1. Conceptualization of the Framework

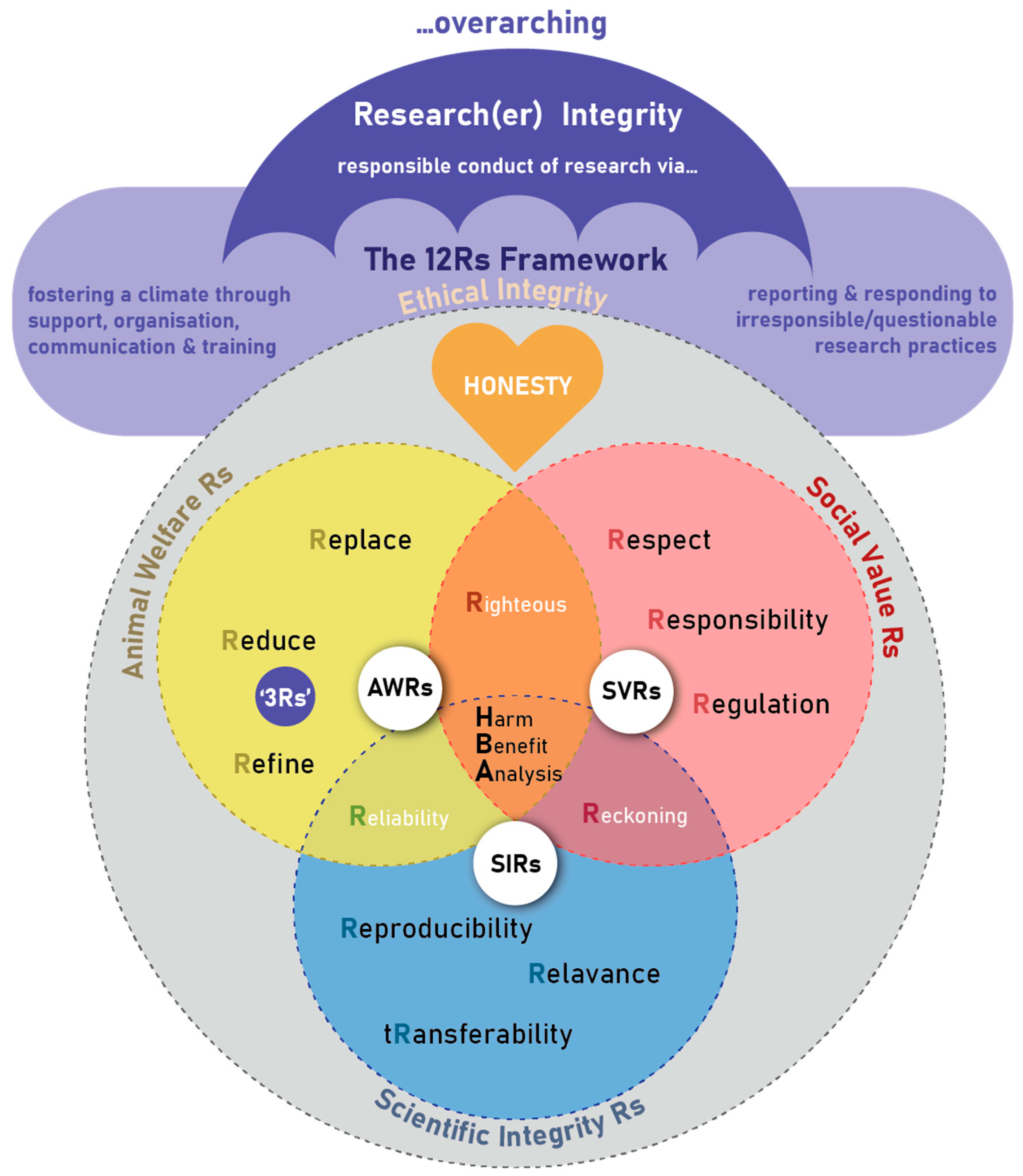

The framework is envisaged of consisting of different research ethics constructs linked together to form a unifying, comprehensive framework of 12 Rs (see Figure 1) that guides researchers using animals, the ethical oversight bodies, the animal facility (e.g., laboratory/research or other housing facility) or site (e.g., farm, wildlife) management and staff, to be ethical in their care of these animals as well as during the conduct of research. It becomes the compass for guiding and safeguarding all-inclusive “Ethical Conduct of Research” in the use of animals for scientific purposes (referred to as “ethical integrity” in the Figure 1). It provides a birds-eye-view of key principles during the planning, review, approval, conduct and monitoring processes of research with animals, as well as the undertaking and reporting of the care and use of these animals. Others that might find the framework useful are those who need to provide the appropriate infrastructure and professional guidance for animal studies, as well as animal owners, research institutions, and other stakeholders, to ensure comprehensive ethical oversight, management, and response.

Figure 1. The 12 Rs framework for the ethical use of animals in research ethics: a birds-eye view.

The research ethics principles are closely interlinked to an overarching umbrella of research integrity focusing on (1) the fostering of a climate of responsible conduct of research through providing support, organizational structures, effective communication and training opportunities, as well as (2) reporting and responding to irresponsible or questionable research practices through well-defined and described procedures and processes

[1].

“Honesty” or truthfulness is the cornerstone of the 12 Rs framework. However, it is not merely assumed to result from good intent, but needs to be actively pursued, and even tested to protect against unintentional or hidden deceit and misguidance. It often requires checks and balances, including independent assessment and review.

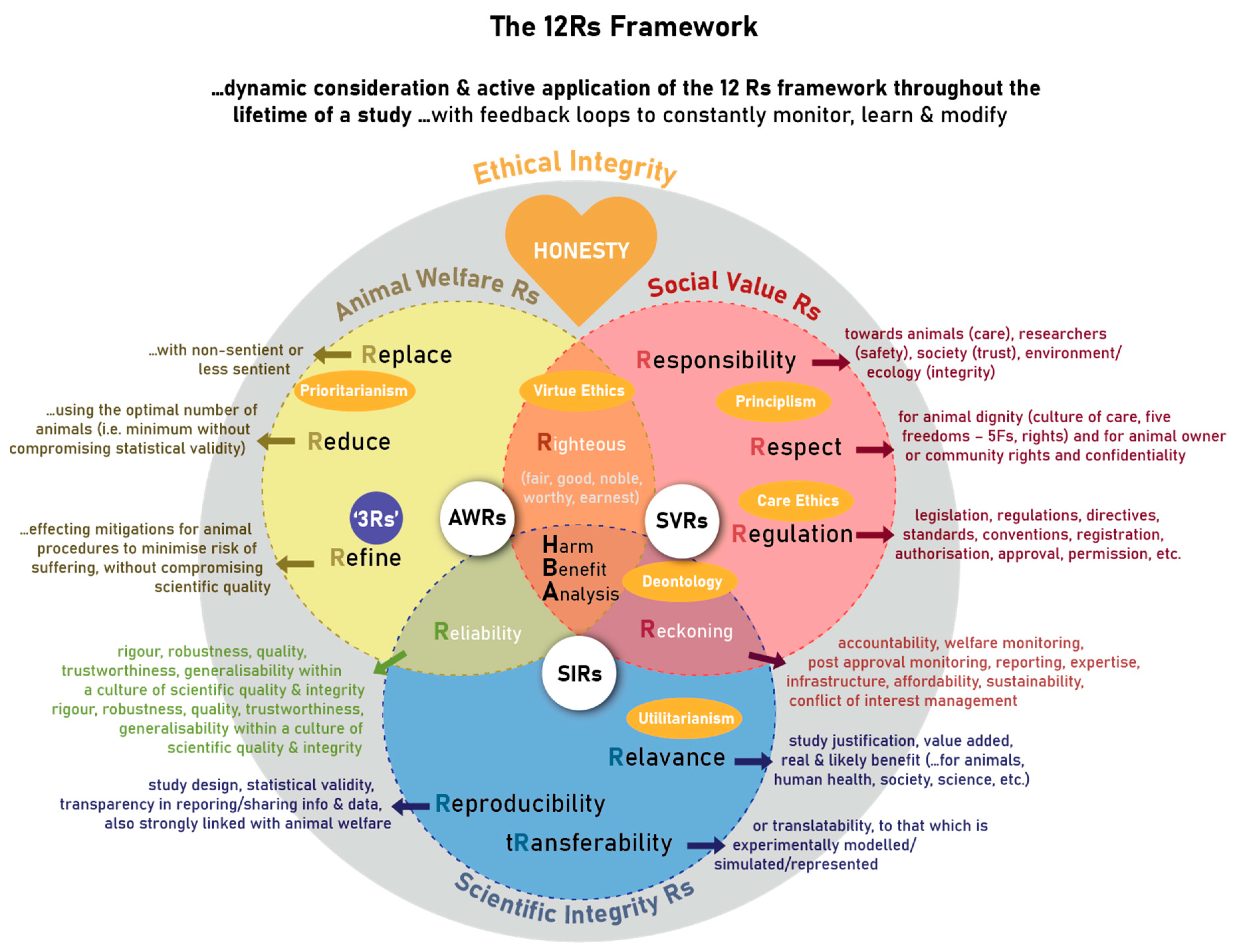

The 12 Rs are embedded in three main R domains: the Animal Welfare Rs (AWRs), the Social Value Rs (SVRs), and the Scientific Integrity Rs (SIRs), as well as Domain Intersecting Rs (DIRs) (Figure 2). The 12 Rs each encompass an important research ethics principle.

Figure 2. The more detailed exposition of the 12 Rs framework for the ethical use of animals in research ethics.

2. The Animal Welfare Rs (AWRs)

The Animal Welfare Rs cover the three Rs principles of

replace, reduce, and

refine [2], as alluded to

Figure 2. These principles were introduced to drive forward the implementation of the value of respect for animals and the importance of safeguarding animal welfare as central to animal research ethics. This value is increasingly being accepted and endorsed amongst the global research animal care and use community, as well as stakeholders and regulatory bodies around the world

[3]. The progressive creation of 3 Rs centres and platforms around the world

[4] has played a crucial role in promoting the adoption of these and other research ethics principles important to animal research ethics. To encourage uptake and implementation, these centres have made the information more accessible, providing educational resources, guidance, and other materials online as open access resources.

“Replace”, as first principle, implies an attempt to replace animals as sentient beings in experiments. This may play out as either absolute replacement by using humans, human tissue, or non-sentient alternatives to animals, or as relative replacement by using animal tissue after humane killing, or lastly by using less sentient animal alternatives, where such replacement will still allow achievement of the research objectives.

“Reduce”, as second principle if replacement in not possible, implies the implementation of the optimal number of animals to be used, being as few as possible without compromising scientific validity of the study.

“Refine”, as third principle, implies the optimisation of the experimental design and animal care and use (procedures) to minimise pain, suffering and distress. This could, for example, include environmental enrichment to optimise living conditions and quality of life, or anaesthesia to reduce pain. In other words, it is about effecting mitigations for animal care and use throughout its lifetime (cumulative effects of all factors on suffering, including the study-induced impact such as animal housing and experimental procedures), to minimise risk of suffering, without unduly compromising scientific quality.

Within this context, implementation of the animal welfare Rs (AWRs) should supersede scientific interest, but should not invalidate scientific interest.

3. The Social Value Rs (SVRs)

The Social Value Rs refers to Respect, Responsibility, and Regulations discussed and illustrated in in Figure 2.

“

Respect” refers to our regard for the animal’s dignity and wellbeing, as well as for animal owner’s or community’s rights and confidentiality. In terms of animal dignity, important concepts that have emerged include a culture of care

[5][6], the five freedoms-5Fs

[7], the five domains

[8] (conceptualised in 1994), and animal rights. These also impact on the application of, e.g., the AWRs, so that these principles cannot be viewed in isolation.

“Responsibility” refers to the obligation and accountability (see “Reckoning” below) of the investigator and research team towards the animals (regarding appropriate selection of animals and proper care–see the “Note!” below), researchers and technicians (regarding their biological safety), society (regarding the use of public funding and trust that science will be for the common good and that no unnecessary harms are being inflicted on animals), and the environment and ecology (regarding protection of its integrity and sustainability, as well as the protection of those who live/work in, or derive income from the land/environment).

“Regulation”, in the broader context, would refer to compliance with applicable national legislation and regulations (which are often vastly different across the globe, influenced by culture and beliefs), as well as with directives or standards, statutory and/or professional registration, authorisation, approval, accreditation, licence, permission (e.g., permits). It also refers to compliance with local policies and rules, local or universally adopted conventions, and even consideration of institutional rules, culture, and reputation.

Note! It is noted that in some contexts or countries choice is based on cost and availability, or even the lack of other non-animal resources. In such instances, it is crucial that proper consideration be given whether valid scientific information will be gained, whether proper measures can be implemented to protect animals against undue harm, and that benefit will indeed outweigh harm. In fact, invalid data resulting from inappropriate choices will contribute nothing to science, whilst harming animals and wasting resources. It may then be better to collaborate with scientists or groups that do have access to what is needed to achieve the study outcomes, or not use the animals at all.

4. The Scientific Integrity Rs (SIRs)

The Scientific Integrity Rs consists of Reproducibility, Relevance, and Transferability, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Scientific integrity refers to ensuring a sound research design and methodology that will result in reliable and valid data and outcomes that address the research objectives. The quality of the scientific data generated, and hence the trustworthiness of conclusions drawn, has been a highly contentious issue

[9][10]. A survey undertaken by Monya Baker, published for Nature reported that 70% of respondents could not replicate other researchers’ pre-clinical studies, with 50% also unable to repeat their own studies

[11]. This lack of reproducibility is unethical, animals have suffered unnecessarily, and human and financial resources have been wasted. As alluded to above, one example of how the community is addressing this is represented by the development of the PREPARE Guidelines for designing and planning studies

[12] and the ARRIVE Guidelines for reporting results

[13].

“

Reproducibility” is about data obtained from a robust study design to address the research questions, appropriate animal numbers, and statistical analyses to warrant statistical validity and transparency in the reporting and sharing of information to allow the data to be reproduced and its generalisability to be established. Providing comprehensive descriptions of methodology (as per the ARRIVE Guidelines) and the deposition of raw data in open access repositories, or publishing additional data as supplementary data together with articles, may enhance transparency and ultimately reproducibility. Critically, this is explicitly linked to animal welfare, with many studies demonstrating that in-appropriate animal welfare can modify or even change data

[14].

“Relevance” or significance of a study relates to its justification or value added, taking into account the real or expected/likely benefit to humans, animals or the environment. This is usually derived from the study and problem statement. Furthermore, it could relate to benefit for animal or human health, society, science, etc.

“

Transferability”: or translatability, relates to that which is experimentally modelled, simulated or represented. For animal models of human disease, translatability may refer to the validity of the animal model in terms of its face, predictive and construct validity

[15], and other criteria for validity

[16][17][18]. However, for different fields of science, e.g., wildlife or environmental studies, transferability may refer to the extent that the experimental sampling and design would represent the larger population under investigation (i.e., generalisability) or other species or environments.

5. The Domain Intersecting Rs (DIRs)

The three main Rs structures illuded to in Figure 2 have intersecting domains leading to three further principles namely Righteousness, Reliability, and Reckoning.

“Righteousness” represents the intersection of animal welfare (SIRs) and social values (SVRs) in striving to be fair, good, noble, worthy, and earnest scientists and members of society, and hence respectable science. It takes into account our values for life and fairness towards animals, and marries that with globally diverse cultural, religious, and/or social values related to our own responsibility, respect and legislative requirements.

“Reliability” represents the intersection of scientific integrity (SIRs) and animal welfare (AWRs). It relates to the robustness, quality, trustworthiness, applicability across environments or contexts, and generalisability of the data generated and conclusions drawn, embodied in a culture of scientific quality and integrity. How it links SIRs and AWRs can be seen in, as mentioned above, that animals that are well and free from suffering and distress, yield more trustworthy data, as opposed to unwell or otherwise suffering animals. On the other hand, scientific integrity ensures that the data generated from the use of animals are indeed yielding some real benefit in exchange for any loss of animal health and wellbeing.

“Reckoning” represents the intersection of scientific integrity (SIRs) and social values (SVRs). It refers to accountability, by measures during the planning and execution and after conclusion of an animal study. It is therefore foremostly pro-active by putting measures in place during the planning of a study, including for animal welfare, human safety and environmental integrity, aspects of respect towards animals and humans, ensuring that the study is sufficiently resourced, as well as legal compliance. In the spirit of harmonisation, rather than standardisation, all should be implemented taking into account also the local context of legislation, culture and values. Then, it is about actively caring about animals and other stakeholders during the execution of the study, in particular by vigilant implementation of animal welfare monitoring and other safety measures, identifying any planned and unforeseen consequences of/during the study, appropriate care and/or rehabilitation of animals after the study, as well as post approval monitoring and reporting any adverse event and immediately adjusting as necessary. In this regard, within a culture of care (as mentioned under the principle of “Respect”) and to be practical, the demonstration of respect towards co-workers (i.e., caring) would include not to ask of others to do what you are not willing to do. Lastly there is accountability measures in final study reporting to the ethical oversight body, robust and complete reporting to the scientific community and/or community and any post-study analyses. Throughout, there are other checks and balances, e.g., offered by experts, professionals, appropriate infrastructure and its standard operating procedures, assurance of affordability to complete a study, sustainability, and the management of any real or perceived conflict of interest.

6. Harm-Benefit Analysis as Culminating Point of the 12 Rs

The “

Harm-Benefit Analysis” forms the culmination and key ethical safeguard of the 12 Rs framework. This ethical safeguard, at the centre of the 12 Rs, indicates that above all the researchers will manage the harm done to the animals during research and ensure that the research does have benefit. It acknowledges that actual harm is done to animals by taking them out of their natural environment (contingent harms) and by subjecting them to experimental procedures (project related harms). It was first conceptualised in 1986 by Bateson

[19] and later refined by Pound and Nicol

[20] who described it as a “cornerstone of animal research regulation” and “key ethical safeguard”. Here, the benefit refers to value added to science, including to the betterment of human health or animal wellbeing, agriculture, conservation economy, or other scientific purposes, as alluded to above.

Analysis of

harm involves that researchers take into account the nature of the harm (physical, psychological, etc.), the degree and likelihood of the harm, the cumulative nature of harms, the justification of the harm (why it is necessary), and the mitigation to minimise the harm induced

[21][22]. Analysis of the

benefit is deduced from the

litrese

rature review arch and study objectives, the degree and likelihood of study success and benefit, as well as the nature and extent of the benefit (i.e., for animals, human health, society, environment, science, etc.)

[21][22].

Finally, it is determined via independent and informed discussion and deliberation (by all stakeholders and ultimately by the ethical oversight body or Regulatory Authority) whether benefit outweighs harm. In fact, as an example, the European Directive Article 36 clause 2 (EU Directive 2010/63) requires a favourable project evaluation, referring to Article 38, in which clause 2(d) specifically mentions the requirement for a harm-benefit analysis (EU Directive 2010/63).

Ultimately, the harm-benefit analysis takes into account all of the 12 Rs and becomes the final frontier that will determine whether a study will withstand the test of overall ethical integrity.