Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Several cardiovascular risk factors are implicated in atherosclerotic plaque promotion and progression and are responsible for the clinical manifestations of coronary artery disease (CAD), ranging from chronic to acute coronary syndromes and sudden coronary death. The advent of intravascular imaging (IVI), including intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography and near-infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy has significantly improved the comprehension of CAD pathophysiology and has strengthened the prognostic relevance of coronary plaque morphology assessment. Indeed, several atherosclerotic plaque phenotype and mechanisms of plaque destabilization have been recognized with different natural history and prognosis. Finally, IVI demonstrated benefits of secondary prevention therapies, such as lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory agents.

- coronary artery disease

- biological mechanisms

- intracoronary imaging

- plaque vulnerability

1. Introduction

2. Pathophysiology of Coronary Atherosclerotic Disease

2.1. Endothelial Function

The endothelium, a monolayer of cells located in the intima on the luminal side of the vessels, has a central role in vascular homeostasis that varies from the regulation of vessel wall permeability and vascular tone to the control of local thrombogenicity [9]. The endothelium is at first a selective barrier accomplished by negatively charged molecules constituting glycocalyx covering the endothelial cells (ECs) and by protein-binding complexes (i.e., tight junctions, adherens junctions and gap junctions) regulating molecules and cells translocation. ECs also act as secretory cells releasing different mediators, such as endothelin 1 (ET-1), nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin and angiotensin 2, acting as vasoactive regulators; adhesion molecules, such as vascular adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1); or growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor 1 (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). By interplaying with the surrounding vascular smooth muscle cells and blood circulating cells (such as platelets and white blood cells) through these mediators, ECs are able to regulate vascular tone, platelet function and cell permeability [10]. Finally, by providing a tissue factor and releasing thrombin inhibitors and receptors for protein C activation, ECs play a regulatory function of local thrombogenicity [9].2.2. Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation and Progression

Qualitative changes of the endothelial monolayer are essential for atherosclerosis [3][11][3,11]. Flow perturbation, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL), advanced glycation products and reactive oxygen species (ROS) can lead to an imbalance of ECs homeostasis, determining their activation and dysregulation. ECs activation produces an intracellular Nf-kB signaling cascade responsible for the increased cellular expression of adhesion molecules (e.g., VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and P-selectin); proinflammatory receptors production (Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2)); the release of chemokines (e.g., monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and interleukin-8) and prothrombotic factors, favoring lipoprotein and inflammatory cells’ translocation and retention; and a local prothrombogenic milieu [12]. Branch points, bifurcations and major curvatures, sites of flow perturbation, represent the areas more prone to atherosclerotic plaque development [10]. Atherogenesis begins with the accumulation of lipoproteins, in particular LDL in the subendothelial space [13][14][13,14]. In the inner intimal layer, oxidized LDL act as the chronic stimulators of innate and adaptive immune responses [11][15][11,15], while activated ECs and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) express adhesion molecules, chemoattractants and growth factors interacting with monocyte receptors, stimulating their homing, migration and differentiation into macrophages and dendritic cells [13]. In particular, macrophages in the intima phagocytose oxidized LDL through the scavenger receptors SR-A and CD36. Scavenger receptors are not downregulated by oxidized LDLs and the progressive heavy lipid engulfment by macrophages determine the formation lipid-laden macrophages, also called foam cells [9]. The accumulation of foam cell macrophages within the intima corresponds to histological intimal xanthoma or “fatty streaks” [2]. Macrophage polarization has been reported to be important in the atherosclerotic process. It has been demonstrated that the Notch cellular signaling may be able to control the differentiation of macrophages into M1 or M2 subtypes [10]. Pro-inflammatory polarized macrophages (M1-like phenotype), activated by TLR-2 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), contribute to ROS production and to the release of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β), enzymes (e.g., myeloperoxidase (MPO), cathepsins, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)) and plasminogen activators, amplifying local inflammation and LDL oxidation. It has been also recently suggested that oxidized LDL may activate TLR-4 pathways on macrophages, strongly implicated in atherogenesis together with TLR-2. Moreover, TLR-2 and TLR-4 activation has been suggested to be important in infection-related atherosclerosis [10]. Conversely, M2-like macrophage phenotype exhibits anti-inflammatory properties by releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines and by clearing apoptotic cells to prevent necrotic core formation [13][16][17][13,16,17]. As soon as the atherosclerotic process progresses, VSMCs undergo dedifferentiation, proliferation and migration from the media to the intima stimulated by the growth factors secreted by macrophages, producing constituents of extracellular matrix (ECM), such as collagen, elastin, proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycan. ECM is predisposed to ligate lipoproteins, favoring acellular lipid accumulation within the intima [18][20] and causing the transition from intimal xanthoma to pathological intimal thickening [2][13][2,13]. In the following phase, lipid-laden macrophages and VSMCs undergo apoptosis and secondary necrosis, determining the release of lipid droplets in the intima and the formation of lipid-rich core or “necrotic core”. The presence of necrotic core encapsulated by a fibrous cap denotes the plaque stage of fibroatheroma [2]. The defective efferocytosis of apoptotic macrophages and VSMCs is thought to contribute to necrotic core formation [16]; moreover, the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells may hamper apoptotic bodies removal, generating a self-holding loop increasing lipid deposition, necrotic core enlargement and further inflammation, accompanied by a progressive reduction in the expression of ECM. Plaque neo-angiogenesis, cholesterol clefts formation and plaque calcification may also occur in later stages [19][21]. Hypoxia induced by intimal thickening and plaque growth represents the main stimulus for plaque neo-angiogenesis, enabling cellular migration to the intima [20][22].2.3. Vulnerable Plaque

The term “vulnerable plaque” characterizes plaques at risk of acute coronary events causing luminal thrombosis. The thin cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) represents the prototype of a plaque prone to rupture, characterized by a sizeable necrotic core with an overlying thin fibrous cap (FC), the presence of macrophages and lymphocytes and reduced or absent VSMCs [2]. Increased neovascularization, IPH and calcification have been also described in this lesion. The TCFA has been found mainly in the proximal portion of major coronary arteries, in particular, in the left anterior descending coronary artery. In pathology studies, the TCFA was frequently found at the site of acute coronary thrombosis, causing sudden coronary death [7]. The size of necrotic core has been considered as an important risk factor for rupture, causing a greater tensile stress to the FC and promoting its fissuration [13]. Inflammation is also important for plaque vulnerability. Enhanced inflammatory processes may hamper the synthesis of interstitial collagen by VSMCs, prejudicing their ability to maintain FC structure [18][20], and may favor MMPs production, degrading the FC covering the necrotic core. Increased neo-angiogenesis and IPH causes plaque expansion, the accumulation of free cholesterol and increased oxidative stress and plaque inflammation [21][23].2.4. Mechanisms of Plaque Destabilization

Plaque rupture (PR), the most frequent cause of SCD related to intraluminal thrombosis [7], has been histologically characterized by the presence of thrombus over a thin disrupted FC with underlying lipid necrotic core and usual macrophages or T lymphocytes infiltration into the plaque [2]. At ruptured sites, ninety-five percent of lesions showed a cap thickness < 65 μm (μm), suggesting the aforementioned TCFA as precursor of PR [13][22][13,30]. An imbalance between ECM-degrading proteinases released by macrophages and the tissue inhibitors of MMP or the cystatins [23][31] may cause ECM breakdown and progressive cap thinning. Adaptive immune system dysregulation between proinflammatory Th1 and regulatory T cells towards the former has also been hypothesized to be important for plaque destabilization, as well as VSMC senescence and death driven by a reduced telomeric repeat-binding factor-2 expression [23][24][31,32]. PR has been also identified in the absence of systemic inflammation, suggesting that other possible mechanisms may be involved, such as emotional stress, physical characteristics, changes in environmental factors and local shear stress [25][26][27][28][18,33,34,35]. Finally, cholesterol crystallization has been described as being potentially responsible for plaque disruption and thrombosis [29][30][26,27]. After FC rupture, the exposition of the necrotic core and tissue factor determines the activation of coagulation cascade, generating intraluminal thrombus formation rich in erythrocytes, fibrin and platelets [13].2.5. Plaque Healing

Plaque healing represents a dynamic and step-by-step process, which occurs after plaque destabilization and intraluminal thrombosis [31][38]. Three main phases have been hypothesized in plaque healing: thrombus lysis, granulation tissue formation and a new layer of re-endothelization [8]. Fibrinolytic system activation is stimulated after plaque destabilization, with the aim to disaggregate fibrin and prevent occlusive thrombosis and consists of the release of tissue plasminogen activator and urokinase plasminogen activator from ECs and the secretion of elastase and cathepsin G from neutrophils and monocytes. Subsequently, medial VSMCs translocating into the intima undergo migration and activation [8][32][8,39], leading to ECM production, in particular proteoglycans and type III collagen, being progressively replaced by type I collagen together with the new layer re-endothelization to complete the healing process [8]. This process may eventually occur in repeated cycles, as suggested by previous histology and OCT studies demonstrating multiple layers of tissue in the same plaques [33][34][40,41], causing negative remodeling and progressive luminal narrowing. Detailed mechanisms regulating plaque healing are unknown, although inflammation through macrophage M2-like phenotypes triggered by Th2 lymphocytes, has been hypothesized to play a role in the healing process [8].3. Relationship between Pathophysiology and Imaging Features

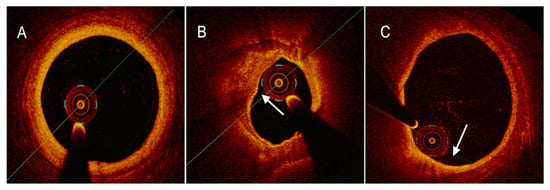

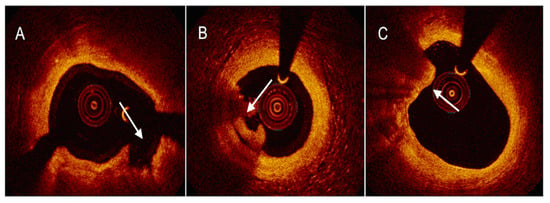

FC, predominantly composed by ECM and VSMCs, is implicated in plaque stability [18][20]. The thinning of the FC is a sign of plaque transition from a stable to a vulnerable phenotype [13]. OCT is the most reliable tool for assessing FC thickness, thanks to its high spatial resolution [35][51]. Macrophage infiltration is the hallmark of plaque inflammation. Macrophages release a plethora of cytokines, contributing to local proinflammatory microenvironment and infiltrating the FC, thus leading to the degradation of the ECM [10][18][10,20]. OCT is capable of detecting the presence and the density of intraplaque macrophages depicted as signal-rich distinct or confluent punctate regions that exceed the intensity of background speckle noise [35][51]. The necrotic core encompasses apoptotic and necrotic foam cells along with inflammatory cells and is a major determinant of plaque vulnerability [13][16][13,16]. The extent of necrotic core can be assessed by available intracoronary techniques, labelled as hypoechoic regions by IVUS [36][52], as signal-poor regions diffusely bordered by OCT [35][51] and as yellow-signal structures by NIRS [37][53]. Intracoronary microcalcifications result from the aggregation of calcifying extracellular vesicles and microcalcific deposits in the context of an inflamed microenvironment with a large necrotic core [13]. Microcalcifications act as mechanical stressors leading to plaque instability [30][27]. The low IVUS axial resolution precludes the adequate visualization of microcalcifications [36][52], while OCT is capable of assessing calcium arc and depth, labelled as signal-poor regions with sharply delineated borders [35][51].4. Role of Intravascular Imaging

The advent of IVI represented a milestone in the appraisal of CAD, allowing the diagnostic capacity of coronary angiography to be overcome in manifold clinical contexts: the elucidation of ambiguous lesions, the in vivo characterization of atherosclerotic plaque phenotype and the mechanisms of plaque destabilization, the guidance of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and the identification of mechanisms of PCI failure [36][52].4.1. Intravascular Ultrasound

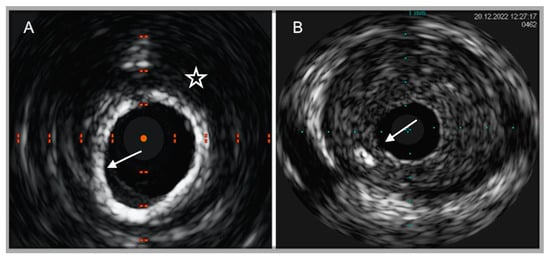

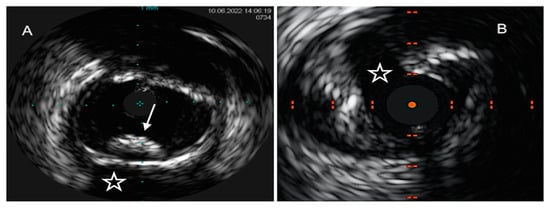

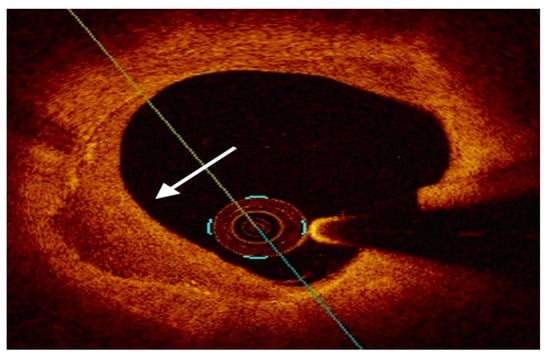

IVUS was the first IVI technique introduced into the clinical setting more than thirty years ago. The IVUS system consists of a sound probe located at the distal part of a dedicated catheter, emitting high-frequency sound waves from 20 to 60 MHz. Through the densitometric quantitative analysis of ultrasound signals, IVUS offers a real-time monochrome cross-sectional image of the full circumference of the coronary artery wall and atherosclerotic plaques. A major limitation of IVUS lies in the insufficient discrimination between lipidic and fibrolipidic plaques and in the flawed evaluation of tissues with overhanging superficial macrocalcification [38][54]. Virtual-histology IVUS (VH-IVUS), by means of radiofrequency ultrasound backscatter data and a color-coded map, was able to overcome these pitfalls, leading to a classification of coronary atherosclerotic plaques into four phenotypes with high diagnostic accuracy as compared to matched histopathological results: calcified and fibrous plaques are recognized as hyperechoic and homogenous structures, marked in white and green, respectively, on the color-coded map, while lipidic and mixed/fibro-fatty plaques were labeled as low-density regions, with a red and yellow appearance, respectively [39][55] (Figure 1).

4.2. Optical Coherence Tomography

4.3. Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy

NIRS is a novel imaging tool that leverages electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths from 800 to 2.500 nm and the property of tissues to differently absorb and scatter NIR light. By chemically interrogating coronary plaques, NIRS is the gold standard technique used to detect intraplaque lipid content, reported as a numerical lipid-core burden index (maxLCBI4mm) [37][53]. First-generation NIRS was hindered by low penetration power and high rates of non-interpretable images. Recently, two dual-system technologies (TVC Imaging System TM and Makoto intravascular Imaging System TM, Infraredx Inc) have allowed these limitations to be overcome by incorporating a scanning NIR laser and a traditional IVUS-sized catheter. NIRS technology outputs a chemogram, which displays the longitudinal view of the coronary artery on the x-axis and the circumferential location within the vessel on the y-axis. Lipid segments are colored yellow, while the remaining plaque components are labelled as red signals [50][51][79,80].

The pivotal COLOR [52][81] and CANARY (Coronary Assessment by Near-Infrared of Atherosclerotic Rupture-prone Yellow) [53][82] registries established the diagnostic accuracy of NIRS-IVUS technology in identifying LRP, while Terada et al. confirmed its ability to detect the mechanisms of plaque destabilization in a population of 244 STEMI patients. In this latest study, as compared to OCT, the NIRS-IVUS system demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 97% and 96% for identifying OCT-PR, 93% and 99% for OCT-PE and 100% and 99% for OCT-CN, respectively [54][83].

Finally, the NIRS-IVUS strategy was adopted to answer the question of whether stenting vulnerable non-flow limiting coronary plaques might decrease the occurrence of future MACEs. The PROSPECT ABSORB study was a randomized trial comparing coronary revascularization with bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) versus optimal medical therapy in cases of vulnerable NCL. In the study, at a 25-month follow-up, BVS-strategy significantly enlarged MLA at target site along with a lower occurrence of episodes of severe angina, without differences in terms of hard endpoints [55][93].