1. Molecular Mechanism of ER

1.1. Genomic Action

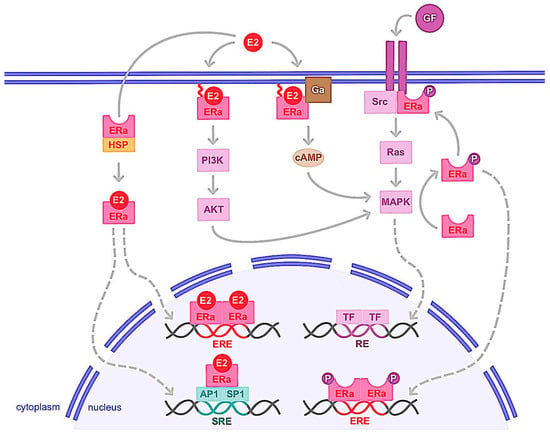

ERα is a transcription factor regulating the expression of genes involved in cell cycles, proliferation and apoptosis. Indeed, activation of ERα allows the expression of factors such as MYC, Cyclin D1, FOXM1, GREB1, BCL2 or amphiregulin, IGF-1 and CXCL12, which have oncogenic potential, increasing cancer cells proliferation and the risk of DNA damage in response to the estrogens

[1][9]. Once estrogen (E2) is bound to ERα, it allows the receptor to change its conformation in an active form, dimerize, translocate to the nucleus and interact with transcriptional coactivators (

Figure 13). It is of note that unlike E2, antagonistic molecules such as tamoxifen induce inactive conformation of ERα, which recruit transcriptional corepressors

[2][51]. Ligand-activated ERα then binds to estrogen-responsive elements (EREs) within the promoters of target genes. ERα can also interact with transcription factors, such as activator protein 1 (AP1) and specific protein 1 (SP1) via serum responsive elements (SREs) to regulate genes lacking ERE in their promoters (

Figure 13). This genomic action thus regulates the transcription of hundreds of target genes involved in cell growth and differentiation

[3][4][5][52,53,54]. The deregulation of ERα expression, activity or its coregulators and target genes then plays a prominent role in the development of the majority of breast cancers, known as ERα+ or luminal. It should be noted that the two other receptors, ERβ and GPER, can be stimulated by estrogens. ERβ is a nuclear receptor homologous to ERα, encoded by the ESR2 gene and with a structure similar to ERα

[6][55]. Like ERα, ERβ is expressed in many reproductive organs such as mammary epithelial cells, ovaries, uterus and testes, as well as non-reproductive organs, such as lungs, adrenal or adipose tissue or brain. This receptor interacts with some ERα transcriptional coregulators and shares ligands similar to ERα, such as estrogens and SERMs (selective estrogen receptor modulators), but with different affinity. In contrast to ERα, activation of ERβ generally results in inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis, but these effects depend on the tissue studied, the cell context, transcriptional coactivators, and whether ERα is coexpressed

[6][55]. ERβ expression in breast tumor cells then tends to correlate with a favorable prognosis, but some studies indicate the opposite. Indeed, previous studies indicate that ERβ and its isoforms as well as certain coactivators such as AIB1, NF-kB and TIF-2 tend to coregulate breast cancer cell proliferation and progression

[7][8][56,57]. These specific coactivators are associated with poor clinical outcomes and were correlated with high ERβ expression in high-grade breast tumor subtypes, suggesting that they may mediate ERβ proliferation in breast cancer cells

[9][58]. Thus, further work remains necessary to better understand the physiological role of this receptor and its involvement in breast carcinoma

[10][11][59,60].

Figure 13. Genomic and non-genomic activities of ERα. ERα activation upon estrogen binding (E2) or after its phosphorylation (P) by cellular kinases following growth factor (GF) receptor stimulation leads to its translocation into the nucleus. There, ERα homodimer binds DNA either directly or indirectly, through estrogen responsive elements (EREs), or upon binding to other transcription factors such as AP1 or SP1 that bind DNA through serum responsive elements (SREs). This is the so-called genomic action of ERα which leads to the regulation of the transcription of target genes. ERα can also be anchored to the membrane and interacting with G proteins (Ga) or GF receptors. ERα activation is then implicated in second messenger production (cyclic adenosine monophosphate, cAMP) and signaling pathways stimulation involving PI3K/AKT or Ras/MAPK for example. This nongenomic activity of ERα eventually leads to transcription factors (TFs) activation involved in the regulation of cell proliferation and survival. cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; E2: estrogen; ERα: estrogen receptor alpha; ERE: estrogen responsive element; Ga: G alpha protein; GF: growth factor; HSP: heat shock protein; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; P: phosphate; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; SRE: serum responsive element.

Both ligand-dependent and -independent activation of ERα have been reported

[12][13][61,62]. ERα is the target of numerous post-translational modifications that are crucial for the regulation of ligand- independent ERα and may affect its stability, dimerization, subcellular localization, DNA binding or interaction with cofactors

[14][63]. In particular, phosphorylation of ERα following activation of certain intracellular kinases by growth factors is a key mechanism of ligand-independent activation of ERα

[15][16][17][64,65,66]. Notably, phosphorylation of serine residues 118 (S118), S167, S305 and tyrosine 537 (Tyr537) increases ERα activity through interactions with coactivators in breast cancer cells

[17][18][19][20][21][22][66,67,68,69,70,71]. ERα is also acetylated at different lysine residues by the acetylase p300. Interestingly, acetylation of lysine 266/268 stimulates ER transcriptional activity, while acetylation of lysine 302/303 inhibits ERα activity

[23][72].

1.2. Nongenomic Action

The interplay between growth factors such as EGF or IGF and sex steroid (estrogen or androgen) signaling has been previously analyzed at different levels

[24][25][73,74]. Indeed, in addition to its translocation into the nucleus and its function as a genomic pathway transcription factor, a small proportion of cytosolic or membrane-anchored ERα also rapidly and transiently exerts non-genomic activity

[26][27][75,76]. This involves the rapid activation of intracellular signaling pathways including cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate) production or the activation of growth factor receptors, PI3K/AKT or Ras/MAPK pathways (

Figure 13). Upon E2 binding, ERα rapidly forms a cytoplasmic complex with several proteins including the Src protein kinase and the p85 subunit of PI3K, triggering the MAPK and Akt pathways after only 2 to 15 min of ligand binding

[28][29][30][77,78,79]. The mechanisms of ERα addressing the plasma membrane and its non-genomic activity are based on post-translational modifications. For example, palmitoylation of cysteine 447 of human ERα is essential. The binding of palmitate to this residue increases the hydrophobicity of the receptor and its anchoring to the caveolae which are regions of the plasma membrane enriched in cholesterol

[31][80]. Interestingly, this association of ERα with caveolin-1 in the plasma membrane triggers non-genomic signaling pathways, activation of cyclin D1 and cell proliferation

[31][32][33][80,81,82]. Furthermore, Le romancer et al.

[34][83] demonstrated that methylation of ERα on arginine 260 by the arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 is required for the interaction of ERα with Src and p85 partners and thus the stabilization of the estrogen-induced ERα/Src/p85 complex. in addition, Src and PI3K activity is essential for ERα methylation and thus for ERα/Src/p85 association and downstream Akt activation

[14][35][36][63,84,85]. It is also noteworthy that ERα methylation occurs only 5 to 15 min after ligand stimulation

[14][63]. Note also that IGF-1 causes rapid methylation of ERα by PRMT1 and triggers ERα binding to the IGF-1 receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Interestingly, IGF-1 receptor expression was found to be positively correlated with ERα/Src and ERα/PI3K interaction in a cohort of breast tumors

[35][36][84,85]. On the other hand, phosphorylation of Tyr537 of ERα plays a key role in the interaction of ERα with Src kinase, activation of the MAPK pathway and cell proliferation

[37][86].

GPER, a seven transmembrane domain protein, that can trigger rapid cellular effects of estrogen

[38][87], is also expressed in different organs such as liver and adipose tissue in addition to the mammary gland

[39][88]. GPER expression has also been reported in several types of breast cancer cells

[40][89]. Its stimulation by estrogen increases cAMP concentrations and the mobilization of intracellular calcium

[41][42][90,91]. This also results in the activation of signaling cascades such as PI3K/AKT and Ras/MAPK, ultimately regulating the transcription of genes for cell proliferation and survival

[43][44][92,93]. These genes include c-fos, cyclin D, B and A which are involved in the cell cycle and promote cell proliferation. They are induced by GPER while other genes such as BAX, caspase 3 and BCL2, involved in the process of cell apoptosis, are downregulated by GPER

[45][46][47][48][94,95,96,97]. In a mouse xenograft model of breast cancer, GPER activation increases tumor growth and expression of HIF1, VEGF, and the endothelial marker CD34

[49][98]. Conversely, in this model, the use of a GPER inhibiting peptide exerts apoptosis and induces a significant decrease in the size of triple-negative mammary tumors in mice

[50][99]. Activation of the membrane receptor GPER would then appear to have a pro-tumor effect and could play a role in the acquisition of resistance to hormone therapy, with SERMs acting as agonists of this receptor

[51][52][53][100,101,102]. In fact, tamoxifen exerts an agonist effect by inducing gene expressions involved in breast tumorigenesis

[51][54][100,103]. Moreover, in ERα-positive patients receiving tamoxifen treatment, the presence of GPER strongly correlated with worse relapse-free survival

[47][49][96,98]. However, as for ERβ, further work is needed to better identify the functions of this receptor and consider it as a therapeutic target in breast cancer

[55][104].

The nuclear and membrane-initiated pathways of ERα should not be completely dissociated. Indeed, there is a possibility of dialogue between genomic and non-genomic actions. One way in which these two major ERα pathways are connected is through phosphorylation of ERα or its cofactors

[56][57][58][105,106,107]. For example, E2-mediated transcriptional activation of cyclin D1 via the AP-1 binding site requires MAPK activity and formation of an ERα/Src/PI3K complex

[57][58][106,107], indicating that there is a convergence of genomic and non-genomic signaling on E2 target genes

[59][108]. However, previous studies have suggested that the non-genomic action of ERα may be associated with resistance to endocrine therapy and poor prognosis in breast cancer

[35][60][61][84,109,110].

DWe also showed that during cancer progression, a transition to the monomeric state of ERα induces a decrease in the genomic activity of ERα and promotes its non-genomic activity

[62][111].

2. ERα Variants and Mutations

In addition to the full-length ERα which represents a 66 kDa protein, two major variants of lower molecular weight, ERα 46 kDa and ERα 36 kDa, have been identified

[63][64][65][66][67][68][112,113,114,115,116,117]. These variants which originate from alternative splicing, have been detected in healthy and cancerous breast tissues, as well as in various breast cancer cell lines

[67][69][70][116,118,119]. The ERα46 isoform differs from the full-length ERα66 only in the absence of the N-terminal activation function 1 (AF-1), whereas the ERα36 isoform, lacks both transactivation domains, AF-1 and AF-2, but conserves the DNA-binding domain and a part of ligand-binding domains

[63][67][112,116]. The overall structure of ERα36 is identical to ERα46 except for a unique sequence of 27 amino acids in place of the last 138 amino acids in the C-terminus of ERα46 and ERα66. The two truncated isoforms, ERα46 and ERα36, show partially different activities than the classical ERα66, notably for ligand binding, transactivation, interaction with coregulators and subcellular localization

[64][68][71][113,117,120]. In particular, ERα36 is mainly located in the cytoplasm and at the plasma membrane and expressed in both ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer cells

[63][67][71][112,116,120]. This receptor is also able to bind to DNA and thus inhibit the genomic activity of ERα66. In the cytoplasm, it exerts a non-genomic activity in the presence of estrogens, allowing for the activation of multiple pathways, notably the MAPK pathway, which contribute to cancer aggressiveness and progression. ERα36 can also mediate the agonistic effects of tamoxifen and induce resistance to antiestrogens

[72][73][74][75][76][121,122,123,124,125]. However, further research is needed to fully identify the biological activities of these ERα variants and to determine whether they constitute a potential therapeutic target. Also of note is that evaluation of ER status in breast tumors is important to provide information on diagnosis and treatment choice. However, current methods using immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis have limitations and do not discriminate these ERα subtypes in the biopsies. Accurate characterization of these variants therefore requires specific antibodies for each of these isoforms.

Previous studies have shown that mutations on the ERα gene occur in less than 5% in primary tumors while they are significantly increased up to 50% in the metastatic-resistance tumors, especially in patients treated with aromatase inhibitors (AIs)

[77][126]. So far 62 mutations have been described for the ERα gene in tumor samples. Most of these mutations (47 out of 62) occur in the ERα ligand-binding- domain (LBD), and some of them make the receptor constitutively active

[78][127]. This suggests that these activating mutations of the ERα are only generated under the selective pressure of treatment with AIs and thus estrogen deprivation. Y537S and D538G are the two most common ERα mutations found in tumors. These mutations induce the receptor in its active conformation in the absence of ligand, enhance coactivator interactions with the receptor and strongly decrease its affinity for antiestrogens, tamoxifen and fulvestrant, indicating the importance of these mutations in the resistance to endocrine therapies. Also of note is a recent study on breast cancer cells, which showed that these ERα mutations induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promote the proliferation and invasion of cancer cells, in vitro and in vivo

[79][128].

3. Hormone Therapy and Resistance

Because two-thirds of breast cancer cell proliferation is dependent on estrogen activation of ERα, the treatment of choice is hormone therapy. This consists of depriving the tumor of estrogen or blocking the activity of ERα, thus preventing breast cancer recurrence and increasing the overall survival of patients. Of the ERα antagonists, tamoxifen, which belongs to the SERM family, is the best characterized and most clinically used

[80][129]. Unlike estrogen, tamoxifen binding to ERα induces corepressor recruitment which promotes the inhibition of breast cancer cell growth

[81][130]. A 5-year course of tamoxifen is the treatment of choice for premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Tamoxifen has long been the only treatment for more than 20 years for advanced breast cancer. However, in the late 1990s, the development of AIs significantly transformed first and second-line treatments. These active substances (letrozole, anastrozole or exemestane) with therapeutic effect inhibit the activity of the enzyme aromatase, which allows the conversion of androgens into estrogens

[82][131]. Indeed, while in premenopausal women most estrogen is produced by ovaries, in postmenopausal women aromatase, present in other tissues than the ovaries such as adipocyte and breast tissues, can lead to estrogen production which can favor tumor progression

[82][131]. In the early 2000s, a new family of therapeutically active substances was developed with fulvestrant, an ERα antagonist. This family includes SERDs (selective estrogen receptor degraders), which bind to ERα, causing its inactivation by degradation

[83][132], in contrast to SERMs, which are responsible for conformational modification of ERα by promoting the recruitment of co-repressors

[80][129]. The binding affinity of fulvestrant to the ERα is equivalent to that of E2 without agonist activity. The use of fulvestrant is generally reserved for luminal metastatic breast cancer, or for patients who have become resistant to a first hormone therapy with IAs or SERMs

[84][133]. Fulvestrant is used by intramuscular injection in postmenopausal women with then advanced tumors. However, new SERDs that can be prescribed orally are currently being developed and tested in clinical trials

[85][134].

In approximately 30% of ERα+ breast cancers, breast tumor cells may escape hormonal control, thereby acquiring the ability to proliferate in the absence of estrogen stimulation. Hormonal escape is typically accompanied by the loss of the epithelial phenotype and the gain of a more migratory and invasive capacity

[86][135]. Hormone therapy is then no longer effective in countering cancerous growth. This resistance is rarely due to a loss of ERα expression (only 10% of cases), but rather to a deregulation of the activation of this receptor, which can be stimulated independently of estrogen binding. Different mechanisms can lead to this ligand-independent activity, the most frequent alterations are (i) the acquisition of mutations rendering ERα constitutively active; (ii) epigenomic and post-translational changes in the ERα; (iii) the activation of ERα by oncogenic intracellular signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT, and Ras/MAPK as well as growth factors (EGFR, HER2, IGF1R, FGFR), which are themselves deregulated in cancer cells; (iv) an increase in the interaction of ERα with coactivators, at the expense of its corepressors

[86][135]. Indeed, high expression of coactivators such as AIB1 or low expression of corepressors such as NCOR1 is associated with poor clinical outcomes and is predictive of an unfavorable response to tamoxifen

[9][12][58,61].

For patients who have become resistant, one therapeutic approach is to target the signaling pathways involved in ligand-independent activation of ERα. For example, aberrations of the PI3K/AKT pathway are common in ERα-positive breast cancer and could play a crucial role in tumor resistance. It is thus possible to combine hormone therapy with inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT pathway such as alpelisib and everolimus

[87][43]. It is also possible to combine hormone therapy with inhibitors of CDK4/6 such as palbociclib, ribociclib, or of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors such as entinostat, vorinostat

[88][89][90][91][92][44,136,137,138,139]. Indeed, overexpression of cyclin D1, present in 50% of breast cancers, leads to CDK4/6 and ERα activations and cell cycle progression

[93][140]. Consequently, CDK4/6 inhibitors in combination with hormone therapies have become standard treatment choices for ERα-positive metastatic breast cancer

[94][141]. Also of note that the most common epigenetic changes during cancer progression are likely DNA methylation and histone acetylation. DNA demethylating compounds such as decitabine and 5-azacytidine and HDAC inhibitors may be able to re-sensitize endocrine-resistant ER+ breast cancer

[95][96][142,143]. In addition, the HDAC inhibitor, entinostat, also shows immunomodulatory action by enhancing immunocompetent monocytes, which leads to increased overall survival

[97][144]. Furthermore, clinical trials are underway to test the efficacy of different therapeutic combinations depending on the patient profile

[98][145]. Finally, it should be noted that ER and other steroid receptors are expressed in stem cells and may control the behavior of cancer stem cells that are, in part, responsible for treatment resistance and tumor recurrence

[99][146].