Patients with psoriasis have a poor nutritional status, and they are at risk of nutrient deficiencies. However, these health aspects are not routinely assessed and may increase the risk of malnutrition among these patients. Therefore, additional assessments, such as body composition and dietary assessment, are needed to determine the nutritional status to provide a suitable intervention.

1. Introduction

Plaque psoriasis or psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune skin disease affecting 60 million people worldwide [

1,

2]. It is characterised by erythematous scaly patches covering large amounts of the skin, mainly on the extensor surfaces, such as the elbows and knees, as well as the scalp, trunk and gluteal fold [

3]. Disease severity using the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score is widely used in research, but not routinely, to assess skin involvement, location, thickness, scaling and redness [

4]. The pathogenesis of psoriasis involves genetic predisposition, a dysregulated immune response, inflammatory pathways and environmental factors such as obesity and nutrition [

5,

6,

7]. Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome (MetS), obesity, autoimmune thyroid disease, gout, mental health diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, chronic kidney diseases and even malignancy [

8], leading to an economic burden, poor quality of life and reduced productivity [

9,

10].

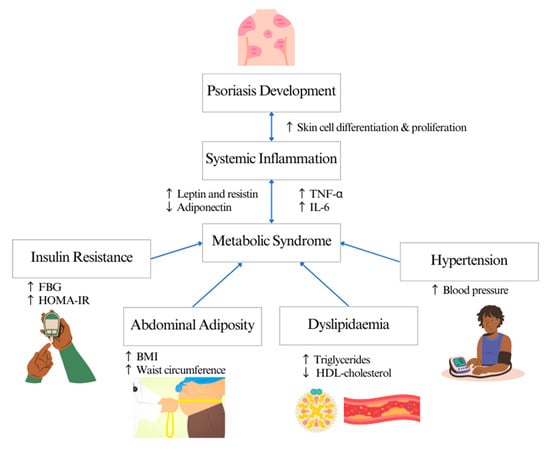

MetS is the most common comorbidity in patients with psoriasis, with a prevalence rate of 20–50% [

11]. In a clinical setting, physicians often use one of these screening criteria distributors to diagnose MetS: the World Health Organization (WHO) [

12], the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) [

13] and the European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR) [

14,

15]. The main clinical feature of MetS is insulin resistance but measuring circulating insulin is not routine in clinical practice. The common surrogate measures for insulin resistance and its complications are waist circumference for abdominal adiposity, triglycerides (TG) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels for dyslipidaemia, fasting blood glucose for diabetes mellitus and blood pressure for hypertension [

16]. The mechanism linking psoriasis and MetS is still unclear. Th1 and Th17 T-cell-mediated inflammation are associated with the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-alpha, which enter the systemic circulation, inducing metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, thus increasing the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [

17,

18]. Meanwhile, abdominal adiposity in patients with psoriasis induces inflammation by mediating pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines such as leptin and resistin, contributing to the development of insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia and vascular dysfunction [

19] (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Systematic inflammation linking psoriasis and metabolic syndrome.

All these measured parameters form part of the nutritional assessment, which is routinely performed in clinical practice by dietitians to identify nutritional problems or risks to optimise nutritional management and determine the nutritional status of an individual. Other measures include anthropometrical indices, biochemical evaluation, clinical evaluation and food and diet history. Measurement of anthropometry includes the weight, body mass index (BMI), skinfold measurement and body composition. However, recently, body composition using a bioimpedance analysis (BIA), dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and computed tomography (CT) has been used to measure adiposity [

20]. Meanwhile, biochemical parameters that are usually assessed include the complete blood count, electrolytes and liver parameters [

21,

22]. Clinical evaluation determines a patient’s inability to chew or swallow, loss of appetite, metabolic stress due to infection, gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhoea and nausea, fluid retention and clinical signs on the skin indicating micronutrient deficiency, as well as functional assessment to determine muscle function [

22]. Finally, the assessment of diet history involves food and beverage intake and the influence of cultural or religious factors, also taking into account allergies, food preference, supplement intake and intolerance to estimate total energy, carbohydrate, fat and protein intake [

21]. Therefore, a comprehensive nutrition assessment is pertinent to determine the nutritional status of patients.

Although patients with psoriasis with MetS are more likely to be over-nourished due to obesity, the excess energy intake may be mainly from calorie-dense low-nutrient foods. A Brazilian study among male patients with psoriasis and patients with psoriasis arthritis aged between 19 and 60 years reported a high intake of calories, total fat and protein exceeding the recommended levels and a lower intake of fibre and minerals [

23]. These results were similar to an Italian study assessing seven days of dietary intake whereby patients had a higher carbohydrate, total fat and polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) intake and lower fibre intake compared to controls [

24]. Meanwhile, in a Turkish case-control study, an association between low vitamin E intake and severity in patients was observed [

25]. Although patients had higher BMI compared to controls, their overall intake was significantly lower compared to controls. It is evident that patients with psoriasis, particularly those with MetS, have a poor nutritional status and poor-quality diet that may lead to nutritional deficiencies. It is important for patients attending a clinic to complete a thorough nutritional assessment.

2. Metabolic Syndrome Screening and Nutritional Status of Psoriasis

Patients with psoriasis were mostly overweight or obese. An increased body mass could potentially decrease the drug distribution in the body, reducing the effectiveness of systemic or biological treatment [49,50]. In addition, a higher BMI also increases psoriasis severity [50,51,52] and induces inflammation [24,53], thus increasing the risk of comorbidities in patients.

Therefore, early detection of comorbidities and weight loss has been recommended for patients with psoriasis [

54,

55,

56]. In the included studies, obesity was assessed by BMI, whereas abdominal obesity was assessed using the waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. BMI is widely used in clinical settings as it is a convenient index to determine nutritional status. However, it has its limitations, as a nutritional status determined through BMI does not distinguish the difference between fat mass and muscle mass, as it measures excess weight rather than excess fat. As BMI cannot determine the distribution of body fat [

57], waist circumference is a better predictor of adiposity compared to BMI and is an important measure of central obesity, a predisposing factor for psoriasis [

58]. A high volume of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is associated with chronic inflammation [

59]. White adipose tissue that is mostly formed as VAT induces inflammation and cell dysfunction, reduces insulin sensitivity and disrupts glucose and lipids by releasing proinflammatory adipokines [

53,

60]. However, it is recommended that both BMI and waist circumference are interpreted together to determine those who are abdominally obese with increased risks [

61].

It was also observed that most studies did not classify waist circumference according to sex, leading to a possibility of misclassification. Waist circumference is also prone to measurement errors if it is not measured by trained staff. Therefore, there is potentially a need for a more reliable assessment of body composition to provide better data on the nutritional status, such as the use of bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), a safe, inexpensive, non-invasive technique that can distinguish the fat and muscle mass. The associated bioelectrical device employs a small electric current to estimate the resistance and reactance of various tissues in the body. Areas with high fat stores will show a high impedance reading compared to areas with high muscle stores that largely store body water [

62]. It is also pertinent to assess the appendicular muscle mass due to an increased risk of sarcopenic obesity, particularly in older adults [

63,

64]. A study on patients with chronic plaque psoriasis found an association with myosteatosis and not sarcopenia, but the sample size in this study was small and the mean age of respondents was 45 years, which warrants further investigation in this population [

65]. Meanwhile, several other studies have shown that sarcopenic obesity may also increase the risk of MetS [

66,

67,

68], which poses a concern, stressing the importance of body composition measures.

Biochemical parameters that were mainly assessed were fasting blood glucose, HDL cholesterol and TG. Several studies also assessed the complete lipid profile including total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol. However, not all studies classified HDL cholesterol according to sex. There was a 16.6% increased risk of psoriasis in those with low HDL and the risk was higher in females, which was 16.9% [

69]. Therefore, classification according to sex is necessary.

Although insulin resistance was not compulsory to define MetS, a few studies assessed this using various indexes. One of them was HOMA-IR, whereby the measured fasting insulin was multiplied by fasting blood glucose and a value of <2.5 was considered part of the normal range [

70]. Although this method is simple, the values in subjects treated with insulin might not be accurate [

71]. C-peptide was also used in a study to calculate the HOMA-IR and this is used interchangeably with fasting insulin as it has a longer half-life compared to insulin. A value less than 0.2 nmol/L indicates the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus and it is also a marker for microvascular and macrovascular complications [

72]. However, both measures were mainly used to determine insulin resistance in patients with psoriasis [

73,

74].

In addition, the quantitative insulin-sensitivity check (QUICKI) was also determined by log transforming values of fasting glucose and the fasting insulin level with a cut-off of <0.33 for insulin resistance [

75]. This index is consistent and precise but there are significant variations in the normal range based on the assays performed in the laboratory [

71]. The OGTT was also performed in some studies to assess insulin sensitivity using the Matsuda index. The index is calculated from plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in the fasting state and during the OGTT [

73]. A value of < 4.3 is used to predict insulin resistance. Although this index represents both hepatic and peripheral tissue sensitivity, it has a weak correlation with insulin resistance in those with diabetes [

71].

Other biochemical parameters such as apolipoprotein levels were measured to determine cardiovascular risk in patients. The ratio of apolipoprotein B (ApoB) to apolipoprotein AI (ApoAI) is a marker for lipid disturbances as ApoAI is associated with HDL particles and it can predict the risk of myocardial infarction [

76,

77]. As patients with psoriasis have a greater risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, ApoB has been demonstrated as a better predictor for cardiovascular disease risk compared to LDL [

78,

79]. Other parameters related to cardiovascular risk such as serum homocysteine, platelets and fibrinogen were also assessed. Elevated homocysteine levels have also been associated with severity of psoriasis. Meanwhile, platelet activation has been associated with endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and immune function in patients with psoriasis [

80]. An increased level of fibrinogen has also been associated with severity in patients with psoriasis [

81].

Adiponectin and c-reactive protein (CRP) were assessed as inflammatory markers—increased levels were usually associated with the severity of psoriasis [

86,

87]. Meanwhile, higher levels of ghrelin were associated with an improved psoriasis severity score in a mouse model [

88], and have also been assessed to determine the efficacy of biologics, which were also measured in the studies included [

89]. Other biochemical markers assessing kidney functions (e.g., urea and creatinine) and liver function (e.g., alanine transaminase and aspartate aminotransferase) were also measured in several studies. Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk of developing chronic kidney failure as a result of psoriatic inflammation [

90,

91].

Clinical parameters that were assessed were mainly blood pressure, carotid intima thickness and epicardial fat thickness. Blood pressure is one of the most important clinical markers to define MetS, as hypertension is a cardiovascular risk factor and psoriasis is reported to be associated with an increased risk of hypertension [

97,

98]. Meanwhile, the carotid intima and epicardial fat thickness are markers for atherosclerosis and coronary artery diseases, respectively, and they are associated with visceral adiposity in patients with psoriasis [

99,

100].

It was observed that most of the patients with psoriasis in the studies included were either overweight or obese with abdominal adiposity. Studies that measured serum vitamin D showed that patients with psoriasis were at risk of vitamin D deficiency related to poor dietary intake or a lack of exposure to sunlight [

101]. Although the aim of these studies was to determine the MetS status in these patients, some of the nutritional assessments performed were useful in determining the nutritional status of patients with psoriasis, such as the BMI, waist circumference and vitamin D status.

Besides vitamin D deficiency, patients with psoriasis could also be at risk of other nutritional deficiencies related to their dietary practices. An Italian study reported the presence of eating disorders among patients with psoriasis [

102]. Meanwhile, other studies have reported an imbalance of nutrient intake related to a diet high in fat and simple carbohydrates and low in fibre [

23,

24]. Dietary intake is related to psoriasis severity whereby a diet high in saturated fat and red and simple sugar is associated with inflammation. Meanwhile, vitamin D, vitamin B12, vitamin A and selenium play an important role in improving severity [

6,

103,

104]. Therefore, dietary assessment is pertinent to determine the nutritional status of patients with psoriasis. Several dietary assessment methods can be used to determine the dietary intake of patients with psoriasis. Trained dietitians or researchers could conduct a quick 24-h multiple-pass recall by asking open-ended questions to patients to enquire about actual intake in a specific period. Although this recall may rely on the patient’s ability to recall intake, a trained individual may be able to prompt patients to gather sufficient information in multiple passes such as dietary recall for the past 24-h, followed by details of food and beverages consumed, the portion size or ingredients and a summary of the entire day’s intake. This method is used daily in busy clinical practices by dietitians or nutritionists [

105,

106].

Patients with psoriasis who are overweight and obese are more likely to develop MetS. Therefore, early dietary intervention is needed to improve the nutritional status, reduce the risk of metabolic disorders and improve the effectiveness of treatments [

103,

104,

109,

110]. Dietary recommendations are often individualised based on the patients’ comorbidities. Obese or overweight patients with psoriasis without MetS would usually be advised on caloric restriction and weight reduction. A low-calorie diet lowers BMI and reduces inflammation and oxidative stress, thus improving the response to treatment [

54,

110]. Meanwhile, patients with MetS will require a more in-depth dietary consultation based on their elevated biochemical and clinical parameters. Besides caloric restriction and weight reduction, recommendations also include the restriction of total fat and refined carbohydrates. A Mediterranean diet is more appropriate for these patients as it is a balanced diet, as well as high in antioxidants, polyphenols and mono-unsaturated fats. The anti-inflammatory effect of the diet has been associated with reducing coronary heart disease, increasing immunity and reducing the inflammatory response [

103,

111]. Dietary supplementation, particularly with vitamin D, could also be recommended for patients with deficiency [

103].

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, patients with psoriasis are at risk of MetS and an increase in body mass and adiposity may play a role. Although anthropometry measurement is employed to determine the nutritional status, it is also evident that patients with psoriasis may have a risk of nutrient deficiencies, which is not assessed in clinical practice or research settings. Additional assessments, such as body composition and dietary intake, need to be performed to determine the nutritional status of these patients and assess their health risk, and subsequently devise a suitable intervention.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu15122707