You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Jessie Wu and Version 2 by Jessie Wu.

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are often considered a “safe substitute” for conventional cigarette cessation. The composition of the fluid is not always clearly defined and shows a large variation within brands and manufacturers. More than 80 compounds were detected in liquids and aerosols. E-cigarettes contain nicotine, and the addition of flavorings increases the toxicity of e-cigarette vapour in a significant manner. The heat generated by the e-cigarette leads to the oxidation and decomposition of its components, eventually forming harmful constituents in the inhaled vapour. The effects of these toxicants on male and female reproduction are well established in conventional cigarette smokers.

- e-cigarette

- oocyte

- sperm

1. E-Cigarettes: Types, Usage

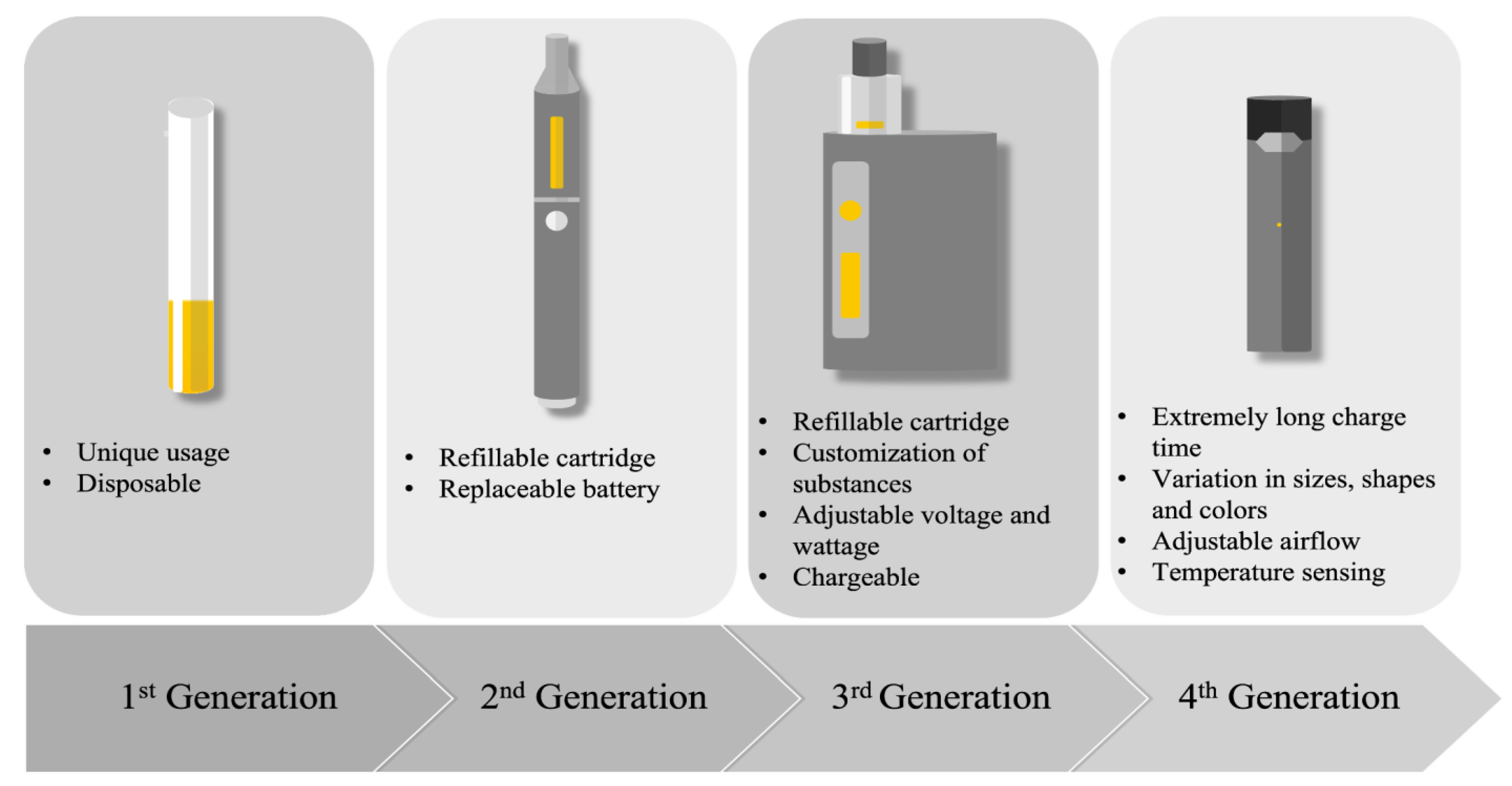

Since they were placed on the market, e-cigarettes have undergone major evolutions (Figure 1). These devices have been called several different names and were manufactured in a large range of shapes, sizes, and types. Four generations of e-cigarettes have been developed so far (Figure 1). Overall, its main components remain unchanged and consist of a cartridge that contains a fluid, an atomizer that acts as a heating element to vapourize the e-liquid into an aerosol, a sensor that is required to turn on the device, and a battery that provides the current needed to heat the atomizer [1]. The first generation of e-cigarettes were primarily designed for “one-time use” since they were not rechargeable or refillable. The evolution of the second generation brought devices with refillable e-liquid cartridges and batteries that could be replaced. The third generation was designed to be used multiple times and permitted the customization of the substances found in the e-liquid. Pod-Mods, the fourth generation of e-cigarettes, included all the features of the previous generation, and came in a wide variety of shapes, sizes, and colors.

Figure 1. Description of the four generations of e-cigarettes.

2. Reprotoxicological Profile of E-Cigarette Components

Due to the numerous components and varying concentrations of substances found in e-liquid, the precise toxic effect of e-cigarette utilisation on reproduction is hard to determine. Each component on its own could have deleterious effects on one’s reproduction. Moreover, substance interaction adds complexity to conclusively determining the negative effects of vaping on one’s reproductive health. Generally, our knowledge of the toxic effects of e-cigarette components are known through studies of conventional cigarettes. However, as discussed above, e-cigarettes vary largely from conventional cigarettes. Comprehensive analyses have shown that many of these substances have a negative impact on reproduction, among them.

2.1. Nicotine

The reprotoxicity of nicotine is largely documented in relation to conventional cigarette smoking. Although knowledge about the exposure to nicotine in the context of e-cigarette utilisation is limited, it has gained interest over the past few years. Nicotine disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in acute and chronic smokers [2][3]. The reproductive system is under the control of several sexual hormones like follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, sex hormone-binding globulin, and cortisol, whose levels were found to be altered in nicotine consumers [4][5]. Nicotine is also known to be a powerful vasoconstrictor that can impair sexual and erectile functions [6].

Nicotine was also shown to have an effect on reproduction at the gonadal level. Indeed, nicotine triggers oxidative stress in the testis, resulting in a global alteration of testis function, with a decrease in testosterone level, lower epididymal sperm number and viability, and increased levels of apoptosis in spermatogonia and spermatocytes [7][8][9][10]. Semen and serum nicotine levels showed a negative correlation with sperm concentration [11]. A significant decrease in sperm motility was also described in infertile and fertile men displaying high serum nicotine levels with a dose-specific effect on sperm motility and morphology [12][13]. Moreover, sperm function was not left unaffected by exposure to nicotine since lower sperm fertilizing capacity and viability were described in men with higher nicotine levels [13]. Lastly, the ultrastructure and motility machinery functions in spermatozoa were reported to be modified at a higher incidence in nicotine consumers [14].

The process of fertilization is also a target of nicotine since one of its crucial events, acrosomal reaction, was shown to be significantly altered by nicotine [15]. Nicotine reduces offspring numbers and induces abnormal and delayed implantation in e-cigarette exposed female mice. The impaired implantation seen in relation to nicotine consumption was linked to a decrease in endometrial thickness caused by impaired blood flow to the uterine tissue [16][17]. Similarly, there was a marked decrease in blood flow in both the maternal uterine and fetal umbilical circulation when females were exposed to nicotine during pregnancy. These females gave birth to pups showing significantly reduced body weight and length with behavioural changes [18][19]. Interestingly, in bovine studies, nicotine was shown to impair cellular division and chromosomal alignment, leading to a decrease in the quality and quantity of cultured blastocysts [20].

2.2. Flavouring Compounds

The effect of flavours added to e-cigarette fluid was assessed on reproductive ability and outcomes mainly in animal models. It was demonstrated that long-term daily exposure to nicotine-free flavoured e-cigarette vapour induced low testis weight, increased apoptosis in testes, increased oxidative stress, and an increase in the inhibition of the expression of main steroidogenesis enzymes [9][21].

Moreover, elevated sperm DNA fragmentation levels in mouse testes were also described after long-term exposure to e-cigarette flavours [21]. Bubble gum flavour was found to damage germ cells, while cinnamon altered germ-cell precursors in exposed mouse testes [21]. Moreover, increased teratozoospermia, mainly in the form of abnormal flagellum, was observed in rats exposed to e-cigarette flavours [8]. Experiments in zebra fish showed that cinnamaldehyde, a constituent of the bubble gum flavour adversely affected embryo development [22]. Similar fetal weight and crown-rump length were observed in rat newborns whose mothers were exposed to juice flavor [18].

A human study exposing spermatozoa to nicotine-free cinnamon and bubble gum flavoured e-cigarettes showed a decrease in sperm motility [21]. The reprotoxicity studies on e-cigarette flavouring compounds are scarce, and further investigations are needed, particularly in humans.

2.3. Heavy Metals

As a consequence of the heating process of e-fluid and the device components, e-cigarettes release numerous metal nanoparticles such as lead, nickel, chromium, aluminum, iron, copper, silver, zinc, tin, manganese, ceramic, and silica [19][23]. Although the impact of male exposure to these metals in the context of e-cigarette utilisation has not yet been proven, environmental exposure to these nanoparticles was shown to negatively affect human sperm concentration, sperm motility, and sperm function with a potential effect on fertility status [24][25][26][27][28][29]. At high concentrations, cadmium was reported to have detrimental effects on human, bovine, and murine oocyte maturation, fertilization, early cleavage, and blastocyst development rates [20][30]. Copper was also found to negatively impact embryo development in a dose-dependent manner [31]. The female reproductive system seems to also be a target of heavy metals. While the mechanism remains to be clarified, ovarian steroidogenesis, including estradiol, FSHR, StAR, CYP11A1, CYP19A1, HSD3β1 and SF-1 levels, were found to be disrupted in women and rats exposed to copper and nickel [32][33]. These observations were accompanied by increased apoptotic cell numbers and inflammation levels in the ovaries [32]. Lastly, parental occupational exposure to lead was suspected to increase the risk of spontaneous abortion and congenital malformations [34].

2.4. E-Cigarette Vapour

E-cigarette utilisation generates vapour that is a mixture of diverse components, including TSNA, acrolein, glycidol, formaldehyde, VOCs, and PAH [23]. The reprotoxicity of formaldehyde was largely studied in animal models. It showed the ability to alter testis structure, induce sperm parameter defects, and modify sexual behaviour [35][36]. Long-term exposure to formaldehyde increases oxidative stress, resulting in adverse effects on rat ovarian histology with a dramatic decrease in mature follicle number and size [37]. Although there have been few studies conducted in humans, formaldehyde is acknowledged as reprotoxic. A negative impact on semen motility was observed in men exposed to formaldehyde vapour at work [38]. Similarly, environmental exposure to VOCs and PAH adversely affects endocrine function and semen quality (sperm counts and morphology), ultimately causing reproductive issues [39][40][41]. VOCs are well known to have detrimental effects on embryo development resulting in decreased IVF success chances since they have lower implantation and pregnancy rates [42][43].

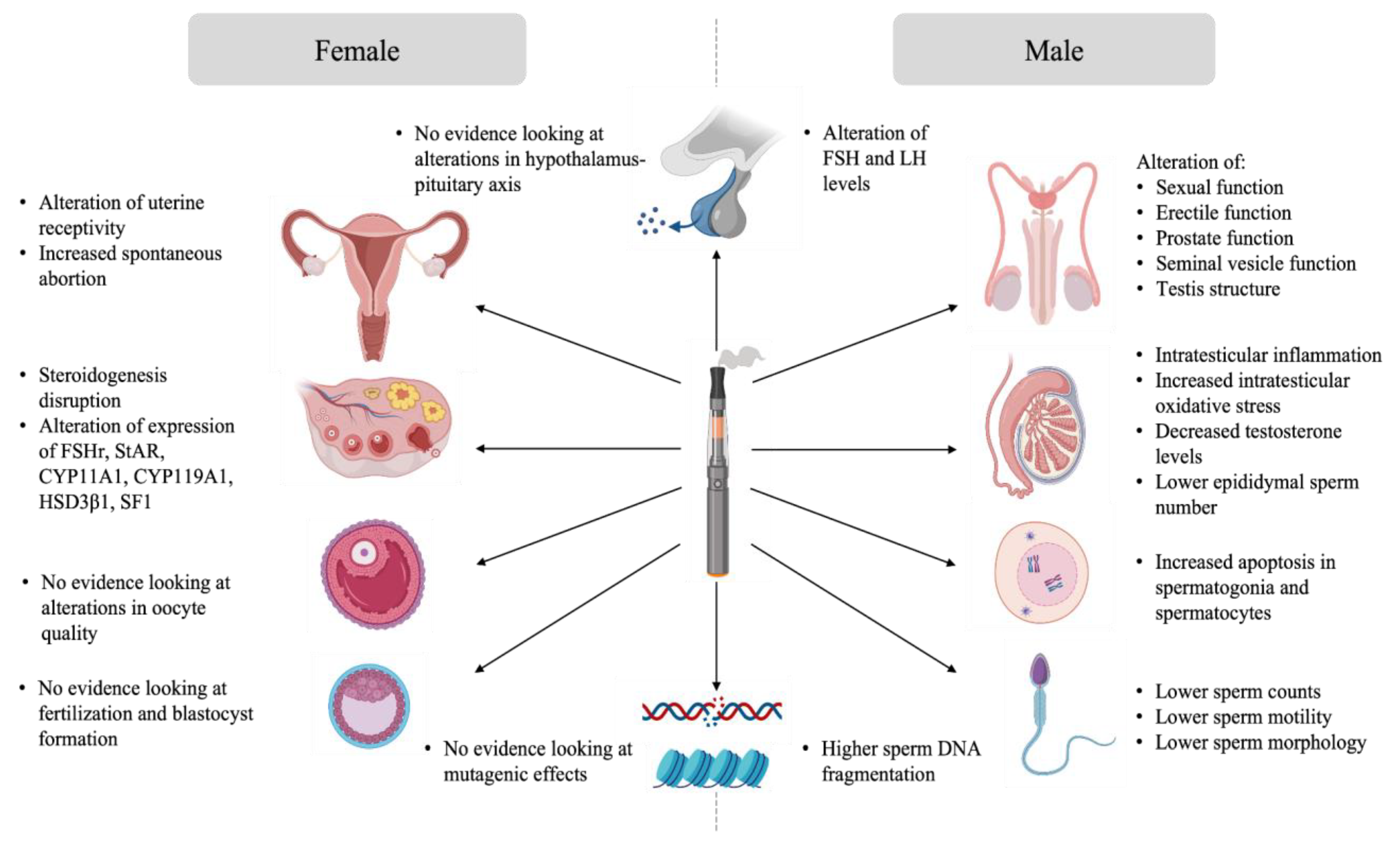

3. Evidence of the Impact of E-Cigarette Exposure on Reproduction

As previously mentioned, data about the potential impact of e-cigarette exposure on reproduction is limited. Studies tackling this topic were conducted mainly in animal models under experimental conditions that do not reproduce the utilisation of e-cigarettes in humans. However, the outcome of these studies remains informative. This section aims to provide an overview of the evidence of the impact of e-cigarette exposure on male and female gonads, gametes, the reproductive tract, and subsequently on reproduction. A summary of the proposed effects of e-cigarette-mediated reproductive disruption is available in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Effects of e-cigarette-mediated reproductive disruption.

3.1. Evidence Analysis of the Impact of E-Cigarette on Male Reproduction

While studies on the effect of e-cigarettes on human male reproduction are limited, numerous groups have investigated their effect in animal models.

Exposure to e-cigarettes was reported to disturb the hypothalamo-pituitary axis, resulting in altered gonadal function and semen quality (Figure 32). Indeed, Wawryk-Gawda and collaborators showed that in male rats exposed to e-cigarette vapour had increased apoptosis in spermatogonia and spermatocyte, an alteration of the morphology and function of the seminiferous epithelium, as well as unica albuginea malformations [10]. Other studies linked e-cigarette utilisation with steroidogenesis disruption and global disorganisation of the testes, accompanied by significant desquamation of germ cells [7][8][9]. Moreover, low testicular weight and a higher apoptotic cell number in the testis was observed in the context of e-cigarette exposure [9][21]. Intraperitoneal injection of e-cigarette liquid in male rats induced toxicity and testicular inflammation, which, in turn, affected sperm production and sperm quality with lower sperm density, reduction of epididymal sperm number, and lower sperm viability [7][8][10]. When inhaled for 4 weeks by male rats, the same flavoring induced apoptosis in testes [21]. The sperm of rats exposed to e-cigarette vapour showed increased teratozoospermia (looped tail, flagellar angulation, and complete absence of flagellum) [8][9][10]. Studies showed that sperm chromatin integrity could also be affected by e-cigarette exposure. In fact, higher DNA damage was observed in both testis and sperm of exposed rats [9][21]. These findings suggest potential mutagenic effects of e-cigarettes on sperm.

Little to no studies have corroborated these findings in humans. A preliminary study, presented at the British Fertility Society Conference in 2017, investigating the effect of e-cigarette flavouring on human sperm, showed a significant decrease in motility in specimen cultured with e-liquid flavouring [21]. This research and the results obtained in animal models all suggest that vaping could have pathogenic effects on male reproduction and caution should be used when vaping and trying to conceive.

3.2. Evidence Analysis of the Impact of E-Cigarette on Female Reproduction

Evidence of the impact of e-cigarettes on female reproduction suggests that the female reproductive system is not left unaffected by exposure to e-cigarettes (Figure 3). Unlike sperm, there is no evidence linking the impact of e-cigarette utilisation on intrinsic oocyte quality and oocyte genome integrity. However, some data suggests that ovarian function is impaired in animal models exposed to e-cigarettes. Indeed, a decreased percentage of normal follicles was described in the ovaries of female rats exposed to e-cigarette fluid [44]. Hormone levels were also affected in these animals, where a reduction in estrogen secretion was observed [44]. Implantation and pregnancy outcomes were also affected in mice exposed to e-cigarette vapour. Microarray analysis showed an alteration in uterine receptivity transcripts in e-cigarette exposed mice. These females experienced a delay in embryo implantation, although the animals showed high progesterone levels, resulting in a decreased offspring number [45].

Interestingly, some studies suggest that e-cigarette exposure not only has a negative impact on one’s reproductive health but also on the offspring when exposed to e-cigarette components in utero. In fact, there was a trend towards lower fertility in male offspring and lower body weight and length in all offspring [45][46][47][48]. These findings suggest a hypothetical toxicity of e-cigarette exposure on an in utero developing fetus. Neonatal exposure to e-cigarette induced altered lung growth, weight gain with significant and persistent behavioral alterations [47]. This raises the question of the potential impact of e-cigarettes on non-users that are passively exposed to the vapour during pregnancy.

3.3. Evidence Analysis of the Impact of E-Cigarette on Assisted Reproductive Technologies Outcomes

Very little is known about the true impact of e-cigarette utilisation on assisted reproductive technologies (ART) outcomes. Luckily, many studies have investigated the deleterious effect of conventional smoking in relation to ART outcomes, providing some basis for what could be expected from e-cigarette utilisation. Smoking has many negative effects on ART outcomes. In males, smoking has been shown to decrease spermogram quality and increase the risk of pregnancy loss, both of which would have a significant impact on ART outcomes [49]. In females, smoking was associated with a lower number of oocytes obtained during an oocyte retrieval procedure and a poorer response to ovarian stimulation [49][50]. Finally, in couples doing IVF, higher rates of miscarriage and lower chances of achieving pregnancy were observed in women who smoked conventional cigarettes [3][51][52]. While most studies concluded that there was a time-dependent and dose-dependent effect of smoking, all results suggested a negative impact of smoking on ART treatment outcomes.

While there are no prospective studies assessing the direct reproductive effects of e-cigarette use on ART outcomes, studies have suggested that the use of e-cigarettes can provide levels of nicotine and other metabolites that are similar to those produced by traditional cigarettes [53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60]. Therefore, it would be wise to assume that e-cigarettes would have similar negative effects on ART outcomes than those observed in traditional cigarette consumers, until further demonstrated otherwise. It would thus be beneficial to promote awareness of its potential negative impact on ART outcomes before commencing a treatment plan.

References

- Bertholon, J.F.; Becquemin, M.H.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Dautzenberg, B. Electronic cigarettes: A short review. Respiration 2013, 86, 433–438.

- Weisberg, E. Smoking and reproductive health. Clin. Reprod. Fertil. 1985, 3, 175–186.

- Jandíková, H.; Dušková, M.; Stárka, L. The influence of smoking and cessation on the human reproductive hormonal balance. Physiol. Res. 2017, 66, S323–S331.

- Ochedalski, T.; Lachowicz-Ochedalska, A.; Dec, W.; Czechowski, B. Examining the effects of tobacco smoking on levels of certain hormones in serum of young men. Ginekol. Pol. 1994, 65, 87–93.

- Vine, M.F. Smoking and male reproduction: A review. Int. J. Androl. 1996, 19, 323–337.

- Harte, C.B.; Meston, C.M. Acute Effects of Nicotine on Physiological and Subjective Sexual Arousal in Nonsmoking Men: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 110–121.

- El Golli, N.; Rahali, D.; Jrad-Lamine, A.; Dallagi, Y.; Jallouli, M.; Bdiri, Y.; Ba, N.; Lebret, M.; Rosa, J.; El May, M.; et al. Impact of electronic-cigarette refill liquid on rat testis. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2016, 26, 417–424.

- Rahali, D.; Jrad-Lamine, A.; Dallagi, Y.; Bdiri, Y.; Ba, N.; El May, M.; El Fazaa, S.; El Golli, N. Semen Parameter Alteration, Histological Changes and Role of Oxidative Stress in Adult Rat Epididymis on Exposure to Electronic Cigarette Refill Liquid. Chin. J. Physiol. 2018, 61, 75–84.

- Vivarelli, F.; Canistro, D.; Cirillo, S.; Cardenia, V.; Rodriguez-Estrada, M.T.; Paolini, M. Impairment of testicular function in electronic cigarette (e-cig, e-cigs) exposed rats under low-voltage and nicotine-freeconditions. Life Sci. 2019, 228, 53–65.

- Wawryk-Gawda, E.; Zarobkiewicz, M.K.; Chłapek, K.; Chylinska-Wrzos, P.; Jodłowska-Jedrych, B. Histological changes in the reproductive system of male rats exposed to cigarette smoke or electronic cigarette vapor. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2019, 101, 404–419.

- Pacifici, R.; Altieri, I.; Gandini, L.; Lenzi, A.; Pichini, S.; Rosa, M.; Zuccaro, P.; Dondero, F. Nicotine, cotinine, and trans-3-hydroxycotinine levels in seminal plasma of smokers: Effects on sperm parameters. Ther. Drug Monit. 1993, 15, 358–363.

- Sharma, R.; Harlev, A.; Agarwal, A.; Esteves, S.C. Cigarette Smoking and Semen Quality: A New Meta-analysis Examining the Effect of the 2010 World Health Organization Laboratory Methods for the Examination of Human Semen. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 635–645.

- Vine, M.F.; Tse, C.K.; Hu, P.; Truong, K.Y. Cigarette smoking and semen quality. Fertil. Steril. 1996, 65, 835–842.

- Harlev, A.; Agarwal, A.; Gunes, S.O.; Shetty, A.; du Plessis, S.S. Smoking and Male Infertility: An Evidence-Based Review. World J. Men Health 2015, 33, 143–160.

- El Mulla, K.F.; Köhn, F.M.; El Beheiry, A.H.; Schill, W.B. The effect of smoking and varicocele on human sperm acrosin activity and acrosome reaction. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 3190–3194.

- Soares, S.; Simón, C.; Remohi, J.; Pellicer, A. Cigarette smoking affects uterine receptiveness. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 22, 543–547.

- Heger, A.; Sator, M.; Walch, K.; Pietrowski, D. Smoking Decreases Endometrial Thickness in IVF/ICSI Patients. Geburtshilfe Und Frauenheilkd. 2018, 78, 78–82.

- Orzabal, M.R.; Lunde-Young, E.R.; Ramirez, J.I.; Howe, S.Y.; Naik, V.D.; Lee, J.; Heaps, C.L.; Threadgill, D.W.; Ramadoss, J. Chronic exposure to e-cig aerosols during early development causes vascular dysfunction and offspring growth deficits. Transl. Res. 2019, 207, 70–82.

- Szumilas, K.; Szumilas, P.; Grzywacz, A.; Wilk, A. The Effects of E-Cigarette Vapor Components on the Morphology and Function of the Male and Female Reproductive Systems: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6152.

- Akar, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Khalıd, M. The effect of cadmium on the bovine in vitro oocyte maturation and early embryo development. Int. J. Veter Sci. Med. 2018, 6, S73–S77.

- O’Neill, H.; Nutakor, A.; Magnus, E.; Bracey, E.; Williamson, E.; Harper, J. Effect of Electronic-Cigarette Flavourings on (I) Human Sperm Motility, Chromatin Integrity in Vitro and (II) Mice Testicular Function in Vivo. 2017. Available online: http://srf-reproduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Fertility-2017-Final-Programme-and-Abstracts.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Holden, L.L.; Truong, L.; Simonich, M.T.; Tanguay, R.L. Assessing the hazard of E-Cigarette flavor mixtures using zebrafish. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 136, 110945.

- Thirión-Romero, I.; Pérez-Padilla, R.; Zabert, G.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, I. Respiratory impacy of electronic cigarettes and “low-risk” tobacco. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2019, 71, 17–27.

- Marzec-Wróblewska, U.; Kamiński, P.; Lakota, P.; Szymański, M.; Wasilow, K.; Ludwikowski, G.; Kuligowska-Prusińska, M.; Odrowąż-Sypniewska, G.; Stuczyński, T.; Michałkiewicz, J. Zinc and iron concentration and SOD activity in human semen and seminal plasma. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 143, 167–177.

- Marzec-Wróblewska, U.; Kamiński, P.; Łakota, P.; Szymański, M.; Wasilow, K.; Ludwikowski, G.; Jerzak, L.; Stuczyński, T.; Woźniak, A.; Buciński, A. Human Sperm Characteristics with Regard to Cobalt, Chromium, and Lead in Semen and Activity of Catalase in Seminal Plasma. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 188, 251–260.

- Shi, X.; Chan, C.P.S.; Man, G.K.Y.; Chan, D.Y.L.; Wong, M.H.; Li, T.C. Associations between blood metal/ metalloid concentration and human semen quality and sperm function: A cross-sectional study in Hong Kong. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2021, 65, 126735.

- Zhang, X.F.; Gurunathan, S.; Kim, J.H. Effects of silver nanoparticles on neonatal testis development in mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 6243–6256.

- Zhang, T.; Ru, Y.F.; Bin Wu, B.; Dong, H.; Chen, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Effects of low lead exposure on sperm quality and sperm DNA methylation in adult men. Cell Biosci. 2021, 30, 110–150.

- Chen, C.; Li, B.; Huang, R.; Dong, S.; Zhou, Y.; Song, J.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, X. Involvement of Ca2+ and ROS signals in nickel-impaired human sperm function. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113181.

- Zhao, L.L.; Ru, Y.F.; Liu, M.; Tang, J.N.; Zheng, J.F.; Wu, B.; Gu, Y.H.; Shi, H.J. Reproductive effects of cadmium on sperm function and early embryonic development in vitro. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186727.

- Roychoudhury, S.; Nath, S.; Massanyi, P.; Stawarz, R.; Kacaniova, M.; Kolesarova, A. Copper-induced changes in reproductive functions: In vivo and in vitro effects. Physiol. Res. 2016, 65, 11–22.

- Kong, L.; Tang, M.; Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Hu, K.; Lu, W.; Wei, C.; Liang, G.; Pu, Y. Nickel Nanoparticles Exposure and Reproductive Toxicity in Healthy Adult Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 21253–21269.

- Yiqin, C.; Yan, S.; Peiwen, W.; Yiwei, G.; Qi, W.; Qian, X.; Panglin, W.; Sunjie, Y.; Wenxiang, W. Copper exposure disrupts ovarian steroidogenesis in human ovarian granulosa cells via the FSHR/CYP19A1 pathway and alters methylation patterns on the SF-1 gene promoter. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 356, 11–20.

- Anttila, A.; Sallmén, M. Effects of parental occupational exposure to lead and other metals on spontaneous abortion. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1995, 37, 915–921.

- Vosoughi, S.; Khavanin, A.; Salehnia, M.; Mahabadi, H.A.; Shahverdi, A.; Esmaeili, V. Adverse Effects of Formaldehyde Vapor on Mouse Sperm Parameters and Testicular Tissue. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 6, 250–267.

- Zang, Z.-J.; Fang, Y.-Q.; Ji, S.-Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.-Q.; Xia, T.-T.; Jiang, M.-H.; Zhang, Y.-N. Formaldehyde Inhibits Sexual Behavior and Expression of Steroidogenic Enzymes in the Testes of Mice. J. Sex. Med. 2017, 14, 1297–1306.

- Wang, H.-X.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zhou, D.-X.; Zheng, L.-R.; Zhang, J.; Huo, Y.-W.; Tian, H. Effects of low-dose, long-term formaldehyde exposure on the structure and functions of the ovary in rats. Toxicol. Ind. Heal. 2012, 29, 609–615.

- Wang, H.-X.; Li, H.-C.; Lv, M.-Q.; Zhou, D.-X.; Bai, L.-Z.; Du, L.-Z.; Xue, X.; Lin, P.; Qiu, S.-D. Associations between occupation exposure to Formaldehyde and semen quality, a primary study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15874.

- Balabanič, D.; Rupnik, M.S.; Klemenčič, A.K. Negative impact of endocrine-disrupting compounds on human reproductive health. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2011, 23, 403–416.

- Longo, V.; Forleo, A.; Ferramosca, A.; Notari, T.; Pappalardo, S.; Siciliano, P.; Capone, S.; Montano, L. Blood, urine and semen Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) pattern analysis for assessing health environmental impact in highly polluted areas in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 286, 117410.

- Yang, P.; Wang, Y.-X.; Chen, Y.-J.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Huang, Z.; Lu, W.-Q.; Zeng, Q. Urinary Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Metabolites and Human Semen Quality in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 958–967.

- Khoudja, R.Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, T.; Zhou, C.J. Better IVF outcomes following improvements in laboratory air quality. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2013, 30, 69–76.

- Hall, J.; Gilligan, A.; Schimmel, T.; Cecchi, M.; Cohen, J. The origin, effects and control of air pollution in laboratories used for human embryo culture. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 13 (Suppl. S4), 146–155.

- Chen, T.; Wu, M.; Dong, Y.; Kong, B.; Cai, Y.; Hei, C.; Wu, K.; Zhao, C.; Chang, Q. Effect of e-cigarette refill liquid on follicular development and estrogen secretion in rats. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2022, 20, 36.

- Wetendorf, M.; Randall, L.T.; Lemma, M.T.; Hurr, S.H.; Pawlak, J.B.; Tarran, R.; Doerschuk, C.M.; Caron, K.M. E-Cigarette Exposure Delays Implantation and Causes Reduced Weight Gain in Female Offspring Exposed In Utero. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 1907–1916.

- McGrath-Morrow, S.A.; Hayashi, M.; Aherrera, A.; Lopez, A.; Malinina, A.; Collaco, J.M.; Neptune, E.; Klein, J.D.; Winickoff, J.P.; Breysse, P.; et al. The Effects of Electronic Cigarette Emissions on Systemic Cotinine Levels, Weight and Postnatal Lung Growth in Neonatal Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118344.

- Smith, D.; Aherrera, A.; Lopez, A.; Neptune, E.; Winickoff, J.P.; Klein, J.D.; Chen, G.; Lazarus, P.; Collaco, J.M.; McGrath-Morrow, S.A. Adult Behavior in Male Mice Exposed to E-Cigarette Nicotine Vapors during Late Prenatal and Early Postnatal Life. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137953.

- Greene, R.M.; Pisano, M.M. Developmental toxicity of e-cigarette aerosols. Birth Defects Res. 2019, 111, 1294–1301.

- Firns, S.; Cruzat, V.; Keane, K.N.; Joesbury, K.A.; Lee, A.H.; Newsholme, P.; Yovich, J.L. The effect of cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and fruit and vegetable consumption on IVF outcomes: A review and presentation of original data. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 134.

- Freour, T.; Masson, D.; Mirallie, S.; Jean, M.; Bach, K.; Dejoie, T.; Barriere, P. Active smoking compromises IVF outcome and affects ovarian reserve. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2008, 16, 96–102.

- Klonoff-Cohen, H. Female and male lifestyle habits and IVF: What is known and unknown. Hum. Reprod. Update 2005, 11, 179–203.

- Klonoff-Cohen, H.; Natarajan, L.; Marrs, R.; Yee, B. Effects of female and male smoking on success rates of IVF and gamete intra-Fallopian transfer. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 16, 1382–1390.

- Pisinger, C.; Døssing, M. A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes. Prev. Med. 2014, 69, 248–260.

- Fuoco, F.; Buonanno, G.; Stabile, L.; Vigo, P. Influential parameters on particle concentration and size distribution in the mainstream of e-cigarettes. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 184, 523–529.

- Pellegrino, R.M.; Tinghino, B.; Mangiaracina, G.; Marani, A.; Vitali, M.; Protano, C.; Osborn, J.F.; Cattaruzza, M.S. Electronic cigarettes: An evaluation of exposure to chemicals and fine particulate matter (PM). Ann. Ig. 2012, 24, 279–288.

- Williams, M.; Villarreal, A.; Bozhilov, K.; Lin, S.; Talbot, P. Metal and silicate particles including nanoparticles are present in electronic cigarette cartomizer fluid and aerosol. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57987.

- Lerner, C.A.; Sundar, I.K.; Watson, R.M.; Elder, A.; Jones, R.; Done, D.; Kurtzman, R.; Ossip, D.J.; Robinson, R.; McIntosh, S.; et al. Environmental health hazards of e-cigarettes and their components: Oxidants and copper in e-cigarette aerosols. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 198, 100–107.

- McAuley, T.R.; Hopke, P.; Zhao, J.; Babaian, S. Comparison of the effects of e-cigarette vapor and cigarette smoke on indoor air quality. Inhal. Toxicol. 2012, 24, 850–857.

- Goniewicz, M.L.; Knysak, J.; Gawron, M.; Kosmider, L.; Sobczak, A.; Kurek, J.; Prokopowicz, A.; Jablonska-Czapla, M.; Rosik-Dulewska, C.; Havel, C.; et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob. Control 2014, 23, 133–139.

- St. Helen, G.; Havel, C.; Dempsey, D.A.; Jacob, P., 3rd; Benowitz, N.L. Nicotine delivery, retention and pharmacokinetics from various electronic cigarettes. Addiction 2016, 111, 535–544.

More