Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Migraine ranks among the most prevalent neurological conditions, is a major cause of socio-economic and health problems worldwide, and affects approximately 12% of the population. Repeated migraine attacks can make sufferers physically, mentally, and socially incapacitated for several days. Nutrition and dietary triggers may be an important factor in migraine prevention since it is known that migraine attacks can be triggered by certain dietary compounds.

- migraine

- nutrition

- dietary triggers

- dietary compounds

- elimination diets

- ketogenic diet

- probiotics

1. Nutrition and Dietary Triggers

It is well known that in the treatment of several disorders, e.g., obesity [61] and metabolic syndrome [62], personalized or precision nutrition (PN) is used. PN establishes dynamic and comprehensive nutritional guidance based on personal differences, including genetics, metabolic profile, microbiome, physical activity, health status, food environment, dietary pattern, and socioeconomic and psychosocial features. The pathomechanism of migraine can be linked to metabolic endocrine disorders and metabolic processes [63,64], so PN may work as a promising supplementary therapy for migraine in the future.

Potential Dietary Triggers in Migraine

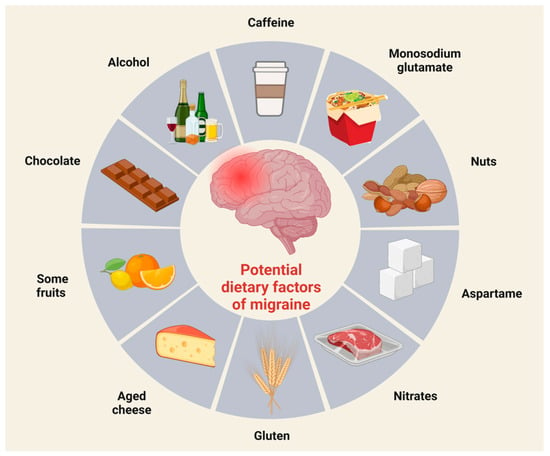

Many dietary compounds are known as potential migraine triggers, which can influence the frequency of attacks depending on the individual (Figure 1) [65,66].

Figure 1. Potential dietary factors of migraine. Scientific evidence suggests that certain foods can trigger migraine attacks. Common migraine-triggering foods include chocolate, coffee, and red wine.

The reaction of patients to these above-mentioned ingredients depends on genetic factors, quantity, and time of exposure [65], with most experiment findings concerning monosodium glutamate, caffeine, and alcohol.

Monosodium glutamate is a flavor enhancer and can be found in canned and frozen foods, salad dressings, soups, snack foods, ketchup, and barbecue sauces [67]. Based on literature data, monosodium glutamate might be a migraine trigger in high concentrations and dissolved in liquids, but not as a component of solid foods [68], which proves that it is not possible to generalize and say that one ingredient can provoke migraine attacks in every form and in every patient.

The other often-mentioned compound in association with migraine is caffeine, known for its ability to eliminate or provoke attacks. In combination with aspirin and acetaminophen, caffeine is a highly efficient pain killer. On the other hand, it is well known that caffeine withdrawal can initiate migraine attacks in caffeine users [69]. Regarding caffeine, people must pay attention to their dosage, as we know that low amounts of caffeine (~200 mg per day) have no unsafe effects contribute to decreasing the symptoms of depression [70]. Based on the literature data, we have inconclusive results concerning the connection between caffeine and migraine frequency. Some research data show that different headaches, migraine, and chronic daily headaches are more common in caffeine users than in people who do not consume this substance [71]. In contrast, other observations indicate that there is no association between headache, migraine frequency, and caffeine consumption [72].

Another substance that is the focus of attention when it comes to migraine prevention is alcohol. Ethanol can stimulate meningeal nociceptors in the trigeminal ganglion, triggering pain signals that are then transmitted in the spinal trigeminal nucleus to the thalamic nuclei, and finally to the somatosensory cortex [73]. Other mechanisms may also be involved, e.g., the vasodilator effect, dehydration, toxicity, etc. [74]. In addition to alcohol, alcoholic beverages also contain certain compounds (the byproducts of alcohol fermentation) that can trigger migraine attacks [73]. Hindiyeh and her colleagues have shown in an exceptional systematic review that alcohol consumption is one of the most common causes of migraine attacks, and the most frequently mentioned alcoholic drink is red wine [27].

Numerous studies have proposed an association between chocolate consumption and headaches, yet the precise physiological mechanisms responsible remain unclear [20,75]. One possible explanation for why chocolate triggers migraine attacks may be that the flavanols in it stimulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity, which can lead to vasodilation through increased nitric oxide (NO) production [76]. However, the results are contradictory [77,78]. Another possible cause is 5-HT. It is well known, that the concentration of 5-HT increases during a migraine attack. Moreover, 5-HT and its precursor tryptophan were found in chocolate. It is possible that by increasing 5-HT levels, chocolate consumption can trigger a migraine attack. However, there are many studies that support the beneficial effects of chocolate [78,79,80,81]. Chocolate contains many vitamins and minerals (for example, magnesium and riboflavin) that are recommended for migraine prevention [81]. Furthermore, Cady and colleagues discovered that a diet enriched with cocoa prevented inflammatory reactions in trigeminal ganglion neurons by suppressing the expression of CGRP [77].

Tyramine, an amine compound derived from the amino acid tyrosine, is present in various food items, including aged cheeses, cured meats, smoked fish, beer, fermented foods, and yeast extract, among others [82]. Tyramine has the potential to trigger headaches by promoting the release of norepinephrine and exerting an agonistic influence on α-adrenergic receptors [83].

Aspartame is an artificial sweetener. Several studies suggest that it causes various neurological or behavioral symptoms; in addition, its use can cause headaches, especially in people who consume moderate or high doses (900–3000 mg/day) for a long time [84,85,86].

Based on the above, recognizing and avoiding dietary migraine triggers is essential, as it can help reduce the frequency of migraines, allowing migraineurs to gain control over a condition that leaves them feeling exhausted and helpless.

2. Diets

2.1. Elimination Diets

As discussed earlier, patients are also different in what compounds can trigger an attack in them. Based on this fact, they can avoid ingredients that have provoked migraine for them already. This process is called an elimination diet. Randomized crossover studies and double-blind, randomized, crossover trials have found that elimination diets can reduce attack frequency, duration, severity, and the amount of medication required to counter these attacks [87,88]. Using this method is not guaranteed to resolve migraines, because migraine attacks are almost always multi-triggered; thus, eliminating or identifying one compound is not a failsafe way to avoid migraine. Electronic diaries and artificial intelligence might help us use big data from patients and identify headache-associated ingredients [18,87].

2.2. Migraine and Other Targeted Diets

Researchers have developed targeted migraine diets [18] that influence many “migraine-specific” areas and mechanisms of the body, namely brain mitochondrial function, neuroinflammation, NO, CGRP, or neuronal excitability [89].

Among these diets, the ketogenic diet has increasingly come into focus in the treatment of neurological disorders, including migraine, which balances severe restriction of carbohydrates with higher intakes of lipids and proteins. Ketogenic diets increase the number of ketone bodies, which has a beneficial effect on migraine prevention. Ketogenic diets and ketone bodies have roles in enhancing neuroprotection, acting against serotonergic dysfunctions, repairing mitochondrial function, suppressing neuroinflammation, and reducing CGRP levels in patients [89]. Thus, enhancing ketone bodies might have a positive effect on migraine prevention [90]. In a 2016 study, adherence to the ketogenic diet for 1 month was found to be able to decrease the frequency and duration of migraine attacks in a small group of patients [91].

Besides ketogenic diets, patients should also know about the benefits of consuming omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Balancing these acids is not only important in migraine prevention and treatment, but it is also crucial in preventing other disorders, e.g., atherosclerosis, as well. Decreasing omega-6 and enhancing omega-3 fatty acids in the body might have a positive effect in trying to reduce migraine attacks [90].

Increased blood sugar stability may benefit migraineurs [92]. In an experiment run in 2018, a low-glycemic-index diet was able to decrease attack frequency in the first month after beginning this diet [93].

Relatively recent epigenetic diets aim to influence the mechanisms of cellular structures, e.g., mitochondria or some molecules, e.g., DNA, using specific dietary ingredients. Their name came from Hardy and Tollefsboll, who have shown the possibility of dietary ingredients influencing the epigenetic system of patients with certain disorders, and that many ingredients might have a role in preventing diseases [94]. In migraine prevention and treatment, compounds that can inhibit certain mechanisms that have a role in migraine’s pathomechanism or can boost prevention should be focused on. In this regard, one of the most promising ingredients is folate or vitamin B9, which has a role in DNA methylation. A previous study has found that abnormal mitochondrial DNA methylation occurs in migraine patients [95]; thus, folate will be a target of future studies in this field. Besides folate, riboflavin, or vitamin B2, is another compound that influences mitochondrial mechanisms. In migraine patients, riboflavin intake can inhibit the development of attacks [96,97,98,99] and their duration [100], which confirms the neuroprotective effect of riboflavin. On the other hand, besides mitochondrial DNA methylation, we should focus on histone modification in chromatin, as it can influence protein and RNA production, which can be adjusted by introducing certain dietary compounds into a patient’s diet. A histone deacetylase inhibitor drug, namely valproate, is usually an effective treatment option in epilepsy and in different types of migraine [101,102], and is considered an epigenetic drug [103]; it is another future treatment option and an alternative to epigenetic diets. In addition to this, an experimental cortical CSD model has shown that CSD can induce chromatin modification in rats [104], which proves a link between migraine and histone modification. The usage of epigenetic diets requires further research, possibly with the epigenetic profiles of patients defined prior to introduction [105].

Other much-researched diets are Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), the Mediterranean Diet, and the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diet, which have not been exclusively examined in the context of migraine. The DASH diet was originally developed to counter hypertension, and focuses on the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains while refraining from sodium, sweets, or saturated fats [92]. There are few data on migraine and the DASH diet, but what we do have are positive; the diet decreases the Migraine Index, which measures the frequency and severity of the attacks, it reduces the Headache Diary Result, which shows the frequency and duration of migraine pain, and also cuts back the Migraine Headache Index Score, which surveys the frequency, the duration and the severity of attacks in women [92]. The Mediterranean Diet, which focuses on vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, olive oil, and limited animal-based meat consumption, yields similar results. The MIND Diet was originally developed for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease [106], and has very little effect on migraine pain in women [107]. Relatively new data have also shown that tryptophan-rich nutrition (flaxseed, salami, lentils, turkey, nuts, and eggs) in a healthy diet can decrease the odds of migraine attacks in migraineurs [79,108].

Tryptophan has a distinguished role in migraine’s pathomechanism, since it is also a precursor of serotonin and kynurenines. Migraine patients have attenuated levels of serotonin and tryptophan during interictal periods, and show enhanced levels of serotonin and tryptophan under ictal periods [109,110]. Besides serotonin, the other pathway produced by tryptophan is the kynurenine pathway. Abnormal concentrations of kynurenines have been described in chronic migraine patients [111] and in a nitroglycerin model of migraine in rats [112]; thus, tryptophan-rich diets might have a role in the prevention and treatment of migraine. However, this requires further investigation, as acute and chronic intake of tryptophan has produced contradictory results [113,114].

3. Pre- and Probiotics

Plenty of research data have shown that there is pivotal crosstalk between the brain and gut, as discussed earlier. The modification of gut microflora can prevent or even treat certain disorders.

Prebiotics are fermentable food ingredients that have a beneficial effect on the health of their host [115,116], and these substances serve as food for probiotics, which are usually bacteria. Usage of probiotics might be effective in neurological disorders, e.g., Parkinson’s disease [117]. Currently, there is a lack of information about the possible positive roles of pre- or probiotics and the gut–brain axis in migraine’s pathomechanism, but there are enough data to justify further research in this field. It is known that enhanced intestinal permeability and pro-inflammatory items can be found in many intestinal disorders, and these conditions might influence the trigeminovascular system, thus provoking migraine attacks [118]. The fact that some other disorders, namely allergies and asthma, are connected to migraine proves the hypothesis that inflammatory processes can contribute to migraine pathomechanism [119,120]. Adequate fiber and low-glycemic-index diets generate the production of normal gut flora and have a role in migraine prevention [25], as well. Nowadays, there is only little human data on the application of pre-and probiotics in migraine patients. In an experiment, female patients took a mixture of different strains of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus for 12 weeks, and the frequency and the applied numbers of painkillers were reduced, but the severity and duration of attacks did not change [121]. Another study has shown that application of a mixture of Bacillus, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Streptococcus strains for 8–10 weeks can decrease the severity and frequency of attacks in episodic migraine patients, and reduce the frequency, severity, duration, and the number of drugs taken per day in chronic migraine patients [122]. In one other experiment, researchers could not detect any change in migraine frequency, and drug usage after a 12-week application of a mixture of different Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus strains [123]. On the other hand, it should be noted that some Lactic acid bacteria can produce biogenic amines (e.g., histamine, tyramine), which can cause an increase or decrease in blood pressure, thus contributing to triggering headache in people [65].

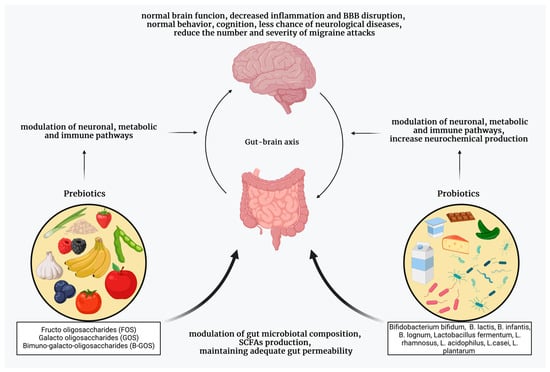

To summarize, It must be acknowledged that there is no enough data concerning the usage of pre- or probiotics in migraine prevention and treatment yet. Despite all of this, some bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus gasseri, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Streptococcus thermophilus require further study, but might prove to be a good alternative treatment in the future (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The beneficial effect of pre- and probiotics. Recently, pre-and probiotics have become the focus of migraine treatment, as the gut microbiota can influence the function of the CNS through various mechanisms. Taking pre- and probiotics can help restore and maintain a healthy gut microbiome, and can thus affect the frequency and severity of migraines. SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids, BBB, blood–brain barrier.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/neurolint15030073

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!