Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Peter Tang and Version 1 by João L. Viana.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is a global health burden with high mortality and health costs. CKD patients exhibit lower cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, strongly associated with morbidity/mortality, which is exacerbated when they reach the need for renal replacement therapies (RRT). Muscle wasting in CKD has been associated with an inflammatory/oxidative status affecting the resident cells’ microenvironment, decreasing repair capacity and leading to atrophy.

- chronic kidney disease

- skeletal muscle wasting

- reactive oxygen species (ROS)

1. Introduction

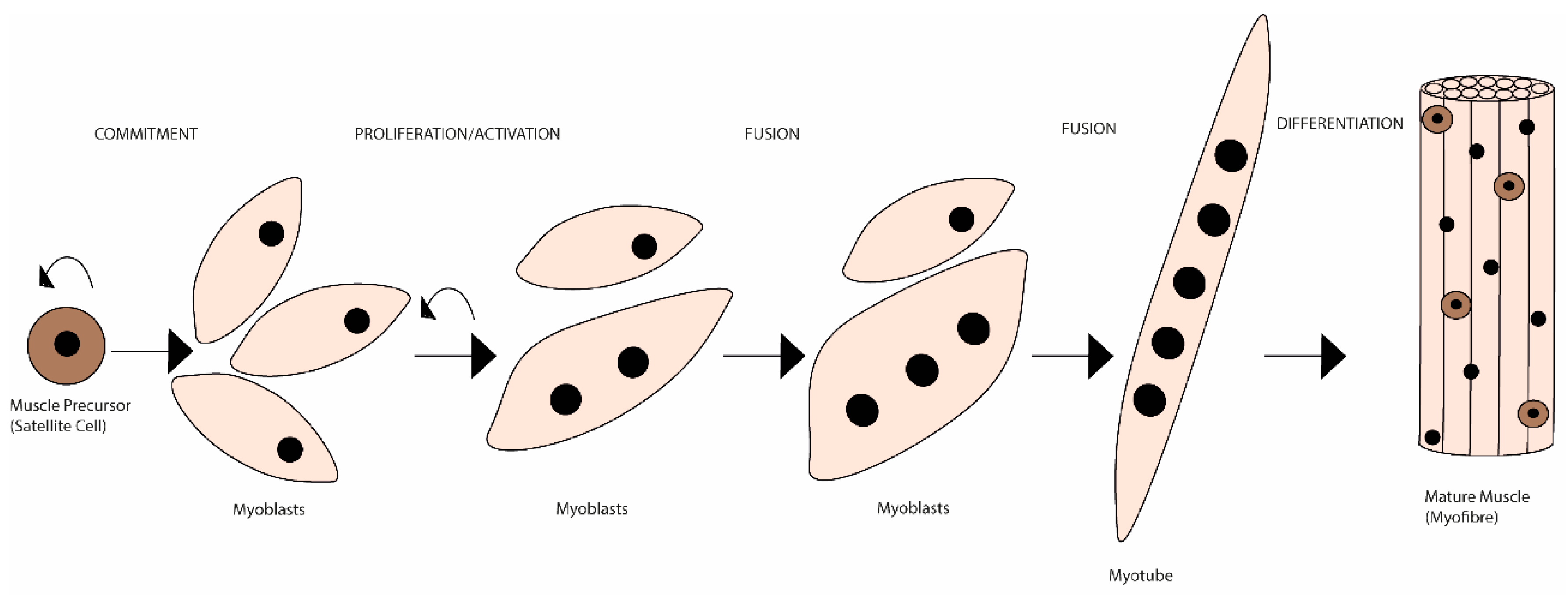

Unlike de novo embryonic muscle formation, adult myogenesis or muscle regeneration in higher vertebrates depends on the extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold remaining (after tissue damage), serving as a template for the muscle fibres [1]. The mechanisms of embryonic myogenesis are to some extent recapitulated during muscle regeneration (see [2,3][2][3] for a more detailed description). In brief, it is during embryonic myogenesis that the first muscle fibres are generated [4]. These are derived from mesoderm structures and are the template fibres for the following wave of additionally generated ones [5,6][5][6]. Initially, an exponential proliferation occurs up to a degree where the number of fabricated myonuclei starts decreasing, up until a steady state of synthesis rate is reached [7,8][7][8]. This leads to the establishment of a matured muscle, followed by quiescence of the progenitor cells and its occupation within the muscle fibres as satellite cells [9,10][9][10]. The myogenic rely on the satellite cells’ capacity to become activated, and to proliferate and differentiate (including self-renewal), ensuring an efficient muscle repair [11]. Satellite cells exist in a dormant state (i.e., quiescence or reversible G0 state), retaining the ability to reverse to a proliferative state in response to injury, which is essential for satellite cell pool long-term preservation [12,13,14][12][13][14]. Both timing and extension of satellite cells’ activation and subsequent myoblasts’ migration, in response to myotraumas to the injury sites, are partly regulated by a plethora of autocrine and paracrine factors [15,16][15][16]. These factors are released either from damaged myofibres, by the ECM or secreted by supporting inflammatory (e.g., neutrophils, macrophages) and interstitial cells, present in the niche or that migrate to the site following injury [17]. Moreover, cell-to-cell interactions are fundamental both during developmental (i.e., embryogenesis) and regenerative myogenesis [i.e., in response to physical activity (PA), trauma or disease]. These interactions allow myoblasts to adhere and fuse with myotubes during myogenesis (initial stage) [18] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the mammalian skeletal myogenesis process. Upon muscle injury, a resident population of quiescent skeletal muscle satellite cells can become activated, start to proliferate and differentiate into myoblasts. Over the course of several days, these myoblasts fuse together to form multinucleated myotubes. Further, myoblasts can also fuse to the already existing myotubes to create even larger myotubes, which will eventually align to form muscle fibres. This whole process is regulated by many internal and external cues.

Satellite cells sit closely opposed to the myofibres or near capillaries, facilitating their nutrition, sitting within the ECM, which functions as a scaffold to facilitate their purpose [19,20][19][20]. Additionally, activated satellite cells undergo symmetric—give rise to two identical daughter-cells that will self-renew satellite stem cell pools—and asymmetric division—generate one stem cell and one daughter-cell committed to progress through the myogenic lineage and eventually will join the myofibre, ensuring repetitive rounds of regeneration [21,22][21][22]. These myofibres are formed by myoblast fusion, producing multinucleated myotubes, further maturing into myofibres (see [23,24][23][24] for details). Each myofibre is surrounded by a specialised basal lamina (BL)—endomysium—that harbours a specialised plasma membrane—sarcolemma—allowing neuronal signal transduction and structural stability [25,26][25][26]. The sarcolemma is anchor to the BL through transmembrane proteins—dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex (DGC)—which allow the connection of cytoskeleton to ECM [27].

Muscle fibres are the base of skeletal muscle, being their basic contractile units [28]. These fibres are surrounded by a layer of connective tissue and are grouped in bundles [25,26][25][26]. Each myofibre is connected to a single motor neuron and expresses characteristics (e.g., molecules and metabolic enzymes) for contractile function, specifying the myofibre contractile properties, ranging from slow-contracting, fatigue-resistant/oxidative (type I) to fast-contracting, non-fatigue-resistant/glycolytic (type II) fibres. Moreover, the proportion of each fibre type determines overall contractile property within the muscle [29]. The connective tissue that surrounds the skeletal muscle functions as a framework, combining myofibres with myotendinous junctions (i.e., the place where myofibres attach to the skeleton), transforming myofibre contraction into movement [30]. Hence, the skeletal muscle functional properties are dependent on myofibres, motor neurons, blood vessels and ECM.

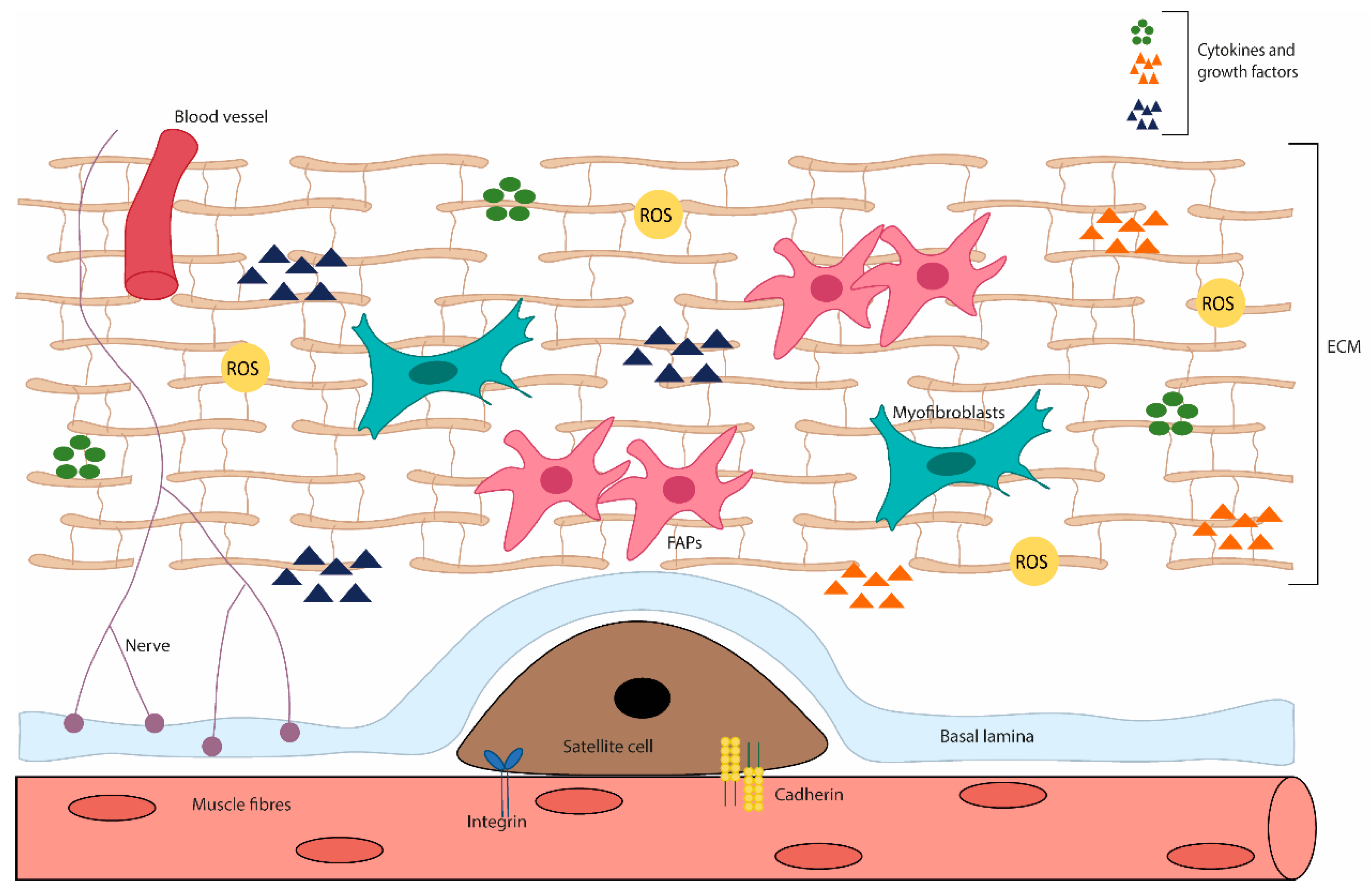

2. REDOX Imbalance as a Mechanism of Muscle Wasting

Skeletal muscle atrophy is a process that occurs as a result of conditions such as disuse, malnutrition, aging and in certain states of disease. Nonetheless, it is characterized firstly by a decrease in muscle mass (and volume), force production and, on a more detailed perspective, by a diminishment of protein content and fibre diameter [35][31]. Moreover, the primary loss in muscle strength that occurs with atrophy results from the rapid destruction of myofibrils, the contractile machinery of the muscle, constituting around >70% of the muscle protein [36][32]. Among all the potential aetiological foundations of muscle wasting, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, including the oxidative damage and/or the defective redox signalling, has stood out as the possible main explanation [37,38,39][33][34][35]. ROS are reactive molecules that contain oxygen, and this family is comprised of free radicals (i.e., species with at least one unpaired electron) and nonradical oxidants (i.e., species with their electronic ground state complete). The chemical reactivity of the various ROS molecules is vastly different; for instance, hydroxyl (●OH), the most unstable, reacts immediately upon formation with biomolecules in its vicinities, whereas hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is capable of crossing cell membranes to exert its effects beyond its original compartment [40,41,42][36][37][38]. ROS are generated by various sources, mainly endogenous sources, including mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) activity, microsomal cytochrome P450 and xanthine oxidase; and exogenous sources such as ultraviolet radiation, X- and gamma (γ)-rays, ultrasounds, pesticides, herbicides, and xenobiotics [43][39]. Superoxide anion (O2-●) is the most frequently generated radical, under physiological conditions. Its main source is the inner mitochondrial membrane, in the complexes I and III, during respiratory chain, by the inevitable electron leakage to O2 [44,45][40][41]. It can also be generated in the short transport chain of endoplasmic reticulum upon electron leakage and during NOX activity, by transferring one electron from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) to O2 [46][42]. To cope with ROS, the cells have developed control systems to regulate oxidation/reduction balance, since redox balance is critical. A key component is the antioxidant system, which prevents ROS accumulation and deleterious actions. The cells contain both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants that work by mitigating ROS effects and by drastically delaying/preventing oxidation from happening. Key enzymatic antioxidants are superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and thioredoxin (Trx), whereas non-enzymatic are mainly vitamin C (ascorbic acid) and E (tocopherol), zinc and selenium, glutathione, plant polyphenols and carotenoids [47,48][43][44]. These act primarily by using three different strategies: (1) scavenging ROS; (2) converting ROS molecules into less reactive ones, and (3) chelation via metal binding proteins. Throughout the cells, antioxidants are compartmentalized in both organelles and cytoplasm, but also exist in the interstitial fluid and blood [49][45]. ROS are normal products of cell metabolism with significant physiological roles. They regulate signalling pathways (redox signalling) by changing the activity of structural proteins, transcription factors, membrane receptors, ion channels and protein kinases/phosphatases [50,51][46][47]. ROS physiological roles depend partly on antioxidant control, establishing a redox balance. When redox homeostasis is disrupted, due to the rising of ROS levels and the unlikely neutralization by the antioxidant defence, a state referred to as oxidative stress (OS) occurs. This leads to an impairment of redox signalling and induces molecular damage to biomolecules [52,53][48][49]. Moreover, OS has a graded response, with minor or moderated changes provoking an adaptive response and homeostasis restoration, whereas violent perturbations lead to pathological insults, damage beyond repair and may even lead to cell death [53][49]. Interestingly, something that is not appreciated often is that our understanding of “low” or “high” response regarding ROS levels is somewhat imprecise, redox time-courses in vivo are scarce and our knowledge is based of immunohistochemical analysis or measuring more stable elements of the family [54,55][50][51]. As in other tissues, redox signalling in skeletal muscle has important roles, being the base of skeletal muscle function to elicit exercise adaptation. It supports the neuromuscular development and the long-term remodelling/adaptation of contractile activity [56,57][52][53]. Moreover, regulated ROS levels are also involved in skeletal muscle regeneration, regulating the activity of skeletal muscle stem cells, through redox-sensitive signalling pathways [58][54] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Diagram of the skeletal muscle microenvironment. This niche is composed of various cell types and ECM proteins. In adult skeletal muscle, the quiescent satellite cells stand on the myofiber, under the basal lamina, being surrounded by the ECM, containing blood vessels, nerves, immune cells, fibro-adipogenic progenitors (FAPs), adipocytes and myofibroblast. The satellite cell states are regulated by their interactions with the surrounding microenvironment, direct interaction (e.g., M-cadherin) between muscle fibres and satellite cells; or interact with a variety of components of the ECM and cytokines and growth factors. In addition, stromal cells present can physically interact with satellite cells and release cytokines, growth factors and ECM components, which influence the behaviour of satellite cells, contributing to muscle growth, homeostasis and regeneration.

3. REDOX Imbalance in CKD

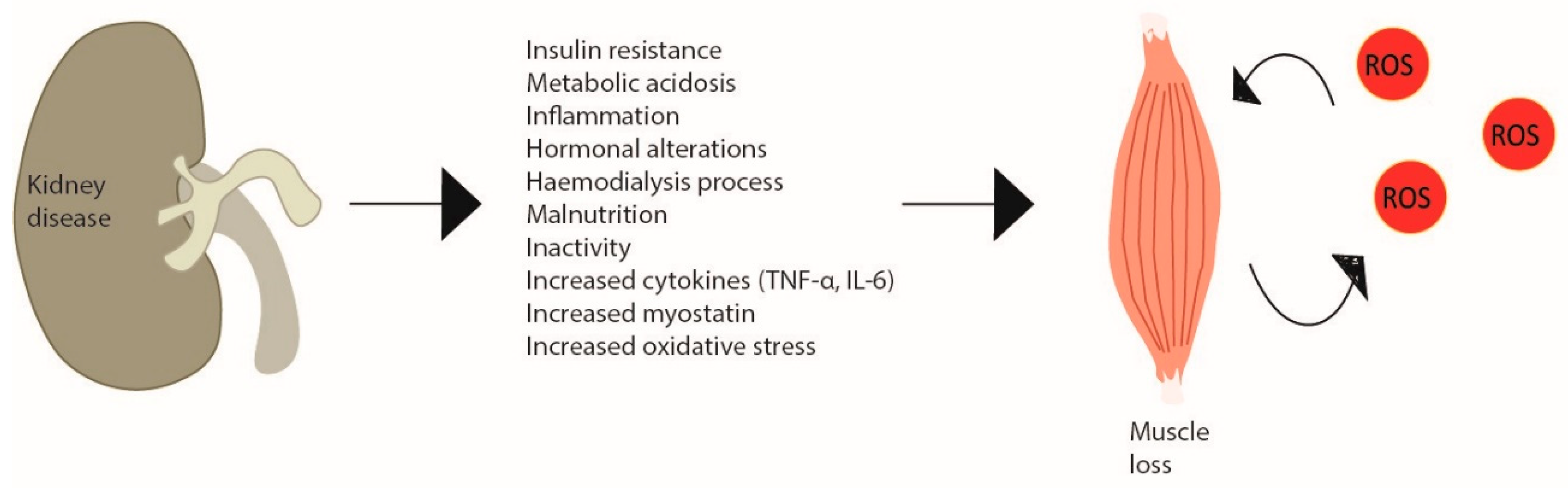

CKD consists of a progressive and irreversible loss of kidney function in that, in the more advanced stages of the disease, patients require renal replacement therapy or renal transplantation [75][71]. The aetiologic factors of the myopathy observed in CKD patients are diverse, from the kidney disease itself, regardless of the need for renal replacement therapy, to the actual dialysis treatment and the typical chronic low-grade inflammation [76,77][72][73]. The skeletal muscle fibres of CKD patients present several abnormalities, such as changes in the capillarity, contractile proteins and enzymes [78][74]. In dialytic patients, this occurs to a greater extent to those who do not undergo dialysis, where atrophy is normally particularly observed in type II fibres [78][74]. This can be partially explained by the substantial amino acid loss during dialysis, a reduced energy and protein intake and low PA levels, which are recognised to be even lower on dialysis days [79,80,81][75][76][77]. In fact, these patients present a catabolic environment due to a dysregulated state of energy and protein balance, which includes altered muscle protein metabolism—increased protein degradation (e.g., activation of ubiquitin–proteasome system) (more noticeable) and decreased protein synthesis (e.g., suppressed IGF-1 signalling) (less observed)—and impaired muscle regeneration—satellite cell dysfunction [82][78]. Furthermore, the haemodialysis procedure itself can stimulate protein degradation and reduce protein synthesis, persisting for 2 h after dialysis [83][79]. Moreover, even though increasing protein intake (and calories) could enhance protein turnover, the haemodialysis responses were not fully corrected [84,85,86][80][81][82]. CKD has been previously described as a model of ‘premature’ or ‘accelerated’ ageing, associated with a redox imbalance. However, since the mechanisms of age-related muscle loss are similar, but not the same as the CKD-induced, it may be proposed that the two-simile combined amplifies the dysregulated mechanisms [87,88][83][84] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Skeletal muscle wasting induced by chronic kidney disease. Chronic kidney disease creates metabolic changes due to inflammation, haemodialysis increased cytokine production and myostatin and especially oxidative stress, which leads to skeletal muscle atrophy inducing a catabolic program and a vicious cycle of ROS production in site. In CKD patients, this is observed by decreased muscle strength and increased weakness.

References

- Ciciliot, S.; Schiaffino, S. Regeneration of mammalian skeletal muscle. Basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 906–914.

- Bentzinger, C.F.; Wang, Y.X.; Rudnicki, M.A. Building muscle: Molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a008342.

- Schiaffino, S.; Mammucari, C. Regulation of skeletal muscle growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB pathway: Insights from genetic models. Skelet. Muscle 2011, 1, 4.

- Tajbakhsh, S. Skeletal muscle stem cells in developmental versus regenerative myogenesis. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 266, 372–389.

- Sambasivan, R.; Tajbakhsh, S. Skeletal muscle stem cell birth and properties. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 18, 870–882.

- Parker, M.H.; Seale, P.; Rudnicki, M.A. Looking back to the embryo: Defining transcriptional networks in adult myogenesis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 497–507.

- Schultz, E. Satellite cell proliferative compartments in growing skeletal muscles. Dev. Biol. 1996, 175, 84–94.

- Davis, T.A.; Fiorotto, M.L. Regulation of muscle growth in neonates. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2009, 12, 78–85.

- Schmalbruch, H.; Lewis, D.M. Dynamics of nuclei of muscle fibers and connective tissue cells in normal and denervated rat muscles. Muscle Nerve 2000, 23, 617–626.

- Pellettieri, J.; Alvarado, A.S. Cell turnover and adult tissue homeostasis: From humans to planarians. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007, 41, 83–105.

- Zhao, P.; Hoffman, E.P. Embryonic myogenesis pathways in muscle regeneration. Dev. Dyn. 2004, 229, 380–392.

- Bjornson, C.R.R.; Cheung, T.H.; Liu, L.; Tripathi, P.V.; Steeper, K.M.; Rando, T.A. Notch signalling is necessary to maintain quiescence in adult muscle stem cells. STEM CELLS 2012, 30, 232–242.

- Mourikis, P.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Sambasivan, R.; Tajbakhsh, S. Cell-autonomous Notch activity maintains the temporal specification potential of skeletal muscle stem cells. Development 2012, 139, 4536–4548.

- Forcina, L.; Miano, C.; Pelosi, L.; Musarò, A. An overview about the biology of skeletal muscle satellite cells. Curr. Genet. 2019, 20, 24–37.

- Griffin, C.A.; Apponi, L.H.; Long, K.K.; Pavlath, G.K. Chemokine expression and control of muscle cell migration during myogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123 Pt 18, 3052–3060.

- Gonzalez, M.L.; Busse, N.I.; Waits, C.M.; Johnson, S.E. Satellite cells and their regulation in livestock. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skaa081.

- Tidball, J.G.; Wehling-Henricks, M. Evolving therapeutic strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Targeting downstream events. Pediatr. Res. 2004, 56, 831–841.

- Pavlath, G.K. Current progress towards understanding mechanisms of myoblast fusion in mammals. In Cell Fusions: Regulation and Control; Larsson, L.-I., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 249–265.

- Christov, C.; Chrétien, F.; Abou-Khalil, R.; Bassez, G.; Vallet, G.; Authier, F.J.; Bassaglia, Y.; Shinin, V.; Tajbakhsh, S.; Chazaud, B.; et al. Muscle satellite cells and endothelial cells: Close neighbors and privileged partners. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 1397–1409.

- Mauro, A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1961, 9, 493–495.

- Kuang, S.; Kuroda, K.; Le Grand, F.; Rudnicki, M.A. Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell 2007, 129, 999–1010.

- Troy, A.; Cadwallader, A.B.; Fedorov, Y.; Tyner, K.; Tanaka, K.K.; Olwin, B.B. Coordination of satellite cell activation and self-renewal by Par-complex-dependent asymmetric activation of p38α/β MAPK. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 541–553.

- Abmayr, S.M.; Pavlath, G.K. Myoblast fusion: Lessons from flies and mice. Development 2012, 139, 641–656.

- Lemke, S.B.; Schnorrer, F. Mechanical forces during muscle development. Mech. Dev. 2017, 144, 92–101.

- Bowman, W.; Todd, R.B. XXI. On the minute structure and movements voluntary muscle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1840, 130, 457–501.

- Sanes, J.R. The basement membrane/Basal lamina of skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 12601–12604.

- Rahimov, F.; Kunkel, L.M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying muscular dystrophy. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 201, 499–510.

- Sweeney, H.L.; Hammers, D.W. Muscle contraction. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a023200.

- Kallabis, S.; Abraham, L.; Müller, S.; Dzialas, V.; Türk, C.; Wiederstein, J.L.; Bock, T.; Nolte, H.; Nogara, L.; Blaauw, B.; et al. High-throughput proteomics fiber typing (ProFiT) for comprehensive characterization of single skeletal muscle fibers. Skelet. Muscle 2020, 10, 7.

- Jakobsen, J.R.; Mackey, A.L.; Knudsen, A.B.; Koch, M.; Kjær, M.; Krogsgaard, M.R. Composition and adaptation of human myotendinous junction and neighboring muscle fibers to heavy resistance training. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 1547–1559.

- Jackman, R.W.; Kandarian, S.C. The molecular basis of skeletal muscle atrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C834–C843.

- Cohen, S.; Brault, J.J.; Gygi, S.P.; Glass, D.J.; Valenzuela, D.M.; Gartner, C.; Latres, E.; Goldberg, A.L. During muscle atrophy, thick, but not thin, filament components are degraded by MuRF1-dependent ubiquitylation. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 185, 1083–1095.

- Jackson, M.J. Reactive oxygen species in sarcopenia: Should we focus on excess oxidative damage or defective redox signalling? Mol. Aspects Med. 2016, 50, 33–40.

- Damiano, S.; Muscariello, E.; La Rosa, G.; Di Maro, M.; Mondola, P.; Santillo, M. Dual Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Muscle Function: Can Antioxidant Dietary Supplements Counteract Age-Related Sarcopenia? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3815.

- Ji, L.L. Redox signalling in skeletal muscle: Role of aging and exercise. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2015, 39, 352–359.

- Halliwell, B.; Cross, C.E. Oxygen-derived species: Their relation to human disease and environmental stress. Environ. Health Perspect. 1994, 102 (Suppl. S10), 5–12.

- Kehrer, J.P. The Haber-Weiss reaction and mechanisms of toxicity. Toxicology 2000, 149, 43–50.

- Castro, J.P.; Jung, T.; Grune, T.; Almeida, H. Actin carbonylation: From cell dysfunction to organism disorder. J. Proteomics 2013, 92, 171–180.

- Orient, A.; Donkó, A.; Szabó, A.; Leto, T.L.; Geiszt, M. Novel sources of reactive oxygen species in the human body. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2007, 22, 1281–1288.

- Burton, G.J.; Jauniaux, E. Oxidative stress. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 25, 287–299.

- Cadenas, E.; Davies, K.J. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 29, 222–230.

- Tu, B.P.; Weissman, J.S. Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: Mechanisms and consequences. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 164, 341–346.

- He, L.; He, T.; Farrar, S.; Ji, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, X. Antioxidants maintain cellular redox homeostasis by elimination of reactive oxygen species. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 532–553.

- Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I.; Witkowska, A.M.; Zujko, M.E. Endogenous non-enzymatic antioxidants in the human body. Adv. Med. Sci. 2018, 63, 68–78.

- Powers, S.K.; Jackson, M.J. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1243–1276.

- Marinho, H.S.; Real, C.; Cyrne, L.; Soares, H.; Antunes, F. Hydrogen peroxide sensing, signalling and regulation of transcription factors. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 535–562.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Vikash, V.; Ye, Q.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; Dong, W. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signalling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 4350965.

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: A concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183.

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748.

- Sai, K.K.S.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Zhu, C.; Shukla, K.; Forshaw, T.E.; Wu, H.; Vance, S.A.; Pathirannahel, B.L.; Madonna, M.; et al. Fluoro-DCP, a first generation PET radiotracer for monitoring protein sulfenylation in vivo. Redox Biol. 2022, 49, 102218.

- Olowe, R.; Sandouka, S.; Saadi, A.; Shekh-Ahmad, T. Approaches for Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress Quantification in Epilepsy. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 990.

- Oswald, M.C.W.; Garnham, N.; Sweeney, S.T.; Landgraf, M. Regulation of neuronal development and function by ROS. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 679–691.

- Jackson, M.J. Redox regulation of muscle adaptations to contractile activity and aging. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2015, 119, 163–171.

- Trinity, J.D.; Broxterman, R.M.; Richardson, R.S. Regulation of exercise blood flow: Role of free radicals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 98, 90–102.

- Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Aparicio-Trejo, O.E.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Mitochondrial Redox Signalling and Oxidative Stress in Kidney Diseases. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1144.

- Irazabal, M.V.; Torres, V.E. Reactive oxygen species and redox signalling in chronic kidney disease. Cells 2020, 9, 1342.

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4777.

- Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends Mol. Med. 2004, 10, 549–557.

- Baird, L.; Yamamoto, M. The Molecular Mechanisms Regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 Pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 40, e00099-20.

- He, F.; Antonucci, L.; Karin, M. NRF2 as a regulator of cell metabolism and inflammation in cancer. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 405–416.

- Foreman, N.A.; Hesse, A.S.; Ji, L.L. Redox Signalling and Sarcopenia: Searching for the Primary Suspect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9045.

- Li, Y.P.; Schwartz, R.J.; Waddell, I.D.; Holloway, B.R.; Reid, M.B. Skeletal muscle myocytes undergo protein loss and reactive oxygen-mediated NF-kappaB activation in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha. Faseb. J. 1998, 12, 871–880.

- Russell, S.T.; Eley, H.; Tisdale, M.J. Role of reactive oxygen species in protein degradation in murine myotubes induced by proteolysis-inducing factor and angiotensin II. Cell. Signal. 2007, 19, 1797–1806.

- Reid, M.B.; Li, Y.P. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and muscle wasting: A cellular perspective. Respir. Res. 2001, 2, 269–272.

- Li, Y.P.; Reid, M.B. NF-kappaB mediates the protein loss induced by TNF-alpha in differentiated skeletal muscle myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000, 279, R1165–R1170.

- Pedersen, M.; Bruunsgaard, H.; Weis, N.; Hendel, H.W.; Andreassen, B.U.; Eldrup, E.; Dela, F.; Pedersen, B.K. Circulating levels of TNF-alpha and IL-6-relation to truncal fat mass and muscle mass in healthy elderly individuals and in patients with type-2 diabetes. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2003, 124, 495–502.

- El Assar, M.; Angulo, J.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Frailty as a phenotypic manifestation of underlying oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 149, 72–77.

- Carmeli, E.; Coleman, R.; Reznick, A.Z. The biochemistry of aging muscle. Exp. Gerontol. 2002, 37, 477–489.

- Morley, J.E.; Thomas, D.R.; Wilson, M.M. Cachexia: Pathophysiology and clinical relevance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 735–743.

- von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.D. Prevalence, incidence and clinical impact of cachexia: Facts and numbers-update 2014. J. Cachex- Sarcopenia Muscle 2014, 5, 261–263.

- Johnson, C.A.; Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Levin, A.; Lau, J.; Eknoyan, G. Clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease in adults: Part I. Definition, disease stages, evaluation, treatment, and risk factors. Am. Fam. Physician 2004, 70, 869–876.

- Workeneh, B.T.; Rondon-Berrios, H.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Z.; Ayehu, G.; Ferrando, A.; Kopple, J.D.; Wang, H.; Storer, T.; Fournier, M.; et al. Development of a diagnostic method for detecting increased muscle protein degradation in patients with catabolic conditions. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 3233–3239.

- Milan, G.; Romanello, V.; Pescatore, F.; Armani, A.; Paik, J.-H.; Frasson, L.; Seydel, A.; Zhao, J.; Abraham, R.; Goldberg, A.L.; et al. Regulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin–proteasome system by the FoxO transcriptional network during muscle atrophy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6670.

- Diesel, W.; Emms, M.; Knight, B.K.; Noakes, T.D.; Swanepoel, C.R.; van Zyl Smit, R.; Kaschula, R.O.; Sinclair-Smith, C.C. Morphologic features of the myopathy associated with chronic renal failure. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1993, 22, 677–684.

- Deleaval, P.; Luaire, B.; Laffay, P.; Jambut-Cadon, D.; Stauss-Grabo, M.; Canaud, B.; Chazot, C. Short-term effects of branched-chain amino acids-enriched dialysis fluid on branched-chain amino acids plasma level and mass balance: A randomized cross-over study. J. Ren. Nutr. 2020, 30, 61–68.

- Martins, A.M.; Rodrigues, J.C.D.; de Oliveira Santin, F.G.; Brito, F.D.S.B.; Moreira, A.S.B.; Lourenço, R.A.; Avesani, C.M. Food intake assessment of elderly patients on hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 2015, 25, 321–326.

- Pike, M.; Taylor, J.; Kabagambe, E.; Stewart, T.G.; Robinson-Cohen, C.; Morse, J.; Akwo, E.; Abdel-Kader, K.; Siew, E.D.; Blot, W.J.; et al. The association of exercise and sedentary behaviours with incident end-stage renal disease: The Southern Community Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030661.

- Wang, X.H.; Mitch, W.E. Mechanisms of muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2014, 10, 504–516.

- Ikizler, T.A.; Pupim, L.B.; Brouillette, J.R.; Levenhagen, D.K.; Farmer, K.; Hakim, R.M.; Flakoll, P.J. Hemodialysis stimulates muscle and whole body protein loss and alters substrate oxidation. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2002, 282, E107–E116.

- Pupim, L.B.; Flakoll, P.J.; Brouillette, J.R.; Levenhagen, D.K.; Hakim, R.M.; Ikizler, T.A. Intradialytic parenteral nutrition improves protein and energy homeostasis in chronic hemodialysis patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 483–492.

- Pupim, L.B.; Majchrzak, K.M.; Flakoll, P.J.; Ikizler, T.A. Intradialytic oral nutrition improves protein homeostasis in chronic hemodialysis patients with deranged nutritional status. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 3149–3157.

- Carrero, J.J.; Stenvinkel, P.; Cuppari, L.; Ikizler, T.A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kaysen, G.; Mitch, W.E.; Price, S.R.; Wanner, C.; Wang, A.Y.; et al. Etiology of the protein-energy wasting syndrome in chronic kidney disease: A consensus statement from the International Society of Renal Nutrition and Metabolism (ISRNM). J. Ren. Nutr. 2013, 23, 77–90.

- Stenvinkel, P.; Larsson, T.E. Chronic kidney disease: A clinical model of premature aging. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 62, 339–351.

- Stel, V.S.; Brück, K.; Fraser, S.; Zoccali, C.; Massy, Z.A.; Jager, K.J. International differences in chronic kidney disease prevalence: A key public health and epidemiologic research issue. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32 (Suppl. S2), ii129–ii135.

- Biolo, G.; Fleming, R.Y.; Maggi, S.P.; Nguyen, T.T.; Herndon, D.N.; Wolfe, R.R. Inhibition of muscle glutamine formation in hypercatabolic patients. Clin. Sci. 2000, 99, 189–194.

- Gore, D.; Jahoor, F. Deficiency in Peripheral Glutamine Production in Pediatric Patients With Burns. J. Burn. Care Rehabil. 2000, 21, 171, discussion 172–177.

- Lightfoot, A.; McArdle, A.; Griffiths, R.D. Muscle in defence. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37 (Suppl. S10), S384–S390.

- Thome, T.; Salyers, Z.R.; Kumar, R.A.; Hahn, D.; Berru, F.N.; Ferreira, L.F.; Scali, S.T.; Ryan, T.E. Uremic metabolites impair skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics through disruption of the electron transport system and matrix dehydrogenase activity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 317, C701–C713.

- Thome, T.; Kumar, R.A.; Burke, S.K.; Khattri, R.B.; Salyers, Z.R.; Kelley, R.C.; Coleman, M.D.; Christou, D.D.; Hepple, R.T.; Scali, S.T.; et al. Impaired muscle mitochondrial energetics is associated with uremic metabolite accumulation in chronic kidney disease. JCI Insight 2020, 6, e139826.

- Duranton, F.; Cohen, G.; De Smet, R.; Rodriguez, M.; Jankowski, J.; Vanholder, R.; Argiles, A. Normal and pathologic concentrations of uremic toxins. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1258–1270.

- Vanholder, R.; Schepers, E.; Pletinck, A.; Nagler, E.V.; Glorieux, G. The uremic toxicity of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate: A systematic review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 1897–1907.

- Enoki, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Arake, R.; Sugimoto, R.; Imafuku, T.; Tominaga, Y.; Ishima, Y.; Kotani, S.; Nakajima, M.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Indoxyl sulfate potentiates skeletal muscle atrophy by inducing the oxidative stress-mediated expression of myostatin and atrogin-1. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32084.

- Rodrigues, G.G.C.; Dellê, H.; Brito, R.B.O.; Cardoso, V.O.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Cunha, R.S.; Stinghen, A.E.M.; Dalboni, M.A.; Barreto, F.C. Indoxyl Sulfate Contributes to Uremic Sarcopenia by Inducing Apoptosis in Myoblasts. Arch. Med. Res. 2020, 51, 21–29.

- Higashihara, T.; Nishi, H.; Takemura, K.; Watanabe, H.; Maruyama, T.; Inagi, R.; Tanaka, T.; Nangaku, M. β2-adrenergic receptor agonist counteracts skeletal muscle atrophy and oxidative stress in uremic mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9130.

- Sriram, S.; Subramanian, S.; Sathiakumar, D.; Venkatesh, R.; Salerno, M.S.; McFarlane, C.D.; Kambadur, R.; Sharma, M. Modulation of reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle by myostatin is mediated through NF-κB. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 931–948.

- Powers, S.K.; Kavazis, A.N.; DeRuisseau, K.C. Mechanisms of disuse muscle atrophy: Role of oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 288, R337–R344.

- Zhang, L.; Pan, J.; Dong, Y.; Tweardy, D.J.; Dong, Y.; Garibotto, G.; Mitch, W.E. Stat3 activation links a C/EBPδ to myostatin pathway to stimulate loss of muscle mass. Cell Metabol. 2013, 18, 368–379.

- Viana, J.L.; Kosmadakis, G.C.; Watson, E.L.; Bevington, A.; Feehally, J.; Bishop, N.C.; Smith, A.C. Evidence for anti-inflammatory effects of exercise in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 2121–2130.

- Ling, X.C.; Kuo, K.-L. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Ren. Replace. Ther. 2018, 4, 53.

- Mahdy, M.A.A. Skeletal muscle fibrosis: An overview. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 375, 575–588.

- Avin, K.G.; Chen, N.X.; Organ, J.M.; Zarse, C.; O’Neill, K.; Conway, R.G.; Konrad, R.J.; Bacallao, R.L.; Allen, M.R.; Moe, S.M. Skeletal muscle regeneration and oxidative stress are altered in chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159411.

- Uezumi, A.; Fukada, S.-I.; Yamamoto, N.; Takeda, S.I.; Tsuchida, K. Mesenchymal progenitors distinct from satellite cells contribute to ectopic fat cell formation in skeletal muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 143–152.

- Li, Y.; Huard, J. Differentiation of muscle-derived cells into myofibroblasts in injured skeletal muscle. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 161, 895–907.

- Ahmad, K.; Shaikh, S.; Ahmad, S.S.; Lee, E.J.; Choi, I. Cross-talk between extracellular matrix and skeletal muscle: Implications for myopathies. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 142.

- Csapo, R.; Gumpenberger, M.; Wessner, B. Skeletal muscle extracellular matrix—What do we know about its composition, regulation, and physiological roles? A narrative review. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 253.

- Dong, J.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Z.; Mitch, W.E.; Zhang, L. The pathway to muscle fibrosis depends on myostatin stimulating the differentiation of fibro/adipogenic progenitor cells in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 119–128.

- Snijders, T.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J. The impact of sarcopenia and exercise training on skeletal muscle satellite cells. Ageing Res. Rev. 2009, 8, 328–338.

- Fry, C.S.; Lee, J.D.; Jackson, J.R.; Kirby, T.J.; Stasko, S.A.; Liu, H.; Dupont-Versteegden, E.E.; McCarthy, J.J.; Peterson, C.A. Regulation of the muscle fiber microenvironment by activated satellite cells during hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1654–1665.

- Abramowitz, M.K.; Paredes, W.; Zhang, K.; Brightwell, C.R.; Newsom, J.N.; Kwon, H.-J.; Custodio, M.; Buttar, R.S.; Farooq, H.; Zaidi, B.; et al. Skeletal muscle fibrosis is associated with decreased muscle inflammation and weakness in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2018, 315, F1658–F1669.

- Baker, L.A.; O’Sullivan, T.F.; Robinson, K.A.; Graham-Brown, M.P.M.; Major, R.W.; Ashford, R.U.; Smith, A.C.; Philp, A.; Watson, E.L. Primary skeletal muscle cells from chronic kidney disease patients retain hallmarks of cachexia in vitro. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1238–1249.

- Ryall, J.G.; Schertzer, J.D.; Lynch, G.S. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness. Biogerontology 2008, 9, 213–228.

- Yue, Z.; Mester, J. A model analysis of internal loads, energetics, and effects of wobbling mass during the whole-body vibration. J. Biomech. 2002, 35, 639–647.

- Suhr, F. Extracellular matrix, proteases and physical exercise. Dtsch. Z. Für Sportmed. 2019, 70, 97–104.

- Leal, V.O.; Saldanha, J.F.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; Cardozo, L.F.M.F.; Santos, F.R.; Albuquerque, A.S.D.; Leite, M., Jr.; Mafra, D. NRF2 and NF-κB mRNA expression in chronic kidney disease: A focus on nondialysis patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2015, 47, 1985–1991.

- Pedruzzi, L.M.; Cardozo, L.F.M.F.; Daleprane, J.B.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B.; Monteiro, E.B.; Leite, M.; Vaziri, N.D.; Mafra, D. Systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in hemodialysis patients are associated with down-regulation of Nrf2. J. Nephrol. 2015, 28, 495–501.

- Nezu, M.; Suzuki, N.; Yamamoto, M. Targeting the KEAP1-NRF2 System to Prevent Kidney Disease Progression. Am. J. Nephrol. 2017, 45, 473–483.

- Wang, J.; Zhu, H.; Huang, L.; Zhu, X.; Sha, J.; Li, G.; Ma, G.; Zhang, W.; Gu, M.; Guo, Y. Nrf2 signalling attenuates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and renal interstitial fibrosis via PI3K/Akt signalling pathways. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2019, 111, 104296.

- Panizo, S.; Barrio-Vázquez, S.; Naves-Díaz, M.; Carrillo-López, N.; Rodríguez, I.; Fernández-Vázquez, A.; Valdivielso, J.M.; Thadhani, R.; Cannata-Andía, J.B. Vitamin D receptor activation, left ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 2735–2744.

- Mann, C.J.; Perdiguero, E.; Kharraz, Y.; Aguilar, S.; Pessina, P.; Serrano, A.L.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Aberrant repair and fibrosis development in skeletal muscle. Skelet. Muscle 2011, 1, 21.

- Mallamaci, F.; Pisano, A.; Tripepi, G. Physical activity in chronic kidney disease and the EXerCise Introduction To Enhance trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35 (Suppl. S2), ii18–ii22.

More