Sex hormones (SHs) and their receptors (SHRs) play a crucial role in human sexual dimorphism and have been traditionally associated with hormone-dependent cancers like breast, prostate, and endometrial cancer. Research has broadened the understanding by revealing connections with other types of cancers, such as lung cancer (LC), where the androgen receptor (AR) plays a significant role.

- androgens

- nuclear receptors

- lung cancer

- non-small cell lung cancer

- testosterone

- androgen receptor

- sex-hormone receptors

- gender-related cancers

- sex steroid hormones in cancers

1. Introduction

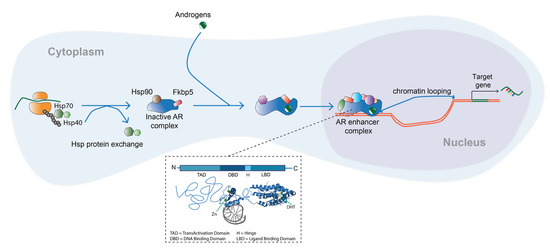

2. Androgens and the Androgen Receptor

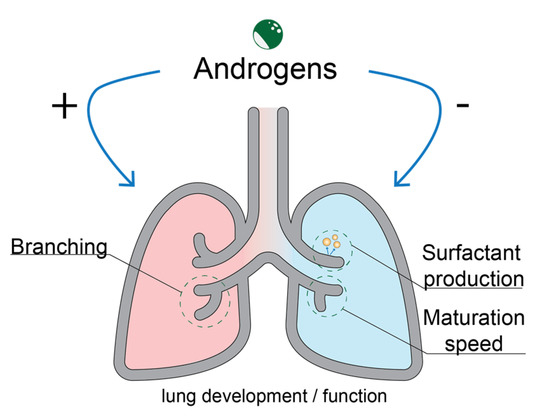

3. Role of the Androgen Receptor in Lung Development

4. Androgens and the Androgen Receptor in Lung Cancer

4.1 Androgen Receptor Signaling in Lung Cancer

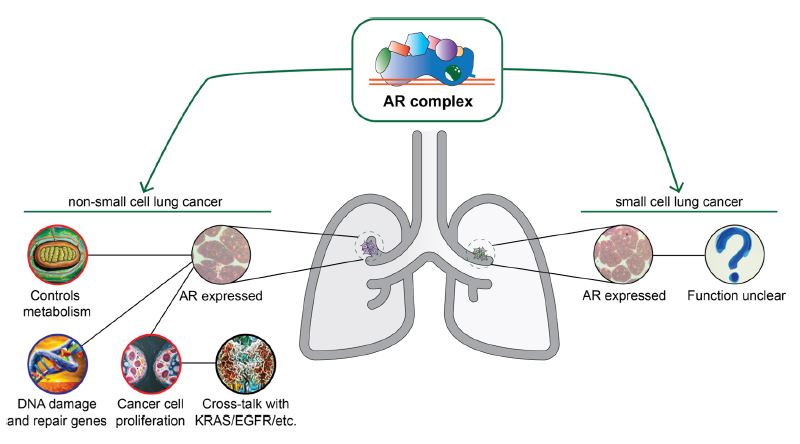

Both the functional AR protein and 5α-reductase were expressed in SCLC models [38]. AR expression was also demonstrated in NSCLC in cell lines and primary lung cancer material.[39] After this observation, studies have also demonstrated its presence in LC cell line models [40][41], while alterations were observed in 5% of LSC and AD, which further supports the view that the receptor plays a significant role in LC [42].

LC cell lines were also shown to express steroid-converting enzymes [38]. A549 cells expressed the enzyme 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) type 5 and 3α-HSD type 3, which produce steroid precursors that can activate the AR; the latter enzyme was present in a low quantity, though the cells expressed AR at a high level [38]. SH-inactivating enzymes were also detected in LC cells, mouse and human fetal lung tissue. Low 17β-HSD catalyzes the conversion of 3α-adiol to DHT and androsterone to epi-androsterone, with its downregulation linked to poor patient prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and LUAD, where it was associated with poor clinicopathological features, such as tumor size, advanced tumor stage, low tumor differentiation and poor patient prognosis [39]. It reduces radioresistance in LC cells and suppresses proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), with a potential mechanism including PTEN expression and inhibition of AKT phosphorylation [40].

Anrdogens influence cancer cells with T increasing protein synthesis rates, basal cell metabolism and energy [41]. AR in murine cells leads to upregulation of genes involved in oxygen transport and heme biosynthesis and negative regulation of genes involved in apoptosis, DNA repair and double-strand (ds) break repair (br) [41]. Research led to contrasting conclusions about the link between T and hormone-dependent cancer incidence [42].

Androgens also influence cellular processes and SPs in NSCLC. Androgen treatment changed the transcriptional landscape in murine lung tissue and human NSCLC cell lines; in A549 cell line models, it led to upregulation of genes involved in oxygen transport and utilization and downregulation of those in DNA repair and recombination [41]. AR SP modulation elucidated a crosstalk between AR and KRAS. AR cooperates with EGFR and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in cellular processes such as differentiation, growth, chemotaxis and apoptosis [43]. AR knockdown (kd) in NSCLC cell lines led to inhibition of cell proliferation and achorage-independent growth in vitro [44][45]. AR suppression was also linked to the SPs affecting stemness and self-renewal [44].

EGFR was also involved in DHT-induced growth stimulation of A549 LC cells and LNCaP prostate tumor cells. DHT treatment led to CD1 upregulation and cell proliferation, both of which could be mitigated by selective inhibitors or kd of AR/EGFR. Cross-talk between AR and EGFR plays a role in the progression of PCa and LC through activation of mTOR/CD1 pathway [5].

T treatment in a female NZR-GD rat LC model resulted in enhanced lung tumor formation, while the same effects could not be observed in hepatocellular and kidney epithelial tumors [46]. Similar findings came from an AR knockout (ARKO) mouse model where it resulted in reduced tumor size compared to control NNK-BaP mice [45].

4.2. Androgen Receptor as an Important Factor in Lung Cancer Biology: Evidence from Clinical Studies

A cohort study investigating total blood T levels in 3635 community-dwelling elderly men found a positive link with LC risk [14]. Performing a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) study on the same sample, researchers found that an increase in total T, equivalent to 4.87 nmol/L, significantly increased the adjusted risk of LC (HR = 1.30, 95% CI 1.06–1.60; p = 0.012). For every 1 SD (0.73 nmol/l) increase in DHT, the adjusted risk of LC increased by 29% (HR = 1.29, 95% CI 1.08–1.54; p = 0.004).[47] Smoking was not a confounding factor in either study [14][47]. Contrastingly, one prospective cohort study of 291 male and 193 female participants found no association between plasma T levels and LC risk [42].

AR expression was investigated in primary LC tissues where intra-tumor AR expression was detected in a minor fraction of primary LC tissues (18/566 cases) [48]. An immunohistochemistry-based study found no association between AR expression and OS in 136 tissue samples from tumor bank patients [11]. There was a significant correlation with outcome and SHRs in 62 patients with advanced NSCLC. Intra-tumor presence of AR, ER-α,and PgR were correlated with outcomes in advanced NSCLC patients. Patients with nuclear and cytoplasmic AR expression exhibited longer survival when compared to those not expressing the protein (49 and 45 months, respectively, vs. 19 months) — although the number of patients demonstrating nuclear AR expression was relatively low (8/62) [49]. Cytoplasm and nucleus AR expression in tumor tissues from 335 patients revealed worse outcomes with respect to disease-specific survival compared to the rest of the cohort [50].

Mutation-profile examination in cell-free DNA in plasma samples of LC patients revealed the expression of the AR p.H875Y mutation previously found in PCa and BC and associated with activation by other steroid hormones. AR +/+ mutation samples showed a higher mutational burden compared to double negative samples. The exact functional relevance of mutation in lung carcinogenesis is yet to be investigated [51].

AR was not significantly associated with locoregional control, metastases-free survival and OS in stage II/III NSCLC tumors of RT-receiving patients in a study investigating SHR expression and said parameters [3].

4.3. Targeting of the Androgen Receptor Pathway

Blocking the AR SP pharmacologically can be achieved by targeting AR or enzymes responsible for the conversion of steroid precursors into T or DHT [52]. CYP17A1 and 5-α reductase inhibitors can be used to block T-producing enzymes and prevent T conversion to DHT. Non-steroid anti-androgens can bind to AR and engage in competitive binding with T and DHT.[53] Steroidal anti-androgens can inhibit androgen action and luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion in a competitive manner, which can lead to decreased T production. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists can downregulate GnRH Rs and decrease LH and T [12].

Pharmacological targeting of the AR SP in LC was investigated in NSCLC cell lines, where its inhibition was associated with radiosensitization [44]. The expression of miR-224-5p, an exosome-secreted microRNA was detected in cancer specimens. Its overexpression led to an acceleration through the cell cycle and inhibition of apoptosis, while its inhibition led to decreased proliferative and migratory capacity of two LC cell lines. In a tumor xenograft mouse model, injection of the miRNA-overexpressing cells led to growth increase and necrotic tissue appearance in the lungs, along with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [54].

The effect of androgen pathway manipulation (APM) was investigated on survival in 3018 men diagnosed with LC; 339 individuals had used a form of APM prior to the study being conducted [12]. APM use in patients after LC diagnosis and before and after diagnosis led to better survival outcomes compared to patients with no APM use. Exposure to APM was associated with longer survival in early-stage disease and if treatment occurred after diagnosis. In late-stage disease, there was a significant effect in those exposed to APM after diagnosis (HR = 0.41, p = 0.02) and before and after diagnosis (HR = 0.54, p < 0.0001) [12].

A study investigated the effect of a proteasome-based system with proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) in LC cell lines. PROTACS harness the ubiquitin-proteasome system to degrade target proteins. An enzalutamide-based PROTAC led to a dose-dependent reduction of viability in a LC cell line model [55]. A summary of the mechanisms in which the AR complex can modulate cellular processes related to LC is shown in Figure 3.

5. Discussion

There are several points to consider when analyzing the role SHs and their receptors play in LC. Two confounding factors in clinical studies of LC patients that are inconsistently reported are patient SS and menopausal status. Nicotine can act as a double confounder as it increases unbound T in healthy men and independently increases LC incidence [14][56]. Another confounding factor can be menopausal status in female patients as NRs can crosstalk; though in an unclear mechanism [57]. Despite the numerous investigations of AR role in NSCCL, its role in SCLC is not understood or researched well enough.

A third limiting factor in studies is the collection time of blood and other biological specimens. Both factors are of crucial importance in studying T levels as the hormone exhibits diurnal variation with peaks and troughs throughout the day [59][60].

A final challenge that is posed in the performed studies includes the measurement method of T in LC. T is mostly found circulating in its bound form to albumin or the protein sex-binding hormone globulin (SBHG) and less than 2% is found in its free, bioactive form [14]. To improve hormone detection, blood-based association studies that measure free T can be performed and LC-MS/MS can be used as a precise quantification technique as opposed to immunoassays [61].

6. Conclusions

In line with the growing body of research on the role ARs play in LC, the interest in their therapeutic targeting is increasing. Further investigation at the genomic and SP level of A and AR in LC is required; this could be performed using probing methods or analyzing high-throughput datasets with the goal of identifying novel biomarkers and potential SP therapeutic targets. Additionally, investigations of post-translational modifications (PTMs) could offer insights into the biochemical regulation of the protein and pave the way for new avenues of research. With all novel findings, there is increasing hope that targeting the AR SP can provide relief for patients diagnosed with this deadly disease.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/endocrines4020022

References

- Hyuna Sung; Jacques Ferlay; Rebecca L. Siegel; Mathieu Laversanne; Isabelle Soerjomataram; Ahmedin Jemal; Freddie Bray; Msc Freddie Bray Bsc; Jacques Ferlay Me; Msc Isabelle Soerjomataram Md; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209-249, .

- Charles S. Dela Cruz; Lynn T. Tanoue; Richard A. Matthay; Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention. Clin. Chest Med. 2011, 32, 605-644, .

- Dirk Rades; Cornelia Setter; Olav Dahl; Steven E. Schild; Frank Noack; The prognostic impact of tumor cell expression of estrogen receptor-α, progesterone receptor, and androgen receptor in patients irradiated for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 2011, 118, 157-163, .

- Olga Rodak; Manuel David Peris-Díaz; Mateusz Olbromski; Marzenna Podhorska-Okołów; Piotr Dzięgiel; Current Landscape of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Histological Classification, Targeted Therapies, and Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 4705, .

- Anna Grazia Recchia; Anna Maria Musti; Marilena Lanzino; Maria Luisa Panno; Ermanna Turano; Rachele Zumpano; Antonino Belfiore; Sebastiano Andò; Marcello Maggiolini; A cross-talk between the androgen receptor and the epidermal growth factor receptor leads to p38MAPK-dependent activation of mTOR and cyclinD1 expression in prostate and lung cancer cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 603-614, .

- van Meerbeeck, J.P.; Fennell, D.A.; De Ruysscher, D.K.M.; Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet 2011, 378, 1741-1755, .

- Li-Han Hsu; Nei-Min Chu; Shu-Huei Kao; Estrogen, Estrogen Receptor and Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1713, .

- Takashi Kohno; Takashi Nakaoku; Koji Tsuta; Katsuya Tsuchihara; Shingo Matsumoto; Kiyotaka Yoh; Koichi Goto; Beyond ALK-RET, ROS1 and other oncogene fusions in lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2015, 4, 156-164, .

- Mengmeng Dou; Keyan Zhu; Zhirui Fan; Yuxuan Zhang; Xiufang Chen; Xueliang Zhou; Xianfei Ding; Lifeng Li; Zhaosen Gu; Maofeng Guo; et al. Reproductive Hormones and Their Receptors May Affect Lung Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 1425-1434, .

- Michelle A. Carey; Jeffrey W. Card; James W. Voltz; Dori R. Germolec; Kenneth S. Korach; Darryl C. Zeldin; The impact of sex and sex hormones on lung physiology and disease: lessons from animal studies. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007, 293, L272-L278, .

- Laurel Grant; Shantanu Banerji; Leigh Murphy; David E. Dawe; Craig Harlos; Yvonne Myal; Zoann Nugent; Anne Blanchard; Carla R. Penner; Gefei Qing; et al. Androgen Receptor and Ki67 Expression and Survival Outcomes in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Horm. Cancer 2018, 9, 288-294, .

- Craig Harlos; Grace Musto; Pascal Lambert; Rashid Ahmed; Marshall W. Pitz; Androgen Pathway Manipulation and Survival in Patients with Lung Cancer. Horm. Cancer 2015, 6, 120-127, .

- Faris Azzouni; Alejandro Godoy; Yun Li; James Mohler; The 5 Alpha-Reductase Isozyme Family: A Review of Basic Biology and Their Role in Human Diseases. Adv. Urol. 2011, 2012, 1-18, .

- Zoë Hyde; Leon Flicker; Kieran A. McCaul; Osvaldo P. Almeida; Graeme J. Hankey; S.A. Paul Chubb; Bu B. Yeap; Associations between Testosterone Levels and Incident Prostate, Lung, and Colorectal Cancer. A Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2012, 21, 1319-1329, .

- Yi X. Chan; Bu B. Yeap; Dihydrotestosterone and cancer risk. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2018, 25, 209-217, .

- Alejandro Godoy; Elzbieta Kawinski; Yun Li; Daizo Oka; Borislav Alexiev; Faris Azzouni; Mark A. Titus; James L. Mohler; 5α‐reductase type 3 expression in human benign and malignant tissues: A comparative analysis during prostate cancer progression. Prostate 2010, 71, 1033-1046, .

- Anna Grazia Recchia; Anna Maria Musti; Marilena Lanzino; Maria Luisa Panno; Ermanna Turano; Rachele Zumpano; Antonino Belfiore; Sebastiano Andò; Marcello Maggiolini; A cross-talk between the androgen receptor and the epidermal growth factor receptor leads to p38MAPK-dependent activation of mTOR and cyclinD1 expression in prostate and lung cancer cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 603-614, .

- Marina Kulik; Melissa Bothe; Gözde Kibar; Alisa Fuchs; Stefanie Schöne; Stefan Prekovic; Isabel Mayayo-Peralta; Ho-Ryun Chung; Wilbert Zwart; Christine Helsen; et al. Androgen and glucocorticoid receptor direct distinct transcriptional programs by receptor-specific and shared DNA binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 3856-3875, .

- Faisal Rahman; Helen C. Christian; Non-classical actions of testosterone: an update. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 18, 371-378, .

- Rachel A Davey; Mathis Grossmann; Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside.. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2016, 37, 3-15, .

- Rachel A Davey; Mathis Grossmann; Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside.. Clin. Biochem. Rev 2016, 37, 3-15, .

- Kristine M. Wadosky; Shahriar Koochekpour; Androgen receptor splice variants and prostate cancer: From bench to bedside. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 18550-18576, .

- S. Wach; H. Taubert; M. Cronauer; Role of androgen receptor splice variants, their clinical relevance and treatment options. World J. Urol. 2019, 38, 647-656, .

- S. Prekovic; T. Van Den Broeck; L. Moris; E. Smeets; F. Claessens; S. Joniau; C. Helsen; G. Attard; Treatment-induced changes in the androgen receptor axis: Liquid biopsies as diagnostic/prognostic tools for prostate cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 462, 56-63, .

- Chao Hu; Dan Fang; Haojun Xu; Qianghu Wang; Hongping Xia; The androgen receptor expression and association with patient's survival in different cancers. Genom. 2019, 112, 1926-1940, .

- Chawnshang Chang; Soo Ok Lee; Ruey-Sheng Wang; Shuyuan Yeh; Ta-Min Chang; Androgen Receptor (AR) Physiological Roles in Male and Female Reproductive Systems: Lessons Learned from AR-Knockout Mice Lacking AR in Selective Cells1. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 89, 21-21, .

- G. C. Shukla; A. R. Plaga; E. Shankar; S. Gupta; Androgen receptor‐related diseases: what do we know?. J. Androl. 2016, 4, 366-381, .

- Marianthi Breza; Georgios Koutsis; Kennedy’s disease (spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy): a clinically oriented review of a rare disease. J. Neurol. 2018, 266, 565-573, .

- C Chang; S O Lee; S Yeh; T M Chang; Androgen receptor (AR) differential roles in hormone-related tumors including prostate, bladder, kidney, lung, breast and liver. Oncogene 2013, 33, 3225-3234, .

- Yangsik Jeong; Yang Xie; Woochang Lee; Angie L. Bookout; Luc Girard; Gabriela Raso; Carmen Behrens; Ignacio I. Wistuba; Adi F. Gadzar; John D. Minna; et al. Research Resource: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Potential of Nuclear Receptor Expression in Lung Cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 1443-1454, .

- Tommy Seaborn; Marc Simard; Pierre R. Provost; Bruno Piedboeuf; Yves Tremblay; Sex hormone metabolism in lung development and maturation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 729-738, .

- Eric Boucher; Pierre R. Provost; Julie Plante; Yves Tremblay; Androgen receptor and 17β-HSD type 2 regulation in neonatal mouse lung development. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 311, 109-119, .

- Cesare Patrone; Tobias N. Cassel; Katarina Pettersson; Yun-Shang Piao; Guojun Cheng; Paolo Ciana; Adriana Maggi; Margaret Warner; Jan-Åke Gustafsson; Magnus Nord; et al. Regulation of Postnatal Lung Development and Homeostasis by Estrogen Receptor β. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 8542-8552, .

- H. C. Nielsen; Testosterone Regulation of Sex Differences in Fetal Lung Development. null 1992, 199, 446-452, .

- Y. Kimura; T. Suzuki; C. Kaneko; A. D. Darnel; J. Akahira; M. Ebina; T. Nukiwa; H. Sasano; Expression of androgen receptor and 5α-reductase types 1 and 2 in early gestation fetal lung: a possible correlation with branching morphogenesis. Clin. Sci. 2003, 105, 709-713, .

- Y. Kimura; T. Suzuki; C. Kaneko; A. D. Darnel; J. Akahira; M. Ebina; T. Nukiwa; H. Sasano; Expression of androgen receptor and 5α-reductase types 1 and 2 in early gestation fetal lung: a possible correlation with branching morphogenesis. null 2003, 105, 709-713, .

- Elizabeth A. Townsend; Virginia M. Miller; Y. S. Prakash; Sex Differences and Sex Steroids in Lung Health and Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 1-47, .

- P. R. Provost; Androgen Formation and Metabolism in the Pulmonary Epithelial Cell Line A549: Expression of 17 -Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 5 and 3 -Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 3. Endocrinol. 2000, 141, 2786-2794, .

- Lei Lv; Yujia Zhao; Qinqin Wei; Ye Zhao; Qiyi Yi; Downexpression of HSD17B6 correlates with clinical prognosis and tumor immune infiltrates in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 1-24, .

- Didier Auboeuf; Eric Batsché; Martin Dutertre; Christian Muchardt; Bert W. O’malley; Coregulators: transducing signal from transcription to alternative splicing. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 18, 122-129, .

- Laura Mikkonen; Päivi Pihlajamaa; Biswajyoti Sahu; Fu-Ping Zhang; Olli A. Jänne; Androgen receptor and androgen-dependent gene expression in lung. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 317, 14-24, .

- D. D ØRsted; B. G. Nordestgaard; S. E. Bojesen; Plasma testosterone in the general population, cancer prognosis and cancer risk: a prospective cohort study. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 712-718, .

- Sylwia Jančík; Jiří Drábek; Danuta Radzioch; Marián Hajdúch; Clinical Relevance of KRAS in Human Cancers. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 1-13, .

- Hsuan-Hsuan Lu; Shauh-Der Yeh; Yu-Ting Chou; Yu-Ting Tsai; Chawnshang Chang; Cheng-Wen Wu; Abstract 2126: Androgen receptor regulates lung cancer progress through modulation of OCT-4 expression. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 2126-2126, .

- Shauh-Der Yeh; Pan-Chyr Yang; Hsuan-Hsuan Lu; Chawnshang Chang; Cheng-Wen Wu; Targeting androgen receptor as a new potential therapeutic approach to battle tobacco carcinogens-induced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, A8-A8, .

- R.F.X. Noronha; C.M. Goodall; Enhancement by testosterone of dimethylnitrosamine carcinogenesis in lung, liver and kidney of inbred NZR/Gd female rats. Carcinog. 1983, 4, 613-616, .

- Yi X. Chan; Helman Alfonso; S. A. Paul Chubb; David J. Handelsman; P. Gerry Fegan; Graeme J. Hankey; Jonathan Golledge; Leon Flicker; Bu B. Yeap; Higher Dihydrotestosterone Is Associated with the Incidence of Lung Cancer in Older Men. Horm. Cancer 2017, 8, 119-126, .

- Yukinori Hattori; Akihiko Yoshida; Masayuki Yoshida; Masahide Takahashi; Koji Tsuta; Evaluation of androgen receptor and GATA binding protein 3 as immunohistochemical markers in the diagnosis of metastatic breast carcinoma to the lung. Pathol. Int. 2015, 65, 286-292, .

- Rossana Berardi; Francesca Morgese; Alfredo Santinelli; Azzurra Onofri; Tommasina Biscotti; Alessandro Brunelli; Miriam Caramanti; Agnese Savini; Mariagrazia De Lisa; Zelmira Ballatore; et al. Hormonal receptors in lung adenocarcinoma: expression and difference in outcome by sex. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 82648-82657, .

- Kaja Skjefstad; Thea Grindstad; Mehrdad Rakaee Khanehkenari; Elin Richardsen; Tom Donnem; Thomas Kilvaer; Sigve Andersen; Roy M. Bremnes; Lill-Tove Busund; Samer Al-Saad; et al. Prognostic relevance of estrogen receptor α, β and aromatase expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Steroids 2016, 113, 5-13, .

- Elena Tomeva; Olivier J. Switzeny; Clemens Heitzinger; Berit Hippe; Alexander G. Haslberger; Comprehensive Approach to Distinguish Patients with Solid Tumors from Healthy Controls by Combining Androgen Receptor Mutation p.H875Y with Cell-Free DNA Methylation and Circulating miRNAs. Cancers 2022, 14, 462, .

- Christine Helsen; Thomas Van Den Broeck; Arnout Voet; Stefan Prekovic; Hendrik Van Poppel; Steven Joniau; Frank Claessens; Androgen receptor antagonists for prostate cancer therapy. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2014, 21, T105-T118, .

- Simon Linder; Henk G van der Poel; Andries M Bergman; Wilbert Zwart; Stefan Prekovic; Enzalutamide therapy for advanced prostate cancer: efficacy, resistance and beyond. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2019, 26, R31-R52, .

- Jinbao Zhou; Hongshu Wang; Qiangling Sun; Xiaomin Liu; Zong Wu; Xianyi Wang; Wentao Fang; Zhongliang Ma; miR-224-5p-enriched exosomes promote tumorigenesis by directly targeting androgen receptor in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2021, 23, 1217-1228, .

- Lukas M. Gockel; Vladlena Pfeifer; Fabian Baltes; Rafael D. Bachmaier; Karl G. Wagner; Gerd Bendas; Michael Gütschow; Izidor Sosič; Christian Steinebach; Design, synthesis, and characterization of PROTACs targeting the androgen receptor in prostate and lung cancer models. Arch. der Pharm. 2022, 355, e202100467, .

- Katherine M. English; Peter J. Pugh; Helen Parry; Nanette E. Scutt; Kevin S. Channer; T. Hugh Jones; Effect of cigarette smoking on levels of bioavailable testosterone in healthy men. Clin. Sci. 2001, 100, 661-665, .

- Ann G. Schwartz; Geoffrey M. Prysak; Valerie Murphy; Fulvio Lonardo; Harvey Pass; Jan Schwartz; Sam Brooks; Nuclear Estrogen Receptor β in Lung Cancer: Expression and Survival Differences by Sex. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 7280-7287, .

- Susan E. Olivo-Marston; Leah E. Mechanic; Steen Mollerup; Elise D. Bowman; Alan T. Remaley; Michele R. Forman; Vidar Skaug; Yun-Ling Zheng; Aage Haugen; Curtis C. Harris; et al. Serum estrogen and tumor-positive estrogen receptor-alpha are strong prognostic classifiers of non-small-cell lung cancer survival in both men and women. Carcinog. 2010, 31, 1778-1786, .

- Michael J. Diver; Komal E. Imtiaz; Aftab M. Ahmad; Jiten P. Vora; William D. Fraser; Diurnal rhythms of serum total, free and bioavailable testosterone and of SHBG in middle‐aged men compared with those in young men. Clin. Endocrinol. 2003, 58, 710-717, .

- Donald J. Brambilla; Alvin M. Matsumoto; Andre B. Araujo; John B. McKinlay; The Effect of Diurnal Variation on Clinical Measurement of Serum Testosterone and Other Sex Hormone Levels in Men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 907-913, .

- Yi X. Chan; Helman Alfonso; S. A. Paul Chubb; David J. Handelsman; P. Gerry Fegan; Graeme J. Hankey; Jonathan Golledge; Leon Flicker; Bu B. Yeap; Higher Dihydrotestosterone Is Associated with the Incidence of Lung Cancer in Older Men. Horm. Cancer 2017, 8, 119-126, .