Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) are incurable and debilitating conditions that result in progressive degeneration and/or death of nerve cells in the central nervous system (CNS). High-throughput screening (HTS) has increasingly been used for novel drug discovery in the field of pharmaceutics replacing the traditional “trial and error” approach to identify therapeutic targets and validate biological effects. HTS involves assaying and screening a large number of biological effectors and modulators against designated and exclusive targets.

- high-throughput screening

- HTS

- neurodegenerative diseases

- drug discovery

1. Formats and Major Considerations for HTS Platforms

HTS involves in vitro, cell- or whole organism- based assays [1]. The most common readouts for biochemical assays in HTS are optical, including absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, and scintillation. The efficiency of data production and cost per screen are the main determinants in the choice of the most suitable readout for a particular screen. However, the fluorescence-based techniques are considered as one of the primary detection methods [2]. This can mainly be attributed to the high sensitivity and diverse range of available fluorophores enabling multiplexed readouts which allow miniaturization, assay design stability, ease of handling, and the ability to simultaneously track several events in real time [3]. However, it is important to note that short wavelength excitation (particularly those under 400 nm) should be avoided during the development of functional assays in order to reduce interference from test compounds [4][5][6]. This direct screening approach has been applied to the selection of thrombin inhibitors, HIV-protease inhibitors, DNA gyrase inhibitors, etc. [7][8][9]. Quantitative kinetics of compound binding can be used to gain a higher level of understanding of binding mechanisms, as it is possible to investigate the effect of structural variations in a systematic way. Association and dissociation rates can vary independently for a specific lead series, resulting in the rapid evolution of sub nanomolar-affinity leads [10].

Data from screens can be archived and reviewed using information management systems [11] or more laboriously, in Excel spreadsheets. The data is evaluated in order to classify hits: Data points that surpass a certain specified threshold to determine a positive result. Importantly, the threshold limits can be quite subjective, but a value of three standard deviations from the mean signal of wells treated with DMSO, for example, is a fair and typical cut-off, since it offers a manageable false-positive statistical hit rate (0.15%) [12]. Alternatively, the maximum number of hits that can be processed may be increased by “cherry picking”, normally several hundred compounds can be simply picked for further evaluation. Additionally, the median rather than the mean for a single compound can be used to assess hits if the screening is done in triplicate together with the use of appropriate statistical methods [12]. This protects against the undue influence of significant outlier results, which are common in these techniques.

2. Main Types of HTS Assays

2.1. Cell-Based Assays

Using cell-based assays, whole pathways can be investigated generating numerous potential points of interest, as opposed to the analysis of particular predetermined steps as in biochemical assays. Moreover, cell-based assays may provide data that cannot be obtained from a biochemical assay, such as the existence of the pharmacological activity of the screened compound at a particular receptor or the intracellular target [13][14]. Consequently, cell-based platforms are especially promising as important tools in the study of cell growth and differentiation, in examining the influence of small molecules and cell growth conditions on cell function and physiology, and also in understanding signaling pathways in mammalian cells. They have also proven to be particularly valuable in studying complex conditions such as CNS injury and NDDs, as many factors can contribute to a specific cellular response [15].

HTS is frequently accomplished using scaled down cell-based methods. Cell-based tests enable chemical libraries to be tested for molecules that exhibit a diversity of biological activities. In the pharmaceutical industry, cellular microarrays utilizing 96- or 384-well microtiter plates with 2D cell monolayer cultures are commonly used [15]. Cellular microarrays consist of a solid framework wherein minute volumes of diverse biomolecules and cells can be presented, permitting the multiplexed examination of living cells and, subsequently, the assessment of cellular reactions [13][16]. Miscellaneous molecules such as antibodies, polymers and small molecules can be arrayed using automated spotting technology or soft lithography [17]. Cellular microarrays are also used in small molecule screening [18][19]. The screening of small molecules in mammalian cell lines, such as CHO cells, could be considered as an example of utilization of such a system [20][21]. There is flexibility in choosing the readout when using a cell-based assay focused on a signaling pathway. For example, if an antibody is available, every stage in which a protein is modified (e.g., phosphorylated), translocated [22] or changed in its abundance [23][24][25] can be possible readouts [26]. Multiple NDDs have been studied both with target-based and cell-based screens, including AD [27], PD [28], bipolar disease, autism and schizophrenia [29]. A key feature of cell-based screening is that multiple targets are screened at once, the readout being the outcome of a cellular pathway or network [30].

2.2. Biochemical Assays

Biochemical screening utilizes a purified target protein of interest and measures the binding of ligands or the inhibition of enzymatic activity in vitro [31]. These assays are generally conducted in a competition format, in which the compound under study displaces a known ligand or substrate. These assays are typically conducted in 384-well plates, which provide a good compromise between screening volumes (20–50 µL), throughput, and the cost of more sophisticated screening equipment. The readout is typically an optical method such as absorbance, fluorescence or luminescence [32]. Buratti et al. developed a method in which the activity of a specific RNA binding protein (RBP) (TDP-43) was measured, and due to the established activity of this protein, RBP was shown to be involved in the pathology of PD, AD, and other NDDs [33]. Additionally, Crowe et al. performed a novel study, screening almost 300,000 compounds to evaluate their effect on tau protein assembly. Formation of toxic tau oligomers in the brain is one of the main observed pathologic events of AD [34]. Using HTS assays based on complementary thioflavin T fluorescence and fluorescence polarization methods, the effects of inhibitors of tau oligomerization were determined. Specifically, that aminothienopyridazines (ATPZs) caused the inhibition of fibril assembly as well as fibrillization of tau. Additionally, the normal ability of tau to stabilize microtubules was not affected and ATPZs were shown to be promising drugs to treat AD [34][35]. Scaling down of bioanalytical activities, in order to decrease production expenses, as well as simplifying transport and saving space in the laboratory has led to a focus on laboratory-on-a-chip technology. Overall, scaling down improves the efficiency of required screening [36][37]. However, this could be complicated by extensive time implications, error-recovery rates, and complex experimental design often involving an error-prone robotic operation.

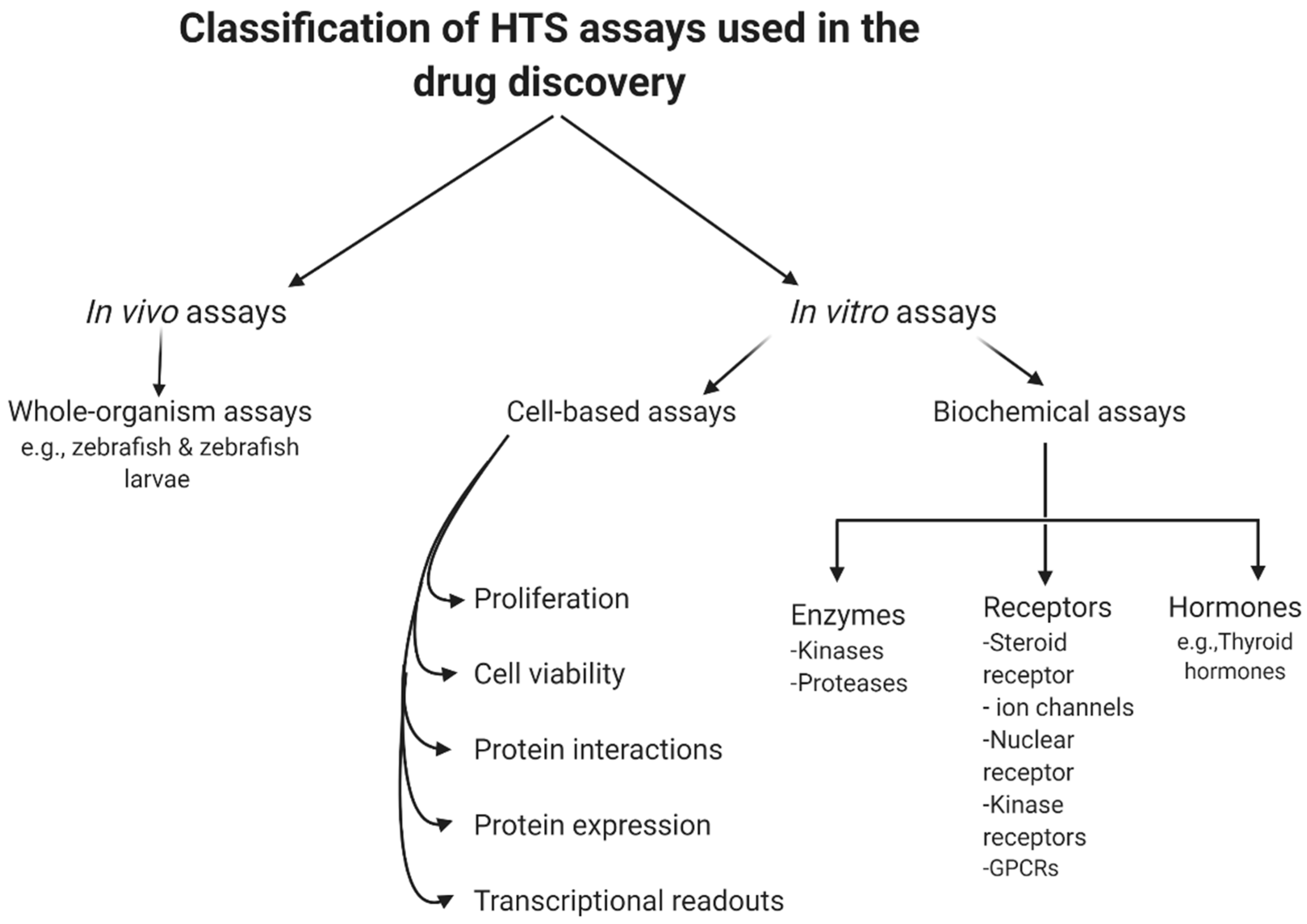

In summary, biochemical assays have the advantage that all hits found are against a known target by design. However, in those situations, the often costly and tedious determination of the molecular mechanisms of action would be needed, even though the target is known. Furthermore, due to the degree to which the predicted target was initially validated in the disease phase, the therapeutic potential of an in vitro hit can still be inconsistent. Even following the determination of such mechanistic details, it is difficult to predict the behavior of such compounds in a more complex cellular environment, due to variability in cellular permeability and metabolism, toxicity, selectivity, and the potential off-target activity of the compound [38]. However, cell-based assays have the benefit of detecting compounds that affect a phenotype in a complex cellular environment, but still suffer from a poor understanding of the target and mechanism of action. In addition, these experiments are usually more expensive and difficult to conform to miniature HTS assays [39]. Figure 1 summarizes the current classification of the main HTS assays.

Figure 1. General classification of high-throughput screening (HTS) assays.

3. Economics of HTS

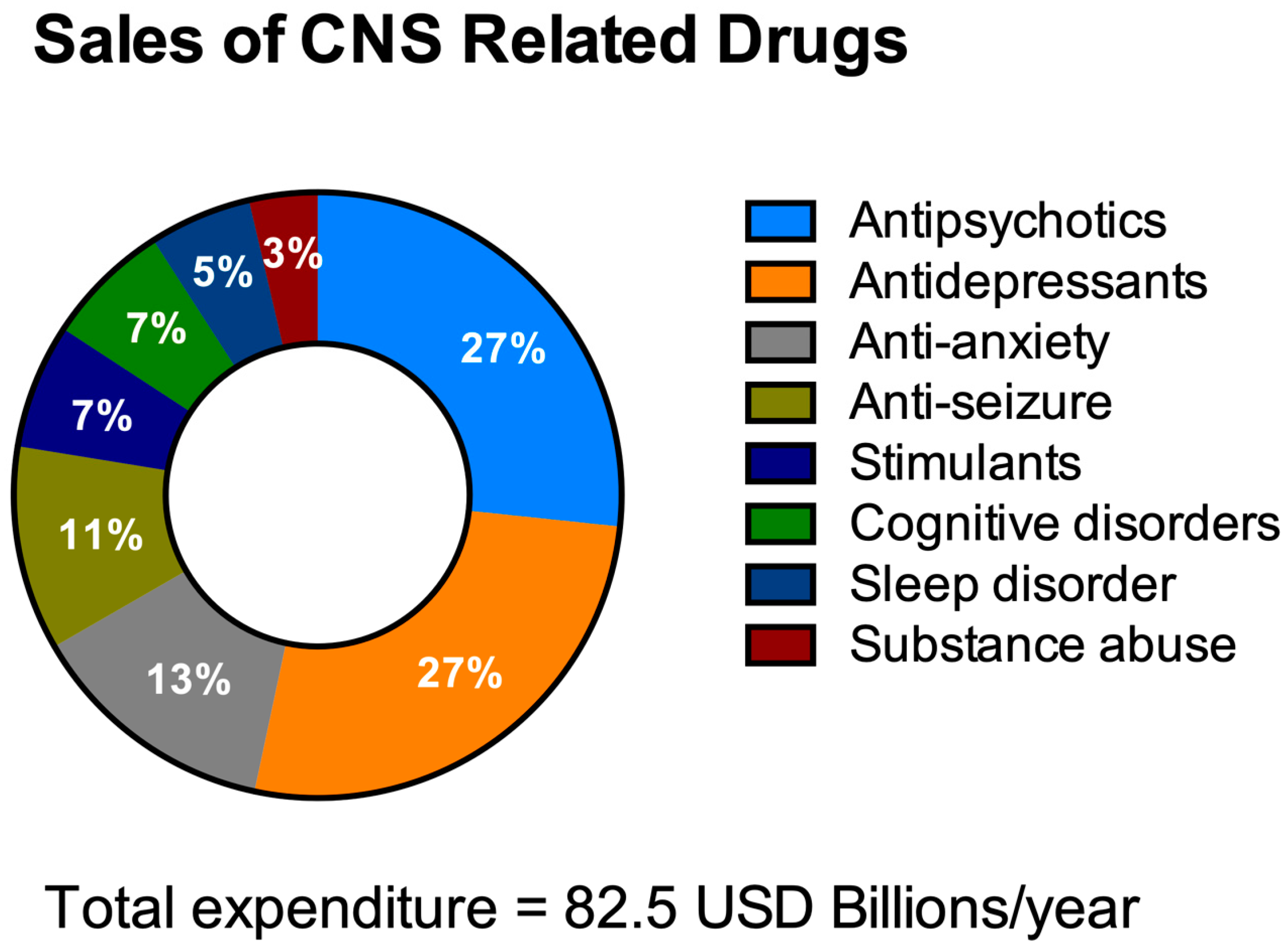

HTS aims to decrease the costs of drug invention [40][41]. It is necessary to address the economics of HTS for NDDs drug discovery especially with the escalating yearly costs of mental and neurological pathologies (estimated to be around USD 1 trillion [42]) including drug sales figures (Figure 2). It is remarkable to note that 40% of these total costs were attributable to the lack of productivity of the affected population due to the presence of these diseases [43]. The financial burden of these pathologies is only likely to increase as they typically have long-term consequences combined with an increasingly aging population.

Figure 2. Total expenditure on central nervous system (CNS)-related drugs in 2010. Adapted from Gustavsson et al., 2011 [44].

The primary explanation for this under-development of the worldwide brain drug market is that the vast majority of CNS drugs do not cross the in vivo blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB is a unique and highly selective vascular interface that separates the peripheral blood circulation from the neural tissue in order to maintain an optimum homeostatic microenvironment for brain function and protection [45][46]. However, biology’s proverbial double-edged sword means that the protective nature of the BBB precludes almost all large-molecule neurotherapeutics and more than 98% of all small-molecules as viable drugs [47]. In one systematic medicinal research study, over 7000 drugs were evaluated in the comprehensive medicinal chemistry (CMC) database [48] and this suggested that the CNS was affected by just 5% of these medications. In another study, only one out of every eight medicines analyzed were active in the CNS and only 1% of the total number of drugs were clinically active in the CNS for diseases [49].

The procedure involved in developing a new drug is an elaborative effort which is often a costly and lengthy process. On average, the cost of developing a new medicine is around USD 1.3 billion (2018) [50]. However, the expenditure of the research and development (R&D) departments of the major pharmaceutical companies can be as high as USD 2.87 billion (2013) to discover and test a new drug [51]. Despite these huge investments in new treatments targeting NNDs and an expanding pipeline, there have been more failures and setbacks than overall treatment successes. The failure rate of clinical trials for new treatments targeting NDDs, for example AD, is exceptionally high and usually exceeds 99% [52]. For example, during the period 2010–2015, all the clinical trials of potential medicines for treating AD failed and were terminated after reaching phase three [53]. Recently, Biogen terminated both of the phase III, ENGAGE (NCT02477800), and the EMERGE (NCT02484547) clinical trials of Aducanumab [BIIB037], since it failed to demonstrate a superior activity compared to the placebo [54][55][56]. Consequently, Biogen lost more than 5 years and USD 2.5 billion on the failed experimental drug Aducanumab [BIIB037] [55]. It is clear that R&D expenditures over time have the most impact on the overall cost of drug development [57].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/bioengineering8020030

References

- Zang, R.; Tang, I.C.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.T. Cell-based assays in high-throughput screening for drug discovery. Int. J. Biotechnol. Wellness Ind. 2012, 1, 31–51.

- Eggeling, C.; Brand, L.; Ullmann, D.; Jäger, S. Highly sensitive fluorescence detection technology currently available for HTS. Drug Discov. Today 2003, 8, 632–641.

- An, W.F.; Tolliday, N.J. Introduction: Cell-Based Assays for High-Throughput Screening; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–12.

- Kaminski, T.; Geschwindner, S. Perspectives on optical biosensor utility in small-molecule screening. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2017, 12, 1083–1086.

- Kaminski, T.; Gunnarsson, A.; Geschwindner, S. Harnessing the Versatility of Optical Biosensors for Target-Based Small-Molecule Drug Discovery. ACS Sens. 2016, 2, 10–15.

- Macarrón, R.; Hertzberg, R.P. Design and Implementation of High Throughput Screening Assays. Mol. Biotechnol. 2010, 47, 270–285.

- El Harrad, L.; Bourais, I.; Mohammadi, H.; Amine, A. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Biosensors Based on Enzyme Inhibition for Clinical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Sensors 2018, 18, 164.

- Kotlarek, D.; Vorobii, M.; Ogieglo, W.; Knoll, W.; Rodriguez-Emmenegger, C.; Dostálek, J. Compact Grating-Coupled Biosensor for the Analysis of Thrombin. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 2109–2116.

- Pourbasheer, E.; Ganjali, M.R. Recent Advances in Biosensors Based Nanostructure for Pharmaceutical Analysis. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2019, 15, 152–158.

- Hulme, E.C.; Trevethick, M.A. Ligand binding assays at equilibrium: Validation and interpretation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 161, 1219–1237.

- Kelley, B.P.; Lunn, M.R.; Root, D.E.; Flaherty, S.P.; Martino, A.M.; Stockwell, B.R. A Flexible Data Analysis Tool for Chemical Genetic Screens. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 1495–1503.

- Varma, H.; Lo, D.C.; Stockwell, B.R. High-Throughput and High-Content Screening for Huntington’s Disease Therapeutics. In Neurobiology of Huntington’s Disease: Applications to Drug Discovery; Lo, D.C., Hughes, R.E., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 121–1461.

- Cader, Z.; Graf, M.; Burcin, M.; Mandenius, C.-F.; Ross, J.A. Cell-Based Assays Using Differentiated Human Induced Pluripotent Cells; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1994, pp. 1–14.

- Mandenius, C.-F.; Ross, J.A. Cell-Based Assays Using IPSCs for Drug Development and Testing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019.

- Lee, D.W.; Doh, I.; Nam, D.-H. Unified 2D and 3D cell-based high-throughput screening platform using a micropillar/microwell chip. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 228, 523–528.

- Kelm, J.M.; Lal-Nag, M.; Sittampalam, G.S.; Ferrer, M. Translational in vitro research: Integrating 3D drug discovery and development processes into the drug development pipeline. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 26–30.

- Wildey, M.J.; Boyd, H.; Dale, I.L.; Dahl, G.; Nicolaus, F.; Bowen, W.; Lindmark, H. Chapter Five—High-Throughput Screening, in Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry; Goodnow, R.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 149–195.

- Fu, J.; Na, Z.; Peng, B.; Uttamchandani, M.; Yao, S.Q. Accelerated cellular on- and off-target screening of bioactive compounds using microarrays. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 14, 59–64.

- Nierode, G.; Kwon, P.S.; Dordick, J.S.; Kwon, S.-J. Cell-Based Assay Design for High-Content Screening of Drug Candidates. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 213–225.

- Rue, S.M.; Anderson, P.W.; Gaylord, M.R.; Miller, J.J.; Glaser, S.M.; Lesley, S.A. A High-Throughput System for Transient and Stable Protein Production in Mammalian Cells. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2025, pp. 93–142.

- Damavandi, N.; Raigani, M.; Joudaki, A.; Davami, F.; Zeinali, S. Rapid characterization of the CHO platform cell line and identification of pseudo attP sites for PhiC31 integrase. Protein Expr. Purif. 2017, 140, 60–64.

- Kitchen, P.; Day, R.E.; Taylor, L.H.J.; Salman, M.M.; Bill, R.M.; Conner, M.T.; Conner, A.C. Identification and Molecular Mechanisms of the Rapid Tonicity-induced Relocalization of the Aquaporin 4 Channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 16873–16881.

- Salman, M.M.; Kitchen, P.; Woodroofe, M.N.; Brown, J.E.; Bill, R.M.; Conner, A.C.; Conner, M.T. Hypothermia increases aquaporin 4 (AQP4) plasma membrane abundance in human primary cortical astrocytes via a calcium/transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4)-and calmodulin-mediated mechanism. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017, 46, 2542–2547.

- Kitchen, P.; Salman, M.M.; Halsey, A.M.; Clarke-Bland, C.; Macdonald, J.A.; Ishida, H.; Vogel, H.J.; Almutiri, S.; Logan, A.; Kreida, S.; et al. Targeting Aquaporin-4 Subcellular Localization to Treat Central Nervous System Edema. Cell 2020, 181, 784–799.

- Sylvain, N.J.; Salman, M.M.; Pushie, M.J.; Hou, H.; Meher, V.; Herlo, R.; Peeling, L.; Kelly, M.E. The effects of trifluoperazine on brain edema, aquaporin-4 expression and metabolic markers during the acute phase of stroke using photothrombotic mouse model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183573.

- Wyler, M.R.; Smith, D.H.; Cayanis, E.; Többen, U.; Aulner, N.; Mayer, T. Cell-Based Assays to Probe the ERK MAP Kinase Pathway in Endothelial Cells. In Advanced Structural Safety Studies; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 486, pp. 29–41.

- Bettens, K.; Sleegers, K.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Current status on Alzheimer disease molecular genetics: From past, to present, to future. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, R4–R11.

- Cookson, M.R.; Bandmann, O. Parkinson’s disease: Insights from pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, R21–R27.

- Haggarty, S.J.; Silva, M.C.; Cross, A.; Brandon, N.J.; Perlis, R.H. Advancing drug discovery for neuropsychiatric disorders using patient-specific stem cell models. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 73, 104–115.

- Fröhlich, F.; Kessler, T.; Weindl, D.; Shadrin, A.; Schmiester, L.; Hache, H.; Muradyan, A.; Schütte, M.; Lim, J.-H.; Heinig, M.; et al. Efficient Parameter Estimation Enables the Prediction of Drug Response Using a Mechanistic Pan-Cancer Pathway Model. Cell Syst. 2018, 7, 567–579.e6.

- Fang, Y. Ligand–receptor interaction platforms and their applications for drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2012, 7, 969–988.

- Stoddart, L.A.; White, C.W.; Nguyen, K.; Hill, S.J.; Pfleger, K.D. Fluorescence-and bioluminescence-based approaches to study GPCR ligand binding. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 3028–3037.

- Buratti, E.; Romano, M.; Baralle, F.E. TDP-43 high throughput screening analyses in neurodegeneration: Advantages and pitfalls. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 56, 465–474.

- Ballatore, C.; Brunden, K.; Crowe, A.; Huryn, D.; Lee, V.; Trojanowski, J.; Smith, A.; Huang, R.; Huang, W.; Johnson, R.; et al. Aminothienopyridazine Inhibitors of Tau Assembly. Patent WO2011037985 A8, 31 March 2011.

- Brunden, K.R.; Ballatore, C.; Crowe, A.; Smith, A.B., III; Lee, V.M.Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Tau-directed drug discovery for Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies: A focus on tau assembly inhibitors. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 223, 304–310.

- De Mello, C.P.P.; Rumsey, J.; Slaughter, V.; Hickman, J.J. A human-on-a-chip approach to tackling rare diseases. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 2139–2151.

- Khan, N.I.; Song, E. Lab-on-a-Chip Systems for Aptamer-Based Biosensing. Micromachines 2020, 11, 220.

- Moffat, J.G.; Vincent, F.; Lee, J.A.; Eder, J.; Prunotto, M. Opportunities and challenges in phenotypic drug discovery: An industry perspective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 531–543.

- Varma, H.; Lo, D.C.; Stockwell, B.R. High Throughput Screening for Neurodegeneration and Complex Disease Phenotypes. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2008, 11, 238–248.

- MaCarron, R.; Banks, M.N.; Bojanic, D.; Burns, D.J.; Cirovic, D.A.; Garyantes, T.; Green, D.V.S.; Hertzberg, R.P.; Janzen, W.P.; Paslay, J.W.; et al. Impact of high-throughput screening in biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011, 10, 188–195.

- Pereira, A.D.; Williams, A.J. Origin and evolution of high throughput screening. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 152, 53–61.

- Olesen, J.; Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.Y.; Wittchen, H.; Jonsson, B.H.; on behalf of the CDBE2010 Study Group; Council, T.E.B. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur. J. Neurol. 2011, 19, 155–162.

- Nutt, D.J. The full cost and burden of disorders of the brain in Europe exposed for the first time. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 715–717.

- Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.; Jacobi, F.; Allgulander, C.; Alonso, J.; Beghi, E.; Dodel, R.; Ekman, M.; Faravelli, C.; Fratiglioni, L.; et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 718–779.

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.; Dolman, D.E.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and function of the blood–brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 13–25.

- Salman, M.M.; Marsh, G.; Kusters, I.; Delincé, M.; Di Caprio, G.; Upadhyayula, S.; De Nola, G.; Hunt, R.; Ohashi, K.G.; Gray, T.; et al. Design and Validation of a Human Brain Endothelial Microvessel-on-a-Chip Open Microfluidic Model Enabling Advanced Optical Imaging. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 573775.

- Pardridge, W.M. The blood-brain barrier: Bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx 2005, 2, 3–14.

- Ghose, A.K.; Viswanadhan, V.N.; Wendoloski, J.J. A Knowledge-Based Approach in Designing Combinatorial or Medicinal Chemistry Libraries for Drug Discovery. 1. A Qualitative and Quantitative Characterization of Known Drug Databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1999, 1, 55–68.

- Lipinski, C.A. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2000, 44, 235–249.

- Wouters, O.J.; McKee, M.; Luyten, J. Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New Medicine to Market, 2009–2018. JAMA 2020, 323, 844–853.

- DiMasi, J.A.; Grabowski, H.G.; Hansen, R.W. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. J. Health Econ. 2016, 47, 20–33.

- Cummings, J.L.; Morstorf, T.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: Few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 37.

- Mehta, D.; Jackson, R.; Paul, G.; Shi, J.; Sabbagh, M. Why do trials for Alzheimer’s disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective for 2010-2015. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2017, 26, 735–739.

- Biogen. 221AD302 Phase 3 Study of Aducanumab (BIIB037) in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02484547 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Bloomberg. Biogen to Spend $2.5 Billion Before Alzheimer’s Drug Results, in 2015. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-27/biogen-to-spend-2-5-billion-before-alzheimer-s-drug-results (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Biogen. 221AD301 Phase 3 Study of Aducanumab (BIIB037) in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02477800 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- A DiMasi, J.; Hansen, R.W.; Grabowski, H.G. The price of innovation: New estimates of drug development costs. J. Health Econ. 2003, 22, 151–185.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!