Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Roula KHALIL.

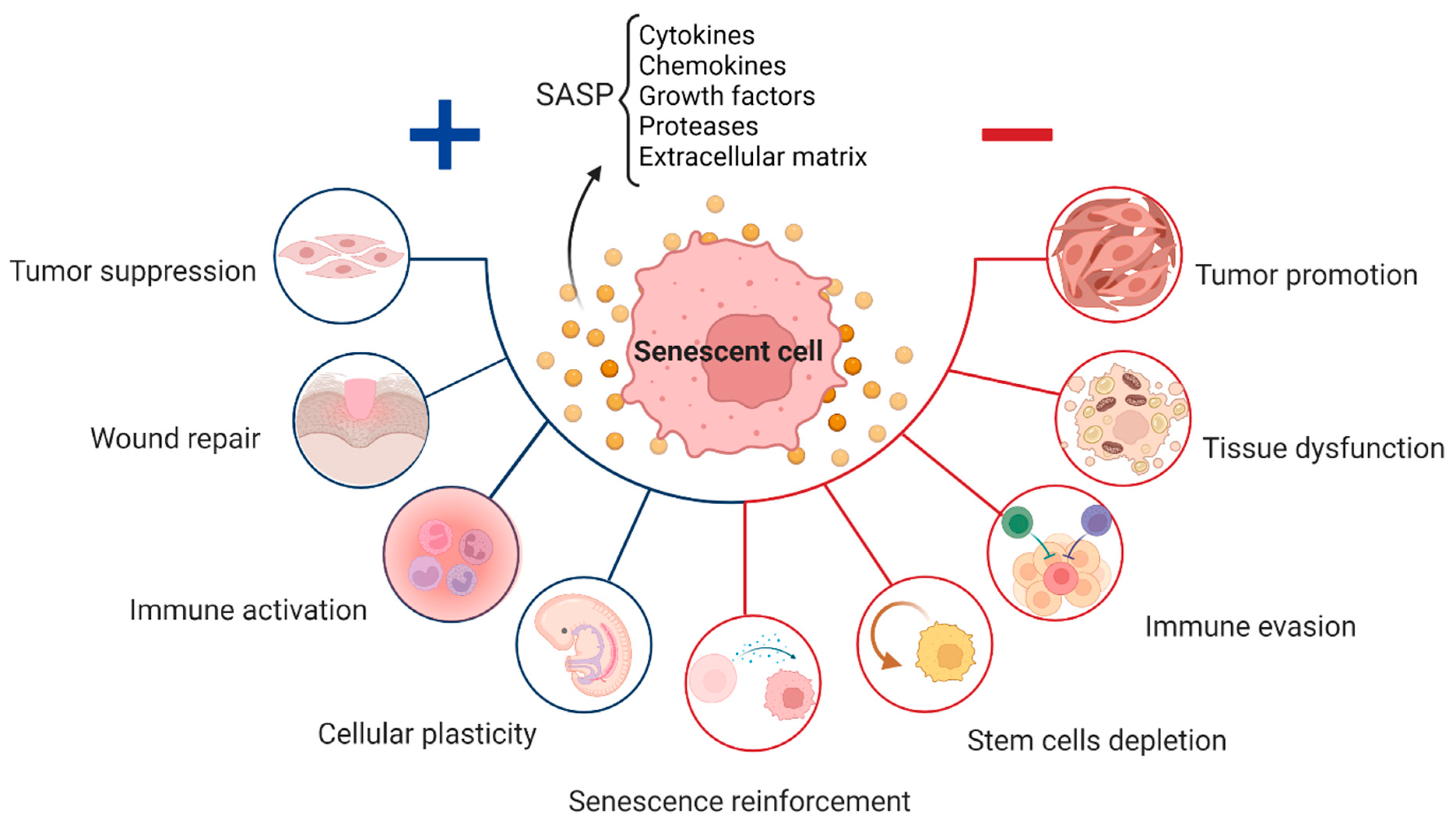

Cellular senescence is a physiological mechanism that has both beneficial and detrimental consequences. Senescence limits tumorigenesis, lifelong tissue damage, and is involved in different biological processes, such as morphogenesis, regeneration, and wound healing.

- cellular senescence

- age-related disorders

- SASP

- senolytic drugs

1. Introduction

It is definitely clear that living longer is a leading risk factor for increasing vulnerability to the development of the most prevalent pathologies, including cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer [1]. Increasing longevity presents a huge challenge for medical care, as aging progression is diverse and is not absolutely correlated to chronological age. Although a preventive medicine would have been the most suitable to prevent age related disease, pertinent biomarkers were not available to precisely measure precisely physiological age. However, new insights into the cellular and molecular events playing a role in biological aging led to the definition of a restricted set of biomarkers as potential targets to fight tissue aging deteriorations [2,3][2][3]. One emerging factor is the accumulation of senescent cells in tissues and organs, now considered as a common denominator in a vast majority of age-related pathologies [4,5][4][5]. Senescent cells are especially abundant at sites of age-related pathologies, and a great deal of evidence from mouse models demonstrated a causal role of senescent cells in several age-related diseases, such as sarcopenia, lordokyphosis, cataracts, osteoporosis, aged hematopoietic system, vasomotor dysfunction, atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration, idiopathic lung fibrosis, osteoarthritis, hepatic steatosis, and hair loss [6,7,8,9,10,11[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14],12,13,14], demonstrated by genetic approaches the clearance of p16-expressing senescent cells in mice models [15,16][15][16]. As this approach gave rise to a global delay of the onset of deterioration of several organs and the appearance of the corresponding age-related diseases, it led to a new paradigm considering aging as a disease and not only as a biological process. Targeting senescence seems to be a promising approach for treatment and prevention of aging to further promote an increased health longevity [17,18][17][18].

The fundamental characteristic of senescent cells is an irreversible cell cycle arrest that occurs in normal proliferating cells in response to various forms of cellular stress. Telomere shortening, UV radiation, increased levels of ROS species, oncogene activation, direct DNA damage, and other forms of stress that elicit activation of the DNA damage response pathway can lead to senescence [19,20,21,22][19][20][21][22]. Senescence was originally understood as a physiological cellular response aiming to prevent propagation of damaged cells in the organism [4,23,24,25,26,27,28,29][4][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]. Later, a number of additional beneficial functions, such as tissue repair, wound healing, and embryonic development, were discovered [5].

In addition to the protective role of cellular senescence, the long-term presence of senescent cells was revealed to be detrimental to the organism [5,30][5][30]. Indeed, the proliferative incompetency of senescent cells is accompanied by a resistance to apoptosis, as well as the secretion of a complex plethora of factors, referred to as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). It contains, chemokines, cytokines, tissue damaging proteases and growth factors, and proinflammatory factors that normally assist in their removal by the immune system [31,32][31][32]. Studies on diverse animal models indicate that multiple components of the immune system, including NK cells, T cells, and macrophages, are involved in controlling the presence of senescent cells in tissues [26,33,34,35,36,37][26][33][34][35][36][37]. The efficacy of this removal is variable among tissues and pathological conditions, and the mechanisms and rules regulating the homeostasis of senescent cells are yet to be fully understood. In the elderly, senescent cells and their SASP increasingly accumulate in tissues and contribute to the establishment of a chronic inflammation, so called “inflammaging”, due to continuous secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [24,38,39][24][38][39] considered as a feature of the majority of age-related diseases [40].

2. Senescence in Physiological Processes

Despite the detrimental effects of persistent cellular senescence and SASP being widely documented, these systems play crucial and appropriate roles in normal physiological processes, such as embryogenesis, wound healing, and fibrosis (Figure 1) [4,25,42,43][4][25][41][42]. Senescence is essential for the healthy functioning of several physiological processes, including embryonic development, wound healing, and fibrosis. This kind of senescence, also known as “acute senescence” [5], appears to be strictly controlled; it only affects a certain subset of tissue cells, which are then quickly eliminated by the immune system.

Figure 1. Role of senescent cells throughout life: positive (blue) and negative (red) effect depending on the level of senescence and SASP components released, including cytokines, chemokines, and other molecules, which affects the neighboring cells.

3. Senescence in Age-Related Diseases

Aging is the largest risk factor for developing many disorders, ranging from tissue degeneration to cancer. One pivotal driver of most of the major age-related pathologies is cellular senescence [2,5][2][5]. There are different types and mechanisms of senescent cells formation. Cellular senescence, as first described by Hayflick and Moorhead, referred to the finite lifespan of primary human fibroblasts in culture [48,49][47][48]. This observation describes only one particular type of cellular senescence that is caused by the attrition of telomeres, called replicative senescence (RS), a naturally occurring process that takes place every cell division [50][49]. Cellular senescence is induced by a variety of stress-causing, irreversible damages. These can include oncogene signaling, DNA damage, irradiation, or chemotherapy, causing the activation of tumor suppressor networks, including p53, p16, and p21, as well as cell cycle arrest [22,24,30,31,51][22][24][30][31][50]. In this case, it is categorized as a premature senescence. Thereby, senescence acts as intrinsic tumor suppressive mechanism that might prevent the proliferation of damaged cells. Irrespective of the stimulus, the senescence program is executed upon persistent activation of p53/p21 and/or RB/p16 tumor suppressor pathways, orchestrating the transition to and the maintenance of the senescent phenotype [24].References

- Acosta, J.C.; O’Loghlen, A.; Banito, A.; Guijarro, M.V.; Augert, A.; Raguz, S.; Fumagalli, M.; Da Costa, M.; Brown, C.; Popov, N.; et al. Chemokine Signaling via the CXCR2 Receptor Reinforces Senescence. Cell 2008, 133, 1006–1018.

- Agostini, A.; Mondragón, L.; Bernardos, A.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Marcos, M.D.; Sancenón, F.; Soto, J.; Costero, A.; Manguan-García, C.; Perona, R.; et al. Targeted Cargo Delivery in Senescent Cells Using Capped Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10556–10560.

- Ahadi, S.; Zhou, W.; Rose, S.M.S.-F.; Sailani, M.R.; Contrepois, K.; Avina, M.; Ashland, M.; Brunet, A.; Snyder, M. Personal aging markers and ageotypes revealed by deep longitudinal profiling. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 83–90.

- Akbar, A.N.; Henson, S.M.; Lanna, A. Senescence of T Lymphocytes: Implications for Enhancing Human Immunity. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 866–876.

- Alcorta, D.A.; Xiong, Y.; Phelps, D.; Hannon, G.; Beach, D.; Barrett, J.C. Involvement of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 (INK4a) in replicative senescence of normal human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 13742–13747.

- Alimbetov, D.; Davis, T.; Brook, A.J.C.; Cox, L.S.; Faragher, R.G.A.; Nurgozhin, T.; Zhumadilov, Z.; Kipling, D. Suppression of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in human fibroblasts using small molecule inhibitors of p38 MAP kinase and MK2. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 305–315.

- Alimonti, A.; Nardella, C.; Chen, Z.; Clohessy, J.G.; Carracedo, A.; Trotman, L.C.; Cheng, K.; Varmeh, S.; Kozma, S.C.; Thomas, G.; et al. A novel type of cellular senescence that can be enhanced in mouse models and human tumor xenografts to suppress prostate tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 681–693.

- Aliouat-Denis, C.-M.; Dendouga, N.; Van den Wyngaert, I.; Goehlmann, H.; Steller, U.; van de Weyer, I.; Van Slycken, N.; Andries, L.; Kass, S.; Luyten, W.; et al. p53-Independent Regulation of p21<sup>Waf1/Cip1</sup> Expression and Senescence by Chk2. Mol. Cancer Res. 2005, 3, 627.

- Alle, Q.; Le Borgne, E.; Bensadoun, P.; Lemey, C.; Béchir, N.; Gabanou, M.; Estermann, F.; Bertrand-Gaday, C.; Pessemesse, L.; Toupet, K.; et al. A single short reprogramming early in life initiates and propagates an epigenetically related mechanism improving fitness and promoting an increased healthy lifespan. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13714.

- Althubiti, M.; Lezina, L.; Carrera, S.; Jukes-Jones, R.; Giblett, S.M.; Antonov, A.; Barlev, N.; Saldanha, G.S.; A Pritchard, C.; Cain, K.; et al. Characterization of novel markers of senescence and their prognostic potential in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1528.

- Amor, C.; Feucht, J.; Leibold, J.; Ho, Y.-J.; Zhu, C.; Alonso-Curbelo, D.; Mansilla-Soto, J.; Boyer, J.A.; Li, X.; Giavridis, T.; et al. Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence-associated pathologies. Nature 2020, 583, 127–132.

- Anestakis, D.; Petanidis, S.; Kalyvas, S.; Nday, C.M.; Tsave, O.; Kioseoglou, E.; Salifoglou, A. Mechanisms and applications of interleukins in cancer immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 1691–1710.

- Arunachalam, G.; Samuel, S.M.; Marei, I.; Ding, H.; Triggle, C.R. Metformin modulates hyperglycaemia-induced endothelial senescence and apoptosis through SIRT1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 523–535.

- Astle, M.V.; Hannan, K.M.; Ng, P.Y.; Lee, R.S.; George, A.J.; Hsu, A.K.; Haupt, Y.; Hannan, R.D.; Pearson, R.B. AKT induces senescence in human cells via mTORC1 and p53 in the absence of DNA damage: Implications for targeting mTOR during malignancy. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1949–1962.

- Baar, M.P.; Brandt, R.M.C.; Putavet, D.A.; Klein, J.D.D.; Derks, K.W.J.; Bourgeois, B.R.M.; Stryeck, S.; Rijksen, Y.; Van Willigenburg, H.; Feijtel, D.A.; et al. Targeted Apoptosis of Senescent Cells Restores Tissue Homeostasis in Response to Chemotoxicity and Aging. Cell 2017, 169, 132–147.e116.

- Baird, D.M.; Rowson, J.; Wynford-Thomas, D.; Kipling, D. Extensive allelic variation and ultrashort telomeres in senescent human cells. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 203–207.

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; Saltness, R.A.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; et al. Naturally occurring p16Ink4a-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–189.

- Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Tchkonia, T.; Lebrasseur, N.K.; Childs, B.G.; Van De Sluis, B.; Kirkland, J.L.; Van Deursen, J.M. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 2011, 479, 232–236.

- Baruch, K.; Deczkowska, A.; Rosenzweig, N.; Tsitsou-Kampeli, A.; Sharif, A.M.; Matcovitch-Natan, O.; Kertser, A.; David, E.; Amit, I.; Schwartz, M. PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade reduces pathology and improves memory in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 135–137.

- Barzilai, N.; Crandall, J.P.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Espeland, M.A. Metformin as a Tool to Target Aging. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1060–1065.

- Basisty, N.; Kale, A.; Jeon, O.H.; Kuehnemann, C.; Payne, T.; Rao, C.; Holtz, A.; Shah, S.; Sharma, V.; Ferrucci, L.; et al. A proteomic atlas of senescence-associated secretomes for aging biomarker development. PLOS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000599.

- Bernadotte, A.; Mikhelson, V.M.; Spivak, I.M. Markers of cellular senescence. Telomere shortening as a marker of cellular senescence. Aging 2016, 8, 3–11.

- Bernardes de Jesus, B.; Vera, E.; Schneeberger, K.; Tejera, A.M.; Ayuso, E.; Bosch, F.; Blasco, M.A. Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012, 4, 691–704.

- Bhaumik, D.; Scott, G.K.; Schokrpur, S.; Patil, C.K.; Orjalo, A.V.; Rodier, F.; Lithgow, G.J.; Campisi, J. MicroRNAs miR-146a/b negatively modulate the senescence-associated inflammatory mediators IL-6 and IL-8. Aging 2009, 1, 402–411.

- Borghesan, M.; Fafián-Labora, J.; Eleftheriadou, O.; Carpintero-Fernández, P.; Paez-Ribes, M.; Vizcay-Barrena, G.; Swisa, A.; Kolodkin-Gal, D.; Ximénez-Embún, P.; Lowe, R.; et al. Small Extracellular Vesicles Are Key Regulators of Non-cell Autonomous Intercellular Communication in Senescence via the Interferon Protein IFITM3. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 3956–3971.

- Boucher, M.-J.; Jean, D.; Vézina, A.; Rivard, N. Dual role of MEK/ERK signaling in senescence and transformation of intestinal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2004, 286, G736–G746.

- Boumendil, C.; Hari, P.; Olsen, K.C.; Acosta, J.C.; Bickmore, W.A. Nuclear pore density controls heterochromatin reorganization during senescence. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 144–149.

- Braig, M.; Lee, S.; Loddenkemper, C.; Rudolph, C.; Peters, A.H.; Schlegelberger, B.; Stein, H.; Dörken, B.; Jenuwein, T.; Schmitt, C.A. Oncogene-induced senescence as an initial barrier in lymphoma development. Nature 2005, 436, 660–665.

- Burton, D.; Krizhanovsky, V. Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 4373–4386.

- Burton, D.G.; Stolzing, A. Cellular senescence: Immunosurveillance and future immunotherapy. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 43, 17–25.

- Bussian, T.J.; Aziz, A.; Meyer, C.F.; Swenson, B.L.; Van Deursen, J.M.; Baker, D.J. Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature 2018, 562, 578–582.

- Cádiz-Gurrea, M.D.L.L.; Borrás-Linares, I.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Joven, J.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Segura-Carretero, A. Cocoa and Grape Seed Byproducts as a Source of Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Proanthocyanidins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 376.

- Calcinotto, A.; Kohli, J.; Zagato, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Demaria, M.; Alimonti, A. Cellular Senescence: Aging, Cancer, and Injury. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1047–1078.

- Campbell, J.M.; Bellman, S.M.; Stephenson, M.D.; Lisy, K. Metformin reduces all-cause mortality and diseases of ageing independent of its effect on diabetes control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 31–44.

- Campisi, J. Senescent Cells, Tumor Suppression, and Organismal Aging: Good Citizens, Bad Neighbors. Cell 2005, 120, 513–522.

- Campisi, J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 685–705.

- Cang, S.; Iragavarapu, C.; Savooji, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, D. ABT-199 (venetoclax) and BCL-2 inhibitors in clinical development. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 8, 129.

- Capell, B.C.; Drake, A.M.; Zhu, J.; Shah, P.P.; Dou, Z.; Dorsey, J.; Simola, D.F.; Donahue, G.; Sammons, M.; Rai, T.S.; et al. MLL1 is essential for the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 321–336.

- Chang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, L.; Laberge, R.-M.; DeMaria, M.; Campisi, J.; Janakiraman, K.; Sharpless, N.E.; Ding, S.; Feng, W.; et al. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 78–83.

- Chen, Z.; Trotman, L.C.; Shaffer, D.; Lin, H.-K.; Dotan, Z.A.; Niki, M.; Koutcher, J.A.; Scher, H.I.; Ludwig, T.; Gerald, W.; et al. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature 2005, 436, 725–730.

- Childs, B.G.; Baker, D.J.; Kirkland, J.L.; Campisi, J.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescence and apoptosis: Dueling or complementary cell fates? EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 1139–1153.

- Childs, B.G.; Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Conover, C.A.; Campisi, J.; Van Deursen, J.M. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science 2016, 354, 472–477.

- Childs, B.G.; Gluscevic, M.; Baker, D.J.; Laberge, R.-M.; Marquess, D.; Dananberg, J.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescent cells: An emerging target for diseases of ageing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 718–735.

- Citrin, D.E.; Shankavaram, U.; Horton, J.A.; Shield, W., 3rd.; Zhao, S.; Asano, H.; White, A.; Sowers, A.; Thetford, A.; Chung, E.J. Role of type II pneumocyte senescence in radiation-induced lung fibrosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1474–1484.

- Collado, M.; Gil, J.; Efeyan, A.; Guerra, C.; Schuhmacher, A.J.; Barradas, M.; Benguria, A.; Zaballos, A.; Flores, J.M.; Barbacid, M.; et al. Tumour biology: Senescence in premalignant tumours. Nature 2005, 436, 642.

- Collado, M.; Serrano, M. Senescence in tumours: Evidence from mice and humans. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 51–57.

- Coppé, J.-P.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Krtolica, A.; Campisi, J. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype: The Dark Side of Tumor Suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2010, 5, 99–118.

- Coppé, J.-P.; Patil, C.K.; Rodier, F.; Krtolica, A.; Beauséjour, C.M.; Parrinello, S.; Hodgson, J.G.; Chin, K.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J. A Human-Like Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype Is Conserved in Mouse Cells Dependent on Physiological Oxygen. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9188.

- Coppé, J.-P.; Patil, C.K.; Rodier, F.; Sun, Y.; Muñoz, D.P.; Goldstein, J.; Nelson, P.S.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J. Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotypes Reveal Cell-Nonautonomous Functions of Oncogenic RAS and the p53 Tumor Suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e301.

- Coppé, J.-P.; Rodier, F.; Patil, C.K.; Freund, A.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J. Tumor Suppressor and Aging Biomarker p16INK4a Induces Cellular Senescence without the Associated Inflammatory Secretory Phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 36396–36403.

More