Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Immunology

Inflammasome complexes and their integral receptor proteins have essential roles in regulating the innate immune response and inflammation at the post-translational level. Yet despite their protective role, aberrant activation of inflammasome proteins and gain of function mutations in inflammasome component genes seem to contribute to the development and progression of human autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases.

- inflammasome

- interleukin 1

- pyroptosis

1. NLRP1

NLRP1 was the first NLR shown to form a cytosolic inflammasome complex that specifically recruits and activates a downstream caspase-1 [9]. The human NLRP1 (hNLRP1) is encoded by a single gene, differently from its murine counterpart, which instead is encoded by three paralogues (NLRP1a, NLRP1b, and NLRP1c), with the latter considered a pseudogene [10]. In addition, the expression and activation of mouse NLRP1 has been mostly studied in myeloid lineage cells, such as macrophages, whereas human NLRP1 is found to be primarily expressed at the epithelial barrier, including in keratinocytes and bronchial epithelial cells [11].

hNLRP1 is the only NLR known to undergo constitutive post-translational autoproteolysis, at position Ser1213 between the subdomains ZU5 and UPA in the FIIND [12], that results in the C-terminal (NLRP1CT) and N-terminal (NLRP1NT) portions remaining noncovalently linked. Although only a fraction of the total NLRP1 protein undergoes autoproteolysis [4], this event is essential for subsequent NLRP1 activation as the released NLRP1CT self-oligomerizes and assembles the inflammasome [12,13]. Besides FIIND autocleavage, hNLRP1 also undergoes N-terminal cleavage between the PYD and NACHT domains. Interestingly, while the N-terminal PYD is fundamental for hNLRP1 activity, it is not present in the mouse NLRP1 homolog [4]. Due to these differences between mice and humans, the results of mouse studies could only partially contribute to understanding the role of hNLRP1.

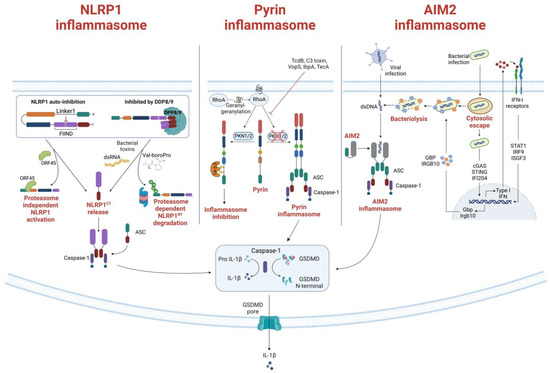

The hNLRP1 CARD motif can recruit caspase-1 directly, but the interaction can also be stabilized by the PYD-CARD adaptor protein ASC. Indeed, ASC is necessary for caspase-1 auto-processing caused by hNLRP1, but not for pyroptosis or IL-1 secretion [14]. An auto-inhibitory role has also recently been attributed to the region between the PYD and NACHT domains called Linker1; at steady state, the interaction between Linker1 and the FIIND silences hNLRP1 activation in auto-inhibitory complexes (Figure 2) [15]. Another mechanism of autoinhibition relies on dipeptidyl peptidases (DPP) 8 and 9. Because the CARD-containing NLRP1CT can activate caspase-1, CARD-containing NLRP1CT is sequestered in a ternary complex made up of full-length NLRP1 and DPP8 and/or DPP9 (Figure 2) [16,17].

Figure 2. Formation and activation of Pyrin, NLRP1 and AIM2 inflammasomes. (Left) NLRP1 inflammasome formation. Under homeostatic conditions, NLRP1 is inactivated through auto-inhibition or by binding to the inhibitor dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9 (DPP8/9). The Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus protein ORF45 is shown to bind to the Linker 1 region, lifting the auto-inhibition and DPP8/9 inhibition of NLRP1 and allowing NLRP1CT to assemble the inflammasome. Another activation mechanism of the NLRP1 is through proteasomal degradation of the NLRP1NT. When bacteria or ubiquitin ligases ubiquitinate NLRP1, NLRP1 is directed to the proteasome, where NLRP1NT is degraded, and NLRP1CT is released for inflammasome assembly. The DPP8/9 inhibitor Val-boroPro can also direct proteasomal degradation of NLRP1 and subsequent release of NLRP1CT. (Middle) Pyrin inflammasome activation mechanism. RhoA activity is induced by geranylgeranylation (mevalonate kinase pathway). Pyrin is subsequently phosphorylated by the RhoA effector kinases PKN1 and PKN2, which then bind to the inhibitory protein 14-3-3. When PKN1/2 inhibiting substances are present—i.e., TcdB, C3 toxin, VopS—or when the mevalonate kinase (MVK) pathway is not functioning correctly, PKN1/2 is inactivated and reduced pyrin phosphorylation results in the release of mature IL-1 and IL-18 from the pyrin inflammasome. The creation of the gasdermin D (GSDMD) N-terminal fragment, which forms plasma membrane pores, further promotes the release of IL-1 and IL-18. (Right) AIM2 canonical and non-canonical activation. The canonical activation, which does not involve type I interferon (IFN) activation, is induced when dsDNA is directly recognized by AIM2, triggering the inflammasome formation. On the contrary, the non-canonical activation depends on IFN activity. It is principally involved in bacterial infections that escape the vacuoles, releasing a small amount of DNA that activates cyclic-GMP-AMP synthase and IFI204. Secreted IFN exits the cells and binds to IFN receptors, driving the downstream activation and inducing bacteriolysis which releases large quantities of bacterial DNA recognized by the AIM2 inflammasome. The activated AIM2 inflammasome drives the proteolytic maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 and the maturation of GSDMD, which induces pyroptosis.

Current understanding of NLRP1 inflammasome activation is largely limited to the degradation of the NLRP1NT by the proteasome [18,19]. Direct activators, such as the B. anthracis lethal toxin, can activate NLRP1 by degrading NLRP1NT via the ubiquitin ligase UBR2, which liberates NLRP1CT for inflammasome assembly [18,19,20]. Indirect activators include the inhibitors of DPP8/9. As previously mentioned, DPP9 forms a ternary complex with full-length NLRP1 and NLRP1CT to sequester it and prevent its oligomerization [16,17,21]. The DPP8/9 inhibitor Val-boroPro weakens hNLRP1–DPP9 interaction and indirectly accelerates hNLRP1NT degradation, promoting inflammasome activation [16].

The panel of stimuli sensed by NLRP1 is expanding. For example, Bauernfried et al. discovered that NLRP1 binds directly to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) through its LRR domain [22]. In addition, Yang et al. identified the first viral protein—tegument protein ORF45—that directly binds to and activates the NLRP1 inflammasome in human epithelial or macrophage-like cell lines without the aid of the proteasome [15]. They also showed that ORF45 induces NLRP1 inflammasome activation in human epithelial or macrophage-like cell lines. Mechanistically, ORF45 binding to Linker1 displaces UPA from the Linker1–UPA complex and induces the release of the hNLRP1CT for inflammasome assembly. NLRP1 has developed the ability to sense various molecular entities or perturbations. The mechanisms by which NLRP1 senses these various modalities are more intricate than those of a promiscuous receptor, which binds to various ligands through the same ligand-binding domain and molecular mode of action. Overall, it is obvious that NLRP1 has not yet divulged all its secrets and that there is still much research to be done in this new field.

2. NLRP3

While not the first inflammasome to be discovered, NLRP3 is the most well studied due to its critical role for host immune defenses against bacterial, fungal, and viral infections [23]. NLRP3 is mainly expressed by myeloid cells (monocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells) but can also be found at the level of the central nervous system [24], and epithelium. NLRP3 is a tripartite protein that consists of a PYD, a NACHT domain and a LRR domain and can be activated through canonical, non-canonical, and alternative pathways (Figure 3). For canonical NLRP3 activation, macrophages must first be exposed to priming stimuli, such as TLR, NLR (e.g., NOD1 and NOD2), or cytokine receptor ligands. These ligands ultimately activate the NF-κB transcription factor, which, in turn, upregulates NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression, which are not constitutively expressed in resting macrophages [25,26].

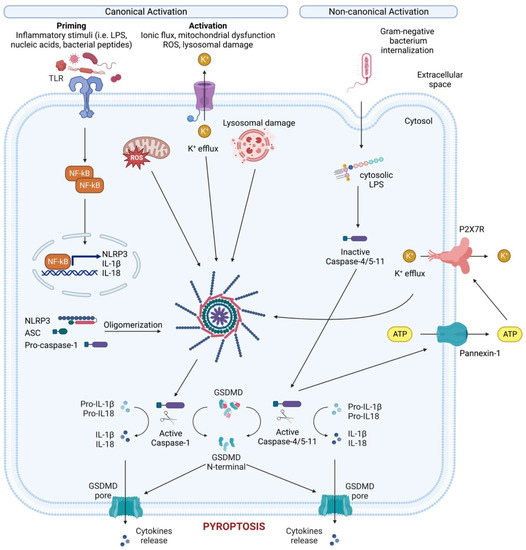

Figure 3. Canonical and non-canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation requires two steps: the priming step and the activation step. In the priming step, TLR stimulation induces the transcription and expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1 through NF-κB. Subsequently, various PAMPs and DAMPs induce the activation step by initiating numerous molecular and cellular events, including K+ efflux, mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) release, and lysosomal disruption. The NLRP3-dependent self-cleavage and activation of pro-caspase-1 self-cleavage and activation leads to the maturation of the pro-inflammatory cytokine’s interleukin 1 (IL-1) and interleukin 18 (IL-18). Additionally, gasdermin D (GSDMD) is cleaved by activated caspase-1, releasing its N-terminal domain, which then integrates into the cell membrane to create pores. These pores allow the release of cellular contents, including IL-1 and IL-18, and trigger pyroptosis, a form of inflammatory cell death. The non-canonical NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by cytosolic LPS, which directly interacts with caspase-4/5 in human (caspase-11 in mice). This interaction results in the autoproteolysis and activation of these caspases. The activated caspases subsequently open the pannexin-1 channel, allowing ATP release from the cell and activating the P2X7R, causing K+ efflux, canonical NLRP3 activation and the maturation of IL-1 and IL-18. In addition, activated caspase-4/5-11 cleaves GSDMD to cause membrane pore formation and pyroptosis, contributing to the release of IL-1 and IL-18.

Following priming, NLRP3 can be activated by diverse stimuli, including ATP, ion flux (in particular, K+ efflux) [27,28], particulate matter [29,30,31], pathogen-associated RNA [32], and bacterial and fungal toxins and components [1,33]. In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction, the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and lysosomal disruption have been proposed to be signals for the assembly and activation of inflammasomes [34]. Given that NLRP3 does not interact directly with any of these agonists and that they are biochemically distinct, it is thought that they all cause a similar cellular signal.

Most NLRP3 stimuli cause macrophages and monocytes to experience K+ efflux. In fact, IL-1 maturation and release from macrophages and monocytes in response to ATP or nigericin, which are now known to be NLRP3 stimuli, is mediated by cytosolic K+ depletion [27,35,36,37]. Additionally, K+ efflux alone was shown to activate NLRP3 in murine macrophages, and high extracellular K+ blocks NLRP3 inflammasome activation but not NLRC4 or AIM2 inflammasome activation [28,38]. It has, therefore, been assumed that diminished intracellular K+ levels can trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation [28]. Recent research, however, has found small chemical compounds—i.e., imiquimod and CL097—that activate NLRP3 independently of K+ efflux [39]. This finding suggests that either NLRP3 inflammasome activation is caused by an event downstream of K+ efflux, or that K+ efflux-independent pathways also exist for NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

During non-canonical NLRP3 activation, cytoplasmic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) directly binds the CARD of caspase-4/5/11 (which induces pyroptosis via GSDMD) and pannexin-1, a membrane channel that releases ATP (Figure 3) [40,41,42]. This extracellular ATP activates the purinergic P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) [43], an ATP-gated cation selective receptor that forms a pore in the plasma membrane that mediates K+ efflux. Besides directly causing pyroptosis, the non-canonical inflammasome also induces the canonical NLRP3 inflammasome to promote IL-1β and IL-18 maturation and release [44].

Unlike both the canonical and non-canonical pathways, the alternative inflammasome pathway does not require K+ efflux or ASC speck formation, and does not induce pyroptosis [45]. Rather, caspase-1 activation and IL-1 maturation and secretion in human monocytes is induced by LPS stimulation alone [46]. This alternative pathway requires caspase4/5, Syk activity, and Ca2+ flux instigated by CD14/TLR4-mediated LPS internalization. In murine dendritic cells, prolonged LPS exposure, in the absence of any other activating signals, resulted in NLRP3-mediated IL-1β processing and secretion independent of P2X7R [47].

NLRP3 inflammasome activation is likely regulated by various post-translational modifications, with ubiquitination and phosphorylation being the most thoroughly studied [48], as well as nitrosylation and sumoylation [49].

Several groups have demonstrated that the mitotic spindle kinase NEK7 is a crucial regulator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation [50,51]. This role of NEK7 is distinct from its function in the cell cycle, as its kinase activity is not required for NLRP3 activation [50]. According to the proposed activation model, NEK7 binding induces conformational changes to NLRP3 whereby exposed PYDs can recruit ASC leading to subsequent caspase-1 activation. Nevertheless, it was recently demonstrated that another kinase called IKKβ, which is activated during priming, causes NLRP3 to be recruited to phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P), an abundant phospholipid on the trans-Golgi network. When IKKβ recruits NLRP3 to PI4P, NEK7—previously believed to be essential for NLRP3 activation—becomes redundant.

In the past decade, intense efforts have been put into the investigation of the mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. However, much more work is needed to understand how diverse cell signaling events are integrated to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.

3. NLRP6

NLRP6 ensures microbial homeostasis, as shown in NLRP6-deficient mice that exhibit decreased IL-18 levels and dysbiosis, altering the composition of the intestinal microbial community. Indeed, NLRP6 is highly expressed in intestinal goblet cells and in lungs, liver, and tubular epithelium of kidneys. Moreover, it seems to have a role in the regulation of homeostasis in the periodontium and gingiva [52]. NLRP6 has an N-terminal PYD, a nucleotide-binding domain, and a C-terminal LRR [52]. Gram-positive, bacteria-derived lipoteichoic acid activates the NLRP6 inflammasome by binding its LRR domain and cleaves caspase-11 through the glycerophosphate repeat of lipoteichoic acid [53]. LPS also directly binds the NLRP6 monomer via its LRR, inducing conformational changes and dimerization, which, together with ASC and caspase-1, form the inflammasome complex responsible for the maturation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 [54]. NLRP6 is also involved in the anti-viral response, as seen in NLRP6-deficient mice that are more susceptible to encephalomyelitis virus infections than their wildtype counterparts [55]. This function of NLRP6 is achieved in collaboration with DHX15, which together recognize dsRNA to induce type I interferon (IFN) and IFN-stimulated gene activation via mitochondrial antiviral signaling proteins to counteract viral infections.

4. NLRP7

NLRP7 belongs to the family of signal-transducing ATPases and, to date, it has been described in humans and sheep. It has been reported that human NLRP7 is expressed in B, T, and monocytic cells, as well as in the lung, spleen, thymus, testis, and ovaries [56]. The ability of NLRP7 to form an inflammasome complex remains controversial. A study in human macrophages showed that NLRP7 can form an inflammasome complex in response to bacterial infections [57]. Specifically, mycoplasma and Gram-positive bacterial infections can activate NLRP7, which, in turn, induces IL-1β secretion. To form an inflammasome, NLRP7 requires binding and hydrolysis of ATP in its NACHT domain [58]. Moreover, complex post-translational modifications regulate its activity; namely, NLRP7 is either ubiquitinated to regulate its functions, or deubiquitinated by the STAM-binding protein to prevent its trafficking to lysosomes and its degradation [59]. Some observations also suggest that NLRP7 might have anti-inflammatory activity under certain conditions. NLRP7 can inhibit IL-1β secretion mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome without affecting NF-κB activation required for the priming [60,61]. These features have led to the hypothesis that the interaction between NLRP7, pro-caspase-1, and pro-IL-1β may inhibit pro-IL-1β maturation. Indeed, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from hydatidiform mole patients with mutations in NLRP7 exhibit reduced IL-1β secretion upon LPS treatment compared to healthy individual cells [62]. Whether these mutations are gain- or loss-of-function remains to be elucidated.

Altogether, these observations need to be better characterized to evaluate the involvement of NLRP7 in regulating inflammation. Moreover, the observation of an anti-inflammatory role in non-immune cells represents a good starting point to elucidate the mechanism that leads to NLRP7 inflammasome activation.

5. NLRP10

NLRP10 (also known as NOD8, PAN5, or PYNOD) is the only NLR lacking the characteristic LRR domain involved in protein–protein interactions, suggesting that NLRP10 might have an inflammasome-independent function. NLRP10 is expressed in various human and mouse tissues and cell types, including epithelial cells, keratinocytes, macrophages, DCs, and T cells [63]. However, the expression patterns seem to be cell-type- and context-dependent, and its function may vary depending on the cellular environment and the signaling pathways involved. Although the physiological role of NLRP10 has been largely uncharacterized, data suggest a role in the recognition and response to bacterial pathogens (Salmonella and Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and parasites (Leishmania major) [64,65,66].

Early studies showed that NLRP10 negatively regulates NF-κB activation, cell death, and IL-1β release [67], and inhibits caspase-1-mediated maturation of IL-1β [64]. Conversely, others reported normal canonical activation of NLRP3 and IL-1β production in NLRP10-deficient mouse DCs [65]. These pieces of evidence point to the possibility that NLRP10 may operate variably in different cellular environments. Indeed, Próchnicki et al. and Zheng et al. identified that the phospholipase C activator 3m3-FBS is the first trigger for NLRP10-based inflammasome assembly in colonic epithelial cells and differentiated keratinocytes [68,69]. Mechanistically, 3m3-FBS causes mitochondrial destabilization that recruits NLRP10 to damaged mitochondria, where it assembles, independently of the priming step, to form a canonical inflammasome together with ASC and caspase-1. Further research is needed to fully understand the immune and non-immune functions of NLRP10.

6. NLRP12

NLRP12 was described in 2012 as a negative regulator of the NF-κB in activated B-cell signaling, with a crucial role in controlling inflammation in both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic compartments [70]. Indeed, we now know it is expressed in bone marrow DCs, neutrophils, macrophages, and granulocytes [71]. NLRP12 negatively regulates the canonical NF-κB signaling pathways by interacting with hyperphosphorylated IRAK1, which inhibits its accumulation. On the other hand, NLRP12 dampens the non-canonical pathway by inducing the degradation of NF-κB-inducing kinase via interaction with TRAF3 [70,72,73]. One of the consequences of suppressing NFκB signaling is that macrophages do not produce the chemoattractant factor CXCL1, negatively impacting neutrophil migration and recruitment to infection sites during microbial infections [74,75,76]. Moreover, NLRP12 negatively regulates T-cell responses, as shown by the higher production of IFN-γ, IL-17, and Th2-associated cytokines in NLRP12-deficient compared to wildtype T cells [77,78].

Besides negatively regulating immune signaling, NLRP12 has been studied as an inflammasome component. For example, during Yersinia pestis infection, NLRP12 activation induces the caspase-1, IL-1β, IL-18 cascade [79]. Although the NLRP12 activation mechanisms remain unknown, NLRP12 ligand generation requires the presence of virulence-associated type III secretion systems, suggesting NLRP12 activation may involve sensing damage associated with type III secretion. However, even if NLRP12 is involved in in vivo resistance against Yersinia infection, NLRP3 activation is required in both Yersinia and Plasmodium infections, suggesting that differential NLR activation might contribute to optimal protection and host defenses [80].

7. Pyrin

Pyrin encoded by MEFV is expressed largely in granulocytes, eosinophils, and monocytes. Early structural investigations of Pyrin revealed a nuclear role, indicated by the presence of a bZIP transcription factor domain and two overlapping nuclear localization signals [81]. Although full-length Pyrin is primarily found in the cytosol, later studies looking into its localization and function discovered the colocalization of the N-terminal Pyrin fraction with microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton [82].

The Pyrin C-terminal B30.2 domain is of particular significance because most familial Mediterranean fever (FMF)-associated mutations cluster there and functional data suggest that this domain is necessary for the molecular pathways causing FMF. In vitro overexpression studies demonstrated direct interaction between caspase-1 and pyrin B30.2 but others examining the impact of FMF-related mutations on the binding affinity of B30.2 to caspase-1 produced contradictory findings [6,83].

The ligand or signals that activate Pyrin have long been unknown. In 2014, Xu et al. [84] showed that Pyrin is able to sense pathogen-induced changes in the host Rho guanosine triphosphatases (Rho GTPases) (Figure 2). For example, the Clostridium difficile virulence factor TcdB, which glycosylates and subsequently inhibits the activity of a minor Rho GTPase called RhoA, can activate the Pyrin inflammasome [85]. When exposed to wildtype TcdB, bone-marrow-derived macrophages show a potent Pyrin-mediated inflammasome response, enhanced caspase-1 activity, and pyroptosis, which does not occur upon exposure to mutant TcdB. Inhibition of RhoA is not restricted to TcdB, as other bacterial toxins also, such as C3 (Clostridium botulinum), pertussis toxin (Bordetella pertussis), VopS (Vibrio parahaemolyticus), IbpA (Histophilus somni), and TecA (Burkholderia cenocepacia), can distinctly modify the RhoA switch I region domain [86,87,88]. Due to the lack of direct interaction between Pyrin and RhoA, Pyrin is believed to be activated by an indirect signal downstream of RhoA, rather than through direct recognition of specific RhoA modifications. Given that Rho GTPases regulate many aspects of actin cytoskeleton dynamics, it is, therefore, hypothesized that changes in the cytoskeleton organization might trigger Pyrin. Moreover, Pyrin activation relies on the RhoA-dependent serine/threonine-protein kinases PKN1 and PKN2, that directly phosphorylate Pyrin at Ser208 and Ser242 [89]. As a result, the chaperone proteins 14-3-3ε and 14-3-3τ interact with phosphorylated Pyrin, preventing the development of an active inflammasome and maintaining Pyrin in an inactive state. Bacterial toxins that inactivate RhoA result in decreased PKN1 and PKN2 activity and decreased amounts of phosphorylated Pyrin, which frees pyrin from 14-3-3 inhibition and promotes the development of an active Pyrin inflammasome. Studies of the autoinflammatory disorder caused by mevalonate kinase (MVK) deficiency offered more proof that the Pyrin inflammasome regulation mechanism described there is accurate. The mevalonate pathway is an important metabolic pathway that generates several metabolites, including geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. This metabolite acts as a substrate for the geranylgeranylation of proteins, a post-translational lipid modification. RhoA is geranylgeranylated, and its translocation from the cytosol to the cellular membrane, which is required for activation, is dependent on this post-translational modification. Inhibiting the MVK pathway in bone-marrow-derived macrophages causes the release of membrane-bound RhoA and Pyrin inflammasome-dependent production of IL-1β [89]. By adding geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, or by chemically activating PKN1 and PKN2, the synthesis of IL-1 was prevented.

Recent research has identified a previously unknown regulatory and molecular connection between AIM2, Pyrin, and ZBP1, which promotes the formation of the AIM2 PANoptosome, a multiprotein complex that includes various inflammasome sensors and cell death regulators [90].

8. NLRC4

NLRC4 was first described in 2001 as an activator and recruiter of caspase-1 upon bacterial pathogen sensing. Indeed, NLRC4 combines with pro-caspase-1 via CARD–CARD interactions to induce its processing and activation [91]. Specifically, the NLRC4 CARD interacts with the ASC adaptor protein CARD, thus linking NLRC4-ASC with caspase-1 to mediate downstream signaling [92]. Indeed, the CARD domain of ASC is necessary for recruiting caspase-1 to ASC specks, ensuring correct pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 proteolytic cleavage and activation [93,94,95], thus triggering proteolytic processing and oligomerization of GSDMD leading to pyroptosis [96]. NLRC4 is mainly expressed in myeloid cells, astrocytes, retinal pigmented epithelial cells, and intestinal epithelial cells [97].

NLRC4 forms an inflammasome complex with NAIP proteins, comprising three N-terminal baculovirus IAP-repeat domains, a central NACHT, and a C-terminal LRR [8], and acts as an upstream sensor of bacterial ligands in the cytoplasm. As such, the NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasome recognizes cytoplasmic bacterial ligands (mainly Gram-negative bacteria) and induces an inflammatory response via caspase-1 activation and pyroptosis. The NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasome in human and murine macrophages is activated by flagellin [98,99,100] and the type III [101,102] or type IV secretion system [103,104] proteins through direct recognition via NAIP proteins. It has been shown in mice that IFN regulatory factor 8 is responsible for the transcriptional induction of Nlrc4 and Naip 1, 2, 5, and 6 [105]. The formation of the NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasome is quite peculiar. NLRC4 activation starts with the formation of a ligand-bound NAIP complex that changes the conformation of an NLRC4 monomer, exposing the “catalytic surface” of the active monomer, allowing it to interact with the “acceptor surface” of an inactive NLRC4 monomer. This contact activates a second monomer responsible for engaging more NLRC4 monomers, thus triggering the formation of an NLRC4 coil [7,92,106,107]. Consequently, NLRC4 oligomerization induces ASC and caspase-1 recruitment. NLRC4 inflammasome activation is finely regulated by phosphorylation and ubiquitination events [108,109].

NLRC4 was initially thought to induce inflammation by activating the caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-18 cascade and promoting GSDMD maturation. Later data showed, however, that an artificial NAIP5-NLRC4 activator can induce the release of arachidonic acid by activating the calcium-dependent phospholipase A2 [110]. Arachidonic acid, in turn, stimulates the rapid production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes. The mechanism of arachidonic acid release and its link with NLRC4 activation is still unclear; however, more than 1000 possible targets of caspase-1 have been identified that might cooperate in NLRC4 activation to activate numerous downstream signals involved in the inflammatory response [92].

9. AIM2

Unlike other inflammasome activators, dsDNA can activate an ASC-dependent, but NLRP3-independent, inflammasome, the AIM2 inflammasome [111]. AIM2 is expressed by myeloid cells, keratinocytes, and T regulatory cells [97], and it is composed of an N-terminal PYD domain and a C-terminal hematopoietic expression, IFN-inducible, and nuclear localization (HIN) domain that senses dsDNA. An HIN-dependent interaction between AIM2 and dsDNA is enabled by two, high-affinity dsDNA binding folds in the HIN domain. Under homeostatic conditions, PYD and HIN form an intramolecular complex that inhibits inflammasome activation; this inhibition is relieved when the HIN domain binds dsDNA. Hence, the PYD can interact with ASC, allowing it to polymerize and thereby activate AIM2 [5,112].

The interaction between dsDNA and the AIM2 complex is independent of the DNA sequence or its origin, but the DNA must be at least 80 base pairs long to be sensed by the HIN domain [113]. Indeed, host DNA (including mitochondrial DNA, damaged nuclear DNA, and exosome-secreted host DNA released in the cytosol) and intracellular viral and bacterial DNAs released upon microbial infections, can all trigger AIM2-dependent innate immunity [114,115,116]. The AIM2 inflammasome has canonical and non-canonical activation mechanisms (Figure 2) [117]. Canonical activation, which mostly occurs during viral infections [118], is rapid and does not involve type I IFN activation [119]. By this mechanism, dsDNA is directly recognized by AIM2, triggering the formation of the inflammasome. Non-canonical activation, conversely, depends on IFN activity and is principally involved in bacterial infections [120]. Unlike canonical activation, non-canonical activation is thought to involve intracellular bacteria that escape the vacuoles and release small amount of DNA, thereby activating cyclic-GMP-AMP synthase and IFI204, which are two components of the cascade that drive IFN secretion [121]. At this point, secreted type I IFN exits the cells where it binds IFN receptors, driving the downstream activation of immunity-related GTPase family member b10 and guanylate-binding proteins, which, in turn, induce bacteriolysis releasing large quantities of bacterial DNA that are eventually recognized by the AIM2 inflammasome [122,123]. Unlike other DNA sensors involved in IFN induction, AIM2 inflammasome assembly following detection of cytosolic dsDNA drives the proteolytic maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 and the maturation of GSDMD, which induces pyroptosis [5,124,125].

To prevent cytokine overexpression and cell death, AIM2 inflammasome activation must be tightly regulated; this regulation is achieved through PYD:PYD or CARD:CARD interactions [126]. The presence of three human PYD-only (POP) genes (POP1, POP2, and POP3) suggests that POPs may negatively regulate inflammasomes [127,128,129]. POP1 and POP2 are broad-spectrum inhibitors that interfere with inflammasome assembly by interacting with ASC PYD. Conversely, POP3 specifically inhibits AIM2 by binding to AIM2 PYD, consequently blocking the AIM2 and ASC interaction [128].

Pathogens have evolved strategies to escape AIM2 inflammasome activation. For example, the human cytomegalovirus virion protein pUL83 by interacting with AIM2 inhibits its activation [126]. Huang et al. demonstrated that THP-1-derived macrophages infected with HCMV showed increased levels of AIM2 at early stages of infections, but 24 h post-infection AIM2 decreased to basal levels. They investigated the effect of pUL83 on AIM2 in recombinant HEK293T cells expressing AIM2, ASC, pro-caspase-1, and pro-IL-1β and found that, upon induction of AIM2 activation, the expression of pUL83 led to a drastic reduction in AIM2, pro-caspase-1, and pro-IL-1β levels. These results demonstrate that pUL83 is responsible for reducing AIM2 response leading to downstream reduction of caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage [130]. Moreover, since AIM2 inflammasome becomes active every time it senses cytosolic dsDNA, some bacterial pathogens can escape AIM2 recognition by maintaining their structural integrity [131].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells12131766

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!