Positioning theory is a social theorization that aims to capture the dynamic analysis of conversations and discourses taking place in a social setting. Conversations as part of language assume interlocutors. As one engages in the interactive speech acts in the social setting, there comes the importance of interlocutors involved in these speech acts in creating a social reality, as language forms the knowledge of reality. Certain types of rights and duties can be observed in interactions between speakers and hearers in a social communicative context of interlocutors. The cluster of rights and duties, recognized in a certain social setting, can be termed as a position. One of the critical aspects is that positions are not always intentional or even conscious. Therefore, positioning theory has been redefined as a method of analysis with a focus on storylines. Storylines reveal implicit ascriptions and resistances of rights and duties through the performance of a variety of actions in a social setting where appropriateness of social acts are established and recognized by the participants engaged within the social situation. The education setting presents a dynamic situation where a variety of moral orders come into actions that set possibilities for different actors to engage in shifting positioning to accomplish certain educational actions. This entry presents the use of positioning theory in an educational setting.

Positioning theory studies the dynamics of positionings with interactive phenomena where different actors come under conversations by offering their storylines

[1][2][3]. These storylines are then shaped by discursive acts that take place within specific social practice(s). In this connection, the contextual location of positioning theory can be traced back to the communicative nature of human actions. For example, Gregory Bateson (1965; 2000)

[4][5] considers human actions as happening at different levels: individual, social and ecological. These actions could be influenced by cultural, religious and specific social practices that enable these human actions and meanings to take place. He emphasized the role of symmetry and complementarity that come into action under the mutual influence of human interactions by illustrating

Naven play under local customs in New Guinea, where the roles of men and women were reversed in the rituals (as Naven) (see Bateson, 1965)

[4]. He calls the interaction among individuals social and ecological as part of cybernetics, which goes beyond any of these three elements. The interactions among these three elements lead to the possibility of considering human actions as communicative actions. Watzlawick and Jackson (2010)

[6] consider human communication as an integral part of human sense making. They

[6] give the example of Descartes’

Cogito,

ergo sum (I think therefore I am) formula, which cannot make sense until there is a social context that creates a need to think. Thinking as an activity requires an action on the part of the other person to understand that as such. That is, human communicative actions are essentially social actions. This has been well illustrated by Jürgen Habermas (1981; 1990)

[7][8] through his thesis on the constitution of reality through communicative actions for achieving cooperation with an emancipatory intent. Of course, these communicative actions and the constitution of reality encompass both symmetric and asymmetric communications with attention to languages, social norms, customs and cultures that condition such communications. The asymmetry of communications within a social situation brings attention to the role of discursive norms and discourses that shape such actions and influence the power therein. The circulation of power and shifting points of power during communicative actions are considered to be critical in understanding the positions that different actors take within a social practice and, in turn, how linguistic structures constitute the social world.

Potter et al. (2015)

[9] identifies the importance of understanding social practice in situ in order to see how different discourses in fact create and constrain possibilities for actors to participate within discourse in communicative situations. Here, Potter and his colleagues consider the importance of assuming discourse from the constructions perspective. They suggest that social actions are embedded in multiple discourses and these discourses have three characteristics: (1) functions (goal-oriented actions); (2) construction (that actions are constructed); and (3) variations (such constructed oriented actions make such variations possible). Here, discourses instead should be looked at as interpretive repertoires orienting towards achieving social actions within a possible range of variations that the discourses make available.

Moreover, social psychology and sociology also bring insight into social actions. Here, language, socializations, norms and values embedded within cultural practices orient social actions in a particular way. For example, Butler (1988)

[10] analyzes how feminine women become through the repetitive actions and norms that format social realities, which then establishes gender roles and then re-enforces these roles through different norms and cultural practices as developed historically, politically and culturally sanctioned. Further, she points out the importance of challenging the established cultural categories as gender. Moreover, she raises the importance of understanding the effects that speech acts can bring on the particular actions of actors. John Austin (1962)

[11] performed a systematic study of speech acts in social linguistics and identified different kinds of speech acts: (1) representative, which specifies acts such as assertions, statements, claims, suggestions and hypothesis; (2) commissive, which encompasses promises, oaths and pledges; (3) directive, which includes orders, requests, invitations and challenges; (4) declarations such as baptisms, arrests and legal actions as sentencing; (5) expressive, such as greetings, congratulations, apologies, etc.; and (6) verdictive, which includes rankings, appraisings and condoning. John Searle (1995)

[12] extended this work and tried to articulate how social objects such as money become constituted through various social actions under collective intentions. In addition, collective intentions could be contrasted by individual intentions, and collective intentions cannot be reduced to individual intentions. However, individual intensions can be influenced by collective intentions.

The above research contexts with a focus on human actions, human communicative action, speech acts and the constitution of social actions through discourse and discursive acts that underpin norms, values and cultures responsible for these social actions have provided a ground on which the idea of positioning theory emerged in the 1980s. In the 1980s, the dominant influence of positivist psychology (based on survey methods or psychometric tools modeled on experimental psychology) was challenged by paying attention to the dynamic constitutions of social actions by foregrounding social practice in situ and actors’ active involvement in shaping the social reality in which they found themselves.

Within this context, this entry seeks to give an overview of the positioning theory and the implications it can have on education, while using some examples.

Assuming language as a social practice refers to a mode of action (Austin, 1962; Fairclough, 1995; 2003)

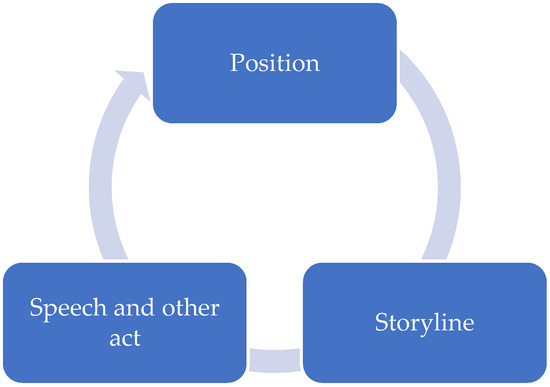

[11][13][14]. It means that social practice is always situated in the social mode of action happening in dialectical relationships where multiple actors come together to accomplish certain actions in interactive social conditions. Thus, considering any conversation with some interlocutors, this simple action implies that, through a ‘speech-act,’ we use a certain ‘storyline’ to position ourselves in the performative act of positioning. Conversational episodes are fundamental units that shape social reality and that structure social interaction. The relation between positions, speech and other acts and storylines are captured through the positioning triangle as initially proposed by Van Langenhove and Harré (1999)

[1], later adapted by McVee et al., 2011

[15] and by us recently (see

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aspects of social acts through positioning theory (inspired by the positioning triangle from McVee et al., 2011

[15]).

These three aspects (positions, speech acts and storylines) are fundamental in characterizing the complexity of social acts through positioning theory. We understand positions as something that is highly dynamic and that requires to take into consideration speech and other acts and storylines simultaneously. A more detailed explanation is provided below for each concept.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/encyclopedia3030073