Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Ika Dewi Ana.

Plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (PDENs) comprise various bioactive biomolecules. As an alternative cell-free therapeutic approach, they have the potential to deliver nano-bioactive compounds to the human body, and thus lead to various anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-tumor benefits.

- plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (PDENs)

- biomedical application

- regenerative therapy

1. Introduction

From a biomedical science perspective, a human tissue is a cellular hybrid system between cells and the complete organ [1]. Human tissue is an orchestrated organization composed of cells and their extracellular matrix (ECM) with specific composition and architecture, which carries out a specific function. Functional grouping of multiple tissues forms organs, in which a human body system is organized from an atomic scale, to molecular, macromolecular, organelle, cell, tissue, organ, and up to organ system scales. In the case of an injured, damaged, or missing tissue in the body, constructive remodeling and regenerative therapy are needed to provide engineered ECM with specific structural, mechanical, physical, and chemical properties that closely approximate to the replaced native tissue, which enables the remaining cells to attach, migrate, proliferate, differentiate, and regenerate for structural and functional replacement of the targeted tissue or organ [2,3,4][2][3][4]. This is the fundamental principle of tissue engineering.

In the framework of tissue engineering, the use of stem cells to increase tissue regenerative capacity has attracted scientists, especially mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), due to the fact that their defining properties make them an ideal candidate to cure diseases. Although embryonic and fetal stem cells have the greatest potential to differentiate into different cell types, their application is limited due to ethical and safety issues [5,6[5][6][7][8][9][10],7,8,9,10], as well as the danger of unlimited and uncontrolled cells division [7,8,10,11,12,13,14,15][7][8][10][11][12][13][14][15]. Furthermore, the inherent heterogenicity and variation associated with cell expansion has become a major MSC limit for its clinical applications [16,17,18,19,20][16][17][18][19][20]. In addition, during in vitro cell processing and expansion, changes may occur to MSCs, thereby increasing the risk of MSC therapeutic application. Moreover, the risk of unwanted differentiation in vivo is a problem due to its clinical applications. This leads to alternative cell-free-based therapy with biomolecules secreted from MSCs, which are known as MSC-derived exosomes.

Extensive research has been carried out to identify the molecules involved in paracrine action of stem cells (SCs) for the opening of new therapeutic options in the concept of cell-free-based therapy. At this point, exosomes are nano-sized vesicular particles commonly secreted from eukaryotic cells into the extracellular space, and are intensively investigated as candidate therapeutic agents. These exosomes have known functions in cellular communication [19,20,21[19][20][21][22],22], nutrients [21[21][22],22], bioactive compounds delivery [19[19][20][22],20,22], and cellular immunity [19,20,22][19][20][22]. However, currently, there is no standardized procedure for the isolation, storage, and manufacturing of technology using a quality system for the safety of both donors and recipients in large-scale valorization of MSC-derived exosomes [19]. In the case of manufacturing, for instance, although extensive research has been conducted, the practical use of exosomes is still restricted by the limited exosome secretion capability of cells.

2. Plant-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticle as Biomolecules

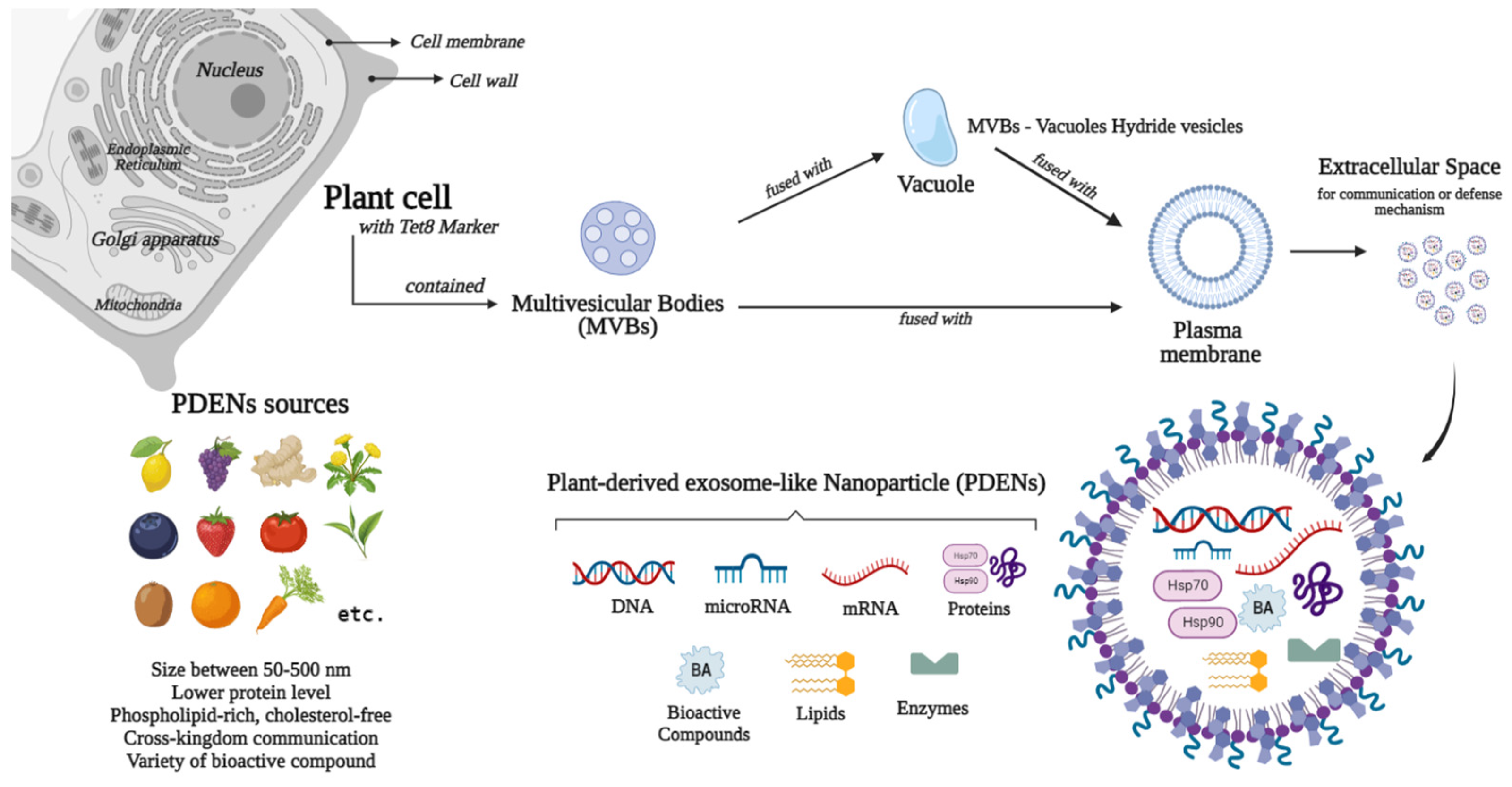

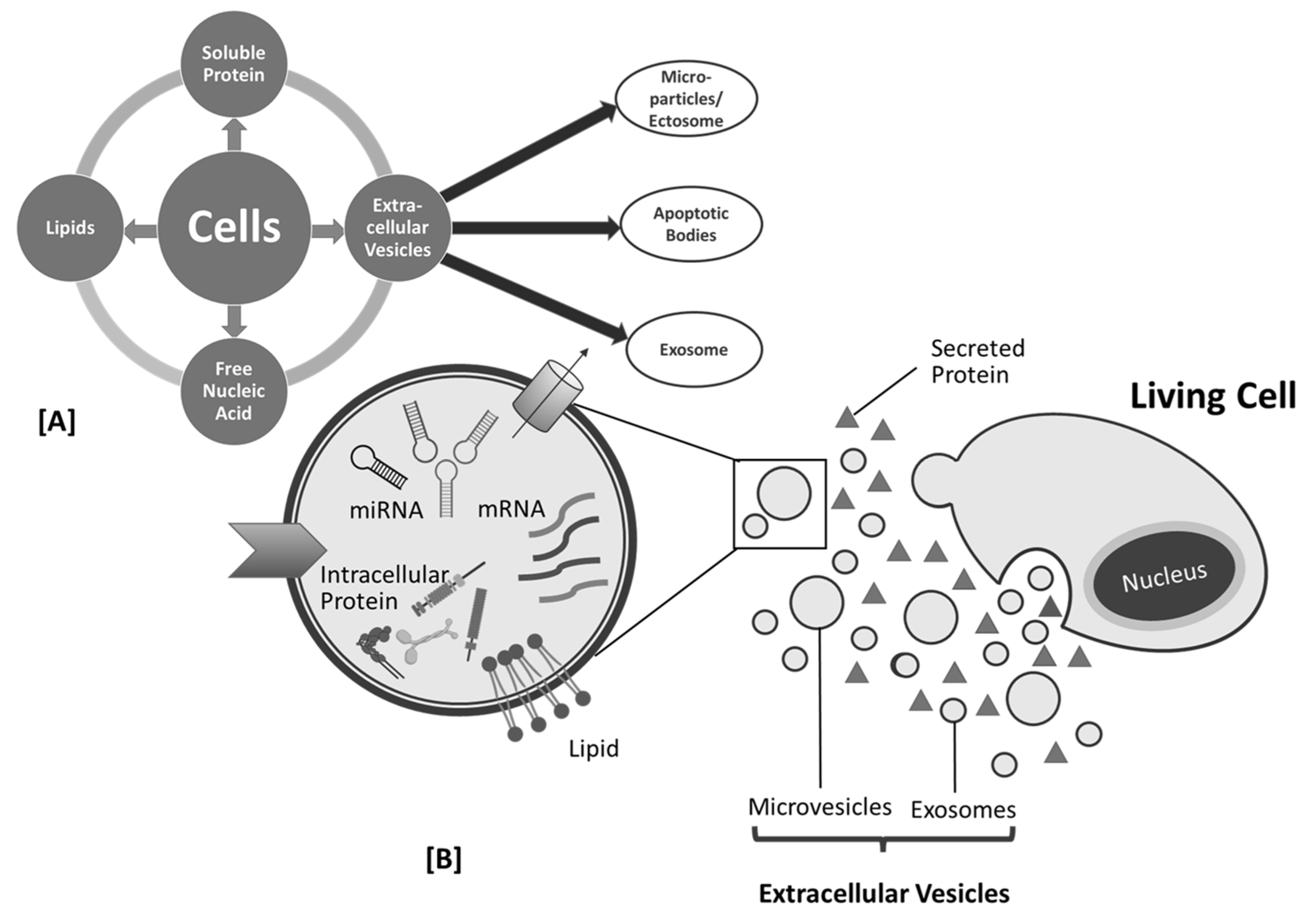

Exosomes were discovered in 1983 by Eberhard Trams and Rose Johnstone [23,24][23][24]. Exosomes are biologically small, nano-sized extracellular vesicles (EVs) with a diameter of 30–150 nm and density of 1.13–1.19 g/mL, secreted naturally by almost all eukaryotic cells [25,26,27,28,29,30,31][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]. Exosomes are important since these vesicles are similar to cargo-containing molecular components, such as DNA, RNA, lipid, and proteins, which are later released into the extracellular matrix as a form of intercellular communication [32,33,34][32][33][34]. Several studies have shown that exosomes comprise cytokines, transcription factor receptors, and other bioactive compounds [35,36][35][36]. The exact mechanism of exosome biogenesis remains controversial; however, they are generally synthesized in the multivesicular endosome compartments of the cell and released when these compartments fuse with the plasma membrane. Therefore, exosomes are also known as membrane-bound or membrane-derived vesicles [26,37,38,39][26][37][38][39]. Formerly, these exosomes were referred to as “ectosomes”, “shed vesicles”, and “small extracellular vesicles (sEVs)”. To date, however, the term “exosome” has received the most popularity [40,41,42][40][41][42]. In comparison to micro vesicles, apoptotic bodies, and oncosomes, exosomes are the smallest type of EVs [32,43,44,45][32][43][44][45]. Research proved EVs, such as exosomes, comprise their own specific cargo. This cargo becomes crucial since it represents the health and/or disease status of the source or parent cells, which has the capacity to alter recipient cells, both neighboring and distantly located ones, by adhering to the cell membrane and releasing its internal cargo. The release of this internal load induces physiological, phenotypic, and functional changes in the recipient cells [26,46,47,48,49,50][26][46][47][48][49][50]. These findings boost numerous investigations into the role of exosomes as novel biomarkers and potential therapeutic agents, which demonstrate that exosomes, as mediators of cell-to-cell communication, are related to physiological and pathological processes on the smallest scale, particularly between cells that occur in the living system [51,52][51][52]. Exosomes are divided into two categories: Natural and engineered exosomes. Natural exosomes are animal derived, mostly from mammals, and originate from cells [53,54,55,56][53][54][55][56] or biofluids [57[57][58][59][60],58,59,60], and plants as natural resources. Figure 1 and Figure 2 describe the biogenesis, sources, and contents of PDEN- and MSC-derived exosomes, whereas engineered exosomes are natural exosomes that have been artificially modified or loaded with therapeutic agents [39]. Animal-derived exosomes are further split into normal and tumor exosomes since exosomes can be produced in both normal and tumor conditions [39]. Studies related to mammalian-derived EVs, including exosomes, are documented in databases, such as Vesiclepedia (http://www.microvesicles.org, accessed on 17 February 2023) and ExoCarta at http://www.exocarta.org, (accessed on 17 February 2023) [61,62,63][61][62][63]. In addition to animals, plants are a source of exosomes, with good development prospects in the future. In recent years, studies have found that nano-sized EVs from plant cells have similar structures to the mammalian exosome [64[64][65][66][67],65,66,67], which is why these EVs are termed as “plant-derived exosome-like nano-particles” with various abbreviations, such as PDELNs [68], PLENs [69], or plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (PDENs) [70]. Other descriptive terms include “plant-derived nanovesicles (PDNVs)” [71], “plant-derived extracellular vesicles (PDEVs)” [72], “plant-derived exosomes” [73], “plant-derived edible nanoparticles” [74], or “edible plant-derived nanovesicles” [75]. The followis reviewng contents uses the term “plant-derived exosome nanoparticles”, which is abbreviated as PDENs.

Figure 1.

Sources, biogenesis, and contents of plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (PDENs).

Figure 2.

Cell products (

A

) and biogenesis of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosome (

B

).

Table 1.

Metabolites found in PDENs from several sources.

| Sources of PDENs | Compounds | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Ginger | 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, 10-gingerol, and 6-shogaol | [88,108][88][108] |

| Grapefruit | Naringenin | [65] |

| Lemon | Citrate, vitamin C, and galacturonic acid-enriched pectin-type polysaccharide | [66,110][66][110] |

| Strawberry | Vitamin C | [88] |

| Tea flower | Epigallo-catechin gallate, epicatechin gallate, epicatechin, vitexin, myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside, kaempferol-3-O-galactoside, and myricetin | [111] |

| Oat | Fiber β-glucan | [112] |

| Broccoli | Sulforaphane | [112] |

References

- Farley, A.; McLafferty, E.; Hendry, C. Cells, Tissues, Organs and Systems. Nurs. Stand. 2012, 26, 40–45.

- Caplan, A.I. Design Parameters For Functional Tissue Engineering. In Functional Tissue Engineering; Guilak, F., Butler, D.L., Goldstein, S.A., Mooney, D.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 1.

- Farach-Carson, M.C.; Wagner, R.C.; Kiick, K.L. Extracellular Matrix: Structure, Function, and Appliations to Tissue Engineering. In Tissue Engineering; Fisher, J.P., Mikos, A.G., Bronzino, J.D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 1–17.

- Badylak, S.; Gilbert, T.; Myers-Irvin, J. The Extracellular Matrix as a Biologic Scaffold for Tissue Engineering. In Tissue Engineering; Bronzino, J., Thomsen, P., Lindahl, A., Hubbel, J., Williams, D., Cancedda, R., de Brujin, J., Sohier, J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 121–143.

- Hare, J.M.; Traverse, J.H.; Henry, T.D.; Dib, N.; Strumpf, R.K.; Schulman, S.P.; Gerstenblith, G.; DeMaria, A.N.; Denktas, A.E.; Gammon, R.S.; et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Escalation Study of Intravenous Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (Prochymal) After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 2277–2286.

- Beyth, S.; Schroeder, J.; Liebergall, M. Stem Cells in Bone Diseases: Current Clinical Practice. Br. Med. Bull. 2011, 99, 199–210.

- Casteilla, L.; Planat-Benard, V.; Laharrague, P.; Cousin, B. Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells: Their Identity and Uses in Clinical Trials, an Update. World. J. Stem. Cells 2011, 3, 25–33.

- Mingliang, R.; Bo, Z.; Zhengguo, W. Stem Cells for Cardiac Repair: Status, Mechanisms, and New Strategies. Stem. Cells Int. 2011, 2011, 310928.

- Yokoo, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Yokote, S. Potential Use of Stem Cells for Kidney Regeneration. Int. J. Nephrol. 2011, 2011, 591731.

- Zakrzewski, W.; Dobrzyński, M.; Szymonowicz, M.; Rybak, Z. Stem Cells: Past, Present, and Future. Stem. Cell Res. 2019, 10, 68.

- Kunter, U.; Rong, S.; Boor, P.; Eitner, F.; Müller-Newen, G.; Djuric, Z.; van Roeyen, C.R.; Konieczny, A.; Ostendorf, T.; Villa, L.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Prevent Progressive Experimental Renal Failure but Maldifferentiate into Glomerular Adipocytes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 1754–1764.

- Michalopoulos, G.K. Liver Regeneration. J. Cell Physiol. 2007, 213, 286–300.

- Rubina, K.; Kalinina, N.; Efimenko, A.; Lopatina, T.; Melikhova, V.; Tsokolaeva, Z.; Sysoeva, V.; Tkachuk, V.; Parfyonova, Y. Adipose Stromal Cells Stimulate Angiogenesis via Promoting Progenitor Cell Differentiation, Secretion of Angiogenic Factors, and Enhancing Vessel Maturation. Tissue. Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 2039–2048.

- Tögel, F.E.; Westenfelder, C. The Role of Multipotent Marrow Stromal Cells (MSCs) in Tissue Regeneration. Organogenesis 2011, 7, 96–100.

- Mahanani, E.S.; Bachtiar, I.; Ana, I.D. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Behavior on Synthetic Coral Scaffold. Key. Eng. Mater. 2016, 696, 205–211.

- Breitbach, M.; Bostani, T.; Roell, W.; Xia, Y.; Dewald, O.; Nygren, J.M.; Fries, J.W.U.; Tiemann, K.; Bohlen, H.; Hescheler, J.; et al. Potential Risks of Bone Marrow Cell Transplantation into Infarcted Hearts. Blood 2007, 110, 1362–1369.

- Wang, J.J.; Ye, F.; Cheng, L.J.; Shi, Y.J.; Bao, J.; Sun, H.Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Bu, H. Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promoted by Overexpression of Connective Tissue Growth Factor. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2009, 10, 355–367.

- Gomzikova, M.O.; Rizvanov, A.A. Current Trends in Regenerative Medicine: From Cell to Cell-Free Therapy. Bionanoscience 2017, 7, 240–245.

- Ana, I.D.; Barlian, A.; Hidajah, A.C.; Wijaya, C.H.; Notobroto, H.B.; Kencana Wungu, T.D. Challenges and Strategy in Treatment with Exosomes for Cell-Free-Based Tissue Engineering in Dentistry. Future Sci. OA 2021, 7, 1–21.

- Amsar, R.M.; Wijaya, C.H.; Ana, I.D.; Hidajah, A.C.; Notobroto, H.B.; Kencana Wungu, T.D.; Barlian, A. Extracellular Vesicles: A Promising Cell-Free Therapy for Cartilage Repair. Future Sci. OA 2022, 8, FSO774.

- Suharta, S.; Barlian, A.; Hidajah, A.C.; Notobroto, H.B.; Ana, I.D.; Indariani, S.; Wungu, T.D.K.; Wijaya, C.H. Plant-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles: A Concise Review on Its Extraction Methods, Content, Bioactivities, and Potential as Functional Food Ingredient. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2838–2850.

- Ratnadewi, D.; Widjaja, C.H.; Barlian, A.; Amsar, R.M.; Ana, I.D.; Hidajah, A.C.; Notobroto, H.B.; Wungu, T.D.K. Isolation of Native Plant-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles and Their Uptake by Human Cells. Hayati 2023, 30, 182–192.

- Trams, E.G.; Lauter, C.J.; Salem, N.J.; Heine, U. Exfoliation of Membrane Ecto-Enzymes in the Form of Micro-Vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1981, 645, 63–70.

- Johnstone, R.M. Revisiting the Road to the Discovery of Exosomes. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2005, 34, 214–219.

- Théry, C.; Zitvogel, L.; Amigorena, S. Exosomes: Composition, Biogenesis and Function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 569–579.

- Théry, C. Exosomes: Secreted Vesicles and Intercellular Communications. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2011, 3, 1–8.

- el Andaloussi, S.; Mäger, I.; Breakefield, X.O.; Wood, M.J.A. Extracellular Vesicles: Biology and Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 347–357.

- Lötvall, J.; Hill, A.F.; Hochberg, F.; Buzás, E.I.; di Vizio, D.; Gardiner, C.; Gho, Y.S.; Kurochkin, I.; Mathivanan, S.; Quesenberry, P.; et al. Minimal Experimental Requirements for Definition of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Functions: A Position Statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 26913.

- Cocucci, E.; Meldolesi, J. Ectosomes and Exosomes: Shedding the Confusion between Extracellular Vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 364–372.

- Pluchino, S.; Smith, J.A. Explicating Exosomes: Reclassifying the Rising Stars of Intercellular Communication. Cell 2019, 177, 225–227.

- Weaver, J.W.; Zhang, J.; Rojas, J.; Musich, P.R.; Yao, Z.; Jiang, Y. The Application of Exosomes in the Treatment of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1022725.

- Zaborowski, M.P.; Balaj, L.; Breakefield, X.O.; Lai, C.P. Extracellular Vesicles: Composition, Biological Relevance, and Methods of Study. Bioscience 2015, 65, 783–797.

- Lopez-Verrilli, M.A.; Caviedes, A.; Cabrera, A.; Sandoval, S.; Wyneken, U.; Khoury, M. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes from Different Sources Selectively Promote Neuritic Outgrowth. Neurosci 2016, 320, 129–139.

- Willms, E.; Johansson, H.J.; Mäger, I.; Lee, Y.; Blomberg, K.E.M.; Sadik, M.; Alaarg, A.; Smith, C.I.E.; Lehtiö, J.; el Andaloussi, S.; et al. Cells Release Subpopulations of Exosomes with Distinct Molecular and Biological Properties. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22519.

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445.e18.

- Yang, X.-X.; Sun, C.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.-L. New Insight into Isolation, Identification Techniques and Medical Applications of Exosomes. J. Control. Release 2019, 308, 119–129.

- Harry Heijnen, B.F.; Schiel, A.E.; Fijnheer, R.; Geuze, H.J.; Sixma, J.J. Activated Platelets Release Two Types of Membrane Vesicles: Microvesicles by Surface Shedding and Exosomes Derived From Exocytosis of Multivesicular Bodies and-Granules. Blood 1999, 94, 3791–3799.

- Stremersch, S.; de Smedt, S.C.; Raemdonck, K. Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications of Extracellular Vesicles. JCR 2016, 244, 167–183.

- Zhang, Y.; Bi, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; Du, S.; Li, P. Exosome: A Review of Its Classification, Isolation Techniques, Storage, Diagnostic and Targeted Therapy Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6917–6934.

- Cassarà, D.; Ginestra, A.; Dolo, V.; Miele, M.; Caruso, G.; Lucania, G.; Vittorelli, M.L. Modulation of Vesicle Shedding in 8701 BC Human Breast Carcinoma Cells. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. Pathol. 1998, 30, 45–53.

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A Position Statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and Update of the MISEV2014 Guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750.

- Stein, J.M.; Luzio, J.P. Ectocytosis Caused by Sublytic Autologous Complement Attack on Human Neutrophils. The Sorting of Endogenous Plasma-Membrane Proteins and Lipids into Shed Vesicles. Biochem. J. 1991, 274 Pt 2, 381–386.

- Marote, A.; Teixeira, F.G.; Mendes-Pinheiro, B.; Salgado, A.J. MSCs-Derived Exosomes: Cell-Secreted Nanovesicles with Regenerative Potential. Front. Pharm. 2016, 7, 231.

- McGough, I.J.; Vincent, J.-P. Exosomes in Developmental Signalling. Development 2016, 143, 2482–2493.

- Whiteside, T.L. Exosomes and Tumor-Mediated Immune Suppression. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1216–1223.

- Schorey, J.S.; Bhatnagar, S. Exosome Function: From Tumor Immunology to Pathogen Biology. Traffic 2008, 9, 871–881.

- Bang, C.; Thum, T. Exosomes: New Players in Cell-Cell Communication. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 2060–2064.

- Eitan, E.; Suire, C.; Zhang, S.; Mattson, M.P. Impact of Lysosome Status on Extracellular Vesicle Content and Release. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 65–74.

- Kalluri, R. The Biology and Function of Exosomes in Cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1208–1215.

- Sarko, D.K.; McKinney, C.E. Exosomes: Origins and Therapeutic Potential for Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 82.

- Properzi, F.; Logozzi, M.; Fais, S. Exosomes: The Future of Biomarkers in Medicine. Biomark. Med. 2013, 7, 769–778.

- Lin, J.; Li, J.; Huang, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.-M.; Xu, Y.-M.; Huang, L.-F.; Wang, X.-Z. Exosomes: Novel Biomarkers for Clinical Diagnosis. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 657086.

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, K.; Wu, S.; Cui, M.; Xu, T. Focus on Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Opportunities and Challenges in Cell-Free Therapy. Stem. Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 6305295.

- He, C.; Hua, W.; Liu, J.; Fan, L.; Hua, W.; Sun, G. Exosomes Derived from Endoplasmic Reticulum-Stressed Liver Cancer Cells Enhance the Expression of Cytokines in Macrophages via the STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 589–600.

- Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Jin, X.; Hu, D.; Xia, C.; Xu, H.; Hu, J. NK Cell-Derived Exosomes Carry MiR-207 and Alleviate Depression-like Symptoms in Mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 126.

- Zhao, D.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Han, D. GelMA Combined with Sustained Release of HUVECs Derived Exosomes for Promoting Cutaneous Wound Healing and Facilitating Skin Regeneration. J. Mol. Histol. 2020, 51, 251–263.

- Agrawal, A.K.; Aqil, F.; Jeyabalan, J.; Spencer, W.A.; Beck, J.; Gachuki, B.W.; Alhakeem, S.S.; Oben, K.; Munagala, R.; Bondada, S.; et al. Milk-Derived Exosomes for Oral Delivery of Paclitaxel. Nanomedicine 2017, 13, 1627–1636.

- Srivastava, A.; Moxley, K.; Ruskin, R.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Zhao, Y.D.; Ramesh, R. A Non-Invasive Liquid Biopsy Screening of Urine-Derived Exosomes for MiRNAs as Biomarkers in Endometrial Cancer Patients. AAPS J. 2018, 20, 82.

- Shaimardanova, A.A.; Solovyeva, V.V.; Chulpanova, D.S.; James, V.; Kitaeva, K.V.; Rizvanov, A.A. Extracellular Vesicles in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Central Nervous System Diseases. Neural. Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 586–596.

- Zhuo, C.J.; Hou, W.H.; Jiang, D.G.; Tian, H.J.; Wang, L.N.; Jia, F.; Zhou, C.H.; Zhu, J.J. Circular RNAs in Early Brain Development and Their Influence and Clinical Significance in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Neural. Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 817–823.

- Kalra, H.; Simpson, R.J.; Ji, H.; Aikawa, E.; Altevogt, P.; Askenase, P.; Bond, V.C.; Borràs, F.E.; Breakefield, X.; Budnik, V.; et al. Vesiclepedia: A Compendium for Extracellular Vesicles with Continuous Community Annotation. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001450.

- Keerthikumar, S.; Chisanga, D.; Ariyaratne, D.; al Saffar, H.; Anand, S.; Zhao, K.; Samuel, M.; Pathan, M.; Jois, M.; Chilamkurti, N.; et al. ExoCarta: A Web-Based Compendium of Exosomal Cargo. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 688–692.

- Pathan, M.; Fonseka, P.; Chitti, S.; Kang, T.; Sanwlani, R.; van Deun, J.; Hendrix, A.; Mathivanan, S. Vesiclepedia 2019: A Compendium of RNA, Proteins, Lipids and Metabolites in Extracellular Vesicles. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2019, 47, D516–D519.

- Regente, M.; Corti-Monzón, G.; Maldonado, A.M.; Pinedo, M.; Jorrín, J.; de la Canal, L. Vesicular Fractions of Sunflower Apoplastic Fluids Are Associated with Potential Exosome Marker Proteins. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 3363–3366.

- Wang, B.; Zhuang, X.; Deng, Z.-B.; Jiang, H.; Mu, J.; Wang, Q.; Xiang, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, L.; Dryden, G.; et al. Targeted Drug Delivery to Intestinal Macrophages by Bioactive Nanovesicles Released from Grapefruit. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 522–534.

- Baldini, N.; Torreggiani, E.; Roncuzzi, L.; Perut, F.; Zini, N.; Avnet, S. Exosome-like Nanovesicles Isolated from Citrus Limon L. Exert Antioxidative Effect. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2018, 19, 877–885.

- Akuma, P.; Okagu, O.D.; Udenigwe, C.C. Naturally Occurring Exosome Vesicles as Potential Delivery Vehicle for Bioactive Compounds. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 23.

- Li, D.; Yao, X.; Yue, J.; Fang, Y.; Cao, G.; Midgley, A.C.; Nishinari, K.; Yang, Y. Advances in Bioactivity of MicroRNAs of Plant-Derived Exosome-Like Nanoparticles and Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6285–6299.

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, G.; Zeng, L.; Xu, S.; Cheng, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Chen, J.; Pathak, J.L.; Wu, L.; et al. The Emerging Role of Plant-Derived Exosomes-Like Nanoparticles in Immune Regulation and Periodontitis Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 896745.

- Chen, N.; Sun, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cribbs, A.P.; Xiao, B. Edible Plant-Derived Nanotherapeutics and Nanocarriers: Recent Progress and Future Directions. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2022, 19, 409–419.

- Logozzi, M.; di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Fais, S. The Potentiality of Plant-Derived Nanovesicles in Human Health-A Comparison with Human Exosomes and Artificial Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4919.

- Karamanidou, T.; Tsouknidas, A. Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Therapeutic Nanocarriers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 191.

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, R. Plant-Derived Exosomes as a Drug-Delivery Approach for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colitis-Associated Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 822.

- Zhang, M.; Viennois, E.; Xu, C.; Merlin, D. Plant Derived Edible Nanoparticles as a New Therapeutic Approach against Diseases. Tissue Barriers 2016, 4, e1134415.

- Kim, S.Q.; Kim, K.-H. Emergence of Edible Plant-Derived Nanovesicles as Functional Food Components and Nanocarriers for Therapeutics Delivery: Potentials in Human Health and Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 2232.

- Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Stierhof, Y.-D.; Robinson, D.G.; Jiang, L. Unconventional Protein Secretion. Trends. Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 606–615.

- Regente, M.; Pinedo, M.; Elizalde, M.; de la Canal, L. Apoplastic Exosome-like Vesicles: A New Way of Protein Secretion in Plants? Plant Signal Behav. 2012, 7, 544–546.

- Canitano, A.; Venturi, G.; Borghi, M.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Fais, S. Exosomes Released in Vitro from Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-Infected Cells Contain EBV-Encoded Latent Phase MRNAs. Cancer Lett. 2013, 337, 193–199.

- Cossetti, C.; Lugini, L.; Astrologo, L.; Saggio, I.; Fais, S.; Spadafora, C. Soma-to-Germline Transmission of RNA in Mice Xenografted with Human Tumour Cells: Possible Transport by Exosomes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101629.

- Federici, C.; Petrucci, F.; Caimi, S.; Cesolini, A.; Logozzi, M.; Borghi, M.; D’Ilio, S.; Lugini, L.; Violante, N.; Azzarito, T.; et al. Exosome Release and Low PH Belong to a Framework of Resistance of Human Melanoma Cells to Cisplatin. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88193.

- Properzi, F.; Logozzi, M.; Abdel-Haq, H.; Federici, C.; Lugini, L.; Azzarito, T.; Cristofaro, I.; Sevo, D.; Ferroni, E.; Cardone, F.; et al. Detection of Exosomal Prions in Blood by Immunochemistry Techniques. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 1969–1974.

- Lugini, L.; Valtieri, M.; Federici, C.; Cecchetti, S.; Meschini, S.; Condello, M.; Signore, M.; Fais, S. Exosomes from Human Colorectal Cancer Induce a Tumor-like Behavior in Colonic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 50086–50098.

- Iessi, E.; Logozzi, M.; Lugini, L.; Azzarito, T.; Federici, C.; Spugnini, E.P.; Mizzoni, D.; di Raimo, R.; Angelini, D.F.; Battistini, L.; et al. Acridine Orange/Exosomes Increase the Delivery and the Effectiveness of Acridine Orange in Human Melanoma Cells: A New Prototype for Theranostics of Tumors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 648–657.

- Logozzi, M.; Mizzoni, D.; Bocca, B.; di Raimo, R.; Petrucci, F.; Caimi, S.; Alimonti, A.; Falchi, M.; Cappello, F.; Campanella, C.; et al. Human Primary Macrophages Scavenge AuNPs and Eliminate It through Exosomes. A Natural Shuttling for Nanomaterials. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 137, 23–36.

- Pérez-Bermúdez, P.; Blesa, J.; Soriano, J.M.; Marcilla, A. Extracellular Vesicles in Food: Experimental Evidence of Their Secretion in Grape Fruits. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 98, 40–50.

- Nemati, M.; Singh, B.; Mir, R.A.; Nemati, M.; Babaei, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Rasmi, Y.; Golezani, A.G.; Rezaie, J. Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Novel Nanomedicine Approach with Advantages and Challenges. Cell Commun. Signal 2022, 20, 69.

- Crescitelli, R.; Lässer, C.; Jang, S.C.; Cvjetkovic, A.; Malmhäll, C.; Karimi, N.; Höög, J.L.; Johansson, I.; Fuchs, J.; Thorsell, A.; et al. Subpopulations of Extracellular Vesicles from Human Metastatic Melanoma Tissue Identified by Quantitative Proteomics after Optimized Isolation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1722433.

- Perut, F.; Roncuzzi, L.; Avnet, S.; Massa, A.; Zini, N.; Sabbadini, S.; Giampieri, F.; Mezzetti, B.; Baldini, N. Strawberry-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles Prevent Oxidative Stress in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 87.

- Zhang, M.; Viennois, E.; Prasad, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Han, M.K.; Xiao, B.; Xu, C.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. Edible Ginger-Derived Nanoparticles: A Novel Therapeutic Approach for the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colitis-Associated Cancer. Biomaterials 2016, 101, 321–340.

- Jimenez-Jimenez, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Santana, O.; Aguirre, J.; Kuchitsu, K.; Cárdenas, L. Emerging Roles of Tetraspanins in Plant Inter-Cellular and Inter-Kingdom Communication. Plant Signal Behav. 2019, 14, 1581559.

- Dad, H.A.; Gu, T.W.; Zhu, A.Q.; Huang, L.Q.; Peng, L.H. Plant Exosome-like Nanovesicles: Emerging Therapeutics and Drug Delivery Nanoplatforms. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 13–31.

- Özkan, İ.; Koçak, P.; Yıldırım, M.; Ünsal, N.; Yılmaz, H.; Telci, D.; Şahin, F. Garlic (Allium Sativum)-Derived SEVs Inhibit Cancer Cell Proliferation and Induce Caspase Mediated Apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14773.

- Savcı, Y.; Kırbaş, O.K.; Bozkurt, B.T.; Abdik, E.A.; Taşlı, P.N.; Şahin, F.; Abdik, H. Grapefruit-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as a Promising Cell-Free Therapeutic Tool for Wound Healing. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 5144–5156.

- Pocsfalvi, G.; Turiák, L.; Ambrosone, A.; del Gaudio, P.; Puska, G.; Fiume, I.; Silvestre, T.; Vékey, K. Protein Biocargo of Citrus Fruit-Derived Vesicles Reveals Heterogeneous Transport and Extracellular Vesicle Populations. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 229, 111–121.

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J. Exosome-like Nanoparticles from Ginger Rhizomes Inhibited NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 2690–2699.

- Sarvarian, P.; Samadi, P.; Gholipour, E.; Shams Asenjan, K.; Hojjat-Farsangi, M.; Motavalli, R.; Motavalli Khiavi, F.; Yousefi, M. Application of Emerging Plant-Derived Nanoparticles as a Novel Approach for Nano-Drug Delivery Systems. Immunol. Investig. 2022, 51, 1039–1059.

- Ju, S.; Mu, J.; Dokland, T.; Zhuang, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Xiang, X.; Deng, Z.-B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; et al. Grape Exosome-like Nanoparticles Induce Intestinal Stem Cells and Protect Mice from DSS-Induced Colitis. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1345–1357.

- Liu, C.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Tu, K.; Zhang, M. Oral Administration of Turmeric-Derived Exosome-like Nanovesicles with Anti-Inflammatory and pro-Resolving Bioactions for Murine Colitis Therapy. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 206.

- Berger, E.; Colosetti, P.; Jalabert, A.; Meugnier, E.; Wiklander, O.P.B.; Jouhet, J.; Errazurig-Cerda, E.; Chanon, S.; Gupta, D.; Rautureau, G.J.P.; et al. Use of Nanovesicles from Orange Juice to Reverse Diet-Induced Gut Modifications in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 18, 880–892.

- Wang, Q.; Zhuang, X.; Mu, J.; Deng, Z.-B.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, X.; Wang, B.; Yan, J.; Miller, D.; et al. Delivery of Therapeutic Agents by Nanoparticles Made of Grapefruit-Derived Lipids. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1867.

- Teng, Y.; Ren, Y.; Sayed, M.; Hu, X.; Lei, C.; Kumar, A.; Hutchins, E.; Mu, J.; Deng, Z.; Luo, C.; et al. Plant-Derived Exosomal MicroRNAs Shape the Gut Microbiota. Cell Host. Microbe. 2018, 24, 637–652.e8.

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Guo, C.; Yao, J.; Mi, S. Exosome and Exosomal MicroRNA: Trafficking, Sorting, and Function. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 17–24.

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402.

- Correia de Sousa, M.; Gjorgjieva, M.; Dolicka, D.; Sobolewski, C.; Foti, M. Deciphering MiRNAs’ Action through MiRNA Editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6249.

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Liao, H.; Fu, H.; Yang, X.; Xiang, Q.; Zhang, S. Plant Exosome-like Nanoparticles as Biological Shuttles for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 104.

- He, B.; Cai, Q.; Qiao, L.; Huang, C.-Y.; Wang, S.; Miao, W.; Ha, T.; Wang, Y.; Jin, H. RNA-Binding Proteins Contribute to Small RNA Loading in Plant Extracellular Vesicles. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 342–352.

- Liu, G.; Kang, G.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Cai, Q. Extracellular Vesicles: Emerging Players in Plant Defense Against Pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 757925.

- Stotz, H.U.; Brotherton, D.; Inal, J. Communication Is Key: Extracellular Vesicles as Mediators of Infection and Defence during Host-Microbe Interactions in Animals and Plants. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 46, fuab044.

- Stanly, C.; Alfieri, M.; Ambrosone, A.; Leone, A.; Fiume, I.; Pocsfalvi, G. Grapefruit-Derived Micro and Nanovesicles Show Distinct Metabolome Profiles and Anticancer Activities in the A375 Human Melanoma Cell Line. Cells 2020, 9, 722.

- Lei, C.; Teng, Y.; He, L.; Sayed, M.; Mu, J.; Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Kumar, A.; Sundaram, K.; Sriwastva, M.K.; et al. Lemon Exosome-like Nanoparticles Enhance Stress Survival of Gut Bacteria by RNase P-Mediated Specific TRNA Decay. iScience. 2021, 24, 102511.

- Chen, Q.; Li, Q.; Liang, Y.; Zu, M.; Chen, N.; Canup, B.S.B.; Luo, L.; Wang, C.; Zeng, L.; Xiao, B. Natural Exosome-like Nanovesicles from Edible Tea Flowers Suppress Metastatic Breast Cancer via ROS Generation and Microbiota Modulation. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 907–923.

- Man, F.; Meng, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, J.; Lu, R. The Study of Ginger-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as a Natural Nanoscale Drug Carrier and Their Intestinal Absorption in Rats. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2021, 22, 206.

- Zhuang, X.; Deng, Z.-B.; Mu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Miller, D.; Feng, W.; McClain, C.J.; Zhang, H.-G. Ginger-Derived Nanoparticles Protect against Alcohol-Induced Liver Damage. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 28713.

- Hadizadeh, N.; Bagheri, D.; Shamsara, M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Farmany, A.; Xu, M.; Liang, Z.; Razi, F.; Hashemi, E. Extracellular Vesicles Biogenesis, Isolation, Manipulation and Genetic Engineering for Potential in Vitro and in Vivo Therapeutics: An Overview. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1019821.

- Li, P.; Kaslan, M.; Lee, S.H.; Yao, J.; Gao, Z. Progress in Exosome Isolation Techniques. Theranostics 2017, 7, 789–804.

- Bosque, A.; Dietz, L.; Gallego-Lleyda, A.; Sanclemente, M.; Iturralde, M.; Naval, J.; Alava, M.A.; Martínez-Lostao, L.; Thierse, H.-J.; Anel, A. Comparative Proteomics of Exosomes Secreted by Tumoral Jurkat T Cells and Normal Human T Cell Blasts Unravels a Potential Tumorigenic Role for Valosin-Containing Protein. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 29287–29305.

- Sidhom, K.; Obi, P.O.; Saleem, A. A Review of Exosomal Isolation Methods: Is Size Exclusion Chromatography the Best Option? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 466.

- Livshts, M.A.; Khomyakova, E.; Evtushenko, E.G.; Lazarev, V.N.; Kulemin, N.A.; Semina, S.E.; Generozov, E.v.; Govorun, V.M. Isolation of Exosomes by Differential Centrifugation: Theoretical Analysis of a Commonly Used Protocol. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17319.

- Subudhi, P.D.; Bihari, C.; Sarin, S.K.; Baweja, S. Emerging Role of Edible Exosomes-Like Nanoparticles (ELNs) as Hepatoprotective Agents. Nanotheranostics 2022, 6, 365–375.

- Linares, R.; Tan, S.; Gounou, C.; Arraud, N.; Brisson, A.R. High-Speed Centrifugation Induces Aggregation of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 29509.

- Street, J.M.; Barran, P.E.; Mackay, C.L.; Weidt, S.; Balmforth, C.; Walsh, T.S.; Chalmers, R.T.A.; Webb, D.J.; Dear, J.W. Identification and Proteomic Profiling of Exosomes in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 5.

- Szatanek, R.; Baran, J.; Siedlar, M.; Baj-Krzyworzeka, M. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles: Determining the Correct Approach (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 11–17.

- Yu, L.L.; Zhu, J.; Liu, J.X.; Jiang, F.; Ni, W.K.; Qu, L.S.; Ni, R.Z.; Lu, C.H.; Xiao, M.B. A Comparison of Traditional and Novel Methods for the Separation of Exosomes from Human Samples. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3634563.

- Ebert, B.; Rai, A.J. Isolation and Characterization of Amniotic Fluid-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Biomarker Discovery. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press Inc.: Totova, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 1885, pp. 287–294.

- Alexander, R.P.; Chiou, N.-T.; Ansel, K.M. Improved Exosome Isolation by Sucrose Gradient Fractionation of Ultracentrifuged Crude Exosome Pellets. Protoc. Exch. 2016, 1–4.

- Tauro, B.J.; Greening, D.W.; Mathias, R.A.; Ji, H.; Mathivanan, S.; Scott, A.M.; Simpson, R.J. Comparison of Ultracentrifugation, Density Gradient Separation, and Immunoaffinity Capture Methods for Isolating Human Colon Cancer Cell Line LIM1863-Derived Exosomes. Methods 2012, 56, 293–304.

- Lobb, R.J.; Becker, M.; Wen, S.W.; Wong, C.S.F.; Wiegmans, A.P.; Leimgruber, A.; Möller, A. Optimized Exosome Isolation Protocol for Cell Culture Supernatant and Human Plasma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27031.

- Konoshenko, M.Y.; Lekchnov, E.A.; Vlassov, A.v.; Laktionov, P.P. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles: General Methodologies and Latest Trends. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8545347.

- van Deun, J.; Mestdagh, P.; Agostinis, P.; Akay, Ö.; Anand, S.; Anckaert, J.; Martinez, Z.A.; Baetens, T.; Beghein, E.; Bertier, L.; et al. EV-TRACK: Transparent Reporting and Centralizing Knowledge in Extracellular Vesicle Research. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 228–232.

- Zhao, L.; Gu, C.; Gan, Y.; Shao, L.; Chen, H.; Zhu, H. Exosome-Mediated SiRNA Delivery to Suppress Postoperative Breast Cancer Metastasis. J. Control. Release 2020, 318, 1–15.

- Vergauwen, G.; Dhondt, B.; van Deun, J.; de Smedt, E.; Berx, G.; Timmerman, E.; Gevaert, K.; Miinalainen, I.; Cocquyt, V.; Braems, G.; et al. Confounding Factors of Ultrafiltration and Protein Analysis in Extracellular Vesicle Research. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2704.

- Böing, A.N.; van der Pol, E.; Grootemaat, A.E.; Coumans, F.A.W.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Single-Step Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles by Size-Exclusion Chromatography. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 23430.

- Gámez-Valero, A.; Monguió-Tortajada, M.; Carreras-Planella, L.; Franquesa, M.; Beyer, K.; Borràs, F.E. Size-Exclusion Chromatography-Based Isolation Minimally Alters Extracellular Vesicles’ Characteristics Compared to Precipitating Agents. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33641.

- Chen, Q.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Exosomes as Novel Delivery Systems for Application in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Molecules 2022, 27, 7789.

- Gercel-Taylor, C.; Atay, S.; Tullis, R.H.; Kesimer, M.; Taylor, D.D. Nanoparticle Analysis of Circulating Cell-Derived Vesicles in Ovarian Cancer Patients. Anal. Biochem. 2012, 428, 44–53.

- Zhang, H.; Lyden, D. Asymmetric-Flow Field-Flow Fractionation Technology for Exomere and Small Extracellular Vesicle Separation and Characterization. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 1027–1053.

- Lewis, G.D.; Metcalf, T.G. Polyethylene Glycol Precipitation for Recovery of Pathogenic Viruses, Including Hepatitis A Virus and Human Rotavirus, from Oyster, Water, and Sediment Samples. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 1983–1988.

- Yamamoto, K.R.; Alberts, B.M.; Benzinger, R.; Lawhorne, L.; Treiber, G. Rapid Bacteriophage Sedimentation in the Presence of Polyethylene Glycol and Its Application to Large-Scale Virus Purification. Virology 1970, 40, 734–744.

- Oh, D.K.; Hyun, C.K.; Kim, J.H.; Park, Y.H. Production of Penicillin in a Fluidized-Bed Bioreactor: Control of Cell Growth and Penicillin Production by Phosphate Limitation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1988, 32, 569–573.

- Tian, J.; Casella, G.; Zhang, Y.; Rostami, A.; Li, X. Potential Roles of Extracellular Vesicles in the Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 620–632.

- Rider, M.A.; Hurwitz, S.N.; Meckes, D.G. ExtraPEG: A Polyethylene Glycol-Based Method for Enrichment of Extracellular Vesicles. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23978.

- Kalarikkal, S.P.; Prasad, D.; Kasiappan, R.; Chaudhari, S.R.; Sundaram, G.M. A Cost-Effective Polyethylene Glycol-Based Method for the Isolation of Functional Edible Nanoparticles from Ginger Rhizomes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4456.

- Zarovni, N.; Corrado, A.; Guazzi, P.; Zocco, D.; Lari, E.; Radano, G.; Muhhina, J.; Fondelli, C.; Gavrilova, J.; Chiesi, A. Integrated Isolation and Quantitative Analysis of Exosome Shuttled Proteins and Nucleic Acids Using Immunocapture Approaches. Methods 2015, 87, 46–58.

- Koliha, N.; Wiencek, Y.; Heider, U.; Jüngst, C.; Kladt, N.; Krauthäuser, S.; Johnston, I.C.D.; Bosio, A.; Schauss, A.; Wild, S. A Novel Multiplex Bead-Based Platform Highlights the Diversity of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2016, 5, 29975.

- Boriachek, K.; Masud, M.K.; Palma, C.; Phan, H.P.; Yamauchi, Y.; Hossain, M.S.A.; Nguyen, N.T.; Salomon, C.; Shiddiky, M.J.A. Avoiding Pre-Isolation Step in Exosome Analysis: Direct Isolation and Sensitive Detection of Exosomes Using Gold-Loaded Nanoporous Ferric Oxide Nanozymes. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 3827–3834.

- Ghosh, A.; Davey, M.; Chute, I.C.; Griffiths, S.G.; Lewis, S.; Chacko, S.; Barnett, D.; Crapoulet, N.; Fournier, S.; Joy, A.; et al. Rapid Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles from Cell Culture and Biological Fluids Using a Synthetic Peptide with Specific Affinity for Heat Shock Proteins. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 110443.

- Balaj, L.; Atai, N.A.; Chen, W.; Mu, D.; Tannous, B.A.; Breakefield, X.O.; Skog, J.; Maguire, C.A. Heparin Affinity Purification of Extracellular Vesicles. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10266.

- Zhou, Y.G.; Mohamadi, R.M.; Poudineh, M.; Kermanshah, L.; Ahmed, S.; Safaei, T.S.; Stojcic, J.; Nam, R.K.; Sargent, E.H.; Kelley, S.O. Interrogating Circulating Microsomes and Exosomes Using Metal Nanoparticles. Small 2016, 12, 727–732.

- Reiner, A.T.; Witwer, K.W.; van Balkom, B.W.M.; de Beer, J.; Brodie, C.; Corteling, R.L.; Gabrielsson, S.; Gimona, M.; Ibrahim, A.G.; de Kleijn, D.; et al. Concise Review: Developing Best-Practice Models for the Therapeutic Use of Extracellular Vesicles. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 1730–1739.

- Théry, C.; Clayton, A.; Amigorena, S.; Raposo, G. Isolation and Characterization of Exosomes from Cell Culture Supernatants and Biological Fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2006, 30, 3.22.1–3.22.29.

- Wang, Z.; Wu, H.J.; Fine, D.; Schmulen, J.; Hu, Y.; Godin, B.; Zhang, J.X.J.; Liu, X. Ciliated Micropillars for the Microfluidic-Based Isolation of Nanoscale Lipid Vesicles. Lab. Chip. 2013, 13, 2879–2882.

- Wu, M.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Huang, P.H.; Chen, C.; Li, H.; Li, P.; Quinn, D.; Dao, M.; et al. Isolation of Exosomes from Whole Blood by Integrating Acoustics and Microfluidics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10584–10589.

- Chen, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Du, L. Review on Strategies and Technologies for Exosome Isolation and Purification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 811971.

- Helwa, I.; Cai, J.; Drewry, M.D.; Zimmerman, A.; Dinkins, M.B.; Khaled, M.L.; Seremwe, M.; Dismuke, W.M.; Bieberich, E.; Stamer, W.D.; et al. A Comparative Study of Serum Exosome Isolation Using Differential Ultracentrifugation and Three Commercial Reagents. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 0170628.

- Martins, T.S.; Catita, J.; Rosa, I.M.; da Cruz e Silva, O.A.B.; Henriques, A.G. Exosome Isolation from Distinct Biofluids Using Precipitation and Column-Based Approaches. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 198820.

- Zhang, M.; Jin, K.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, L. Methods and Technologies for Exosome Isolation and Characterization. Small Methods 2018, 2, 21.

- van der Pol, E.; Hoekstra, A.G.; Sturk, A.; Otto, C.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Nieuwland, R. Optical and Non-Optical Methods for Detection and Characterization of Microparticles and Exosomes. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 2596–2607.

- Pisitkun, T.; Shen, R.-F.; Knepper, M.A. Identification and Proteomic Profiling of Exosomes in Human Urine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 13368–13373.

- Wu, Y.; Deng, W.; Klinke, D.J. Exosomes: Improved Methods to Characterize Their Morphology, RNA Content, and Surface Protein Biomarkers. Analyst 2015, 140, 6631–6642.

- György, B.; Szabó, T.G.; Pásztói, M.; Pál, Z.; Misják, P.; Aradi, B.; László, V.; Pállinger, É.; Pap, E.; Kittel, Á.; et al. Membrane Vesicles, Current State-of-the-Art: Emerging Role of Extracellular Vesicles. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 2667–2688.

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular Vesicles: Exosomes, Microvesicles, and Friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383.

- Maas, S.L.N.; de Vrij, J.; van der Vlist, E.J.; Geragousian, B.; van Bloois, L.; Mastrobattista, E.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Wauben, M.H.M.; Broekman, M.L.D.; Nolte-’T Hoen, E.N.M. Possibilities and Limitations of Current Technologies for Quantification of Biological Extracellular Vesicles and Synthetic Mimics. J. Control. Release 2015, 200, 87–96.

- Maas, S.L.N.; de Vrij, J.; Broekman, M.L.D. Quantification and Size-Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles Using Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing. J. Vis. Exp 2014, 92, 51623.

- Shao, H.; Im, H.; Castro, C.M.; Breakefield, X.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, H. New Technologies for Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1917–1950.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, W.H. Exosomes: Biogenesis, Biologic Function and Clinical Potential. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 19.

- Jeyaram, A.; Jay, S.M. Preservation and Storage Stability of Extracellular Vesicles for Therapeutic Applications. AAPS J. 2018, 20, 1.

- Maroto, R.; Zhao, Y.; Jamaluddin, M.; Popov, V.L.; Wang, H.; Kalubowilage, M.; Zhang, Y.; Luisi, J.; Sun, H.; Culbertson, C.T.; et al. Effects of Storage Temperature on Airway Exosome Integrity for Diagnostic and Functional Analyses. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1359478.

- Madison, M.N.; Jones, P.H.; Okeoma, C.M. Exosomes in Human Semen Restrict HIV-1 Transmission by Vaginal Cells and Block Intravaginal Replication of LP-BM5 Murine AIDS Virus Complex. Virology 2015, 482, 189–201.

- Welch, J.L.; Madison, M.N.; Margolick, J.B.; Galvin, S.; Gupta, P.; Martínez-Maza, O.; Dash, C.; Okeoma, C.M. Effect of Prolonged Freezing of Semen on Exosome Recovery and Biologic Activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45034.

- Yuana, Y.; Böing, A.N.; Grootemaat, A.E.; van der Pol, E.; Hau, C.M.; Cizmar, P.; Buhr, E.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Handling and Storage of Human Body Fluids for Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 29260.

- Oosthuyzen, W.; Sime, N.E.L.; Ivy, J.R.; Turtle, E.J.; Street, J.M.; Pound, J.; Bath, L.E.; Webb, D.J.; Gregory, C.D.; Bailey, M.A.; et al. Quantification of Human Urinary Exosomes by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 5833–5842.

- Sivanantham, A.; Jin, Y. Impact of Storage Conditions on EV Integrity/Surface Markers and Cargos. Life 2022, 12, 697.

- Bahr, M.M.; Amer, M.S.; Abo-El-Sooud, K.; Abdallah, A.N.; El-Tookhy, O.S. Preservation Techniques of Stem Cells Extracellular Vesicles: A Gate for Manufacturing of Clinical Grade Therapeutic Extracellular Vesicles and Long-Term Clinical Trials. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2020, 8, 1704992.

- Kusuma, G.D.; Barabadi, M.; Tan, J.L.; Morton, D.A.V.; Frith, J.E.; Lim, R. To Protect and to Preserve: Novel Preservation Strategies for Extracellular Vesicles. Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 1199.

- Budgude, P.; Kale, V.; Vaidya, A. Cryopreservation of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Using Trehalose Maintains Their Ability to Expand Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Vitro. Cryobiology 2021, 98, 152–163.

- Gelibter, S.; Marostica, G.; Mandelli, A.; Siciliani, S.; Podini, P.; Finardi, A.; Furlan, R. The Impact of Storage on Extracellular Vesicles: A Systematic Study. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, 12162.

- Bosch, S.; de Beaurepaire, L.; Allard, M.; Mosser, M.; Heichette, C.; Chrétien, D.; Jegou, D.; Bach, J.M. Trehalose Prevents Aggregation of Exosomes and Cryodamage. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36162.

- Kreke, M.; Smith, R.; Hanscome, P.; Peck, K.; Ibrahim, A. Processes for Producing Stable Exosome Formulations. US Patent US20160158291A, 3 December 2015.

- Charoenviriyakul, C.; Takahashi, Y.; Nishikawa, M.; Takakura, Y. Preservation of Exosomes at Room Temperature Using Lyophilization. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 553, 32.

- Richter, M.; Fuhrmann, K.; Fuhrmann, G. Evaluation of the Storage Stability of Extracellular Vesicles. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 2019, 1–9.

- el Baradie, K.B.Y.; Nouh, M.; O’Brien, F.; Liu, Y.; Fulzele, S.; Eroglu, A.; Hamrick, M.W. Freeze-Dried Extracellular Vesicles From Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Prevent Hypoxia-Induced Muscle Cell Injury. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 181.

- Raimondo, S.; Naselli, F.; Fontana, S.; Monteleone, F.; lo Dico, A.; Saieva, L.; Zito, G.; Flugy, A.; Manno, M.; di Bella, M.A.; et al. Citrus Limon-Derived Nanovesicles Inhibit Cancer Cell Proliferation and Suppress CML Xenograft Growth by Inducing TRAIL-Mediated Cell Death. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 19514–19527.

- Rezaie, J.; Feghhi, M.; Etemadi, T. A Review on Exosomes Application in Clinical Trials: Perspective, Questions, and Challenges. Cell Commun. Signal 2022, 20, 145.

- Chen, Y.S.; Lin, E.Y.; Chiou, T.W.; Harn, H.J. Exosomes in Clinical Trial and Their Production in Compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice. Tzu. Chi. Med. J. 2020, 32, 113–120.

- Teng, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Mu, J.; Sayed, M.; Hu, X.; Lei, C.; Sriwastva, M.; Kumar, A.; Sundaram, K.; et al. Plant-Derived Exosomal MicroRNAs Inhibit Lung Inflammation Induced by Exosomes SARS-CoV-2 Nsp12. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2424–2440.

More