Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) or atopic eczema is an increasingly manifested inflammatory skin disorder of complex etiology which is modulated by both extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Immune dysregulation, barrier dysfunction, hormonal fluctuations, and skin microbiome dysbiosis are important factors contributing to AD development, and their in-depth understanding is crucial not only for AD treatment but also for similar inflammatory disorders.

- atopic dermatitis

- miroRNAs

- interactome

1. Introduction

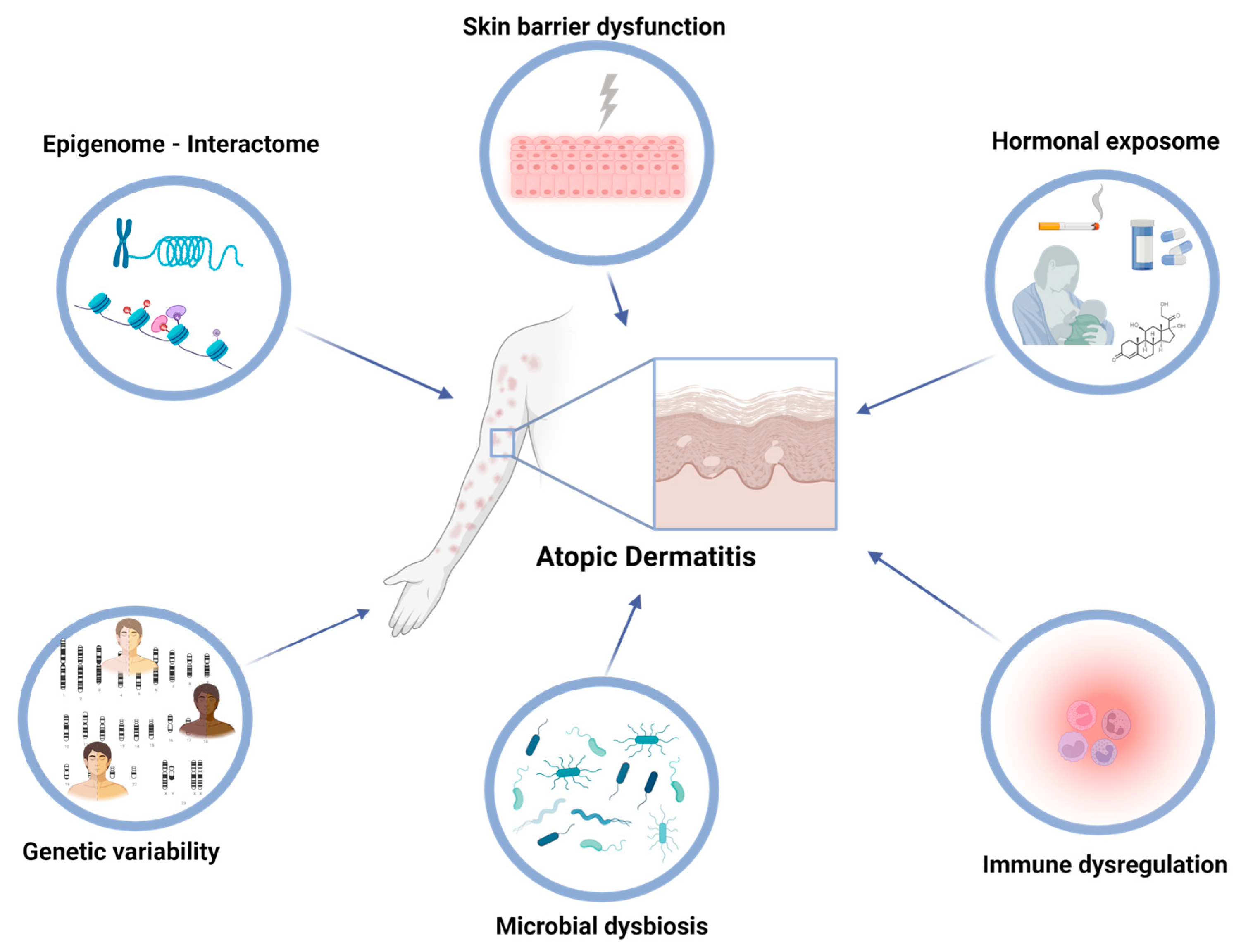

Atopic dermatitis (AD), alternatively referred to as atopic eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 10–20% of children and 1–3% of adults globally, with a growing occurrence observed in developed nations [1]. The exposome refers to the total lifetime exposures of individuals and their corresponding effects. The recent research comprehensively explored the multifaceted extrinsic exposome, incorporating environmental risk factors and mechanisms that contribute to AD [2]. However, there is growing research interest in understanding the interactions between both intrinsic and extrinsic exposomes in driving AD pathogenesis and maintenance. The intrinsic exposome refers to endogenous factors that contribute to the dysregulated inflammatory and skin barrier pathways in AD (Figure 1). Genetic variability in AD patients holds a crucial role in the disease predisposition, presenting several future opportunities for utilization as disease biomarkers [3][4]. Εxtensive research through candidate-gene approaches and genome-wide association studies (GWASs) has identified specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with AD, including genes involved in skin barrier function, immune response, and inflammation. The major example of AD-associated locus refers to the filaggrin (FLG) gene, located in the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC); loss-of-function (LOF) variants in FLG have been implicated in the impairment of skin barrier integrity, as revealed by candidate-gene approaches, and subsequently validated through GWASs [5]. Additionally, other genes encoding cytokines involved in type 2 inflammation and immune regulation, with major examples including interleukin (IL) IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, have been linked with the pathogenesis of AD and revealed as risk loci [6] (Figure 2).

Figure 1. In atopic dermatitis, immune dysregulation, barrier dysfunction, hormonal fluctuations, and alterations in the skin microbiome are key intrinsic factors that can be influenced by both genomic, epigenomic, and environmental factors.

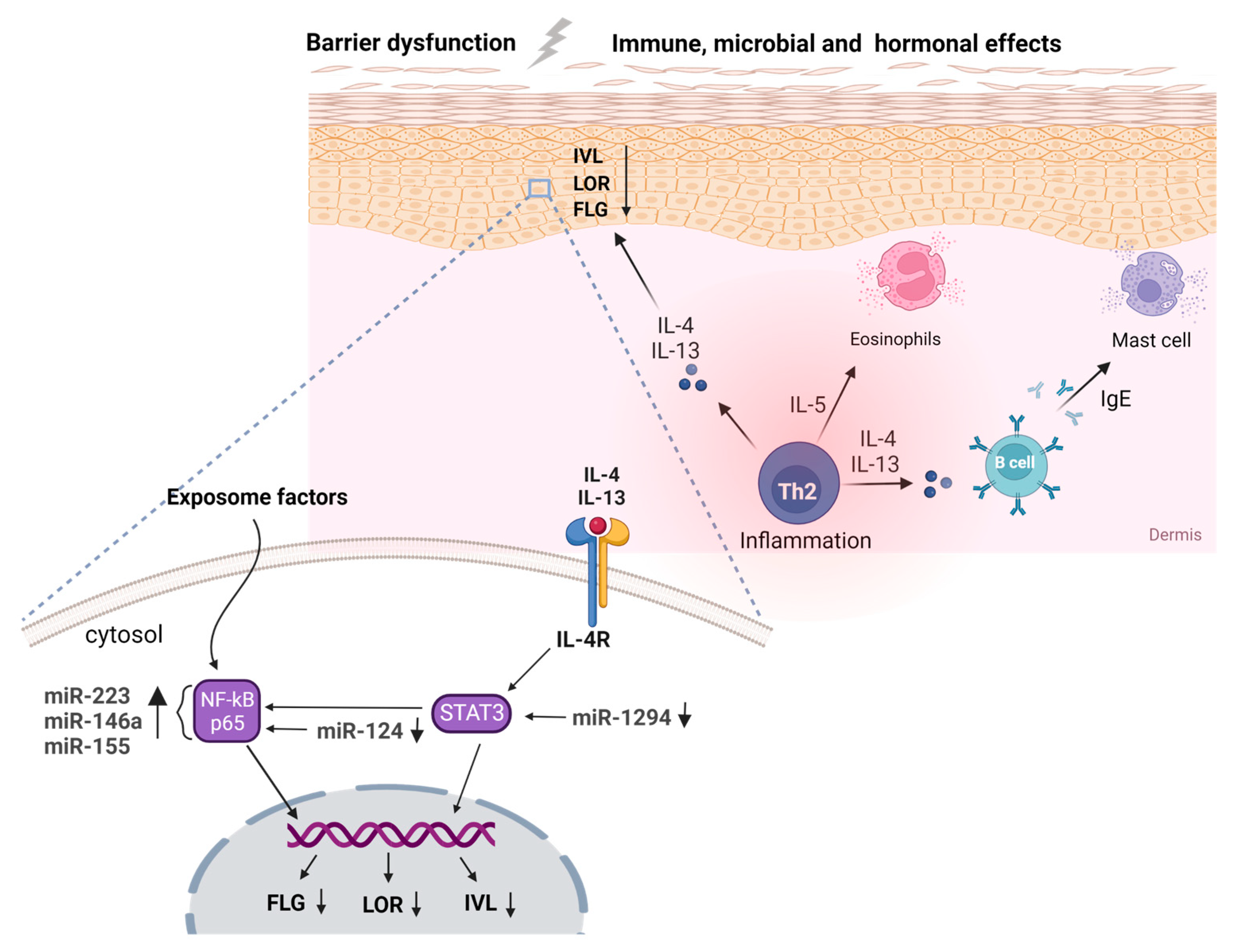

Figure 2. Genetic variations in immune-related genes, specifically those encoding cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13, have been linked to a higher susceptibility to atopic dermatitis (AD). Additionally, mutations in the filaggrin gene and other genes responsible for maintaining the integrity of the skin barrier can also contribute to the development of AD. Skin microbiome changes, including a decrease in microbial diversity and an increase in Staphylococcus aureus colonization, have also been observed and can be influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Epigenetic modifications to genes involved in these processes and microRNAs, such as miR-1294 and miR-124 via STAT3 and NF-κΒ, in a pivotal role, can further contribute to the development and progression of AD. (Created by Biorender.com (accessed on 10 May 2023)).

Apart from genetic variations, the occurrence of epigenetic modifications and disrupted expression of regulatory molecules have emerged as crucial factors governing gene expression and have been associated with the development of AD. Epigenetic modifications include reversible changes that modulate the transcriptional activity in the absence of changes in the underlying DNA sequence, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications [7]. For instance, aberrant DNA methylation patterns of genes involved in immune response and skin barrier function have been detected in patients with AD, suggesting a potential role for epigenetic modifications in the molecular mechanisms underlying the disease. Furthermore, noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as pivotal regulators of gene expression, and their implication in the pathogenesis of AD has gathered significant attention. The expanding class of ncRNAs incorporates several diverse molecules, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), with significant discrepancies in both size and related functional roles [8]. Through specific interactions with target genes, these ncRNAs modulate gene expression, exerting profound effects on cellular processes, including immune response, inflammation, and skin barrier function. The perturbed expression of such regulatory molecules has been documented in eczema patients, underscoring their potential role in disease initiation and progression.

2. Noncoding RNAs in Atopic Dermatitis

Investigating post-transcriptional modifications presents an attractive approach to understanding the intrinsic molecular interactions that occur during disease development and maintenance, which are influenced by exposure to risk factors. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), a diverse class of RNA molecules that do not encode for functional proteins, have emerged as critical regulators of the transcriptomics landscape of complex diseases with a key role in all cellular processes. The mechanism of action of ncRNAs incorporated a wide variety of post-transcriptional, epigenetic, and chromosomal modifications, with most studies focusing on miRNAs and lncRNAs.

Notwithstanding the importance of miRNAs, significant progress has been made towards the identification of novel RNA molecules with unique structures; circRNAs form a covalently closed loop structure lacking distinct, free ends that foster their prolonged half-lives compared to linear RNAs [9]. CircRNA molecules sequester miRNAs and display a sponge-like effect, as well as interact with RNA-binding proteins. Two studies have evaluated the expression profile of circRNAs in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, depicting positive correlation signals between the lesional skin biopsies of both diseases. Moldovan and colleagues were the first to explore the expression of circRNAs in lesional AD biopsies through whole transcriptome sequencing, reporting a smaller perturbed profile in eczema patients compared to psoriasis individuals; however, most deregulated circRNAs in AD were shared between both cutaneous disorders [10]. Contrastingly, expression profiling of circRNAs in the peripheral blood of eczema patients provided the under-expression of a novel circRNA, circ_0004287; functional experiments reported its anti-inflammatory mechanisms through the repression of the MALAT1 ncRNA, inhibiting the activation of M1 macrophages [11].

Various high-throughput and direct quantitative assays have been utilized to elucidate the mechanisms regulating inflammation in AD, with a particular focus on peripheral blood and related cells. Inconsistent findings were reported when comparing genome-wide miRNA levels in both serum and urine of 30 children with AD compared to 28 healthy individuals to those of lesional skin [12]. However, miR-203 and miR-483-3p were identified as potential serum biomarkers for early detection of AD, with the downregulation of miR-203 in urine samples [13]. MiR-223 was found to be upregulated in patients’ whole blood cells and is involved in hematopoietic lineage differentiation processes and platelet activation, displaying a diverse expression profile in complex diseases [14][15]. In addition, central miRNAs associated with various inflammatory disorders, such as miR-146a and miR-155, were found to exhibit their primary mechanism of action in the pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathway [16][17][18][19][20]. Interestingly, the regulatory landscape of AD shares molecular similarities with several cancer types, with over-expression of miR-151, an oncogenic miRNA that facilitates metastasis, and repression of miR-451a and miR-194-5p, suggesting potential consensus mechanisms that could serve as early, identifiable risk factors in preventive medicine [21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]. (Figure 2)

Despite the inherent differences and opposing underlying mechanisms between lesional skin and peripheral blood cells during inflammation, the pivotal regulators of inflammation, such as miR-146a, mir-223, and miR-155, persist in an upregulated profile in eczema biopsies [12][18][29][30][31][32]. However, Sonkoly et al. proved that skin-resident immune cells, particularly CD4+ CD3+ T cells, are responsible for the enhanced mir-155 signals in AD skin biopsies through immunohistochemical staining [33]. In-depth analysis of publicly available transcriptomic datasets in eczema patients has revealed several regulatory interactions, competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks that orchestrate the inflammatory response during AD pathogenesis and interactions between the expression profile of protein-coding and non-coding transcripts in AD biopsies with metabolic signatures [34][35][36][37]. Similarly to peripheral blood cells, the regulatory landscape of the cutaneous inflammation in AD shares a multitude of commonalities with the psoriasis inflammation, however, contradicting the discriminatory ability of serum miRNA levels between patients and healthy individuals [30]. Furthermore, targeted investigation of dysregulated miRNAs unveiled anti-inflammatory regulatory elements that could facilitate future therapeutic approaches. For instance, mir-124, a down-regulated molecule in AD lesional biopsies, was found to target the p65 subunit of the pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathway and subsequently reverse the cutaneous inflammation in TNF-stimulated keratinocytes [38]. Similarly, the IL-4-mediated STAT3 signaling could be repressed via the up-regulation of mir-1294, a tumor suppressor miRNA with significant participation in several cancer subtypes [39][40]. (Figure 2) Overall, studies on lesional skin have shown upregulation of miR-10a, miR-24, miR-27a, miR-29b, miR-146a, miR-151a, miR-193a, miR-199, miR-211, miR-222, miR-4207, and miR-4529-3p and downregulation of miR-135a, miR-143, miR-184, miR-194-5p, and miR-4454 [41].

3. Regulatory Interactome in Atopic Dermatitis

Interactions between the relatively stable genetic background of complex diseases with the highly variable epigenomic and regulatory profile are intricate, displaying significant implications for disease development, progression, and treatment. The genomic variability can interfere with the transcriptional activity through variants mapped in regulatory regions and subsequently quantified by expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) and mediate the methylation status of specific loci by forming novel CpG sites [42].

Sobczyk et al. conducted an integrative analysis of 103 molecular data sets, including genomics, transcriptomics, and protein QTLs, to identify causal genes and pathways that contribute to eczema pathogenesis [43]. Their pipeline prioritized genes relevant to skin and peripheral blood expression signals for further exploration as potential pharmaceutical targets. Surprisingly, several established risk loci, such as FLG, TSLP, and SPINK5, were not prioritized, and the gene list showed only marginal enrichment for skin- and barrier-related terms, despite confirming the intricate inflammatory mechanisms underlying eczema pathogenesis targeted in therapeutic interventions involving IL-4, IL-13, and JAK-STAT signaling pathways. The study also provided new insights into tissue type-specific molecular interactions caused by causal variants, shedding light on previously unexplored aspects of eczema etiology.

Interactions between the genetic background of AD with epigenetic modifications are limited, however, furnishing valuable perspectives in the etiology of eczema. Recent studies have identified hypermethylation of the VSTM1 promoter region in monocytes, encoding the negative inflammatory regulator SIRL-1. This methylation profile is dependent on the allelic status of the VSTM1 rs612529T/C SNP, with the C allele indicating increased methylation and, thus, repressed expression. Significant insights were further provided for the independent KIF3A rs11740584 and rs2299007 risk variants, promoting the formation of CpG islands. Specifically, the rs11740584G and rs2299007G alleles form novel CpG sites that lead to the hypermethylation and suppression of the KIF3A expression, a gene responsible for the skin barrier dysfunction in Kif3αK14Δ/Δ mice, indicating a causal role in eczema pathogenesis through their interaction with epigenetic modifications [44].

4. Immune Dysregulation in Atopic Dermatitis

The immune system’s interaction with the skin is crucial in AD pathogenesis. As the body’s primary defense, the skin relies on a coordinated immune response to protect against infections. However, this balance is disrupted in eczema, leading to dysregulated immune responses that trigger chronic inflammation and compromise the skin’s protective barrier. The abnormal immune response in AD contributes to the complex nature of the disease, highlighting the need to understand the intricate immunological mechanisms for effective treatments. AD is influenced by a combination of inflammatory and environmental factors, resulting in persistent inflammation and an imbalanced immune response, primarily characterized by type 2 inflammation.

Moreover, inborn errors of immunity, typically associated with increased susceptibility to infections, can also lead to immune dysregulation, including allergic inflammation. Recently, the term primary atopic disorders (PADs) have emerged to describe heritable monogenic allergic disorders. Clinicians should be aware that allergic conditions such as AD, food allergy, and asthma can be manifestations of misdirected immunity in patients with inborn errors of immunity. The presence of severe, early-onset, or coexisting allergic conditions may signal an underlying PAD, and its early recognition is crucial for informed treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes. Next-generation sequencing can aid in the identification of monogenic allergic diseases, enabling precise therapeutic interventions targeting specific molecular defects [45][46][47][48].

The extrinsic exposome, such as allergens and mechanical injury, can trigger the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-33, IL-25, IL-18, and chemokines such as CCL17 and CCL22, from skin cells in the stratum corneum and dendritic cells resident in the skin. These factors create a hostile inflammatory environment that promotes increased sensitization [49][50][51][52][53][54]. IL-33 stimulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) causes the production of IL-5, while the polarization of CD4+ naïve T cells to the predominant Th2 phenotype causes secretion of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which are the signature cytokines in AD. Therapeutic strategies target these cytokines as they play key roles in the pathogenesis of the disease [55][56][57]. The Th2-mediated cytokine cascade triggers molecular pathways with diverse mechanisms of action, including the pro-inflammatory JAK/STAT signaling pathway that affects immune cell differentiation and activation [58]. IL-13 is a key cytokine in the development of AD, with miR-143 shown to be capable of regulating its receptor, IL-13Rα1, and preventing the IL-13-mediated dysregulation of proteins such as Filaggrin (FLG), Loricrin (LOR), and Involucrin (IVL), which are essential for the integrity of the skin barrier [59].

In addition, miR-155-5p has been shown to alter the expression of various proteins, including protein kinase inhibitor α, tight junction proteins such as occludin and claudins, and TSLP, thereby regulating allergic inflammation [60][61][62]. An increase of the BIC gene, which encodes the miR-155 precursor, in the skin of AD patients compared to healthy controls, suggests that genetic variants in the miR-155 gene may play a role in AD susceptibility; three of the five SNPs spanning the BIC/miR-155 gene were associated with AD, however without statistical significance [63].

IL-13 binds to the IL-4Rα receptor, expressed on keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and immune cells, and is capable of inhibiting OVOL1 signaling as well as activating IL-24 production via periostin, with both pathways leading to suppression of FLG expression [64][65]. Notably, genes encoding the above molecules have all been identified as risk loci in the latest AD GWAS [6]. In contrast, IL-4 demonstrates its pathogenic role in AD by orchestrating the allergic response and is involved in the major histopathological features of AD through induction of immunoglobin E (IgE) production by B cells and suppression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) production in keratinocytes [66][67]. Recently IL-4Rα Q576R polymorphism was found to predispose to increased AD severity and aggravation of allergic skin inflammation in mice [68][69]. Furthermore, IgE secretion induces the degranulation of mast cells (MCs) and secretion of pro-inflammatory histamine, IL-31, and IL-6 [70][71][72], exacerbating itching and wounding and thus predisposing to microbial infections. The persistence of the described type 2 inflammation, which is supported by the co-regulatory contribution of additional signals such as Th1 and Th17 pathways, governs the progression of acute AD into a chronic inflammatory state [73][74][75].

5. Barrier Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis

Despite the significant contribution of immune dysregulation in the manifestation of AD, epidermal barrier dysfunction also holds a pivotal role. The skin barrier serves as a critical defense mechanism against extrinsic exposomes, including microbes, chemicals, and UV radiation. Comprising the stratum corneum, a layer of deceased keratinocytes and lipids, the skin barrier acts as a physical barrier to prevent the ingress of harmful substances. Additionally, it also plays a vital role in maintaining skin hydration by preventing water loss. However, in AD, there is a disturbance in the skin integrity, leading to increased water loss and increased susceptibility to irritants and allergens. This barrier dysfunction is considered a fundamental intrinsic disease factor involved in the development and progression of AD, and therefore unveiling the intricate interplay between immune dysregulation and barrier dysfunction is critical to elucidating the complex pathophysiology of AD.

The importance of the skin barrier in AD pathogenesis has been widely demonstrated through the consistent associations of FLG LOF variants with the disease predisposition. The dynamic process of keratinocyte (KC) migration from the basal cell layer towards the outermost layer of the skin, the stratum corneum, is accompanied by complex differentiation processes and the expression of distinct cellular markers [76]. Notably, the expression of filaggrin serves as an ideal marker during the final stages of keratinocyte differentiation, which occur in the granular and cornified layers. Proteolytic breakdown of pro-filaggrin into filaggrin monomers leads to the aggregation of keratin filaments, in conjunction with the expression of relevant structural proteins mapped to the EDC cluster (e.g., LOR, ILV, and SPRR proteins) [77]. These molecules are then crosslinked by transglutaminases (TGs), ultimately composing a scaffold-like structure to form the cornified envelope. At the uppermost layer of the skin, the keratin bundles foster the morphological transformation of KCs to form the corneocytes, flattened cells without intracellular organelles and nuclei [78]. Corneocytes are subsequently tightly interlinked with corneodesmosomes that are formed via the immobilization of desmosomes at the intercellular matrix mediated by TGs [79].

Filaggrin deficiency through LOF and structural variants significantly alters the structural composition of the cornified envelope, thus affecting the formation of corneocytes and enhancing the cutaneous sensitization to allergic factors [80][81][82][83]. Filaggrin deficiency can further exacerbate the inflammation and dysfunctional skin barrier through increasing pH, activating serine proteases (SPs) and kallikreins (KLKs) that participate in desquamation, a process that involves the constant replacement of corneocytes in the cornified envelope [84][85][86][87][88]. Variants mapped in both kallikrein-encoding genes (e.g., KLK7), as well as serine protease inhibitors (e.g., SPINK5), have been associated with eczema [89][90]. However, the implication of several exogenous factors, such as house dust mites (HDMs), allergens, and S. aureus infection with the exotoxins that induce type 2 inflammation through IgE and aggravate the epidermal barrier dysfunction, as well as the severe immunological background of the disease has established the inside-outside or outside-inside hypothesis debate in eczema pathogenesis, nevertheless suggested incorporating both factors and relevant molecular abnormalities [91][92].

In parallel, exposure to air pollutants induces oxidative stress in the skin, which has been demonstrated to compromise the integrity of the skin barrier by affecting transepidermal water loss (TEWL), initiating inflammatory responses, altering the pH of the stratum corneum, and impacting the skin microbiome [93][94]. Several oxidative stress markers in the stratum corneum of AD biopsies have exhibited a correlation with the severity of AD. The levels of carbonyl moieties, lipid peroxidation, and superoxide dismutase activity in skin biopsies of 75 patients with AD were evaluated and compared to diseased and normal controls. The findings revealed elevated levels of protein carbonyl moieties in AD, which were directly associated with the severity of the condition. Immunostaining with anti-DNP and anti-4-HNE antibodies indicated positive staining in the outermost layers of the stratum corneum, suggesting that environmental reactive oxygen species (ROS) might cause oxidation to proteins in the stratum corneum, and consequent barrier dysfunction and aggravation of AD [95].

6. Microbial Dysbiosis in Atopic Dermatitis

The profound diversity of microbial organisms that colonize the human body constitutes a captivating ecosystem, impacting human health and well-being through multifaceted interactions and mechanisms. In particular, the skin microbiome assumes a pivotal role in the host’s defense mechanisms, acting as an additional barrier against external pathogens, modulating immune responses, and contributing to the maintenance of cutaneous homeostasis [96]. Likewise, the gut microbiome participates in an abundance of physiological processes, such as metabolism, digestion, and immune responses, and has been implicated in systemic disorders; dysbiosis of microbial populations in both tissues can be perpetuated by aberrant immune responses, leading to a vicious cycle mediated by the inflammatory cascade [97][98]. In eczema, such interactions between the impaired skin barrier, perturbed immune response, and microbial alterations strongly participate in both the disease onset as well as the maintenance phase; nevertheless, molecular changes have yet to be systematically elucidated.

The perturbed microbial composition in patients with AD has been extensively characterized, with the presence of S. aureus governing the dysfunctional epithelial barrier along with the reduction of glycerol fermentation bacteria, such as C. acnes and S. epidermis [99][100]. Beheshti and colleagues conducted a comprehensive multi-omics assessment of saliva samples from 37 AD infants, employing targeted cytokine, human mRNA, miRNA, and 16s ribosomal RNA analyses to unveil putative novel pathological mechanisms in eczema onset [101]. Despite focusing on identified deregulated markers of AD, with the exemplars of FLG, SPINK5, mir-146b, and alpha diversity of Proteobacteria, significant differences were uncovered for several molecular factors, such as mir-375, mir-21, Th1/Th2 ratio (measured by the IL-8/IL-6 ratio) and Proteobacteria abundance, with the latter being positively correlated with the expression levels of mir-375 (rho = 0.21). Alpha diversity also reported a positive correlation with the AD severity, further emphasizing the prominent role of the microbiome in disease pathogenesis. Notably, statistically significant factors from each -omics analysis showed a high discriminative ability as measured by the receiver operator characteristics curve (c-statistic = 0.814), providing the framework for additional investigation of such factors in the cutaneous inflammation.

Despite the limited research on histone modification in the eczema landscape, Traisaeng and colleagues explored the potential therapeutic implication of butyric acid analogs in AD through the inhibition of S. aureus colonization and effects on histone modifications in HaCaT KCs [102]. Butyric acid, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), exhibits anti-microbial activity as well as represses the expression of histone deacetylase (HDAC), leading to increased transcriptional activity and has been proposed as a potent anti-inflammatory modulator [103][104]. The abundance of S. aureus in eczema skin was significantly reduced at in vitro co-culture with S. epidermis, accompanied by the presence of 2% glycerol through glycerol fermentation, as well as in AD mice suppressing the expression of IL-6. Administration of water-soluble butyric acid (BA–NH–NH–BA), the sole fermentation metabolite of S. epidermidis, in HaCaT KCs increased the levels of acetylated Histone H3 lysine 9 (AcH3K9), reporting as well dose-dependent reduction of cutaneous IL-6 levels. The investigation of histone modifications accompanied by the microbial diversity in eczema is of paramount importance to unveil the underlying molecular mechanisms and highlight possible therapeutic targets.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm12124000

References

- Nutten, S. Atopic Dermatitis: Global Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 8–16.

- Grafanaki, K.; Bania, A.; Kaliatsi, E.G.; Vryzaki, E.; Vasilopoulos, Y.; Georgiou, S. The Imprint of Exposome on the Development of Atopic Dermatitis across the Lifespan: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2180.

- Mastraftsi, S.; Vrioni, G.; Bakakis, M.; Nicolaidou, E.; Rigopoulos, D.; Stratigos, A.J.; Gregoriou, S. Atopic Dermatitis: Striving for Reliable Biomarkers. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4639.

- Facheris, P.; Da Rosa, J.C.; Pagan, A.D.; Angelov, M.; Del Duca, E.; Rabinowitz, G.; Gómez-Arias, P.J.; Rothenberg-Lausell, C.; Estrada, Y.D.; Bose, S.; et al. Age of Onset Defines Two Distinct Profiles of Atopic Dermatitis in Adults. Allergy 2023.

- Smieszek, S.P.; Welsh, S.; Xiao, C.; Wang, J.; Polymeropoulos, C.; Birznieks, G.; Polymeropoulos, M.H. Correlation of Age-of-Onset of Atopic Dermatitis with Filaggrin Loss-of-Function Variant Status. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2721.

- Ried, J.S.; Li, J.; Zuo, X.B.; Zheng, X.D.; Yin, X.Y.; Sun, L.D.; McAleer, M.A.; O’Regan, G.M.; Fahy, C.M.; Campbell, L.E. Multi-Ancestry Genome-Wide Association Study of 21,000 Cases and 95,000 Controls Identifies New Risk Loci for Atopic Dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1449–1456.

- Allis, C.D.; Jenuwein, T. The Molecular Hallmarks of Epigenetic Control. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 487–500.

- Li, J.; Liu, C. Coding or Noncoding, the Converging Concepts of RNAs. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 496.

- Kristensen, L.S.; Andersen, M.S.; Stagsted, L.V.W.; Ebbesen, K.K.; Hansen, T.B.; Kjems, J. The Biogenesis, Biology and Characterization of Circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 675–691.

- Moldovan, L.I.; Tsoi, L.C.; Ranjitha, U.; Hager, H.; Weidinger, S.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Kjems, J.; Kristensen, L.S. Characterization of Circular RNA Transcriptomes in Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis Reveals Disease-specific Expression Profiles. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 1187–1196.

- Yang, L.; Fu, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, C.; Xia, L.; Zhu, R.; Huang, S.; Xiao, W.; Yu, H.; Gao, Y.; et al. Hsa_circ_0004287 Inhibits Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation in an N6-Methyladenosine–Dependent Manner in Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 2021–2033.

- Lv, Y.; Qi, R.; Xu, J.; Di, Z.; Zheng, H.; Huo, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Gao, X. Profiling of Serum and Urinary MicroRNAs in Children with Atopic Dermatitis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115448.

- Jia, H.-Z.; Liu, S.-L.; Zou, Y.-F.; Chen, X.-F.; Yu, L.; Wan, J.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Chen, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Yu, B.; et al. MicroRNA-223 Is Involved in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis by Affecting Histamine-N-Methyltransferase. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 64, 103–107.

- Yasuike, R.; Tamagawa-Mineoka, R.; Nakamura, N.; Masuda, K.; Katoh, N. Plasma MiR223 Is a Possible Biomarker for Diagnosing Patients with Severe Atopic Dermatitis. Allergol. Int. 2021, 70, 153–155.

- Taïbi, F.; Metzinger-Le Meuth, V.; Massy, Z.A.; Metzinger, L. MiR-223: An Inflammatory OncomiR Enters the Cardiovascular Field. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Basis Dis. 2014, 1842, 1001–1009.

- Béres, N.J.; Szabó, D.; Kocsis, D.; Szűcs, D.; Kiss, Z.; Müller, K.E.; Lendvai, G.; Kiss, A.; Arató, A.; Sziksz, E.; et al. Role of Altered Expression of MiR-146a, MiR-155, and MiR-122 in Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 327–335.

- Timis, T.; Orasan, R. Understanding Psoriasis: Role of MiRNAs (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2018, 9, 367–374.

- Ma, L.; Xue, H.-B.; Wang, F.; Shu, C.-M.; Zhang, J.-H. MicroRNA-155 May Be Involved in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis by Modulating the Differentiation and Function of T Helper Type 17 (Th17) Cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2015, 181, 142–149.

- Yan, F.; Meng, W.; Ye, S.; Zhang, X.; Mo, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, D.; Lin, Y. MicroRNA-146a as a Potential Regulator Involved in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 4645–4653.

- Ueta, M.; Nishigaki, H.; Komai, S.; Mizushima, K.; Tamagawa-Mineoka, R.; Naito, Y.; Katoh, N.; Sotozono, C.; Kinoshita, S. Positive Regulation of Innate Immune Response by MiRNA-Let-7a-5p. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1025539.

- Nousbeck, J.; McAleer, M.A.; Hurault, G.; Kenny, E.; Harte, K.; Kezic, S.; Tanaka, R.J.; Irvine, A.D. MicroRNA Analysis of Childhood Atopic Dermatitis Reveals a Role for MiR-451a. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 514–523.

- Chen, X.-F.; Zhang, L.-J.; Zhang, J.; Dou, X.; Shao, Y.; Jia, X.-J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, B. MiR-151a Is Involved in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis by Regulating Interleukin-12 Receptor Β2. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 427–432.

- Li, B.; Xia, Y.; Lv, J.; Wang, W.; Xuan, Z.; Chen, C.; Jiang, T.; Fang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; et al. MiR-151a-3p-Rich Small Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Gastric Cancer Accelerate Liver Metastasis via Initiating a Hepatic Stemness-Enhancing Niche. Oncogene 2021, 40, 6180–6194.

- Daugaard, I.; Sanders, K.J.; Idica, A.; Vittayarukskul, K.; Hamdorf, M.; Krog, J.D.; Chow, R.; Jury, D.; Hansen, L.L.; Hager, H.; et al. MiR-151a Induces Partial EMT by Regulating E-Cadherin in NSCLC Cells. Oncogenesis 2017, 6, e366.

- Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Sun, P.; Xiang, R.; Yang, S. Exosomal MiR-451a Functions as a Tumor Suppressor in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Targeting LPIN1. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 53, 19–35.

- Bai, H.; Wu, S. MiR-451: A Novel Biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target for Cancer. Onco. Targets. Ther. 2019, 12, 11069–11082.

- Meng, L.; Li, M.; Gao, Z.; Ren, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Cai, Q.; Jiang, L.; Ren, X.; Yu, Q.; et al. Possible Role of Hsa-MiR-194-5p, via Regulation of HS3ST2, in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis in Children. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2019, 29, 603–613.

- Yen, Y.-T.; Yang, J.-C.; Chang, J.-B.; Tsai, S.-C. Down-Regulation of MiR-194-5p for Predicting Metastasis in Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 325.

- Rebane, A.; Runnel, T.; Aab, A.; Maslovskaja, J.; Rückert, B.; Zimmermann, M.; Plaas, M.; Kärner, J.; Treis, A.; Pihlap, M.; et al. MicroRNA-146a Alleviates Chronic Skin Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis through Suppression of Innate Immune Responses in Keratinocytes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 836–847.e11.

- Carreras-Badosa, G.; Maslovskaja, J.; Vaher, H.; Pajusaar, L.; Annilo, T.; Lättekivi, F.; Hübenthal, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Weidinger, S.; Kingo, K.; et al. MiRNA Expression Profiles of the Perilesional Skin of Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis Patients Are Highly Similar. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22645.

- Vennegaard, M.T.; Bonefeld, C.M.; Hagedorn, P.H.; Bangsgaard, N.; Løvendorf, M.B.; Ødum, N.; Woetmann, A.; Geisler, C.; Skov, L. Allergic Contact Dermatitis Induces Upregulation of Identical MicroRNAs in Humans and Mice. Contact Dermat. 2012, 67, 298–305.

- Chang, J.; Zhou, B.; Wei, Z.; Luo, Y. IL-32 Promotes the Occurrence of Atopic Dermatitis by Activating the JAK1/MicroRNA-155 Axis. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 207.

- Sonkoly, E.; Janson, P.; Majuri, M.-L.; Savinko, T.; Fyhrquist, N.; Eidsmo, L.; Xu, N.; Meisgen, F.; Wei, T.; Bradley, M.; et al. MiR-155 Is Overexpressed in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis and Modulates T-Cell Proliferative Responses by Targeting Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte–Associated Antigen 4. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 581–589.e20.

- Zhong, Y.; Qin, K.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; Xie, Z.; Zeng, K. Identification of Immunological Biomarkers of Atopic Dermatitis by Integrated Analysis to Determine Molecular Targets for Diagnosis and Therapy. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 8193–8209.

- Peng, S.; Chen, M.; Yin, M.; Feng, H. Identifying the Potential Therapeutic Targets for Atopic Dermatitis Through the Immune Infiltration Analysis and Construction of a CeRNA Network. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 14, 437–453.

- Li, H.M.; Xiao, Y.J.; Min, Z.S.; Tan, C. Identification and Interaction Analysis of Key Genes and MicroRNAs in Atopic Dermatitis by Bioinformatics Analysis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 44, 257–264.

- Acharjee, A.; Gribaleva, E.; Bano, S.; Gkoutos, G.V. Multi-Omics-Based Identification of Atopic Dermatitis Target Genes and Their Potential Associations with Metabolites and MiRNAs. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 13697–13709.

- Yang, Z.; Zeng, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, P.; Pan, Y. MicroRNA-124 Alleviates Chronic Skin Inflammation in Atopic Eczema via Suppressing Innate Immune Responses in Keratinocytes. Cell Immunol. 2017, 319, 53–60.

- Yan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, C.; Qian, Q.; Mao, J.; Sun, D.; Zhu, T. MiR-1294 Suppresses ROS-Dependent Inflammatory Response in Atopic Dermatitis via Restraining STAT3/NF-ΚB Pathway. Cell Immunol. 2022, 371, 104452.

- Chen, K.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Z. MiR-1294 Inhibits the Progression of Breast Cancer via Regulating ERK Signaling. Bull. Cancer 2022, 109, 999–1006.

- Yang, S.-C.; Alalaiwe, A.; Lin, Z.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Aljuffali, I.A.; Fang, J.-Y. Anti-Inflammatory MicroRNAs for Treating Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1072.

- Nica, A.C.; Dermitzakis, E.T. Expression Quantitative Trait Loci: Present and Future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120362.

- Sobczyk, M.K.; Richardson, T.G.; Zuber, V.; Min, J.L.; Gaunt, T.R.; Paternoster, L. Triangulating Molecular Evidence to Prioritize Candidate Causal Genes at Established Atopic Dermatitis Loci. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 2620–2629.

- Kumar, D.; Puan, K.J.; Andiappan, A.K.; Lee, B.; Westerlaken, G.H.A.; Haase, D.; Melchiotti, R.; Li, Z.; Yusof, N.; Lum, J.; et al. A Functional SNP Associated with Atopic Dermatitis Controls Cell Type-Specific Methylation of the VSTM1 Gene Locus. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 18.

- Lyons, J.J.; Milner, J.D. Primary Atopic Disorders. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 1009–1022.

- Vaseghi-Shanjani, M.; Smith, K.L.; Sara, R.J.; Modi, B.P.; Branch, A.; Sharma, M.; Lu, H.Y.; James, E.L.; Hildebrand, K.J.; Biggs, C.M.; et al. Inborn Errors of Immunity Manifesting as Atopic Disorders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 1130–1139.

- Turvey, S.E.; Bonilla, F.A.; Junker, A.K. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. Postgrad. Med. J. 2009, 85, 660–666.

- Del Bel, K.L.; Ragotte, R.J.; Saferali, A.; Lee, S.; Vercauteren, S.M.; Mostafavi, S.A.; Schreiber, R.A.; Prendiville, J.S.; Phang, M.S.; Halparin, J.; et al. JAK1 Gain-of-Function Causes an Autosomal Dominant Immune Dysregulatory and Hypereosinophilic Syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 2016–2020.e5.

- Oyoshi, M.K.; Larson, R.P.; Ziegler, S.F.; Geha, R.S. Mechanical Injury Polarizes Skin Dendritic Cells to Elicit a TH2 Response by Inducing Cutaneous Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin Expression. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 976–984.e5.

- Cevikbas, F.; Steinhoff, M. IL-33: A Novel Danger Signal System in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 1326–1329.

- Hvid, M.; Vestergaard, C.; Kemp, K.; Christensen, G.B.; Deleuran, B.; Deleuran, M. IL-25 in Atopic Dermatitis: A Possible Link between Inflammation and Skin Barrier Dysfunction? J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 150–157.

- Konishi, H.; Tsutsui, H.; Murakami, T.; Yumikura-Futatsugi, S.; Yamanaka, K.; Tanaka, M.; Iwakura, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; et al. IL-18 Contributes to the Spontaneous Development of Atopic Dermatitis-like Inflammatory Skin Lesion Independently of IgE/Stat6 under Specific Pathogen-Free Conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11340–11345.

- Halling, A.-S.; Rinnov, M.R.; Ruge, I.F.; Gerner, T.; Ravn, N.H.; Knudgaard, M.H.; Trautner, S.; Loft, N.; Skov, L.; Thomsen, S.F.; et al. Skin TARC/CCL17 Increase Precedes the Development of Childhood Atopic Dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 151, 1550–1557.e6.

- Hulshof, L.; Overbeek, S.A.; Wyllie, A.L.; Chu, M.L.J.N.; Bogaert, D.; de Jager, W.; Knippels, L.M.J.; Sanders, E.A.M.; van Aalderen, W.M.C.; Garssen, J.; et al. Exploring Immune Development in Infants with Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 630.

- Klonowska, J.; Gleń, J.; Nowicki, R.; Trzeciak, M. New Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis—New Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3086.

- Neis, M.; Peters, B.; Dreuw, A.; Wenzel, J.; Bieber, T.; Mauch, C.; Krieg, T.; Stanzel, S.; Heinrich, P.; Merk, H. Enhanced Expression Levels of IL-31 Correlate with IL-4 and IL-13 in Atopic and Allergic Contact Dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 930–937.

- Kamata, M.; Tada, Y. A Literature Review of Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Dupilumab for Atopic Dermatitis. JID Innov. 2021, 1, 100042.

- Bao, L.; Zhang, H.; Chan, L.S. The Involvement of the JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway in Chronic Inflammatory Skin Disease Atopic Dermatitis. JAK-STAT 2013, 2, e24137.

- Tsoi, L.C.; Rodriguez, E.; Degenhardt, F.; Baurecht, H.; Wehkamp, U.; Volks, N.; Szymczak, S.; Swindell, W.R.; Sarkar, M.K.; Raja, K.; et al. Atopic Dermatitis Is an IL-13–Dominant Disease with Greater Molecular Heterogeneity Compared to Psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 1480–1489.

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, W.; Yao, L.; Wang, S.; Jia, Z.; Wu, P.; Li, L.; Wei, P.; Wang, X.; et al. MicroRNA-155-5p Is a Key Regulator of Allergic Inflammation, Modulating the Epithelial Barrier by Targeting PKIα. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 884.

- Zeng, Y.-P.; Nguyen, G.H.; Jin, H.-Z. MicroRNA-143 Inhibits IL-13-Induced Dysregulation of the Epidermal Barrier-Related Proteins in Skin Keratinocytes via Targeting to IL-13Rα1. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2016, 416, 63–70.

- Li, X.; Ponandai-Srinivasan, S.; Nandakumar, K.S.; Fabre, S.; Xu Landén, N.; Mavon, A.; Khmaladze, I. Targeting microRNA for Improved Skin Health. Health Sci. Rep. 2021, 4, e374.

- Sääf, A.; Kockum, I.; Wahlgren, C.; Xu, N.; Sonkoly, E.; Ståhle, M.; Nordenskjöld, M.; Bradley, M.; Pivarcsi, A. Are BIC (MiR-155) Polymorphisms Associated with Eczema Susceptibility? Acta Derm. Venereol. 2013, 93, 366–367.

- Tsuji, G.; Ito, T.; Chiba, T.; Mitoma, C.; Nakahara, T.; Uchi, H.; Furue, M. The Role of the OVOL1–OVOL2 Axis in Normal and Diseased Human Skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2018, 90, 227–231.

- Mitamura, Y.; Nunomura, S.; Nanri, Y.; Ogawa, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Masuoka, M.; Tsuji, G.; Nakahara, T.; Hashimoto-Hachiya, A.; Conway, S.J.; et al. The IL-13/Periostin/IL-24 Pathway Causes Epidermal Barrier Dysfunction in Allergic Skin Inflammation. Allergy 2018, 73, 1881–1891.

- Lee, G.R. Transgenic Mice Which Overproduce Th2 Cytokines Develop Spontaneous Atopic Dermatitis and Asthma. Int. Immunol. 2004, 16, 1155–1160.

- Nomura, I.; Goleva, E.; Howell, M.D.; Hamid, Q.A.; Ong, P.Y.; Hall, C.F.; Darst, M.A.; Gao, B.; Boguniewicz, M.; Travers, J.B.; et al. Cytokine Milieu of Atopic Dermatitis, as Compared to Psoriasis, Skin Prevents Induction of Innate Immune Response Genes. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 3262–3269.

- Yang, B.; Wilkie, H.; Das, M.; Timilshina, M.; Bainter, W.; Woods, B.; Daya, M.; Boorgula, M.P.; Mathias, R.A.; Lai, P.; et al. The IL-4Rα Q576R Polymorphism Is Associated with Increased Severity of Atopic Dermatitis and Exaggerates Allergic Skin Inflammation in Mice. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 1296–1306.e7.

- DeBord, D.G.; Carreón, T.; Lentz, T.J.; Middendorf, P.J.; Hoover, M.D.; Schulte, P.A. Use of the “Exposome” in the Practice of Epidemiology: A Primer on -Omic Technologies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 184, 302–314.

- Conti, P.; Kempuraj, D.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Boucher, W.; Letourneau, R.; Kandere, K.; Barbacane, R.C.; Reale, M.; Felaco, M.; Frydas, S.; et al. Interleukin-6 and Mast Cells. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2002, 23, 331–335.

- Niyonsaba, F.; Ushio, H.; Hara, M.; Yokoi, H.; Tominaga, M.; Takamori, K.; Kajiwara, N.; Saito, H.; Nagaoka, I.; Ogawa, H.; et al. Antimicrobial Peptides Human β-Defensins and Cathelicidin LL-37 Induce the Secretion of a Pruritogenic Cytokine IL-31 by Human Mast Cells. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 3526–3534.

- Koumaki, D.; Gregoriou, S.; Evangelou, G.; Krasagakis, K. Pruritogenic Mediators and New Antipruritic Drugs in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2091.

- Novak, N.; Peng, W.M.; Bieber, T.; Akdis, C. FcεRI Stimulation Promotes the Differentiation of Histamine Receptor 1-Expressing Inflammatory Macrophages. Allergy 2013, 68, 454–461.

- Miake, S.; Tsuji, G.; Takemura, M.; Hashimoto-Hachiya, A.; Vu, Y.H.; Furue, M.; Nakahara, T. IL-4 Augments IL-31/IL-31 Receptor Alpha Interaction Leading to Enhanced Ccl 17 and Ccl 22 Production in Dendritic Cells: Implications for Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4053.

- Fujita, H.; Shemer, A.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Johnson-Huang, L.M.; Tintle, S.; Cardinale, I.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Novitskaya, I.; Carucci, J.A.; Krueger, J.G.; et al. Lesional Dendritic Cells in Patients with Chronic Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis Exhibit Parallel Ability to Activate T-Cell Subsets. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 574–582.e12.

- Candi, E.; Schmidt, R.; Melino, G. The Cornified Envelope: A Model of Cell Death in the Skin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 328–340.

- Oh, I.Y.; Albea, D.M.; Goodwin, Z.A.; Quiggle, A.M.; Baker, B.P.; Guggisberg, A.M.; Geahlen, J.H.; Kroner, G.M.; de Guzman Strong, C. Regulation of the Dynamic Chromatin Architecture of the Epidermal Differentiation Complex Is Mediated by a C-Jun/AP-1-Modulated Enhancer. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 2371–2380.

- Cork, M.J.; Robinson, D.A.; Vasilopoulos, Y.; Ferguson, A.; Moustafa, M.; MacGowan, A.; Duff, G.W.; Ward, S.J.; Tazi-Ahnini, R. New Perspectives on Epidermal Barrier Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis: Gene–Environment Interactions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 3–21.

- Hitomi, K. Transglutaminases in Skin Epidermis. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2005, 15, 313–319.

- Rodríguez, E.; Baurecht, H.; Herberich, E.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Brown, S.J.; Cordell, H.J.; Irvine, A.D.; Weidinger, S. Meta-Analysis of Filaggrin Polymorphisms in Eczema and Asthma: Robust Risk Factors in Atopic Disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, 1361–1370.e7.

- Margolis, D.J.; Mitra, N.; Berna, R.; Hoffstad, O.; Kim, B.S.; Yan, A.; Zaenglein, A.L.; Fuxench, Z.C.; Quiggle, A.M.; de Guzman Strong, C.; et al. Associating Filaggrin Copy Number Variation and Atopic Dermatitis in African-Americans: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2020, 98, 58–60.

- Brown, S.J.; Kroboth, K.; Sandilands, A.; Campbell, L.E.; Pohler, E.; Kezic, S.; Cordell, H.J.; McLean, W.H.I.; Irvine, A.D. Intragenic Copy Number Variation within Filaggrin Contributes to the Risk of Atopic Dermatitis with a Dose-Dependent Effect. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 98–104.

- Thyssen, J.P.; Kezic, S. Causes of Epidermal Filaggrin Reduction and Their Role in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 792–799.

- Hachem, J.-P.; Wagberg, F.; Schmuth, M.; Crumrine, D.; Lissens, W.; Jayakumar, A.; Houben, E.; Mauro, T.M.; Leonardsson, G.; Brattsand, M.; et al. Serine Protease Activity and Residual LEKTI Expression Determine Phenotype in Netherton Syndrome. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 1609–1621.

- Komatsu, N.; Saijoh, K.; Jayakumar, A.; Clayman, G.L.; Tohyama, M.; Suga, Y.; Mizuno, Y.; Tsukamoto, K.; Taniuchi, K.; Takehara, K.; et al. Correlation between SPINK5 Gene Mutations and Clinical Manifestations in Netherton Syndrome Patients. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 1148–1159.

- Komatsu, N.; Saijoh, K.; Kuk, C.; Liu, A.C.; Khan, S.; Shirasaki, F.; Takehara, K.; Diamandis, E.P. Human Tissue Kallikrein Expression in the Stratum Corneum and Serum of Atopic Dermatitis Patients. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 16, 513–519.

- Voegeli, R.; Rawlings, A.V.; Breternitz, M.; Doppler, S.; Schreier, T.; Fluhr, J.W. Increased Stratum Corneum Serine Protease Activity in Acute Eczematous Atopic Skin. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009, 161, 70–77.

- Has, C. Peeling Skin Disorders: A Paradigm for Skin Desquamation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1689–1691.

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Guo, X.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, H. Genetic Polymorphisms in Serine Protease Inhibitor Kazal-Type 5 and Risk of Atopic Dermatitis. Medicine 2020, 99, e21256.

- Weidinger, S.; Baurecht, H.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Henderson, J.; Novak, N.; Sandilands, A.; Chen, H.; Rodriguez, E.; O’Regan, G.M.; Watson, R.; et al. Analysis of the Individual and Aggregate Genetic Contributions of Previously Identified Serine Peptidase Inhibitor Kazal Type 5 (SPINK5), Kallikrein-Related Peptidase 7 (KLK7), and Filaggrin (FLG) Polymorphisms to Eczema Risk. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 122, 560–568.e4.

- Yoshida, T.; Beck, L.A.; De Benedetto, A. Skin Barrier Defects in Atopic Dermatitis: From Old Idea to New Opportunity. Allergol. Int. 2022, 71, 3–13.

- Meyer-Hoffert, U. Reddish, Scaly, and Itchy: How Proteases and Their Inhibitors Contribute to Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2009, 57, 345–354.

- Just, A.C.; Whyatt, R.M.; Perzanowski, M.S.; Calafat, A.M.; Perera, F.P.; Goldstein, I.F.; Chen, Q.; Rundle, A.G.; Miller, R.L. Prenatal Exposure to Butylbenzyl Phthalate and Early Eczema in an Urban Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1475–1480.

- Kathuria, P.; Silverberg, J.I. Association of Pollution and Climate with Atopic Eczema in US Children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27, 478–485.

- Niwa, Y.; Sumi, H.; Kawahira, K.; Terashima, T.; Nakamura, T.; Akamatsu, H. Protein Oxidative Damage in the Stratum Corneum: Evidence for a Link between Environmental Oxidants and the Changing Prevalence and Nature of Atopic Dermatitis in Japan. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 149, 248–254.

- Boxberger, M.; Cenizo, V.; Cassir, N.; La Scola, B. Challenges in Exploring and Manipulating the Human Skin Microbiome. Microbiome 2021, 9, 125.

- Mousa, W.K.; Chehadeh, F.; Husband, S. Microbial Dysbiosis in the Gut Drives Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 5936.

- van der Meulen, T.; Harmsen, H.; Bootsma, H.; Spijkervet, F.; Kroese, F.; Vissink, A. The Microbiome-Systemic Diseases Connection. Oral Dis. 2016, 22, 719–734.

- Kim, J.; Kim, H. Microbiome of the Skin and Gut in Atopic Dermatitis (AD): Understanding the Pathophysiology and Finding Novel Management Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 444.

- Alam, M.J.; Xie, L.; Yap, Y.-A.; Marques, F.Z.; Robert, R. Manipulating Microbiota to Treat Atopic Dermatitis: Functions and Therapies. Pathogens 2022, 11, 642.

- Beheshti, R.; Halstead, S.; McKeone, D.; Hicks, S.D. Understanding Immunological Origins of Atopic Dermatitis through Multi-omic Analysis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33, e13817.

- Traisaeng, S.; Herr, D.R.; Kao, H.-J.; Chuang, T.-H.; Huang, C.-M. A Derivative of Butyric Acid, the Fermentation Metabolite of Staphylococcus Epidermidis, Inhibits the Growth of a Staphylococcus aureus Strain Isolated from Atopic Dermatitis Patients. Toxins 2019, 11, 311.

- Lamas, A.; Regal, P.; Vázquez, B.; Cepeda, A.; Franco, C.M. Short Chain Fatty Acids Commonly Produced by Gut Microbiota Influence Salmonella enterica Motility, Biofilm Formation, and Gene Expression. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 265.

- Chriett, S.; Dąbek, A.; Wojtala, M.; Vidal, H.; Balcerczyk, A.; Pirola, L. Prominent Action of Butyrate over β-Hydroxybutyrate as Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, Transcriptional Modulator and Anti-Inflammatory Molecule. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 742.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!