rubisco extracted from photosynthetic organisms to substrate CO2, it was inferred that C3 species might require a CCM [69]. However, due to the limitation of extraction technology, the affinity determination of the photosynthetic organism Rubisco lacked accuracy. With the improvement of extraction and analysis techniques, this method has become widely used to evaluate algal CCMs. In general, the researchers measured the photosynthetic oxygen evolution rate under different inorganic carbon concentrations and used the data analysis software to fit the inorganic carbon response curve (P-C curve) by using Michaelis–Menten equation, where Km is the substrate concentration (DIC concentration) when the photosynthetic rate is half of the maximum, from which we can infer the affinity of algae photosynthesis to CO2 Km (photosynthetic CO2). Since marine algae may experience more persistent CO2 limitations than fresh- and brackish-water autotrophs, it can be assumed that the type of water environment determines the effectiveness of CCM. Comparing the in vivo photosynthesis and the in vitro carboxylation of Rubisco under ambient oxygen levels can show its ability to concentrate CO2 exceeds the level of environmental CO2 [70]. For example, C. reinhardtii’s ratio of Km (photosynthetic CO2) to Km (Rubisco CO2) is approximately 1:30, and that of Ulva sp. is about 5–10:68 [1,71,72]. Both apparently rely on CCM to improve the efficiency of Rubisco, whereas other algae with close specific gravity may not use CCM.

2. Effects of CA Inhibitors

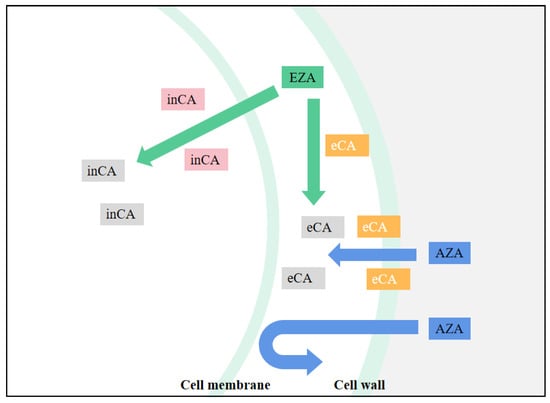

Because CA is central in all chloroplast CCM models, determining the effect of CA inhibitors is useful in studying the functional aspects of algal CCM. This is especially true for chloroplast-penetrating inhibitors, such as EZA (Ethoxzolamide), which are likely to inhibit most forms of internal CA. EZA is often used to obtain low inorganic carbon affinity for photosynthesis of algae. If the algae showed low inorganic carbon affinity under the action of EZA, it is proved that there is intracellular CA-mediated CCM in the algae, but no effect may not be conclusive evidence of CCM deletion. For CA inhibitors that cannot penetrate cell membranes, such as AZA (Acetazolamide), only apply to inhibit the activity of external CA [47], the effect on the function of chloroplast CCM is less easily explained. By comparing the relative effects of EZA and AZA, the relative contributions of internal and external CA forms to photosynthetic Ci absorption can be determined (Figure 3). For example, in the study of Gao et al. [73], after adding AZA the net photosynthetic rate of U. linza decreased, and the inhibition rate was noted to be 26.26%. Compared with AZA, EZA demonstrated a higher inhibition rate of photosynthesis (75.19%), which indicated that the internal CA contributed more to the absorption of photosynthesis. Xu et al. [74] found that U. linza and U. prolifera have obvious extracellular and intracellular CA activity by using different CA inhibitors. However, extracellular CA enzyme activity itself accelerates the mutual conversion between HCO3− and CO2 but cannot affect the CO2 equilibrium concentration, and CO2 mainly enters the cell through passive diffusion. This indicates that HCO3−-utilization in this manner does not function well at high pH (pH > 9.4) because the equilibrium concentration of CO2 is low. It is obvious that in addition to the extracellular CA catalytic utilization of HCO3−, there must be another means of using HCO3− in U. prolifera.

图3.CA抑制剂作用示意图。inCA 表示细胞内 CA,eCA 表示细胞外 CA,当 CA 图标为灰色时,CA 被抑制。

3. 使用HCO3−作为光合底物

HCO的功能3−在光合作用中被认为是藻类的一种特性[75]。HCO的利用3−藻类取决于外部CA和质膜转运蛋白的参与[76,77,78]。HCO的使用3−与 CCM 的存在密切相关。然而,一些大型藻类不仅能够利用HCO3−作为碳源,一些人已经证明了一氧化碳的使用2在特定情况下。通过检测δ13C同位素在石莼和石莼中,发现当环境CO浓度2很高,使用HCO有生理转变3−几乎完全主要使用一氧化碳2.在当前的海水中 pCO2,许多大型藻类使用HCO3−而不是溶解的一氧化碳2并利用CA转换HCO3−到 CO2供鲁比斯科使用[79,80,81,82]。例如,Mercado等人[83]发现,在当前的海水CO下2水平,叶绿素植物刚性狸藻和压缩狸藻不能获得足够的CO 2仅通过扩散吸收;因此,必须使用CCM来获得HCO3−.然而,大型藻类可能会下调其CCM,降低HCO3−使用,并变得依赖一氧化碳2作为CO时的主要碳源2浓度高[1,84,85,86]。因此,当使用这些指标评估石莼属的CCM时,HCO的使用可能会减少3−在某些情况下,仍然存在CCM活动,但有一定程度的下调。

4. 与外部Ci的亲和力的变化取决于生长Ci条件

当外部环境中存在Ci限制时,Ci转运蛋白对外部CO的亲和力2和 HCO3−增加,细胞内和细胞外CA活性也增加。两者共同作用,使微藻对外部Ci的亲和力增加了10倍以上[76]。这种可诱导的变化似乎是蜂窝基础设施参与供应一氧化碳的有力证据。2到叶绿体中的鲁比斯科。这些诱导CCM不仅限于微藻,而且在许多大型藻类中也观察到,包括石莼[1],格拉西拉里亚[87],卟啉[88]和墨角[89]。也就是说,一些藻类在面对外部Ci周期约束时可能具有诱导CCM来满足其环境需求,而其他藻类可能没有这种灵活的排列。

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jmse11101911

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!