2. Importance of Cacti in the Semi-Arid Region

The world’s drylands cover nearly 47% of the Earth’s surface and support 39% of the world’s population [

11]. Brazil has a semi-arid land area of 1,128,697 km

2, home to approximately 27.9 million people [

12]. In this region, a primarily low-income population is recorded, where agriculture is a primary means of survival.

As climate change has already caused significant changes in the planet and agriculture makes up a significant share of environmental degradation, they are leading to the deforestation of native areas, soil disturbance, changes in the hydrological cycle, and higher carbon emissions, along with reduced rainfall and intensified drought events [

13]. These environmental changes certainly culminate in impacts on the South American dry forest biome. In this scenario, a mitigating alternative for the changes already observed is the expansion of the existing plants and their partial replacement by vegetation more suitable for arid and semi-arid regions, such as cacti [

12].

The cactus is a vital fodder resource for arid and semi-arid regions. However, in Brazil, Tunisia, South Africa, and Morocco, cactus orchards could be multipurpose, whether in human or animal food [

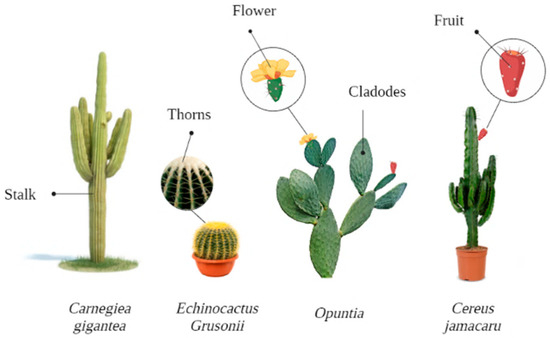

14]. Cacti are part of a group of xerophytic plants, of the

Cactaceae family, which have a wide variety of shapes and sizes (

Figure 1), including arboreal, shrubs, globular, columnar, crawlers, tall, or dwarf, and have succulent stems—which allow them to accumulate large amounts of water in their tissues—and edible fruit [

15,

16,

17].

Figure 1. Morphological diversity of the main cactus species.

The hardiness of cacti is mainly due to their crassulacean acid metabolism, known as CAM, which favors the efficient use of water, fixing carbon dioxide (CO

2) with phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP-carboxylase) during the night when water losses through transpiration are minimal [

18] (

Figure 2). This accumulation of organic acids in vacuoles overnight can reduce leaf water potential and maximize water uptake and storage, and also prevent the exchange of internal CO

2 with the external atmosphere.

Figure 2. Representation of crassulacean acid metabolism (MAC) during night and day of cactus pear.

CAM plants temporarily separate carbon fixation through PEPC (phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase) and carbon refixation through Rubisco (the first step of the Calvin–Benson cycle). When operating in CAM mode, the plant opens its stomata at night, and the diffusing CO

2 in the leaf is fixed by PEPC, with the resulting malic acid stored in vacuoles. During the day, when the stomata are generally closed, malic acid is transported out of the vacuole, decarboxylated, and the CO

2 is released again for final fixation by RubisCO [

19]. This mechanism allows CAM plants to perform photosynthesis the following day while the stomata are closed [

20]. During this process, CAM plants produce various bioactive compounds such as carboxylic acids, lignins, flavonoids, and phenols. These compounds are produced by the plant in response to environmental stresses such as water scarcity and high temperatures.

The importance of this plant is particularly evident in arid and semi-arid environments, where access to most vegetables is relatively poor, and it is mainly used as fodder in animal feed [

21]. Some species are now cultivated and evaluated for fruit production [

22]. These plants are an alternative source of vegetable food, nutritionally rich, and have potential in the social and economic development of vulnerable regions, where diversity and access to food are a challenge faced in the struggle to eradicate hunger.

Species of Brazilian cacti that are still little studied can be a source of food and components with technological properties for possible applications in the food industry, such as

Opuntia cochenillifera,

Cereus jamacaru,

Cereus hildmannianus,

Pilosocereus gounellei,

Tacinga inamoena, and

Pilosocereus pachycladus [

23]. Some species considered safe for human consumption are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1. Species of cacti and their traditional use in human nutrition.

Young cladodes are consumed fresh or cooked, as green vegetables in salads, soups, drinks, and sauces. They are considered important sources of nutrition in countries such as Mexico, where the consumption of these products is already widespread [

21]. In this scenario, valuing cactus species from the Brazilian semi-arid region as a source of food for humans contributes to alleviating the effects of climate change and increases the diversity of highly nutritious foods, especially for vulnerable populations, in addition to generating incentives for family farming and strengthening the use of agroecological practices for the production of innovative foods.

3. Contemplating an Integrative and Circular Production of Cactus Species for Human Consumption Considering the United Nations SDGs

In 2015, in response to challenges related to the global biodiversity crisis and the fact that 795 million people suffer from food insecurity, world leaders committed to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which seek, among other objectives, to eradicate hunger and global poverty by 2030 [

24]. However, the challenge of eliminating hunger by 2030 is even more significant for many countries, particularly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where, due to the economic turmoil caused by COVID-19, and in the absence of swift and effective action, more than 265 million people could become severely food-insecure [

25].

Food security comprises four interrelated dimensions: production or availability of sufficient food to meet demand, good use of food, and the stability of these factors over time [

26]. In addition, to ensure basic food security, it is necessary to understand the perception of different populations regarding food choices. The acceptance of foods that are not directly introduced into the food context of a given population reflects different perspectives on the same object of study that refer to historical, geographic, climatic, and cultural factors that directly influence the affective and cognitive interests of the population [

1].

Cacti, as a human food, have significant economic and functional potential. In Mexico, cladodes and fruits have been used as a traditional food since the Aztec Empire in more than 200 culinary preparations; in the USA and in European and Asian countries, cladodes and fruits are considered exotic; in Brazil, cacti are considered a non-alcoholic traditional food [

1]. Although social and cultural issues related to food are one of the main obstacles to developing innovative products using non-traditional food sources, valuing these products raises encouraging prospects for sustainable food production. Additionally, with the population’s growing interest in healthy foods, innovative products tend to be well accepted when presenting nutritional qualities and potential benefits to the health and well-being of consumers.

Overcoming the obstacles faced by inserting non-conventional foods into the eating habits of a population is an arduous task that requires actions to disseminate knowledge about the benefits to human nutrition and health. However, the use of cactus species in human food presents excellent possibilities for the sustainable development of agriculture, since they have advantages over other agricultural activities because of practices that mitigate, avoid, and even improve damage to the ecosystem [

27]. The commercial production of cacti, through adopting sustainable agricultural practices and circular economy strategies, presents promising potential and a solution that seeks to meet the SDGs defined by the United Nations. This is only possible with the use of renewable biological resources to transform them into high-end commodities and to conserve the value of the resources for a more extended period, with the goal of zero waste generation and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [

28]. The production of cacti for human consumption presents great potential for the use of circular economy strategies since it aims at the concept of “waste to wealth”, which gives rise to new technologies, jobs, and livelihoods, along with intrinsic benefits to the environment [

28,

29].

4. Relevant Cacti for Food Industry

Cacti are used for various purposes, including food.

Opuntia ficus-indica is a spineless cactus that has been used for almost 500 years as a fruit crop, a defensive hedge, a support for the production of cochineal dye, as a fodder crop, and as a standing buffer feed for drought periods [

30]. It is also used in erosion control and land rehabilitation, particularly in arid and semi-arid zones, and as a wildlife shelter, refuge, and feed resource [

31,

32]. Local populations use some species of cacti as a food source, such as the fruits and cladodes of

Cereus jamacaru DC. In addition, the native cactus

Opuntia monacantha has been used to obtain flour and mucilage that can be used as a hydrocolloid for various food applications. Pitaya (

Hylocereus sp.) pulp has also been used to develop ice cream [

33,

34,

35].

Table 2 presents the chemical compositions of the most relevant cacti for the food industry.

Table 2. Chemical composition of the most relevant cacti for food industry.

Cactus fruits, particularly nopal cladodes, have a higher protein content than other commonly consumed fruits. Nopal cladodes contain 1.2–2.0 g of protein per 100 g, which is higher than apples (0.3 g/100 g), oranges (1 g/100 g), and bananas (1.1 g/100 g) [

36]. This makes cactus fruits a valuable source of plant-based proteins essential for maintaining the body’s cellular structure and function. However, the protein content of this food product is lower than that of staple grains such as rice and wheat. Nopal cladodes contain 1.2–2.0 g of protein per 100 g, while dragon fruit has a protein content of 0.2–1.2 g/100 g [

37]. In comparison, rice contains 2.6 g/100 g of protein, and wheat has 12.6 g/100 g. However, the protein content in nopal cladodes and dragon fruit is significantly higher than in common vegetables such as lettuce (1.4 g/100 g) and cucumber (0.6 g/100 g) [

37].

Dragon fruit is a notable source of carbohydrates, with a concentration ranging from 8.0 to 18.0 g/100 g. This is comparable to bananas, which contain 22.8 g/100 g of carbohydrates, and higher than apples (11.4 g/100 g) and oranges (8.5 g/100 g) [

38]. This is comparable to vegetables such as potatoes, which contain 17.5 g/100 g of carbohydrates [

39]. However, the carbohydrate content in dragon fruit is understandably lower than staple grains such as rice (28.7 g/100 g) and wheat (71.2 g/100 g) [

40]. Despite this, its relatively high carbohydrate content positions dragon fruit as a potential energy source in meals.

Prickly pear fruit is a notable source of dietary fiber, with a content of 3.0–5.0 g/100 g, which surpasses the fiber content in apples (2.4 g/100 g), oranges (2.0 g/100 g), and bananas (2.6 g/100 g) [

41]. The fiber content also surpasses the fiber content in staple vegetables such as broccoli (2.6 g/100 g) and grains such as rice (0.4 g/100 g) and wheat (1.2 g/100 g) [

42].

Regarding mineral content, cactus fruits exhibit superiority over commonly consumed fruits. The calcium concentration in nopal cladodes, for example, ranges from 220 to 320 mg/100 mg, which significantly outweighs that in oranges (40 mg/100 mg), apples (6 mg/100 mg), and bananas (5 mg/100 mg) [

43]. Additionally, the calcium content in nopal cladodes (220–320 mg/100 mg) significantly surpasses common vegetables such as spinach (99 mg/100 g) and grains such as rice (28 mg/100 g) [

44]. This showcases the potential role of cacti as an abundant source of this vital mineral, contributing to bone health and muscle function.

The vitamin content in cactus fruits also warrants attention. Prickly pear fruit contains 10–40 mg/100 g of vitamin C, and Peruvian apple cactus fruit contains 5–20 mg/100 g [

36]. These concentrations are higher than that in apples (4.6 mg/100 g) but lower than oranges (53.2 mg/100 g) and bananas (8.7 mg/100 g). These findings underscore the importance of cactus fruits as a potential source of essential vitamins.

5. Functional Ingredients Derived from Cactus Species for the Food Industry

Cacti are still little explored, but they have great potential for developing innovative food products due to their bioactive components, polysaccharides, and other constituents of interest in areas related to the study and development of food, pharmacology, and biotechnology. Due to their advantages and benefits, including their ability to adapt well to arid and semi-arid environments and their nutritional values, cactus cultivars are considered a functional food for the future and a potential crop for expanding the food base, thus ensuring food safety [

21].

Table 3 summarizes cacti components and their applications in the food industry, along with health benefits.

Table 3. Summary of cacti components and their applications in the food industry.

|

Cacti Component

|

Health Benefits

|

Applications in the Food Industry

|

References

|

|

Dietary Fiber

|

Promotes gut health, supports weight management, and maintains healthy blood sugar levels.

|

Used as a natural thickening agent in sauces, soups, and bakery items. Enhances the nutritional profile of food products. Reduces calorie intake by inducing satiety.

|

[63,64,65,66,67]

|

|

Mucilage

|

Potential prebiotic benefits due to the presence of monosaccharides such as xylose.

|

Used as a thickening agent and stabilizer. Applications include the development of edible coatings, bioplastics, encapsulating agents, and gluten-free foods.

|

[23,68]

|

|

Pectin

|

Promotes gut health, aids in controlling blood sugar levels, and helps lower cholesterol levels. Potential prebiotic properties.

|

Used for its gelling, thickening, and stabilizing properties in the production of jellies, jams, marmalades, and certain types of candy. Acts as a fat substitute in baked goods to stabilize acidic protein drinks such as yogurt.

|

[69,70,71,72,73,74,75]

|

|

Polyphenols

|

Potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer properties, antihyperglycemic activity, and potential benefits in obesity, cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases, diabetes, and gastric ulcers.

|

Used as food resources and in folk medicine, potential use in nutraceutical and cosmetic industries. Serves as a source of food coloring agents and bioethanol and biogas production. Contains beneficial compounds such as lignans, sterols, esters, saponins, and alkaloids.

|

[3,22,27,50,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83]

|

|

Flavonoids

|

Anti-inflammatory, antiaging, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticancer, hepatoprotective, reproductive system protective, antiobesity, and antidiabetic effects.

|

Significant component in the formulation of functional food and drugs. Known to regulate signaling pathways (e.g., NF-kB, PI3K/AKT, MAPK).

|

[84,85,86]

|

|

Opuntia ficus-indica (Prickly pear seed oil)

|

Rich in linoleic acid and tocopherols, including vitamin E. High sterol content, particularly β-sitosterol. Strong antioxidant properties. Relatively high smoke point. Pleasant taste and aroma.

|

Used as cooking oil; a functional ingredient in food formulations such as salad dressings, dips, and spreads; and a carrier oil for other flavors and bioactive ingredients. Additionally, valuable in the cosmetic industry.

|

[87,88,89,90]

|