Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Obstetrics & Gynaecology

Uterine cervical cancer (CC) is a complex, multistep disease primarily linked to persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV).

- cervicovaginal microbiome

- human papillomavirus

- cervical cancer

1. Introduction

Uterine cervical cancer (CC) remains a major public health problem, with a significant number of new cases and deaths annually [1]. Persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, particularly high-risk genotypes (HR-HPV), is the most common cause of CC [2]. It is undeniable that HR-HPV infection is essential for CC formation and progression, but not sufficient alone. Moreover, drivers of the transition state between HPV acquisition, spacing, and persistence are poorly understood [3].

The cervicovaginal microbiome (CVM) has been considered essential to the female vaginal flora [4]. In most healthy women, the CVM is dominated by Lactobacillus spp., which benefits the host through symbiotic relationships [5,6]. Lactobacillus spp. depletion can lead to CVM dysbiosis, which may enhance tumor development through several mechanisms, such as promoting chronic inflammation, dysregulating the immune system, and producing genotoxins [7].

Recently, mounting evidence has suggested an interaction between HPV, the CVM, and CC progression [8]. On the one hand, HPV infection can induce changes in the cervicovaginal microenvironment [9]. Consequently, this can lead to CVM dysbiosis and cancer. On the other hand, abnormalities in the cervicovaginal flora may change vaginal pH, release bacteriocin, and disrupt the mucosal layer. As a result, dysbiosis may contribute to HPV-related CC by interfering with HPV infection, binding, internalization, integration, gene expression, and telomerase activation [10]. Several studies have reported that women with HPV infection and CVM dysbiosis show high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs) or cancer [11,12], which may require closer follow-up and advanced treatment.

Bacteriotherapy, especially probiotics, has attracted enormous interest in CC prevention and treatment due to their antitumor activities [13,14,15,16]. Probiotics may become the best choice for controlling the complex interaction between the CVM, HPV, and cervical carcinogenesis.

2. Human Papillomavirus

2.1. Structure and Genome

HPV is the most common cause of sexually transmitted infections in women. This virus belongs to a group of nonenveloped and double-stranded DNA viruses [17]. The HPV genome is circular DNA containing eight open reading frames and divided into three encoded regions: an early region encoding a nonstructural protein (E1, E2, and E4–E7) for replication, a late region encoding viral capsid proteins (L1 and L2) for viral assembly, and a long control region (LCR) or upstream regulatory region [18].

There are >200 types of HPV, and ~40 genotypes infect the mucosal epithelium in the anogenital tract. Based on the association between these types and carcinogenicity, they are categorized into low-risk HPVs (HPV6, 11, 40, 42–44, and 54) and HR-HPVs (HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59) [19]. For example, HPV6 and HPV11, low-risk HPVs, are related to benign warts. In contrast, HPV16 and HPV18, HR-HPVs, can represent intraepithelial neoplasia with the potential for malignant progression [20].

2.2. Life Cycle of HPV

The most common HPV infections are caused by sexual intercourse when the vaginal and cervical epithelia are exposed to HPV through a microwound [21]. After entering basal keratinocytes, the viral genome moves to the nucleus and is maintained as episome DNA with a low copy number (50–100 copies per cell) [22].

In the early region, E2 is considered a regulator factor, whereas E6 and E7 are critical in inhibiting host tumor suppressor genes and oncogenic transformation [23]. Notably, the formation of an E1-E2 complex is required for the stable binding of the E1 helicase to the LCR ori site and controls the transcriptional levels of E6 and E7 viral oncogenes [24]. After integrating the HPV genome into the host DNA, the connection between E1 and E2 breaks, and E2 expression is lost. As a result, E6 and E7 expression is upregulated, which leads to the inactivation of tumor suppressor proteins p53 and pRb, respectively. This condition will promote malignant transformation in the cervix [25,26,27,28,29].

Until keratinocyte differentiation, the productive stage of the viral life cycle occurs by activating the late promoter (L1 and L2) and late viral gene expression (E4 and E5). Moreover, E1 and E2 expression increases HPV DNA amplification between 100 and 1000 episomal copies per cell [30,31]. Viral particles were then released from the uppermost layers of the stratified epithelium. There are ~3 weeks from infection to the release of the virus in which the virus can evade the immune system, and the appearance of lesions can occur after weeks to months [32].

2.3. HPV and Host Immune Responses

The host immune system, including the innate and adaptive immune systems, plays a vital role in clearing or controlling the infection and eliminating HPV-induced lesions.

2.3.1. HPV and Innate Immune Response

The essential step of the innate immune response is to detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by receptors located on the surface of sensor cells. During the early stages of HPV infection, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) can recognize HPV and activate a cascade of antiviral signaling pathways to defend against its invasion. These pathogen sensors can detect DNA (known as DNA sensors: absent in melanoma 2 [33], interferon (IFN)-γ inducible protein 16 [34,35], Toll-like receptor 9 [36], and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase [37,38]) or RNA (known as RNA sensors: Toll-like receptor 3 [36], retinoic acid-inducible gene I [39], and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 [40]) in the cytoplasm or nucleus. One of the most important downstream reactions is the induction of IFN signaling, including types I and III IFNs, which stimulates the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) signaling cascade, enhances IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) expression, and results in HPV clearance [41,42,43,44].

Several types of immune sentinels (sensor cells) exist in the innate system, such as dendritic cells, Langerhans cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and keratinocytes. Among them, keratinocytes target cells of HPV in early infection and play an essential role in response to the recognition between PRRs and PAMPs. Keratinocytes can detect various HPV-related patterns and secrete various cytokines and chemokines. These cytokines and chemokines promote immune responses and recruit more immune cells to the HPV-related microenvironment [17,45].

2.3.2. HPV and the Adaptive Immune Response

The adaptive immune system includes cell-mediated immune responses and antibody-mediated humoral immunity. The cell-mediated system is vital for destroying virus-infected cells, and the antibody-mediated system is responsible for clearing free pathogen particles from body fluids [46]. During HPV invasion, CD4+ T helper 1 (Th1) cells can detect HPV E6, E7, and E2 and induce cytotoxicity by activating CD8+ T cells and releasing interleukin (IL)-2 and IFN-γ [47]. It is agreed that whereas innate responses play a role in early HPV clearance, adaptive responses are essential to determining and eliminating HPV-induced lesions, particularly effector T cells [46].

A meta-analysis by Litwin et al. [48] supported the important role of T-cell populations in the outcome of cervical HPV infections. According to this study, helper and killer T cells are found at lower levels in low- and high-grade cervical lesions than in normal tissue, suggesting that the virus evades immune detection in patients with persistent lesions. Moreover, Foxp3+ and CD25+ regulatory T-cell (Treg) infiltration was high in precancerous HPV-related lesions, and longitudinal data showed improved outcomes with lower Treg levels.

2.3.3. HPV and Immune Suppression

Even if the immune reaction seems perfect and can clear most HPV infections, HPV has several immune evasion mechanisms and can facilitate cancer progression (Figure 1). First, most HPVs in the intraepithelial layer provide almost no viremia, release few proteins, induce less inflammation, and cause few host cell deaths [47,49]. Therefore, HPV can often prevent itself from being recognized by sensors.

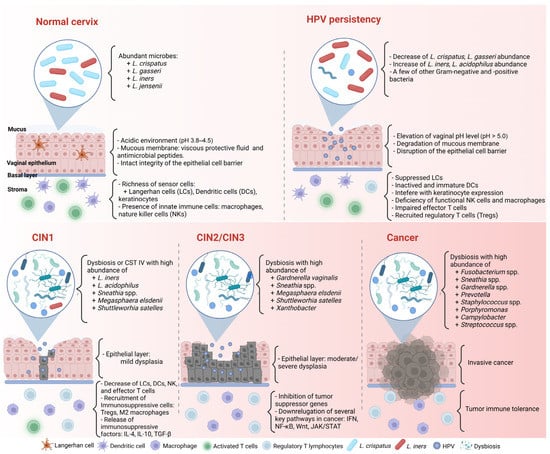

Figure 1. Complex association between HPV infection, the CVM, and cancer formation in the cervicovaginal microenvironment. CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 30 March 2023).

Second, HPV can alter host gene, transcript factor, or protein expression to evade the immune response. For example, HPV blocks IFN signaling by inhibiting the activity of the IFN regulatory factors, interfering with the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, and downregulating the IFN-κ and ISG expressions. Moreover, HPV deregulates the activity of transcription factors, particularly nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), to repress proinflammatory cytokine production. NF-κB is one of the members of the NF-κB family responsible for controlling cell proliferation and apoptosis through the NF-κB/IFN signaling pathway. HR-HPV can eradicate the inhibitory effect of the immune system and lead to persistent infection by decreasing NF-κB activation [50,51].

Third, the HPV-related microenvironment can inhibit the infiltration of helper and cytotoxic T cells while recruiting more immunosuppressive cells, such as M2 macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and Tregs [48,52]. Tregs are related to downregulated responses to exogenous antigens. When Tregs are recruited to a tumor, they suppress the adaptive immune response and promote HPV-related lesion formation. M2 macrophages and MDSCs can enhance HPV-associated tumor progression by inhibiting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, attracting Tregs, and producing immunosuppressive factors such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [53].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms11061417

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!