Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Hosam M. Saleh.

Carbon capture and use may provide motivation for the global problem of mitigating global warming from substantial industrial emitters. Captured CO

2

may be transformed into a range of products such as methanol as renewable energy sources. Polymers, cement, and heterogeneous catalysts for varying chemical synthesis are examples of commercial goods. Because some of these components may be converted into power, CO

2

is a feedstock and excellent energy transporter. By employing collected CO

2

from the atmosphere as the primary hydrocarbon source, a carbon-neutral fuel may be created. The fuel is subsequently burned, and CO

2

is released into the atmosphere like a byproduct of the combustion process.

- carbon capture

- CO2

- renewable energy

- global warming

1. Introduction

Global carbon emissions fell 5% in the first quarter of 2020 compared to the first half of 2019, owing to lower coal consumption (8%), oil (4.5%), and natural gases (2.3 percent). Another paper provided the daily, monthly, and annual rhythms of CO2 emissions and anticipated an 8.8 percent reduction in CO2 in the first half of 2020 [1]. The COVID-19 epidemic caused the largest dramatic drop in worldwide CO2 emissions since World War II [2]. The Worldwide Atmospheric Research anticipated that global human fossil CO2 emissions in 2020 will be 5.1 percent lower than in 2019, at 36.0 Gt CO2, barely below the 36.2 Gt CO2 emission level recorded in 2013 [3]. Global carbon emissions (fossil fuels) per unit of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) decreased in 2019, averaging 0.298 t CO2/k USD/year, but per capita carbon emissions were steady at 4.93 t CO2/capita/year, confirming a 15.9 percent increase since 1990 [4].

To minimize the magnitude of global warming, substantial reductions in CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use are necessary. In view of the steadily increasing interest in preserving the environment and mitigating the consequences of climate change and global warming, hence, great attention is dedicated to finding alternative sustainable methods or eco-friendly economic materials to reduce the use of cement in various fields and consequently reduce the CO2 emissions accompanying with intensive energy consumed in the cement industry. Various additives have been mixed with cement such as bitumen [5[5][6],6], asphaltene [7], glass [8[8][9],9], polymers [10[10][11][12],11,12], nanomaterials [13[13][14],14], cement wastes [15[15][16],16], bio-waste [17,18,19][17][18][19] or natural clay [20,21][20][21] to improve the material features and minimize the cement incorporation and environmental pollution.

However, carbon-based liquid fuels will continue to be key energy storage media for the foreseeable future [22]. WResearchers suggest using solar energy to recycle atmospheric CO2 into liquid gasoline using a mix of mostly available technologies. The world population hit 7 billion in 2011 and is expected to exceed 9 billion by 2050, according to the United Nations, significantly increasing energy consumption. According to Hubbert’s peak theory, oil resources will plummet dramatically during the next 40 years [23]. As a result, the years 2055–2060 may be the last in which oil output reaches zero. Furthermore, while taking current energy usage into account, the World Coal Institute estimates that current coal reserves will last another 130 years, oil reserves for 42 years, and natural gas reserves for 60 years. The need to replace old fossil fuels with sustainable alternatives and new energy scenarios is thus becoming critical. Another major environmental worry is the rising quantities of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, which is caused by the combustion of fossil fuels and contributes to global warming [24].

Carbon capture allows for the production of low-carbon power from fossil fuels as well as the reduction of CO2 emissions from industrial operations, such as gas processing, cement production, and steel production, where alternative decarbonization options are restricted. CO2 capture and usage is gaining popularity across the world [24].

Human-caused CO2 increases have disastrous repercussions, such as rising average temperatures, melting sea ice, flooding, and sea level rise, harming global life, health, and the economy. The staggering difference between the total amount of carbon emitted worldwide as CO2 and the quantity of carbon present in five crucial carbon-containing commercial chemicals, not including derivative products such as ethylene oxide [25], underscores the grave consequences of continued carbon emissions. Even with indirect effects, the greatest quantity of CO2 that may be used remains quite little in comparison to total emissions. For example, if the whole worldwide yearly manufacturing of ethylene, the most extensively made commercial chemical containing carbon atoms, were carried out solely using carbon derived from CO2, this would result in direct usage of less than 1.5 percent of total global CO2 emissions [26]. Even with additional commercial chemicals included and indirect mitigation assumptions applied, possible usage might constitute just a tiny fraction of overall emissions. Naturally, this ignores the reality that direct CO2 conversion into hydrocarbons, particularly aromatics, is unlikely to become a commercial method in the near future.

Nonetheless, CO2 activation is exceedingly difficult since CO2 is a completely oxidized, thermodynamically stable, and chemically inactive molecule. Furthermore, hydrocarbon synthesis by CO2 hydrogenation frequently results in the creation of undesirable short-chain hydrocarbons rather than the desired long-chain hydrocarbons [27]. As a result, most research in this field has been on the sequential hydrogenation of CO2 to CH4, oxygenates, CH3OH, HCOOH, and light olefins (C2–C4 olefins). There have been few experiments on creating liquid hydrocarbons with molecular weights of C5+.

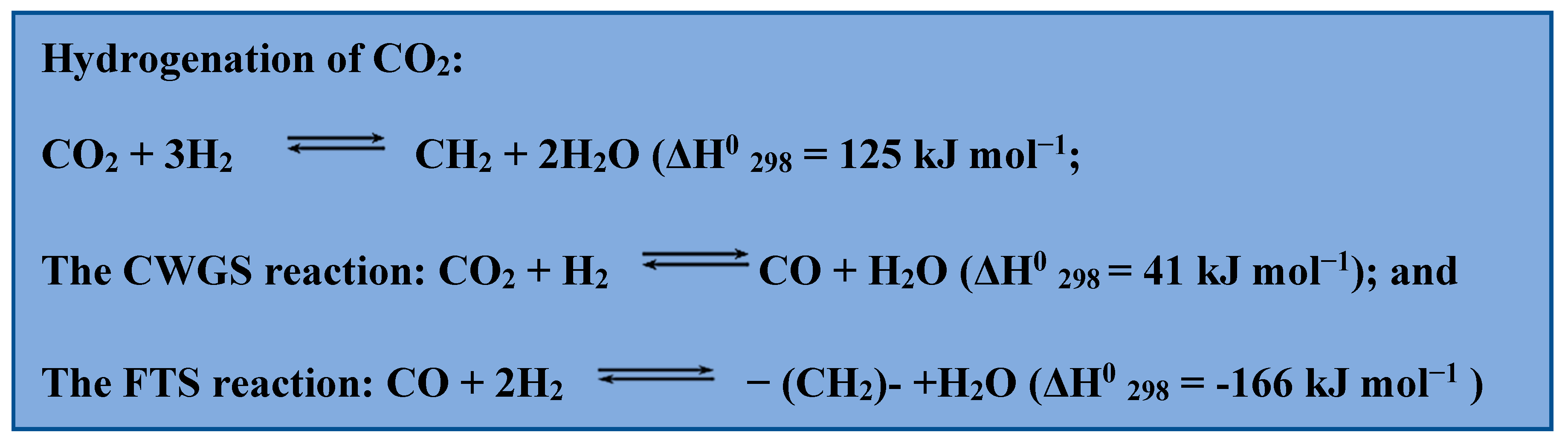

There are two methods of converting CO2 to hydrocarbon gas liquids: an indirect pathway that transforms CO2 to carbon monoxide (CO) or methanol and then to liquid hydrocarbons, or a direct CO2 hydrogenation route that combines CO2 reduction to CO through the use of the converse water-gas shift reaction shift (CWGS) and subsequent CO hydrogenation to long-chain hydrocarbons through the use of the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis (FTS) [28,29][28][29]. Secondly, the more direct technique is typically viewed as cheaper and ecologically acceptable since it requires fewer chemical process stages and uses less energy overall. The following chemical reactions are relevant for the production of hydrocarbon fuel (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Chemical reactions used to produce hydrocarbon fuels.

Mitigation of greenhouse gases is one of the most pressing issues confronting society today. As a result, the best strategy to minimize greenhouse gas emissions is to employ carbon-free sources that do not emit more CO2 into the environment [30]. However, there is significant promise in CO2 energy carriers and other materials, with several hurdles to overcome. Reduced CO2 emissions and conversion to renewable fuels and valuable chemicals have been proposed as possible ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions [30].

2. Global Warming and Sustainability

Producing energy from CO2 rather than absorbing and disposing of it is a sustainable energy technique. In reality, several thermochemical processes may transform CO2 into value-added compounds such as hydrogen, methanol, and ethanol [31]. These fuels may be utilized to power automobiles without requiring major modifications to existing internal combustion engines, paving the way for a more sustainable future. Discovering eco-friendly alternatives and new energy scenarios, primarily the conversion of CO2 into value-added chemicals using sunlight, is one of the top-most research priorities to overcome today’s extreme reducing the use of fossil fuels and mitigate the global warming risks associated with high CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere [32]. Because of decreased prices, quick commercial adoption, and complete industrial development, the use of second-generation green fuels is one of the most promising approaches to achieving industrial and ecological aims in the short term. A green fuel, unlike fossil fuel, does not emit more CO2 into the atmosphere since its burning, in the well-to-wheel cycle, creates a CO2 release equivalent to that required for its manufacture, closing the CO2 balance, and making it a carbon-neutral fuel [33]. The practical application of hydrogenation catalysts in conjunction with commercially viable research and innovation technology. Indeed, catalytic conversion of atmospheric CO2 into biofuels and fine chemicals would be one of the most economical and realistic solutions to the problem of greenhouse gas emissions, assuming that capture/sequestration and high-pressure storage technologies become commercially viable [34,35][34][35]. Nonetheless, in a very short time, the most prosecutable actions and encouraging prospects look upon the use of CO2-rich streams originating from industrial exhaust emissions, such as brick and cement work, despite the need for clean-up stages, as well as additional purification and concentration [36]. Haldor-Topsoe is at the vanguard of using CO2 as a carbon feedstock through various power-to-gas technologies, whereas ENI is redesigning its production lines with a greener vision, by developing new hydrogenation processes, called ENI EcofiningTM, for green-fuels synthesis, advantageously depicting the production of ultra-pure CO2 as industrial practice [37]. Despite significant advances in fuel science, the commercial and economic viability of hydrogen-to-liquid-fuels such as methanol is still being debated. The discovery of more effective catalyst substances for the efficient hydrogenation of CO2 looks to be of major importance in this scenario. CuO/ZnO-based catalysts, as is well known, offer lower costs and improved chemical stability when compared to other catalysts such as transition metal carbides (TMCs), bimetallic catalysts, or Au-supported catalysts [38]. Although CuO/ZnO/Al2O3 is the most extensively investigated catalyst for methanol synthesis, it was shown that the inclusion of ZrO2, CeO2, and TiO2 oxides improved both the activity and selectivity of CuO/ZnO-based catalysts in CO2 hydrogenation processes [39]. Recently the influence of replacing Al2O3 with CeO2 in the typical Cu-ZnO/Al2O3 catalytic discussed composition for syngas conversion, suggesting that the use of cerium oxide led to a remarkable positive effect on the catalyst stability, as a result of the preservation of the ratio of CuO/Cu+ on the catalyst surface. As well as, on the particle growth, due to the strong electron interactions of the copper/ceria phase (Cu/Cu2O/CuO, Ce3+/Ce4+) during hydrogenation reactions [40]. Metal dispersion and CO2 adsorption capacity are two key parameters affecting the CO2 hydrogenation functionality of Cu-based systems. Similarly, in our previous works, we esearchers displayed that the use of several oxides (i.e., ZnO, ZrO2, CeO2, Al2O3, Gd2O3, Ce2O3, and Y2O3) and alkaline metals (i.e., Li, Cs, and K) could remarkably influence both catalyst structure and morphology, balancing the amount of the diverse copper species (i.e., Cu°/Cu+/Cu2+) and leading to a notable improvement of the catalytic performance. On this account, ZrO2 has been shown to positively the affect morphology and texture of Cu-ZnO based catalysts, also favoring CO2 adsorption / activation and methanol selectivity, while CeO2 could act as both an electronic promoter and improver of surface functionality of Cu phase [41]. As reported in ourthe preliminary works, the scientists have proved a greater specific activity of CuZnO-CeO2 catalyst with respect to that of similar catalytic systems containing ZrO2 or other promoter oxides, facing several electronic and structural effects. Despite of a generally higher specific activity, wresearchers have evidenced that the CuZnO-Ceria catalyst suffers from several practical limitations, such as: a lower surface area, especially compared to that of ZrO2 and Al2O3 promoted catalysts.3. Green Hydrogen and Biofuel

Hydrogen has several benefits as an energy carrier and will play a key role in future energy production and circular economy [42]. Because hydrogen can be created in a climate-neutral way and emits only water when used, it is regarded as a climate-friendly energy carrier [43]. Hydrogen derived from renewable sources is commonly referred to as “green hydrogen.” It contrasts with “grey hydrogen,” which is defined as hydrogen derived from fossil, nonrenewable sources [44]. Currently, grey hydrogen generated by steam reforming of fossil natural gas accounts for the majority of worldwide hydrogen production [44]. Grey hydrogen may be converted to “blue hydrogen” by using carbon capture and storage technology, but it remains a non-renewable source [45]. To distinguish between carbon-neutral green and blue hydrogen, wresearchers coined the term “carbon-negative hydrogen.” Hydrogen has a wide range of uses due to its high gravimetric energy density, as well as its ease of storage and transportation [46]. Fuel cells may produce both electric power and heat from hydrogen. In the steel industry, hydrogen may also be utilized as a reducing agent [46]. It is regarded as an unavoidable basic building element in difficult-to-electrify zones [46]. Green hydrogen may be created using renewable power or renewable biomass, either through thermochemical processes or using microorganisms and biotechnological technologies. Biohydrogen, or hydrogen generated from biomass, can lead to more effective use of biogenic source materials by using residual and waste materials. Biohydrogen production technologies are classified as thermochemical or biotechnological. Biohydrogen may be generated on an industrial scale utilizing thermochemical methods from biomass (wood, straw, grass clippings, etc.) as well as other bioenergy sources (biogas, bioethanol, etc.) [43]. Gasification and pyrolysis are two types of thermochemical reactions. The synthesis gas produced by gasification or pyrolysis contains varying proportions of H2, CO2, carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), and other components such as nitrogen, water vapor, light hydrocarbons, hydrochloric acid, alkali chlorides, Sulphur compounds, biochar, or tar [47]. The following chemical processes occur as a result of subsequent steam reforming and/or water gas shift reactions, culminating in the creation of CO2 and hydrogen [48]. Minimal carbon-hydrogen (MCH) should be used initially in areas that are difficult to electrify directly [49]. WResearchers believe that generated bio-hydrogen is employed in difficult-to-electrify industrial sectors such as cement, steel, refining, ammonia, and glass. Refineries and ammonia plants are now the largest customers of hydrogen generated by steam methane reforming, a process that releases at least 10 kg CO2 for every kilogram H2 produced. Because many industries utilize carbon-intensive hydrogen, switching to MCH would be a near-term opportunity to increase hydrogen demand while lowering greenhouse gas emissions. Companies that are difficult to electrify may reduce their emissions and capture carbon dioxide by switching to alternative fuels and implementing carbon capture and storage technologies. This can help to enable their operations to contribute to the elimination of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Country-specific forecasts of European nations’ ultimate energy consumption in 2050 are unavailable and difficult to determine. As a result, scientists evaluate country-specific final energy consumption in 2019 and anticipate that 5–30% of final energy consumption will be fulfilled with low-carbon hydrogen to minimize hard-to-electrify emissions. These scenarios enable uresearchers to set upper and lower bounds on the amount of hydrogen likely required by each European country to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 [50].References

- Li, X.; Li, Z.; Su, C.-W.; Umar, M.; Shao, X. Exploring the Asymmetric Impact of Economic Policy Uncertainty on China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Market Price: Do Different Types of Uncertainty Matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 178, 121601.

- Liu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Deng, Z.; Lei, R.; Davis, S.J.; Feng, S.; Zheng, B.; Cui, D.; Dou, X.; Zhu, B. Near-Real-Time Monitoring of Global CO2 Emissions Reveals the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5172.

- Zhang, F.; Chen, C.; Yan, S.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, B.; Cheng, Z. Bi Nanocone Induced Efficient Reduction of CO2 to Formate with High Current Density. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2020, 598, 117545.

- Prasad, R.; Gupta, S.K.; Shabnam, N.; Oliveira, C.Y.B.; Nema, A.K.; Ansari, F.A.; Bux, F. Role of Microalgae in Global CO2 Sequestration: Physiological Mechanism, Recent Development, Challenges, and Future Prospective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13061.

- Saleh, H.M.; Bondouk, I.I.; Salama, E.; Esawii, H.A. Consistency and Shielding Efficiency of Cement-Bitumen Composite for Use as Gamma-Radiation Shielding Material. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2021, 137, 103764.

- Reda, S.M.; Saleh, H.M. Calculation of the Gamma Radiation Shielding Efficiency of Cement-Bitumen Portable Container Using MCNPX Code. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2021, 142, 104012.

- Saleh, H.M.; Bondouk, I.I.; Salama, E.; Mahmoud, H.H.; Omar, K.; Esawii, H.A. Asphaltene or Polyvinylchloride Waste Blended with Cement to Produce a Sustainable Material Used in Nuclear Safety. Sustainabilitiy 2022, 14, 3525.

- Eid, M.S.; Bondouk, I.I.; Saleh, H.M.; Omar, K.M.; Sayyed, M.I.; El-Khatib, A.M.; Elsafi, M. Implementation of Waste Silicate Glass into Composition of Ordinary Cement for Radiation Shielding Applications. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 54, 1456–1463.

- Eid, M.S.; Bondouk, I.I.; Saleh, H.M.; Omar, K.M.; Diab, H.M. Investigating the Effect of Gamma and Neutron Irradiation on Portland Cement Provided with Waste Silicate Glass. Sustainability 2022, 15, 763.

- Eskander, S.B.; Saleh, H.M.; Tawfik, M.E.; Bayoumi, T.A. Towards Potential Applications of Cement-Polymer Composites Based on Recycled Polystyrene Foam Wastes on Construction Fields: Impact of Exposure to Water Ecologies. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00664.

- Saleh, H.; Salman, A.; Faheim, A.; El-Sayed, A. Polymer and Polymer Waste Composites in Nuclear and Industrial Applications. J. Nucl. Energy Sci. Power Gener. Technol. 2020, 9, 11000199.

- Saleh, H.M.; Eskander, S.B. Impact of Water Flooding on Hard Cement-Recycled Polystyrene Composite Immobilizing Radioactive Sulfate Waste Simulate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 222, 522–530.

- Saleh, H.M.; El-Saied, F.A.; Salaheldin, T.A.; Hezo, A.A. Influence of Severe Climatic Variability on the Structural, Mechanical and Chemical Stability of Cement Kiln Dust-Slag-Nanosilica Composite Used for Radwaste Solidification. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 218, 556–567.

- Saleh, H.M.; El-Sheikh, S.M.; Elshereafy, E.E.; Essa, A.K. Performance of Cement-Slag-Titanate Nanofibers Composite Immobilized Radioactive Waste Solution through Frost and Flooding Events. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 221–232.

- Saleh, H.M.; Salman, A.A.; Faheim, A.A.; El-Sayed, A.M. Influence of Aggressive Environmental Impacts on Clean, Lightweight Bricks Made from Cement Kiln Dust and Grated Polystyrene. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00759.

- El-Sayed, A.M.; Faheim, A.A.; Salman, A.A.; Saleh, H.M. Sustainable Lightweight Concrete Made of Cement Kiln Dust and Liquefied Polystyrene Foam Improved with Other Waste Additives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15313.

- Saleh, H.M.; Aglan, R.F.; Mahmoud, H.H. Qualification of Corroborated Real Phytoremediated Radioactive Wastes under Leaching and Other Weathering Parameters. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2020, 119, 103178.

- Saleh, H.M.; Moussa, H.R.; El-Saied, F.A.; Dawoud, M.; Bayoumi, T.A.; Abdel Wahed, R.S. Mechanical and Physicochemical Evaluation of Solidified Dried Submerged Plants Subjected to Extreme Climatic Conditions to Achieve an Optimum Waste Containment. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2020, 122, 103285.

- Saleh, H.M.; Eskander, S.B. Long-Term Effect on the Solidified Degraded Cellulose-Based Waste Slurry in Cement Matrix. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2009, 14, 291–297.

- Saleh, H.M. Some Applications of Clays in Radioactive Waste Management. In Clays and Clay Minerals: Geological Origin, Mechanical Properties and Industrial Applications; Wesley, L.R., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 403–415. ISBN 978-1-63117-779-8.

- Bayoumi, T.A.; Reda, S.M.; Saleh, H.M. Assessment Study for Multi-Barrier System Used in Radioactive Borate Waste Isolation Based on Monte Carlo Simulations. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2012, 70, 99–102.

- Gielen, D.; Boshell, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilian, M.D.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The Role of Renewable Energy in the Global Energy Transformation. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2019, 24, 38–50.

- Priest, T. Hubbert’s Peak: The Great Debate over the End of Oil. Hist. Stud. Nat. Sci. 2014, 44, 37–79.

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Sustainable Energy Transition for Renewable and Low Carbon Grid Electricity Generation and Supply. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 9, 743114.

- Olivier, J.G.J.; Peters, J.A.H.W. Trends in Global CO2 and Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions. PBL Netherlands Environ. Assess. Agency 2020, 2020, 70.

- Wang, F.; Harindintwali, J.D.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, F.; Li, S.; Yin, Z.; Huang, L.; Fu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Technologies and Perspectives for Achieving Carbon Neutrality. Innovation 2021, 2, 100180.

- Numpilai, T.; Cheng, C.K.; Limtrakul, J.; Witoon, T. Recent Advances in Light Olefins Production from Catalytic Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 151, 401–427.

- Dowson, G.R.M.; Styring, P. Demonstration of CO2 Conversion to Synthetic Transport Fuel at Flue Gas Concentrations. Front. Energy Res. 2017, 5, 26.

- Gao, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, Y. Novel Heterogeneous Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation to Liquid Fuels. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1657–1670.

- Le Quéré, C.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, M.W.; Smith, A.J.P.; Abernethy, S.; Andrew, R.M.; De-Gol, A.J.; Willis, D.R.; Shan, Y.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. Temporary Reduction in Daily Global CO2 Emissions during the COVID-19 Forced Confinement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 647–653.

- Madejski, P.; Chmiel, K.; Subramanian, N.; Kuś, T. Methods and Techniques for CO2 Capture: Review of Potential Solutions and Applications in Modern Energy Technologies. Energies 2022, 15, 887.

- Ennaceri, H.; Abel, B. Conversion of carbon dioxide into storable solar fuels using solar energy. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Seoul, South Korea, 26–29 January 2019; IOP Publishing: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; Volume 291, p. 012038.

- Kumaravel, V.; Bartlett, J.; Pillai, S.C. Photoelectrochemical Conversion of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) into Fuels and Value-Added Products. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 486–519.

- Jiang, Z.; Xiao, T.; Kuznetsov, V.L.; Edwards, P.P. Turning Carbon Dioxide into Fuel. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 368, 3343–3364.

- Yuan, Z.; Eden, M.R.; Gani, R. Toward the Development and Deployment of Large-Scale Carbon Dioxide Capture and Conversion Processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 3383–3419.

- Markewitz, P.; Zhao, L.; Ryssel, M.; Moumin, G.; Wang, Y.; Sattler, C.; Robinius, M.; Stolten, D. Carbon Capture for CO2 Emission Reduction in the Cement Industry in Germany. Energies 2019, 12, 2432.

- Spadaro, L.; Palella, A.; Arena, F. Totally-green Fuels via CO2 Hydrogenation. Bull. Chem. React. Eng. Catal. 2020, 15, 390–404.

- Zhong, Z.; Etim, U.; Song, Y. Improving the Cu/ZnO-Based Catalysts for Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation to Methanol, and the Use of Methanol as a Renewable Energy Storage Media. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 545431.

- Allam, D.; Bennici, S.; Limousy, L.; Hocine, S. Improved Cu- and Zn-Based Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2019, 22, 227–237.

- Si, C.; Ban, H.; Chen, K.; Wang, X.; Cao, R.; Yi, Q.; Qin, Z.; Shi, L.; Li, Z.; Cai, W.; et al. Insight into the Positive Effect of Cu0/Cu+ Ratio on the Stability of Cu-ZnO-CeO2 Catalyst for Syngas Hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2020, 594, 117466.

- Nguyen, T.H.; Kim, H.B.; Park, E.D. CO and CO2 Methanation over CeO2-Supported Cobalt Catalysts. Catalysts 2022, 12, 212.

- Saeedmanesh, A.; Mac Kinnon, M.A.; Brouwer, J. Hydrogen Is Essential for Sustainability. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018, 12, 166–181.

- Full, J.; Merseburg, S.; Miehe, R.; Sauer, A. A new perspective for climate change mitigation—Introducing carbon-negative hydrogen production from biomass with carbon capture and storage (Hybeccs). Sustainability 2021, 13, 4026.

- Ringsgwandl, L.M.; Schaffert, J.; Brücken, N.; Albus, R.; Görner, K. Current Legislative Framework for Green Hydrogen Production by Electrolysis Plants in Germany. Energies 2022, 15, 1786.

- Ewing, M.; Israel, B.; Jutt, T.; Talebian, H.; Stepanik, L. Hydrogen on the Path to Net-Zero Emissions Costs and Climate Benefits; Pembina Institute: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2020.

- Tashie-Lewis, B.C.; Nnabuife, S.G. Hydrogen Production, Distribution, Storage and Power Conversion in a Hydrogen Economy—A Technology Review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2021, 8, 100172.

- Solid, M. Gasification of Densified Biomass (DB) and Municipal Solid Wastes (MSW) Using HTA/SG Technology. Processes 2021, 9, 2178.

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Hu, C. CeZrOx Promoted Water-Gas Shift Reaction under Steam–Methane Reforming Conditions. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1110.

- Rosa, L.; Mazzotti, M. Potential for Hydrogen Production from Sustainable Biomass with Carbon Capture and Storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112123.

- Van Der Spek, M.; Banet, C.; Bauer, C.; Gabrielli, P.; Goldthorpe, W.; Mazzotti, M.; Munkejord, S.T.; Røkke, N.A.; Shah, N.; Sunny, N.; et al. Environmental Science Perspective on the Hydrogen Economy as a Pathway. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 1034–1077.

More