Endometriosis is a chronic disease, defined by abnormal presence of non-neoplastic endometrial glands and endometrial stroma outside the uterine mucosa. MosIt frequently it affects pelvic organs, followed by abdominal locations: ovaries, fallopian tubes, urinary bladder, intestines or peritoneum [1,2]. Occasionally, endometriotic foci are localized in distant organs far outside the pelvis: diaphragm, pleura or lungs, abdominal wall, central or peripheral nervous system [2]. According to the World Health Organization data, approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women (190 million) are diagnosed with this condition worldwide [1]. Endometriosis is mainly found in girls and ladies of reproductive age. The number of diagnosed cases peaks between 25 and 45 years of age [3], but it may take up to 8–10 years to reach the definitive diagnosis, as the clinical manifestations are diverse, non-specific and not always recognized as a pathology even by the patient herself. Endometriosis has a considerable impact on worldwideis notable both for its undesirable clinical and economics as well – it costs the world over 80 billion USD per year [5].

Endometriosial cons has a wide range of manifestations – from accidentally found asymptomatic lesions to a severe condition [3]. The main symptoms caused by endometriosis are chronic pelvic pain, severely painful menstrual periods, dyspareunia, dysuria and/or painful defecation, abdominal bloating and constipation. Infertility represents another endometriosis-related major problem: 40–50% of infertile women are diagnosed with endometriosis [2,5]. There are different mechanisms how endometriosis can decrease fertility: distorted anatomy of the pelvic cavity, development of the adhesions, fibrosis of the fallopian tubes, local inflammation of the pelvic organs and tissues, systemic and local (i.e., endometrial) immune dysregulation, changes in hormonal environment inside the uterus and/or impaired implantation of the embryo [3]. In addition, the disease has a significant negative impact on the quality of life and social well-being of patients – due to pain and other symptoms, equences.g., fatigue, severe bleeding or mood swings, women have to skip their studies or work and might tend to avoid sex. Endometriosis may increase the risk of secondary mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression.

Three subtypes of endometriosis are recognised: superficial peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriotic cysts and deep infiltrating endometriosis. Superficial peritoneal endometriosis is found on the surface of pelvic organs and the peritoneum. Ovarian endometriotic cysts are fluid-filled cavities, known also as endometriomas or “chocolate cysts”. Deep infiltrating endometriosis can invade pelvic or extrapelvic viscera to the depth of 5 mm or more, distorting the local anatomy [6].

Since the disease was descriince endometriosis was described, several pathogenetic pathways have been cproponsidersed, including retrograde menstruation, so-called benign metastasis, immune dysregulation, coelomic metaplasia, hormonal disbalance, involvement of stem cells and alterations in epigenetic regulation. These theories are highlighted in the given entry.

- endometriosis

- pathogenesis

- immune regulation

- oestrogen

- progesterone

- stem cells

- metaplasia

- epigenetics

- carcinogenesis

- retrograde menstruation

1. Endometriosis: The Definition and Essential Features

As was noted, endometriosis is a chronic disease, defined by abnormal presence of non-neoplastic endometrial glands and endometrial stroma outside the uterine mucosa. Most frequently it affects pelvic organs, followed by abdominal locations: ovaries, fallopian tubes, urinary bladder, intestines or peritoneum [1,2]. Occasionally, endometriotic foci are localized in distant organs far outside the pelvis: diaphragm, pleura or lungs, abdominal wall, central or peripheral nervous system [2]. According to the World Health Organization data, approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women (190 million) are diagnosed with this condition worldwide [1]. Endometriosis is mainly found in girls and ladies of reproductive age. The number of diagnosed cases peaks between 25 and 45 years of age [3], but it may take up to 8–10 years to reach the definitive diagnosis, as the clinical manifestations are diverse, non-specific and not always recognized as a pathology even by the patient herself. Endometriosis has a considerable impact on worldwide economics as well – it costs the world over 80 billion USD per year [5].

Endometriosis has a wide range of manifestations – from accidentally found asymptomatic lesions to a severe condition [3]. The main symptoms caused by endometriosis are chronic pelvic pain, severely painful menstrual periods, dyspareunia, dysuria and/or painful defecation, abdominal bloating and constipation. Infertility represents another endometriosis-related major problem: 40–50% of infertile women are diagnosed with endometriosis [2,5]. There are different mechanisms how endometriosis can decrease fertility: distorted anatomy of the pelvic cavity, development of the adhesions, fibrosis of the fallopian tubes, local inflammation of the pelvic organs and tissues, systemic and local (i.e., endometrial) immune dysregulation, changes in hormonal environment inside the uterus and/or impaired implantation of the embryo [3]. In addition, the disease has a significant negative impact on the quality of life and social well-being of patients – due to pain and other symptoms, e.g., fatigue, severe bleeding or mood swings, women have to skip their studies or work and might tend to avoid sex. Endometriosis may increase the risk of secondary mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression.

Three subtypes of endometriosis are recognised: superficial peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriotic cysts and deep infiltrating endometriosis. Superficial peritoneal endometriosis is found on the surface of pelvic organs and the peritoneum. Ovarian endometriotic cysts are fluid-filled cavities, known also as endometriomas or “chocolate cysts”. Deep infiltrating endometriosis can invade pelvic or extrapelvic viscera to the depth of 5 mm or more, distorting the local anatomy [6]. As highlighted further, these types can develop via different pathogenetic pathways.

Since the disease was described, several pathogenetic pathways have been considered, including retrograde menstruation, so-called benign metastasis, immune dysregulation, coelomic metaplasia, hormonal disbalance, involvement of stem cells and alterations in epigenetic regulation. These theories are discussed below.

2. Retrograde Menstruation

23. Benign Metastasis

34. Immune Dysregulation

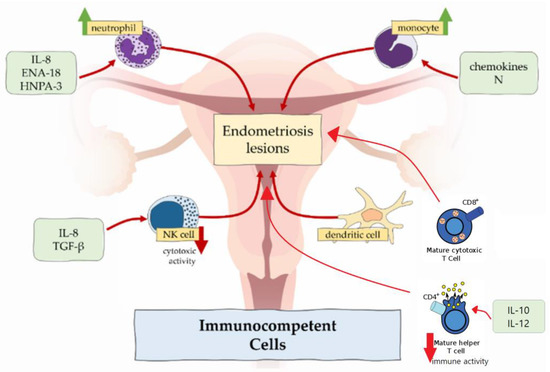

In endometriosis, number of macrophages is increased in eutopic endometrium [21,22] and peritoneal fluid [10] across all phases of menstrual cycle, but the cyclic changes are absent [23]. In contrast to higher density of macrophages, the phagocytic function is decreased because of the reduced expression of CD3, CD36 and annexin A2 [10,21,24]. It results in incomplete endometrial shedding, presence and survival of desquamated tissue in the peritoneal cavity [21]. Peritoneal macrophages release proinflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, which recruit neutrophils, provoke inflammation and support the development of endometrial lesions [3,10]. Macrophages also produce VEGF, which promotes angiogenesis in endometriosis [10].

Some authors noted predominance of M2 macrophage subtype in endometriotic lesions and peritoneal cavity [10,25]. This subtype classically promotes development of the tumours, e.g., colorectal cancer and osteosarcoma. M2 enhances nerve fibre growth, so excess of M2 macrophages could be related to severe pain, experienced in women with endometriosis [21,22].

In healthy endometrium, neutrophils are involved in endometrial repair and regulation of cyclic vascular proliferation. In endometriosis, neutrophil counts in peritoneal fluid are elevated. This could be attributable to the locally increased concentration of chemoattractants secreted by epithelial cells such as IL-8, epithelial neutrophil-activating peptide 8 (ENA-78) and human neutrophil peptides 1-3 (HNP1-3), which attract neutrophils to the peritoneal cavity [10,21].

According to the results in the mouse model, depleting of neutrophils with anti-Gr-1 antibody in the early stage of endometriosis significantly decreased the number of endometrial lesions [26]. In contrast, this antibody had no effect in advanced disease, which suggested that neutrophils did not take part in endometriosis progression, but only in induction [10]. However, neutrophils express cytokines, e.g., VEGF, IL-8 and C-X-C chemokine motif ligand 10 (CXCL10), which cause progression of the disease [10].

NK cells normally produce cytokines, which control tumour immunity and microbial infections. Regarding endometriosis, their cytotoxic function is suppressed by the IL-6, IL-15 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) [10,27]. Therefore, endometrial cells, which enter the peritoneal cavity, tend to stay there. However, the amount of the NK cells shows no differences in women with and without endometriosis.

Dendritic cells are responsible for antigen presentation to T cells and, therefore, are involved in immune responses in mucosal surfaces [22]. There are two types of dendritic cells—plasmocytoid dendritic cells and myeloid dendritic cells. Plasmocytoid dendritic cells function in recognition of viruses and produce interferons, while myeloid dendritic cells participate in T cell activation and are relevant to endometriosis. In healthy individuals, the amount of the dendritic cells increases to clear endometrial debris during menstruation. In ladies affected by endometriosis, the density of myeloid dendritic cells in endometrium is significantly reduced [28]. In the peritoneal cavity, numbers of dendritic cells are increased and may promote neuroangiogenesis, causing and enhancing pain sensation [22].

One of the important factors, which maintains the development of endometriosis, is imbalance between type 1 T lymphocytes (Th1) and type 2 T lymphocytes (Th2). These two types have different immune functions: Th1 lymphocytes produce cytokines and promote cellular responses, but Th2 lymphocytes influence differentiation of B lymphocytes and suppress cellular and humoral responses [3]. In endometriosis, Th2 lymphocytes represent the main population of T cells, allowing potentially harmful cells to escape from immune surveillance. On the other hand, the immune response of CD4+ Th1 lymphocytes in peritoneal fluid is suppressed due to an increased expression of IL-10 and IL-12 [29].

Moreover, the peripheral concentration of cytotoxic (CD8+) T cells and activated (HLA-DR) T cells in healthy women increases in luteal phase compared with the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, but there are no such fluctuations of cytotoxic and activated T cells in patients with endometriosis [30].

Recently, the association between regulatory T cells (Tregs) and endometriosis was reported. The main function of regulatory T cells is the modulation of the immune system, maintaining tolerance to self-antigens and preventing autoimmune diseases [29]. In endometriosis patients, there is an increased amount of Tregs in the peritoneal fluid and decreased – in the peripheral blood. These changes can suppress local cellular immune response and facilitate autoimmune reactions [29].

45. Coelomic Metaplasia

56. Embryonic Rest Theory

67. Endometrial Stem Cell Theory

78. Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cell Recruitment Theory

89. Hormonal Imbalance

The main functions of oestrogen in healthy endometrium include stimulation of epithelial proliferation and induction of leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF), an IL-6 family cytokine, which is important for successful embryo implantation and decidualization of the endometrium [38].

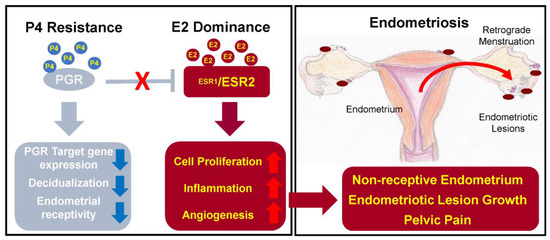

In endometriosis, studies report on higher levels of oestradiol – oestrogen steroid hormone – in menstrual blood and abnormal expression of enzymes involved in oestrogen metabolism, which can lead to increased oestrogen concentration and suppressed inactivation of oestrogen synthesis [40].

There are two oestrogen receptors – ERα and ERβ, which are coded by different genes: ESR1 and ESR2, respectively [38,39]. In endometriosis patients, expression of the receptors is changed – the ERα:ERβ ratio is significantly reduced due to high ERβ levels [41]. The main problem caused by abnormal expression of ERα is increased synthesis of inflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, angiogenic and growth factors [20,29]. On the other hand, ERβ overexpression leads to inhibition of TNFα-induced apoptosis and also promotes the inflammation [27,41]. As a result, synthesized prostaglandins induce inflammation and prevent cell apoptosis; growth factors and angiogenic agents support the progression of the endometrial lesions, and inhibition of apoptosis promotes cell proliferation and lesion growth [20,27]. In addition, oestrogen is able to stimulate growth of peripheral nerve fibres by upregulating nerve growth factors (NGF) causing nociceptive pain [27].

The expression of the progesterone receptor (PGR) is induced by oestrogen action through its receptor ERα. PGR has two isoforms: PR-A and PR-B, expression of which increase during the proliferative phase and decrease after the ovulation [41]. Expressed PGR inhibits ERα expression, establishing a feedback system.

In endometriosis, as a result of low ERα:ERβ ratio and high oestrogen levels, progesterone resistance develops: PR-B is undetectable and PR-A levels are significantly lower than in the endometrium of healthy individuals [41]. Progesterone resistance manifests as a decreased responsiveness to progesterone of endometrial stromal cells [2].

Moreover, mutation of PGR gene causes sterility in mice due to reduced or absent ovulation, uterine hyperplasia, lack of decidualization of the endometrium and limited mammary gland development [38].

Due to the significant impact of oestrogen and progesterone on pathogenesis of endometriosis, several treatment approaches target the balance of these hormones. Current therapy options include combined oral contraceptives, progestins, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, danazol and aromatase inhibitors. Other therapeutic pathways are under development, e.g., gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists, selective oestrogen receptor modulators and selective progesterone receptor modulators [3,38]. However, hormonal therapy is associated with adverse systemic effects including weight gain, fluid retention, acne, hot flashes, decreased libido, insomnia and vaginal dryness [3], which might decrease the compliance to long-term hormonal treatment.

910. Alterations in Epigenetic Regulation

DNA methylation depends on DNA methyltransferases. Normally, the expression of these enzymes in endometrium is regulated by oestrogen and progesterone and varies depending on the cycle phase [42]. In endometriosis, hypermethylation of DNA of the local cells occurs due to increased expression of DNA methyltransferases DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B [39,43].

Human Homeobox A10 (HOXA10) genes are important for the endometrial changes throughout the normal menstrual cycle – they regulate endometrial growth, differentiation, and embryo implantation [39,44]. HOXA10 expression is regulated by oestrogen and progesterone [39]. In endometriosis, the expression of HOXA10 is decreased during the secretory phase, and, as the result, uterine receptivity is decreased and endometriosis-related infertility occurs [39,43]. Probably, HOXA10 gene expression is reduced due to hypermethylation of the HOXA10 gene promoter in the endometrial tissue [39,43].

Histone deacetylases are responsible for histone modulation and acetylation. In endometriosis, activity of histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 is increased. It leads to the hypoacetylation of cyclins, which causes cell cycle induction and propagation [42,43].

110. Micro-RNAs

Micro-RNAs are short non-coding RNA molecules that regulate translation of mRNA post-transcriptionally by repression and mRNA degradation, acting as large-scale molecular switches [45]. According to recent findings, endometriosis is characterised by abnormal spectrum of micro-RNAs, further influencing the expression of the relevant target mRNAs [45]. Wide spectrum of micro-RNAs are involved in different steps of endometriosis. For example, miRNA-135a/b, regulating HOXA10, is upregulated in endometriosis and cause progesterone resistance [42,46]. MiR-199 is downregulated, so COX-2 translation is not suppressed, and it leads to pro-inflammatory milieu, characterised by active prostaglandin synthesis and elevated concentration of IL-8 [42,45]. MiRNA-96b is also downregulated, and it is the cause of increased proliferation in endometrial lesions [42]. MiR-126 increases VEGF and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signalling in endothelial cells, resulting in neoangiogenesis and the subsequent maturation of the new vasculature [45]. MiRNA-223 also shows a significant impact on endometriosis. This micro-RNA is involved in signal transduction, regulation of transcription, cell growth and development, modulation of inflammation and tumorigenesis [47]. In 2022, Xue et al. found that miRNA-223 levels are decreased in eutopic and ectopic endometrial stromal cells in women with endometriosis [47]. They also proved that upregulation of miRNA-223 would lead to suppressed proliferation, invasion and migration of endometrial stromal cells and reversed epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [47]. These findings highlight miRNA-223 as a potential new therapeutic target. The other micro-RNA, which promotes the growth, proliferation and angiogenesis of ectopic stromal cells, is miRNA-21 [46,48]. In the serum of endometriosis patients, expression of miR-26b-5p and miR-215-5p is downregulated, but miR-6795-3p (Table 1) – upregulated [48]. These three micro-RNAs are involved in MAPK and PI3K-Akt molecular pathways. MAPK signalling is important in regulation of inflammation and the following cellular processes: differentiation, proliferation, stress response, metabolism and apoptosis [48]. PI3K-Akt pathway is also involved in the listed cellular reactions as well as in angiogenesis. These two molecular cascades are significant for development and progression of endometriosis, theoretically becoming future therapeutic targets.|

Micro-RNAs |

Changes |

Effect |

|---|---|---|

|

miRNA-135a/b |

Upregulated |

Abnormal regulation of HOXA10 expression, progesterone resistance |

|

miR-199 |

Downregulated |

Synthesis of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins due to lack of COX-2 suppression |

|

miRNA-96b |

Downregulated |

Increased proliferation of the endometrial lesions |

|

miR-126 |

Upregulated |

Neoangiogenesis due to increased levels of VEGF and FGF |

|

miRNA-223 |

Downregulated |

Proliferation, invasion, migration of endometrial stromal cells, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

|

miRNA-21 |

Upregulated |

Growth, proliferation and angiogenesis of ectopic stromal cells |

|

miR-26b-5p |

Downregulated |

Activation of MAPK and PI3K-Akt pathways: inflammation, cell growth, differentiation and proliferation, angiogenesis |

|

miR-215-5p |

Downregulated |

|

|

miR-6795-3p |

Upregulated |

112. Carcinogenetic Pathways in Endometriosis

Although endometriosis is a benign disease, it still has a potential to transform into malignancy. This event is rather rare, affecting 1% of all endometriosis patients [39,45]. Endometriosis-related malignant change most frequently takes place in ovaries, and the predominant endometriosis-related ovarian tumours are ovarian endometrioid carcinoma and ovarian clear cell carcinoma, which are found in 76% of the relevant cases [39,49]. Recently, several carcinogenetic pathways have been reported for endometriosis-related malignant transformation. Uncontrolled cell division, infiltration of surrounding tissues, neoangiogenesis and escape of apoptosis can be caused by the demethylation of oncogenes and the hypermethylation of tumour suppressor genes [39]. This has been demonstrated in endometriosis. For example, the following events are involved in malignant change of the endometriosis: the hypermethylation of the human mutL homolog 1 (hMLH1) gene promoter which causes a decrease in DNA mismatch repair gene expression, the hypomethylation of long interspersed element-1 (LINE-1), inactivation of the tumour suppressor genes runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3) gene and Ras-association domain family member 2 (RASSF2) gene by their promoter hypermethylation [39]. Also, in case of endometrioid cancer, activation of the KRAS oncogene and inactivation of the PTEN tumour suppressor gene occurs [44,49]. Loss of PTEN activity is supposed to be an early event in malignant transformation of endometriosis, and is related to the mutation of PTEN gene itself [45]. In addition, Anglesio et al. found that in deep infiltrating endometriosis there are somatic mutations in cancer driver genes ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, and PPP2R1A [50].123. External Environmental Factors

Environmental factors are suspected to have an impact on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. The main potentially harmful lifestyle factors include lack of physical activity, smoking, caffeine and alcohol intake, as well as diet. It is supposed that physical activity helps to reduce the risk of endometriosis, because it decreases menstrual flow and normalizes oestrogen balance [46]. Tobacco smoking increases the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, disrupts synthesis of prostaglandin E2 and natural steroids [46]. Disrupted steroidogenesis leads to increased oestrogen and decreased progesterone synthesis [51]. Caffeine reduces production of sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG) [46]. It is suggested that caffeine might have a protective potential, but the published data are conflicting. Kechagias et al. found a correlation between endometriosis and intense caffeine intake (>300 mg/day), admitting that it could be the risk factor for the disease [52]. Alcohol has the opposite effect on synthesis of hormones compared to caffeine. It has an impact on pituitary luteinizing hormone and activates the enzyme aromatase, resulting in increased oestrogen production and increased testosterone conversion to oestrogen [46,51]. Increased consumption of red meat is considered to have a negative effect on endometriosis development, probably because of high content of saturated fat [51,53].Dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are organic pollutants produced by industrial processes. The most toxic environmental pollutant is called 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) [53]. PCB and TCDD may disrupt endocrine processes. In context of endometriosis, it was found that increased amount of PCB and TCDD have been accumulated in adipose tissue of patient with deep infiltrating endometriosis [51,54], but the mechanism of these changes remained uncertain.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the pathogenesis of endometriosis is complex. Retrograde menstruation, so-called benign metastasis, immune dysregulation, coelomic metaplasia, embryonic rest theory, recruitment of endometrial and/or bone marrow-derived stem cells, hormonal imbalance, alterations in epigenetic regulation and micro-RNA spectrum as well as influence of external environmental factors are among the proposed theories and research directions in endometriosis. There is no single theory which could explain all aspects of endometriosis. The future concept of endometriosis is likely to incorporate elements from all the listed pathogenetic theories.