Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Fanny Huang and Version 3 by Fanny Huang.

Zingiber officinale Roscoe. (ginger) is a widely distributed plant with a long history of cultivation and consumption. Ginger can be used as a spice, condiment, food, nutrition, and as an herb. Significantly, the polysaccharides extracted from ginger show surprising and satisfactory biological activity, which explains the various benefits of ginger on human health, including anti-influenza, anti-colitis, anti-tussive, anti-oxidant, anti-tumor effects.

- Zingiber officinale Roscoe

- polysaccharide

- Ginger Polysaccharides

- structural characteristic

- biological activity

1. Introduction

Ginger is a perennial herb of the Zingiberaceae family, scientifically named Zingiber officinale Roscoe. [1][2]. As early as the 18th century, Europeans began using ginger to make beer, candy, bread, biscuits, and so on. It is also an indispensable seasoning in Japanese cuisine, Korean food, and Chinese food [3][4]. Therefore, it is a widely distributed plant with a long cultivation history. It is now mainly cultivated and used in India, Nigeria, China, Burma, Indonesia, Australia, Japan, Sri Lanka, Germany, Greece, Arabia, and other countries. Among them, India, Nigeria, and China are the main producers of ginger, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations statistical database (FAO) in 2022 [5][6]. As an important plant with economic, ornamental, and even edible and medicinal values, it has attracted attention from multiple scientific fields. It is a rich source of nutrients such as protein, vitamins, minerals, fat, and crude fiber [7][8][9]. It has attracted increasing interest from nutrition researchers and health-conscious consumers.

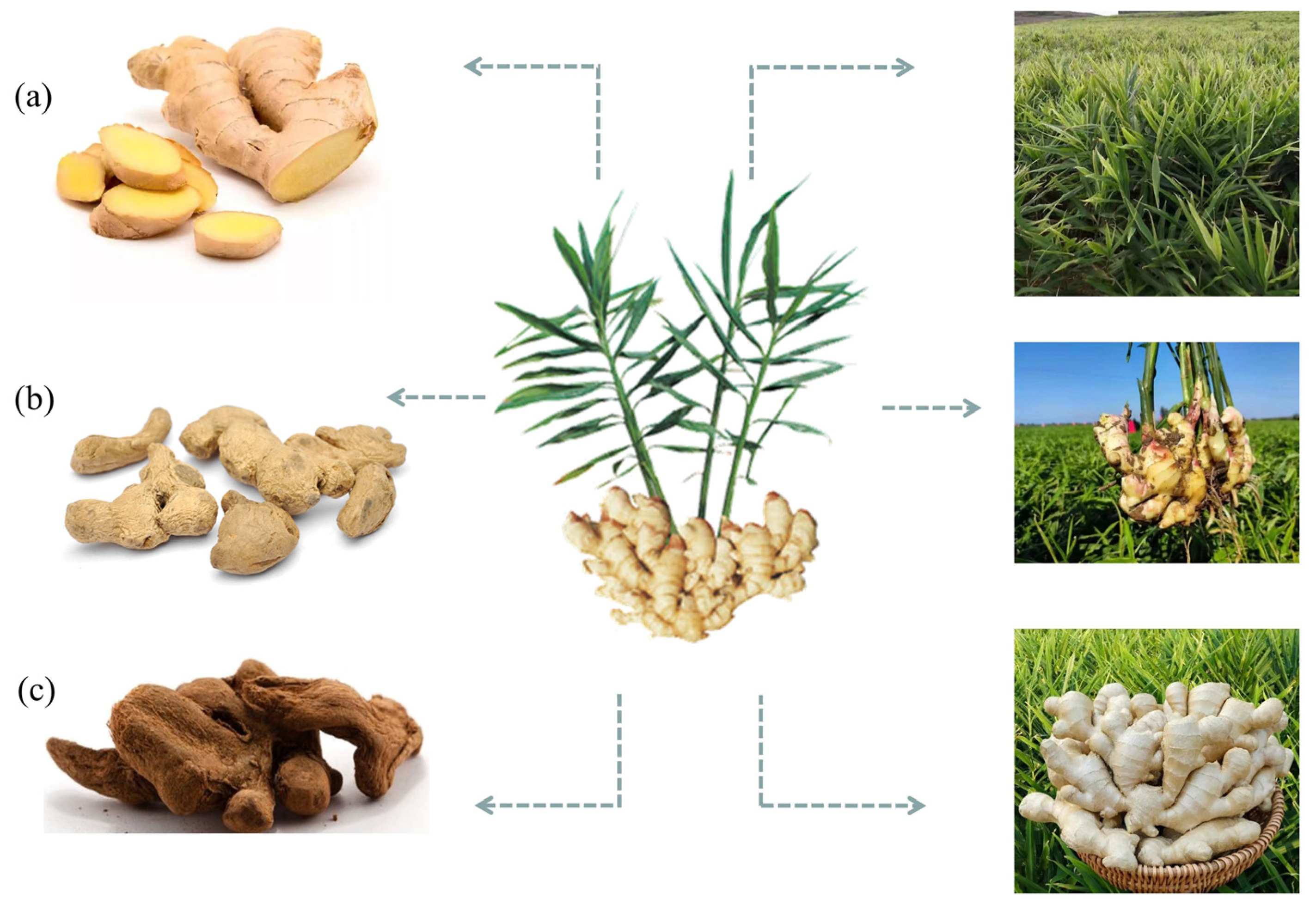

In its long history of application and consumption, ginger has been fully utilized and deeply developed as a nourishing food and traditional oriental medicine [10][11][12]. As a “medicinal food homology” plant, ginger and its active ingredients are not only used as delicious food, but also as effective empirical medicine [13][14]. Ginger can be used as tea or health drinks and is traditionally used to treat diseases such as colds, vomiting, and fatigue [15][16][17]. In Africa, ginger essential oil is commonly used to relax muscles or treat muscle and joint pain, swelling, and inflammation. It can also be dripped in water and gargled to relieve toothache. In addition, ginger is an important part of Ayurveda preparation “Trikatu”. Trikatu can be used in combination with other drugs to treat asthma, bronchitis, dysentery, fever, and intestinal infections [18]. Due to its health benefits such as enhancing immunity and promoting energy metabolism, ginger is widely used as a restorative supplement or medicinal food in folk [19][20]. Officially, the Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2020 version includes three related products, including Shengjiang (fresh ginger), Ganjiang (dried ginger), and Paojiang (fried ginger) (Figure 1). Therefore, the nutritional and medicinal value of ginger has been widely recognized, meeting the needs of consumers for a healthy diet, nutritional intake, and dietary treatment.

Figure 1. A plant image of Zingiber officinale Roscoe. (ginger). (a) Shengjiang (fresh ginger); (b) Ganjiang (dried ginger); (c) Paojiang (fried ginger).

It is widely believed that ginger can be used as a nutritious vegetable or natural functional food. As ginger contains important phytochemicals and biologically active ingredients, such as volatile oil, curcumin, flavonoids, and polysaccharides, it is increasingly popular in daily diet [21][22][23][24]. Gingerol, as an important source of ginger’s pungent taste, endows ginger with a unique spicy taste and is also one of the main active ingredients in ginger, which is often the focus of researchers [25][26][27]. However, the macromolecular compound polysaccharides obtained from ginger exhibit surprising and satisfactory biological activities, which may explain their various benefits to human health, including anti-influenza, anti-colitis, anti-tussive, anti-oxidant, and anti-tumor effects [28][29]. Currently, various polysaccharides have been extracted from ginger through different extraction and purification methods. Due to the diversity of the chemical structure of polysaccharides in ginger, as well as their different physicochemical properties and biological activities, it has attracted more and more research interest. Ginger polysaccharides are considered safe and non-toxic. At the same time, they have a variety of beneficial functions for the body, and have a good development prospect in food, cosmetics, medicine, and other industries [30][31].

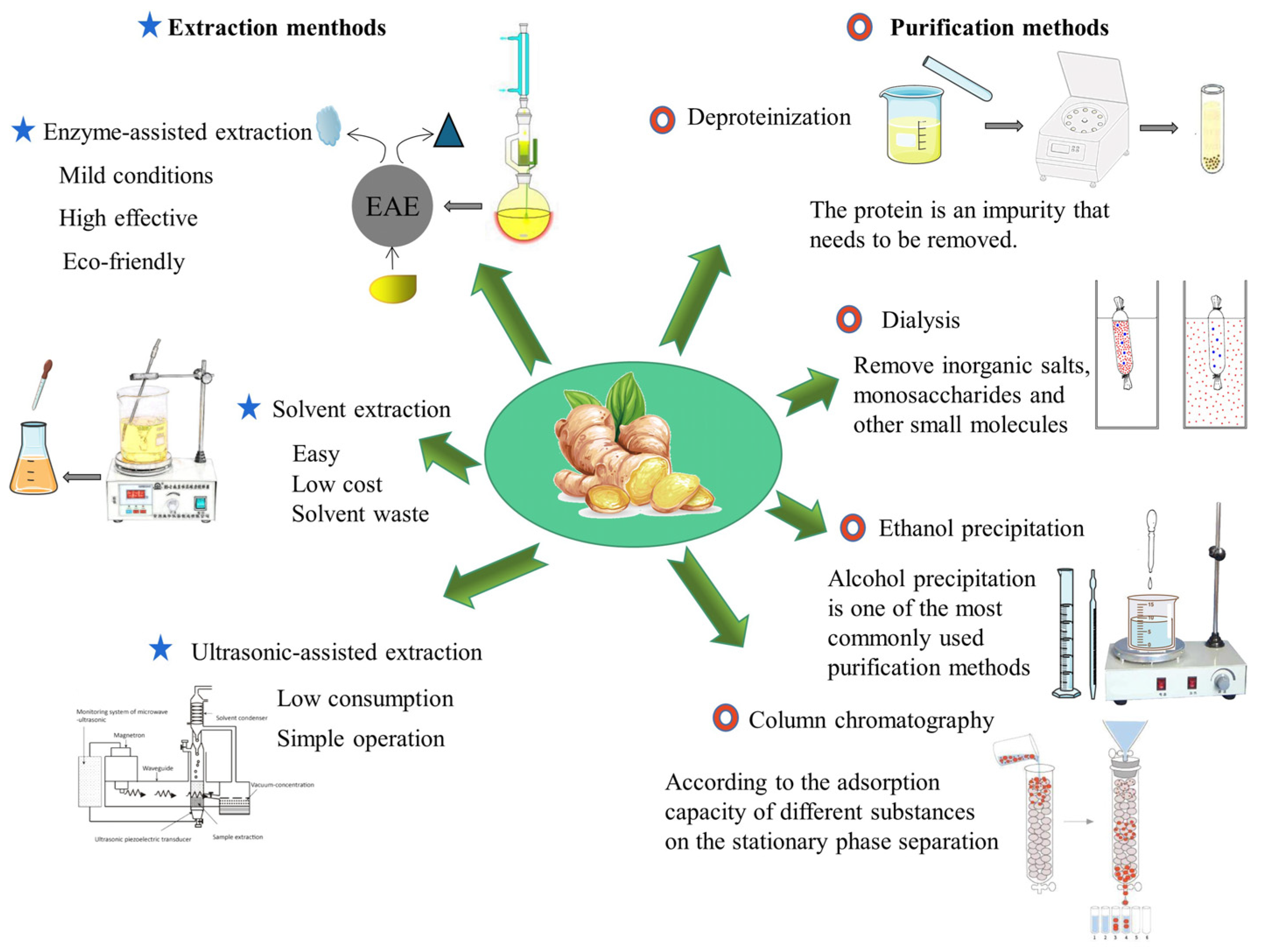

2. Extraction and Purification Methods of Ginger Polysaccharides

2.1. Extraction Methods of Ginger Polysaccharides

Effective extraction and purification of ginger polysaccharides is the main premise for studying the structures and biological activities of polysaccharides. In order to maximize the extraction efficiency of bioactive macromolecular polysaccharides from ginger, researchers have carried out a series of explorations into various extraction strategies, including the traditional extraction method of solvent extraction method (SEE), the novel extraction methods of enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE), and ultrasonic-assisted extraction (UAE). The specific information of various extraction methods is summarized in Table 1.Table 1. A summary of ginger polysaccharides extraction methods.

| Polysaccharide Fraction | Extraction Methods | Time (min) | Biological ActivitiesTemperature (°C) | Solid–Liquid Ratio (g/mL) | Total Yield (%) | Ref. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Compound Name | Molecular Weights | Monosaccharide Composition | Ref. | |||||||||

| Compound Name | In Vitro or In Vivo | Indicated Concentrations and Animal Experiments/Test System | Action or Mechanism | Ref. | |||||||||

| Ginger polysaccharide (GPS) | Complex-enzyme hydrolysis extraction | 60 min | 55 °C | 1:25 | 22.18% | [32] | |||||||

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharide 2 (GP2) | 12.619 kDa | Ara:Man:Glu:Gal = 4.78:16.70:61.77:16.75 | [32] | |||||||||

| Anti-oxidant effects | Polysaccharides from ginger stems and leaves (HWE-GSLP, UAE-GSLP, ASE-GSLP and EAE-GSLP) | In vitro | ABTS radical scavenging activity, DPPH radical scavenging activity, hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, superoxide radical scavenging activity, chelating activity, and ferric reducing power. | ABTS radical scavenging activity: These samples’ anti-oxidant capacities of ABTS, although better than those of HWE-GSLP and UAE-GSLP, did not exceed those of Ascorbic acid (VC); DPPH radical scavenging activity: ASE-GSLP (IC50 = 0.492 mg/mL) < EAE-GSLP (IC50 = 0.975 mg/mL) < UAE-GSLP (IC50 = 2.877 mg/mL) < HWE-GSLP (IC50 = 3.583 mg/mL); Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity: ASE-GSLP exhibited higher hydroxyl radical scavenging activity than the other polysaccharides; Superoxide radical scavenging activity: The experimental IC50 values followed the trend ASE-GSLP < EAE-GSLP < UAE-GSLP < HWE-GSLP. | [37][38][44] | ||||||||

| Ginger pomace polysaccharides extracted by hot water (HW-GPPs) | Hot water extraction | 120 min | 70 °C | 1:40 | 12.13 ± 1.15% | ||||||||

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharide 1 (GP1) | 6.128 kDa | Man:Glu:Gal = 4.96:92.24:2.80 | [32 | [ | 33] | |||||||

| ] | Ginger pomace polysaccharides extracted by ultrasonic–assisted (UA-GPPs) | Ultrasonic assisted extraction | 17 min | 74 °C | 1:40 | 16.62 ± 1.82% | [33 | ||||||

| Rhizome | ] | ||||||||||||

| Ginger polysaccharide (GP) | |||||||||||||

| Chelating activity: The strong Fe2+ chelating activity of EAE-GSLP and UAE-GSLP might be partially due to the high contents of–COOH and C-O groups in their structures; Ferric reducing power: In solutions of concentrations between 0.25 and 5.0 mg/mL, the reducing power of the EAE-GSLP was the greatest, followed by ASE-GSLP. | N/A | Rha:Ara:Man:Glu:Gal = 3.64:5.37:3.04:61.03:26.91 | [ | 32] | |||||||||

| Anti-tumor effects | Five purified ginger polysaccharides were obtained, namely HGP, EGP1, EGP2, UGP1 and UGP2 | In vitro | The human colon cancer HCT 116 cell line, human cervical cancer Hela cell line, human lung adenocarcinoma H1975 cell line, human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line, mouse melanoma B16 cell line | UGP1 has a strong inhibitory effect on these kinds of tumor cells such as Hela and HCT116, of which the inhibitory effect of UGP1 on the human colon cancer HCT116 cell linen is relatively high (56.843 + 2.405%), which indicates that UGP1 may be a potential drug for the treatment of colon cancer. | [ | A neutral ginger polysaccharide fraction (NGP) | Hot water extraction | 180 min | 90 °C | 1:20 | N/A | ||

| Ginger pomace | Ginger pomace polysaccharide 1 extracted by hot water (HW-GPP1) | [ | 45 | [ | 89.2 kDa | 34] | |||||||

| Man:Rha:Glu = 19.40 ± 0.06:12.27 ± 0.05:68.33 ± 0.24 | [ | 33 | ] | ] | [46] | A water extracted polysaccharides (WEP) containing fraction from ginger rhizome | Hot water extraction | 60 min | 100 °C | N/A | N/A | [35] | |

| Ginger pomace | Ginger pomace polysaccharide 2 extracted by hot water (HW-GPP2) | 939.8 kDa | Man:Rha:Glu:Xyl:Ara = 11.84 ± 0.13:9.36 ± 0.02:58.05 ± 0.07:12.68 ± 0.15:8.07 ± 0.08. | [ | |||||||||

| Non-immune mice: The CD3+, CD19+ and CD25+ cell proportions were up-regulated in thymus under MPs pretreatment. | 33 | ] | Crude ginger polysaccharides were extracted by hot water extraction (HCGP) | Hot water extraction | 240 min | 100 °C | 1:20 | 11.74 ± 0.23% | [36] | ||||

| Ginger pomace | Ginger pomace polysaccharide 3 extracted by hot water (HW-GPP3) | 1007.9 kDa | Man:Rha:Glu:Gal:Xyl:Ara = 11.33 ± 0.05:13.90 ± 0.03:50.01 ± 0.13:10.96 ± 0.13:4.73 ± 0.09:9.07 ± 0.14 | [33] | |||||||||

| Anti-colitis effects | Ginger polysaccharides (GP) | In vivo | SPF grade eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice | GP alleviated UC symptoms by inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines levels to regulate intestinal inflammation, repairing the intestinal barrier, as indicated by occludin-1 and ZOP-1, and regulating gut microbiota. | [29] | Crude ginger polysaccharides were extracted by enzyme assisted extraction (ECGP) | Enzyme assisted extraction | 120 min | 40 °C | 1:25 | 7.00 ± 0.04% | [36] | |

| Ginger pomace | Ginger pomace polysaccharide 1 extracted by ultrasonic–assisted (UA-GPP1) | 40.6 kDa | Man:Rha:Glu = 17.56 ± 0.11:7.72 ± 0.29:74.72 ± 0.27 | [33] | Crude ginger polysaccharides were extracted by ultrasonic cell grinder extraction (UCGP) | Ultrasonic cell grinder extraction | 30 min | N/A | 1:25 | 18.06 ± 0.05% | [36 | ||

| Ginger pomace | ] | ||||||||||||

| Ginger pomace polysaccharide 2 extracted by ultrasonic–assisted (UA-GPP2) | 868.1 kDa | Man:Rha:Glu:Xyl:Ara = 13.18 ± 0.05:9.03 ± 0.08:63.78 ± 0.14:8.97 ± 0.15:5.04 ± 0.08 | [ | 33] | Polysaccharides from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) stems and leaves (GSLP) | Hot water extraction | 300 min | 100 °C | 1:20 | 6.83 ± 0.54% | [37] | ||

| 36 kDa | N/A | [ | |||||||||||

| Anti-tussive effects | A water extracted ginger polysaccharides (WEP) | In vivo | Ginger pomace | Ginger pomace polysaccharide 3 extracted by ultrasonic–assisted (UA-GPP3) | 892.7 kDa | Man:Rha:Glu:Gal:Xyl:Ara = 8.32 ± 0.09:9.01 ± 0.02:59.28 ± 0.11:4.33 ± 0.03:12.19 ± 0.12:6.87 ± 0.05 | [33] | Polysaccharides from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) stems and leaves (GSLP) | Ultrasound-assisted extraction | 60 min | 50 °C | 1:20 | 8.29 ± 0.31% |

| Rhizome | A neutral ginger polysaccharide fraction (NGP) | 6.305 kDa | Glu:Gal:Ara = 93.88:3.27:1.67 | [34 | [ | 37] | |||||||

| ] | Polysaccharides from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) stems and leaves (GSLP) | Alkaline solution extraction | 120 min | 25 °C35] | |||||||||

| 25 and 50 mg/kg body weight, thirty adult healthy male TRIK strain guinea pigs | 1:20 | 11.38 ± 1.17% | [ | 37 | ] | ||||||||

| Polysaccharides from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) stems and leaves (GSLP) | Enzyme-assisted extraction | 90 min | 50 °C | 1:20 | 8.13 ± 0.85% | [37] | |||||||

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharides were extracted by hot water extraction (HGP) | A novel polysaccharide (ZOP) was extracted from Zingiber officinale Roscoe. | Ultrasonic assisted extraction | 120 min | 90 °C | 1:30 | N/A | [38] | |||||

| Ginger polysaccharide (GP) | Hot water extraction | 60 min | 100 °C | 1: 20 | N/A | [29] |

N/A means not mentioned.

2.2. Purification Methods of Ginger Polysaccharides

Ginger crude polysaccharideoften contains a variety of impurities, and it usually includes pigments, proteins, and inorganic salts. So, it needs to be purified further (Figure 2). Pigments can be removed by adsorption of macroporous resin and activated carbon. The commonly used deproteinization methods are the Sevag method, the trichloroacetic acid (TCA) method, and the enzymatic method [39][40]. Inorganic salts, monosaccharides, and other small molecular substances can be removed by dialysis and ultrafiltration. Next, the crude ginger polysaccharide solution needs to be further purified by column chromatography, and a suitable buffer solution is used as the mobile phase. Column chromatography is the most widely used method in the classification and purification of polysaccharides [41]. It can be divided into anion exchange chromatography and gel filtration chromatography. In the preparation of ginger polysaccharide GP1 and GP2, the crude ginger polysaccharide (GPS) was treated with S-8 macroporous resin column and the Sevag method to remove impurities, such as proteins, fragments, and nuclear acids, which can improve the purity and quality of GPS. Next, 0.1–1.0 mol/L NaCl solution was used as mobile phase, and DEAE-52 cellulose column was used for linear gradient elution. Subsequently, GP1 eluted with distilled water and GP2 eluted with 0.1 M NaCl buffer were further purified on Sephadex G-200 column. Finally, it was freeze dried [42]. In the preparation of neutral ginger polysaccharide (NGP), the crude ginger polysaccharide (CGP) was initially purified by DEAE-52 cellulose column, then further purified by Sephadex G-100 column, and finally freeze-dried to obtain purified NGP [34].

Figure 2. Methods for extraction and purification of ginger polysaccharides.

3. Structural Characteristics of Ginger Polysaccharides

The chemical structure of polysaccharides is the material basis of their biological activities. Ginger polysaccharides with different chemical structures have different pharmacological activities. Studying the structural characteristics of ginger polysaccharide is helpful to understand its pharmacological effects. Based on the extensive pharmacological effects of ginger polysaccharide, its structure research has been paid more and more attention. The structural characteristics of polysaccharides mainly include monosaccharide composition and sequence, molecular weight, positions of glycosidic linkages, and configuration. There are many analytical methods for the structure of polysaccharides, including not only instrumental analysis methods, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), infrared spectroscopy (IR), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), gas chromatography (GC), mass spectrometry (MS), gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), etc., but also chemical methods, including methylation analysis, acid hydrolysis, periodate oxidation, and Smith degradation, as well as biological methods, such as specific glycosidase digestion, immunological methods, etc. Polysaccharides with various monosaccharide components and chemical structures have been isolated from ginger. The main structural characteristics of ginger polysaccharide, such as molecular weight and monosaccharide composition, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Source, compound name, molecular weights, and monosaccharide composition of ginger polysaccharides.

| Rhizome | |||||||||

| A water extracted polysaccharides (WEP) containing fraction from ginger | |||||||||

| 1831.75 kDa | |||||||||

| Man:Gal = 3.1:0.9 | |||||||||

| [ | |||||||||

| 36 | |||||||||

| ] | |||||||||

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharides were extracted by enzyme assisted extraction (EGP1) | 11.81 kDa | Man:Glu:Gal:Ara = 13.3:80.7:4.0:2.0 | [36] | |||||

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharides were extracted by enzyme assisted extraction (EGP2) | 688.73 kDa | Man:Rha:Glu:Gal:Xyl:Ara = 49.4:0.8:32.6:7.7:2.5:7.0 | [36] | |||||

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharides were extracted by ultrasonic cell grinder extraction (UGP1) | 769.19 kDa | Man:Glu:Gal:Ara = 28.0:59.2:9.6:3.2 | [36] | |||||

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharides were extracted by ultrasonic cell grinder extraction (UGP2) | 1432.80 kDa | Man:Rha:Glu:Gal:Xyl:Ara = 27.2:2.2:12.0:26.3:10.5:21.7 | [36] | |||||

| WEP could reduce the number of coughs effort but did not affect the specific airway resistance of animals. | Stems and leaves | Polysaccharides from ginger stems and leaves (GSLP) by hot water extraction (HWE-GSLP) | N/A | Man:Rha:Glu:Gal:Xyl:Ara:GlcA:GalA = 1.95:17.22:4.69:38.88:5.66:28.42:1.81:1.34 | [37] | ||||

| Stems and leaves | Polysaccharides from ginger stems and leaves (GSLP) by ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE-GSLP) | N/A | Man:Rha:Glc:Gal:Xyl:Ara:GlcA:GalA = 2.11:16.06:7.518:32.44:7.764:28.43:1.74:3.95 | [37] | |||||

| Stems and leaves | Polysaccharides from ginger stems and leaves (GSLP) by alkaline solution extraction (ASE-GSLP) | N/A | Man:Rha:Glc:Gal:Xyl:Ara:GlcA:GalA = 2.20:16.24:7.453:34.09:6.36:26.72:1.98:4.96 | [37] | |||||

| Stems and leaves | Polysaccharides from ginger stems and leaves (GSLP) by enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE-GSLP) | ||||||||

| 38 | |||||||||

| ] | |||||||||

| 36 | ] | N/A | Man:Rha:Glc:Gal:Xyl:Ara:GlcA:GalA = 1.47:9.63:3.84:15.31:27.94:35.55:3.68:2.586 | [37] | |||||

| Rhizome | A novel polysaccharide (ZOP) was extracted from Zingiber officinale | 6040 kDa (7.17 %) and 5.42 kDa (92.83 %) | GlcA:GalA:Glu:Gal:Ara = 1.97:1.15:94.33:1.48:1.07 | [38] | |||||

| Rhizome | Zingiber officinale polysaccharides (ZOP) | Rhizome | Zingiber officinale polysaccharides 1 (ZOP-1) | 837 kDa | Glc:Gal:Ara = 1.00:95.09:2.26 | ||||

| Anti-influenza effects | 6040 kDa (7.17 %) and 5.42 kDa (92.83 %) | GlcA:GalA:Glc:Gal:Ara = 1.97:1.15:94.33:1.48:1.07 | [ | 38] | |||||

| The mixed polysaccharides (MPs) extracted from shiitake mushroom, poriacocos, gin-ger, and tangerine peel | [ | 35 | ] | [ | Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharides (GP) | 747.2 kDa | Man:Rha:GlcA:GalA:Glc:Gal:Xyl:Ara:Fuc = 0.17:0.13:0.21:0.12:0.08:1:0.16:0.64:0.18 | [29] |

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharides UGP1 | 1002 kDa | N/A | [43] | |||||

| Rhizome | Ginger polysaccharides UGP2 | 1296 kDa | N/A | [43] |

N/A means not mentioned.

4. Biological Activities of Ginger Polysaccharides

Many studies, including in vivo and in vitro experiments, have confirmed that ginger polysaccharides have rich biological activities, including anti-influenza, anti-colitis, anti-tussive, anti-oxidant, and anti-tumor effects. The specific biological activities of ginger polysaccharides are summarized in Table 3.Table 3. Biological activities of ginger polysaccharides and their underlying mechanisms of actions.

| In vivo | |

| 0.342 g/mL, four-week-old female BALB/c mice | Immune mice: The levels of IgG and IgG2a in the serum of mice treated with MPs were higher. |

References

- Garza-Cadena, C.; Ortega-Rivera, D.M.; Machorro-García, G.; Gonzalez-Zermeño, E.M.; Homma-Dueñas, D.; Plata-Gryl, M.; Castro-Muñoz, R. A comprehensive review on Ginger (Zingiber officinale) as a potential source of nutraceuticals for food formulations: Towards the polishing of gingerol and other present biomolecules. Food Chem. 2023, 413, 135629.

- Crichton, M.; Marshall, S.; Marx, W.; Isenring, E.; Lohning, A. Therapeutic health effects of ginger (Zingiber officinale): Updated narrative review exploring the mechanisms of action. Nutr. Rev. 2023, nuac115, Advance online publication.

- Ozkur, M.; Benlier, N.; Takan, I.; Vasileiou, C.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Pavlopoulou, A.; Cetin, Z.; Saygili, E.I. Ginger for Healthy Ageing: A Systematic Review on Current Evidence of Its Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Properties. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 4748447.

- Mahomoodally, M.; Aumeeruddy, M.; Rengasamy, K.R.; Roshan, S.; Hammad, S.; Pandohee, J.; Hu, X.; Zengin, G. Ginger and its active compounds in cancer therapy: From folk uses to nano-therapeutic applications. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 69, 140–149.

- Kiyama, R. Nutritional implications of ginger: Chemistry, biological activities and signaling pathways. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 86, 108486.

- Sowley, E.N.K.; Kankam, F. Harnessing the Therapeutic Properties of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) for the Management of Plant Diseases. In Ginger Cultivation and Its Antimicrobial and Pharmacological Potentials; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020.

- Semwal, R.B.; Semwal, D.K.; Combrinck, S.; Viljoen, A.M. Gingerols and shogaols: Important nutraceutical principles from ginger. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 554–568.

- Unuofin, J.O.; Masuku, N.P.; Paimo, O.K.; Lebelo, S.L. Ginger from Farmyard to Town: Nutritional and Pharmacological Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 779352.

- Bag, B.B. Ginger Processing in India (Zingiber officinale): A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 1639–1651.

- Hasani, H.; Arab, A.; Hadi, A.; Pourmasoumi, M.; Ghavami, A.; Miraghajani, M. Does ginger supplementation lower blood pressure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1639–1647.

- Roudsari, N.M.; Lashgari, N.; Momtaz, S.; Roufogalis, B.; Abdolghaffari, A.H.; Sahebkar, A. Ginger: A complementary approach for management of cardiovascular diseases. Biofactors 2021, 47, 933–951.

- Schepici, G.; Contestabile, V.; Valeri, A.; Mazzon, E. Ginger, a Possible Candidate for the Treatment of Dementias? Molecules 2021, 26, 5700.

- Baliga, M.S.; Haniadka, R.; Pereira, M.M.; D’souza, J.J.; Pallaty, P.L.; Bhat, H.P.; Popuri, S. Update on the Chemopreventive Effects of Ginger and its Phytochemicals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 499–523.

- Dalsasso, R.R.; Valencia, G.A.; Monteiro, A.R. Impact of drying and extractions processes on the recovery of gingerols and shogaols, the main bioactive compounds of ginger. Food Res. Int. 2022, 154, 111043.

- Crichton, M.; Davidson, A.R.; Innerarity, C.; Marx, W.; Lohning, A.; Isenring, E.; Marshall, S. Orally consumed ginger and human health: An umbrella review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1511–1527.

- Lu, F.; Cai, H.; Li, S.; Xie, W.; Sun, R. The Chemical Signatures of Water Extract of Zingiber officinale Rosc. Molecules 2022, 27, 7818.

- Sang, S.; Snook, H.D.; Tareq, F.S.; Fasina, Y. Precision Research on Ginger: The Type of Ginger Matters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 8517–8523.

- Kumar, K.M.; Asish, G.; Sabu, M.; Balachandran, I. Significance of gingers (Zingiberaceae) in Indian System of Medicine–Ayurveda: An overview. Anc. Sci. Life 2013, 32, 253–261.

- Deng, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Sun, X.; Shen, Z.; Dong, J.; Huang, J. Promotion of Mitochondrial Biogenesis via Activation of AMPK-PGC1α Signaling Pathway by Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) Extract, and Its Major Active Component 6-Gingerol. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 2101–2111.

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Luo, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Yao, L.; Shi, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, K. Ginger for health care: An overview of systematic reviews. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 45, 114–123.

- Deng, X.; Chen, D.; Sun, X.; Dong, J.; Huang, J. Effects of ginger extract and its major component 6-gingerol on anti-tumor property through mitochondrial biogenesis in CD8+ T cells. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 3307–3317.

- Baldin, V.P.; de Lima Scodro, R.B.; Fernandez, C.M.M.; Ieque, A.L.; Caleffi-Ferracioli, K.R.; Siqueira, V.L.D.; de Almeida, A.L.; Gonçalves, J.E.; Cortez, D.A.G.; Cardoso, R.F. Ginger essential oil and fractions against Mycobacterium spp. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 244, 112095.

- Camero, M.; Lanave, G.; Catella, C.; Capozza, P.; Gentile, A.; Fracchiolla, G.; Britti, D.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C.; Tempesta, M. Virucidal activity of ginger essential oil against caprine alphaherpesvirus-1. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 230, 150–155.

- Su, P.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Mohan, S.K.; Lu, W. A ginger derivative, zingerone—A phenolic compound—Induces ROS-mediated apoptosis in colon cancer cells (HCT-116). J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2019, 33, e22403.

- Hong, M.-K.; Hu, L.-L.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Xu, Y.-L.; Liu, X.-Y.; He, P.-K.; Jia, Y.-H. 6-Gingerol ameliorates sepsis-induced liver injury through the Nrf2 pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 80, 106196.

- de Lima, R.M.T.; dos Reis, A.C.; de Menezes, A.-A.P.M.; de Oliveira Santos, J.V.; de Oliveira Filho, J.W.G.; de Oliveira Ferreira, J.R.; de Alencar, M.V.O.B.; da Mata, A.M.O.F.; Khan, I.N.; Islam, A.; et al. Protective and therapeutic potential of ginger (Zingiber officinale) extract and -gingerol in cancer: A comprehensive review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1885–1907.

- Ahmed, S.H.H.; Gonda, T.; Hunyadi, A. Medicinal chemistry inspired by ginger: Exploring the chemical space around 6-gingerol. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 26687–26699.

- Mao, Q.-Q.; Xu, X.-Y.; Cao, S.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H.-B. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 2019, 8, 185.

- Hao, W.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Ma, M.; Gao, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wu, X.; Wu, D.; Farag, M.A.; et al. Ginger polysaccharides relieve ulcerative colitis via maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and gut microbiota modulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 219, 730–739.

- Li, W.; Qiu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, L.; Li, Q.; He, Q.; Zheng, Z. Preparation and Characterization of Ginger Peel Polysaccharide–Zn (II) Complexes and Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2331.

- Zagórska, J.; Czernicka-Boś, L.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Iłowiecka, K.; Koch, W. Impact of Thermal Processing on the Selected Biological Activities of Ginger Rhizome—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 412.

- Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, J.; Tang, X.; Li, N. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from ginger. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 862–869.

- Chen, G.-T.; Yuan, B.; Wang, H.-X.; Qi, G.-H.; Cheng, S.-J. Characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides obtained from ginger pomace using two different extraction processes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 801–809.

- Yang, X.; Wei, S.; Lu, X.; Qiao, X.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Capanoglu, E.; Woźniak, Ł.; Zou, L.; Cao, H.; Xiao, J.; et al. A neutral polysaccharide with a triple helix structure from ginger: Characterization and immunomodulatory activity. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129261.

- Bera, K.; Nosalova, G.; Sivova, V.; Ray, B. Structural Elements and Cough Suppressing Activity of Polysaccharides from Zingiber officinale Rhizome. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 105–111.

- Liao, D.-W.; Cheng, C.; Liu, J.-P.; Zhao, L.-Y.; Huang, D.-C.; Chen, G.-T. Characterization and antitumor activities of polysaccharides obtained from ginger (Zingiber officinale) by different extraction methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 894–903.

- Chen, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.; Kan, J. A comparison of a polysaccharide extracted from ginger (Zingiber officinale) stems and leaves using different methods: Preparation, structure characteristics, and biological activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 635–649.

- Jing, Y.; Cheng, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wu, L. Structural Characterization, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of a Novel Polysaccharide from Zingiber officinale and Its Application in Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 917094.

- Zhang, W.; Huang, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Feng, W.; Zheng, D.; Zhao, T.; Mao, G.; Yang, L.; et al. Extraction, purification, characterization and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from Cistanche tubulosa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93 Pt A, 448–458.

- Zeng, P.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L. The structures and biological functions of polysaccharides from traditional Chinese herbs. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 163, 423–444.

- Morris, G.A.; Adams, G.G.; Harding, S.E. On hydrodynamic methods for the analysis of the sizes and shapes of polysaccharides in dilute solution: A short review. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 42, 318–334.

- Das, S.; Nadar, S.S.; Rathod, V.K. Integrated strategies for enzyme assisted extraction of bioactive molecules: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 899–917.

- Liu, J.-P.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.-X.; Huang, D.-C.; Qi, G.-H.; Chen, G.-T. Ginger polysaccharides enhance intestinal immunity by modulating gut microbiota in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 1308–1319.

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Kan, J. Effect of high-pressure ultrasonic extraction on structural characterization and biological activities of polysaccharide from ginger stems and leaves. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 85–101.

- Zhu, H.; Hu, M.; Wang, D.; Xu, G.; Yin, X.; Liu, X.; Ding, M.; Han, L. Mixed polysaccharides derived from Shiitake mushroom, Poriacocos, Ginger, and Tangerine peel enhanced protective immune responses in mice induced by inactivated influenza vaccine. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 126, 110049.

- Yang, D.; Hu, M.; Zhu, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, D.; Ding, M.; Han, L. Mixed polysaccharides derived from shiitake mushroom, Poriacocos, Ginger, and Tangerine peel prevent the H1N1 virus infections in mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 2459–2465.

More