You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Thierry Yonga Chuengwa and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

There is growing interest for manufacturing enterprises to embrace the drivers of the Smart Industry paradigm. Among these drivers, human–robot physical co-manipulation of objects has gained significant interest in the literature on assembly operations. Motivated by the requirement for human dyads between the human and the robot counterpart, the study of task allocation in human-robot collaboration literature shows promising trends for the implementation of ergonomics in collaborative assembly.

- HRC

- co-assembly

- task allocation

- modeling

- posture estimation

- muscle fatigue

1. Task Allocation

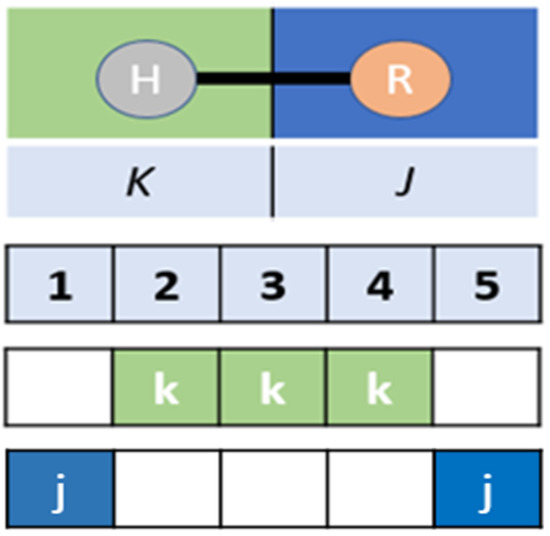

Task allocation in manufacturing is the problem of evaluating and assigning operations to existing resources within the most feasible sequence that improves economic performance and social benefits [1][41]. Traditionally, the division of tasks between the active resources of the production line was based on fixed rules, and both humans and robots performed high-frequency repetitive operations [2][26]. The allocation of tasks between the human and the robot primarily aims to follow the criteria that satisfy the respective capabilities of the individual resources. Attention must be given to the kind of resources used based on their competence and capabilities [3][39]. At a deterministic level, HRC deals with the paradigm of shared sequential task execution between the human and the robot. As shown in Figure 15, a task sequence comprising n = five operations is distributed between the human (H) and the robot (R). The human performs tasks k2, k3 and k4, while the robot performs tasks J1, and J5.

Figure 15. Task allocation between the human and robot.

Current shared industrial workplaces bring numerous uncertainties that cannot be anticipated with rigid automation. Co-operation-based assembly through task sharing using human intelligence for decision making and robots for accurate execution is critical for workload planning in the production environment [4][5][42,43]. Task allocation problems in assembly, commonly known as the assembly line balancing problem (ALBP), emerge when the assembly process must be redesigned based on optimization criteria for the proper re-assigning of tasks [3][6][39,44].

Several modeling tools are available for solving the task sequence problem. Difficulty score sheets in design for assembly (DFA) were used in [7][8][24,45] to provide a good understanding of the attributes that affect the human–robot task assignment. The concept of dynamic function allocation was studied in [9][46] to resolve the problem of an unbalanced workload by changing the levels of human/machine controls over system functions, which lead into more situational awareness of human factors in automation. The authors in [10][47] proposed the disassembly sequence planning model that is capable of minimizing the disassembly time without violating the human safety and the resources constraints.

In solving the task allocation problem in the design phase, the authors in [11][48] used the nominal schedule to best distribute the work among actors. Following an AND/OR graph, the scheduler is capable of allocating the most suitable task for each actor to execute at each point in time, whereby human expertise is exploited to improve the collaboration. While most studies consider the single human–robot collaborative system, Liau and Ryu [12][49] studied two different HRC modes, namely, multi-station and flexible modes. Through simulation, they proposed a three-level task allocation model to improve the cycle time, human capability and ergonomic factors.

Beyond the suitability of the task distribution strategy, the capability of the HRC system and the optimization of the assembly cycle time and line balancing can also be studied if an appropriate task allocation model demonstrates sufficient levels of situational awareness. This assigns adjustable roles to the active resources in a manner that determines the limits of acceptable physical work requirements. Furthermore, the design of task allocation that ignores the human factors can lead to economic costs associated with health damage and the loss of productivity due to absenteeism [13][16].

2. Ergonomics in Collaborative Assembly

The requirement of integrating the human factors in operations involving manual material handling has become a growing trend in research. In the effort to involve human analysis in collaborative work design, ergonomics focuses on the human physical and cognitive characteristics and describe the science of designing appropriate working conditions [6][44]. There are two key aspects considered below: occupational health and safety.

3. Intelligent Controllers

Assembly operations that involve humans can be characterized by the random and uncertain behavior of the agents involved. This leads to unpredictable changes in the occurrence of events over time. In this probabilistic context, the collaborative state must be continuously integrated into the system’s response in terms of both what to execute and when to execute it.4. Optimization Techniques

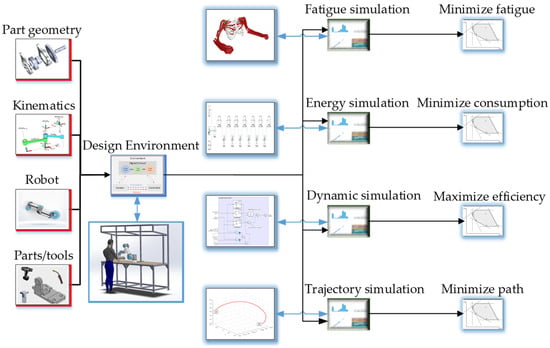

Manual operations cannot satisfy the demand for repeated human movements under load in collaborative assembly. Therefore, mathematical models could provide guidelines for making effective decisions within the current insufficient knowledge of the shared assembly tasks. Indeed, assembly task planning can be categorized as a particular optimization problem. One of the challenges in collaborative operations is the minimization of the cycle time, irrespective of the variability of the manual processing time in executing the assembly tasks as compared to automation [14][96]. When it comes to manufacturing, the first problem is concerned with task allocation and modeling, for which mathematical models and computer languages can provide the quantitative description of tasks to be performed [1][41]. The optimization of task allocation considering various modalities such as the part geometry, robot model and kinematics, as shown in Figure 29.

Figure 29. Optimization planning of task allocation for human–robot collaboration. Multi-criteria optimization for minimizing the human fatigue, energy consumption and path and maximizing efficiency.

Table 13. Optimization methods for HRC in the recent literature.

| Year | Ref. | Description/Title | ALBP | AD | MM | OT | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | [26][25] | Robot adaptation to human physical fatigue in human–robot co-manipulation |

✔ | DMP | Proposes a new human fatigue model in HRC based on the measurement of EMG signals. | ||

| 2019 | [27][55] | Sequence Planning Considering Human Fatigue for Human–Robot Collaboration in Disassembly | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | DBA | Solved the sequence planning considering human fatigue in human–robot collaboration using a bee algorithm. |

| 2019 | [28][31] | A selective muscle fatigue management approach to ergonomic human–robot co-manipulation | ✔ | ML | Performed experiments on two different HRC tasks to estimate individual muscle forces to learn the relationship between the given configuration and endpoint force inputs and muscle force outputs. |

||

| 2020 | [29][100] | Mathematical model and bee algorithms for the mixed-model assembly line balancing problem with physical human–robot collaboration |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | MILP BA ABC |

The authors presented a mixed-model assembly line balancing problem using a combination of MILP, BA and ABC algorithms. To this end, the proposed model and algorithm offer a new line design for increasing the assembly line efficiency. |

| 2020 | [30][101] | Bound-guided hybrid estimation of the distribution algorithm for energy-efficient robotic assembly line balancing |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | BGS | The authors proposed a bounded guided sampling method as a multi-objective mathematical model for solving the problem of the energy efficiency of robotic assembly line balancing. |

| 2020 | [15][97] | Scheduling of human–robot collaboration in the assembly of printed circuit boards: a constraint programming approach |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | MILP CP |

A comparison between MILP and CP reveals that CP offers a superior computational performance for ALBP, comprising between 60 and 200 task. |

| 2020 | [18][22] | Balancing of assembly lines with collaborative robots | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | MILP GA |

The authors developed a genetic algorithm to minimize the assembly lines’ cycle times for a given number of stations with collaborative robots. |

| 2021 | [19][61] | Balancing collaborative human–robot assembly lines to optimize the cycle time and ergonomic risk | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | MILP CP BD |

Human–robot collaboration was studied for sensitivity analysis. MILP, CP and BD algorithms were developed to analyze the benefits of human–robot collaboration in assembly lines. To this end, regression lines can help managers determine how many robots should be used for a line. |

| 2022 | [2][26] | A reinforcement learning method for human–robot collaboration in assembly tasks |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | RL | The use of reinforcement learning to optimize the task sequence allocation in the HRC assembly process. A visual interface displays the assembly sequence to the operators to obey the decision of the human agent. |

| 2022 | [31][13] | A dynamic task allocation strategy for mitigating the human physical fatigue in collaborative robotics | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | DNN | A non-intrusive online fatigue algorithm that predicts the joint muscle activation associated with the human motion. The estimation process allocates the task activities based on a sophisticated musculoskeletal model and a 3D vison system that tracks the human motion in real time. |

| 2022 | [32][12] | Development of an integrated virtual reality system with wearable sensors for the ergonomic evaluation of human–robot cooperative workplaces | ✔ | Ergonomic analysis strategy of humans in the loop virtual reality technology. The system uses a mixed- prototyping strategy involving a VR environment, computer–aided design (CAD) objects, wearable sensors and human subjects. |

Notes—ALBP: Assembly line balancing problem; AD: Algorithm development; MM: Mathematical modeling; OT: Optimization tool; DMP: Dynamic movement primitive; DBA: Discrete bee algorithm; ML: Machine learning; MILP: Mixed-integer linear programming; BA: Bee algorithm; ABC: Artificial bee colony; BGS: Bounded guided sampling; CP: Constraint programming; GA: Genetic algorithm; BD: Bender decomposition; RL: Reinforcement learning; DNN: Deep neural network.

With the widespread adoption of the digital human model (DHM), the realism and effectiveness of virtual manufacturing planning now enable the experiment of complex process assessments such as motion control and postures prediction. From the static postures of the DHM in the virtual environment, the designers can interpolate key postures to generate a continuous movement [39][106]. This can be achieved by inserting the anthropometric data of targeted users into a computer-generated environment for the virtual ergonomic evaluation of the human fit with the workstation [40][41][107,108].

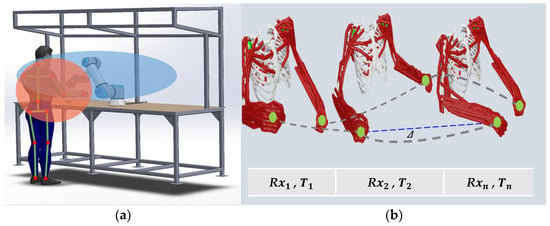

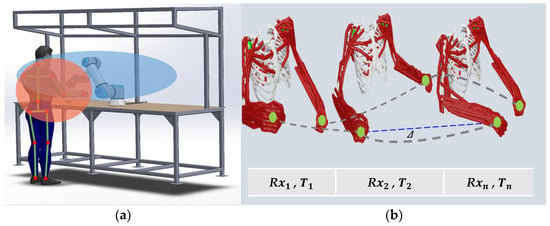

The integration of biomechanical parameters enables the evaluation of various workload scenarios within the simulation of the DHM. Because it is impractical to infer all functions of a real human, DHMs are generated with simplified features according to specific needs. It may therefore be necessary to model a set of specific postures. During the planning of human–robot collaborative systems for the analysis of physical fatigue, a DHM is used as the complementary agent for the upper body motion study in the interaction with the virtual collaborative robot, as shown in Figure 411. Once the data from the iterative analysis of the postural risks Rxn at times Tn and the desired motion patterns are acquired, the computation of the training data follows for the robotic interaction controller that identifies the variation (∆) in motion patterns.

With the widespread adoption of the digital human model (DHM), the realism and effectiveness of virtual manufacturing planning now enable the experiment of complex process assessments such as motion control and postures prediction. From the static postures of the DHM in the virtual environment, the designers can interpolate key postures to generate a continuous movement [39][106]. This can be achieved by inserting the anthropometric data of targeted users into a computer-generated environment for the virtual ergonomic evaluation of the human fit with the workstation [40][41][107,108].

The integration of biomechanical parameters enables the evaluation of various workload scenarios within the simulation of the DHM. Because it is impractical to infer all functions of a real human, DHMs are generated with simplified features according to specific needs. It may therefore be necessary to model a set of specific postures. During the planning of human–robot collaborative systems for the analysis of physical fatigue, a DHM is used as the complementary agent for the upper body motion study in the interaction with the virtual collaborative robot, as shown in Figure 411. Once the data from the iterative analysis of the postural risks Rxn at times Tn and the desired motion patterns are acquired, the computation of the training data follows for the robotic interaction controller that identifies the variation (∆) in motion patterns.

Given the stream of continuous movements that moving systems exhibit during their daily routine, a fundamental question that remains is to determine the initial blocks that, looped together, build and execute the motion controls of both artificial and biological entities [42][109]. The authors in [4][42] discuss the previous limitation of simulation software for collaborative assembly lines to the modeling of plain action sequences. Progress in virtual technology now enables 3D simulation to automatically generate a work cell with the allocation of tasks between the human and the robot resources [43][75]. The conceptual simulation in [12][49] improved the cycle time, ergonomic factor and human utilization in the collaboration modes presented and proved the possibility of HRC application in the mold assembly.

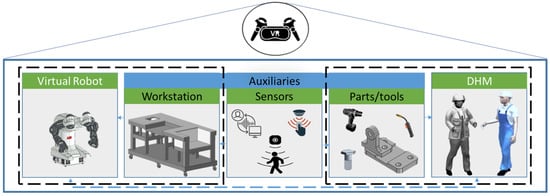

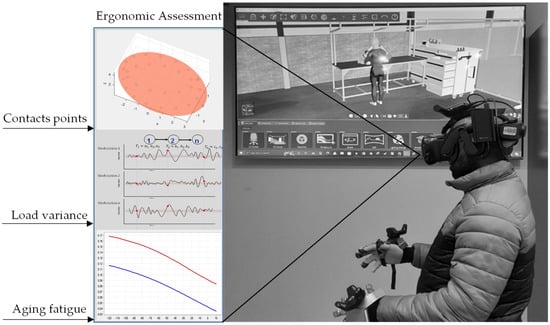

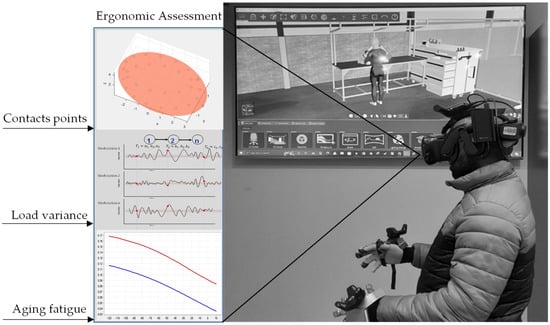

The authors in [32][12] proposed a novel collaborative assembly design strategy based on virtual reality for ergonomic assessment. The system was made up of four key components: virtual reality devices for the human immersion and interaction, a robotic simulator for modeling the robot in the working environment, surface EMG sensors and accelerometers for measuring the human ergonomic status. After applying the system to a real industrial use-case related to a human–robot task in the automotive industry, it was found that the methodology can effectively be applied in the analysis of physical conditions in human–robot interaction. This was to endow the co-worker with self–awareness with respect to their ergonomic status and safety conditions while the co-worker directly performs the task in the immersive virtual environments. A similar virtual collaborative task-planning set-up is shown in Figure 512.

Given the stream of continuous movements that moving systems exhibit during their daily routine, a fundamental question that remains is to determine the initial blocks that, looped together, build and execute the motion controls of both artificial and biological entities [42][109]. The authors in [4][42] discuss the previous limitation of simulation software for collaborative assembly lines to the modeling of plain action sequences. Progress in virtual technology now enables 3D simulation to automatically generate a work cell with the allocation of tasks between the human and the robot resources [43][75]. The conceptual simulation in [12][49] improved the cycle time, ergonomic factor and human utilization in the collaboration modes presented and proved the possibility of HRC application in the mold assembly.

The authors in [32][12] proposed a novel collaborative assembly design strategy based on virtual reality for ergonomic assessment. The system was made up of four key components: virtual reality devices for the human immersion and interaction, a robotic simulator for modeling the robot in the working environment, surface EMG sensors and accelerometers for measuring the human ergonomic status. After applying the system to a real industrial use-case related to a human–robot task in the automotive industry, it was found that the methodology can effectively be applied in the analysis of physical conditions in human–robot interaction. This was to endow the co-worker with self–awareness with respect to their ergonomic status and safety conditions while the co-worker directly performs the task in the immersive virtual environments. A similar virtual collaborative task-planning set-up is shown in Figure 512.

Given the recent development in the fields of vision sensors, VR as a synthetic environment can be used to handle some of the engineering and testing problems in machine vision (MV). It has become possible to develop frameworks for human–robot teams to work collaboratively through gesture recognition [44][71]. A priori, virtual reality and computer vision may seem to be research areas in HRC, with opposite objectives. Yet, human situational parameters can be monitored with fixed systems such as cameras, and through cognitive enablers, smart actuators can provide triggers to change the system state (flow) if the operator pace is downgrading due to fatigue [45][2]. In the simulated environment, MV provides the enablers needed to implement intelligent creatures within the virtual environment. In the immersive test environment, MV captures the sensing information of the real human in terms of movement pace. Then, the behavior of the virtual robot is positioned and arranged as the human situation changes.

Given the recent development in the fields of vision sensors, VR as a synthetic environment can be used to handle some of the engineering and testing problems in machine vision (MV). It has become possible to develop frameworks for human–robot teams to work collaboratively through gesture recognition [44][71]. A priori, virtual reality and computer vision may seem to be research areas in HRC, with opposite objectives. Yet, human situational parameters can be monitored with fixed systems such as cameras, and through cognitive enablers, smart actuators can provide triggers to change the system state (flow) if the operator pace is downgrading due to fatigue [45][2]. In the simulated environment, MV provides the enablers needed to implement intelligent creatures within the virtual environment. In the immersive test environment, MV captures the sensing information of the real human in terms of movement pace. Then, the behavior of the virtual robot is positioned and arranged as the human situation changes.

5. Digital Interface

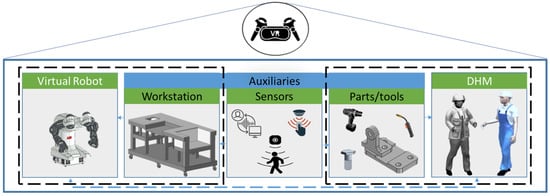

Previous research has focused on using computer modeling to better identify the system requirements for human–machine task analysis. A way to quickly and safely design and test a manufacturing process such as HRC is by utilizing a virtual space. In Hernández, Sobti [33][69], motion planning in an augmented reality (AR) interface increased the robot’s autonomy and decision-making capabilities, thereby allowing the human to make more general and open requests. Matsas, Vosniakos [34][102] positively judged the application of virtual reality (VR) for the experimentation of complex interaction metaphors, especially for the use of cognitive aids. The experiments in [35][36] demonstrated the feasibility of pHRI through a VR approach in which the operator achieves the necessary comfort functions. Computer simulation is also used to map a digital counterpart of an HRC work environment in [36][37][103,104]. Digital twins help establish each entity in the virtual space, whereby the physical assembly space is driven by real-time simulation, analysis and decision making of the mapping process [20][5]. Malik, Masood [5][43] developed a unified framework for integrating human–robot simulation with VR as an event-driven simulation to estimate the H–R cycle times and develop a process plan, layout optimization and robot control. Ji, Yin [38][105] presented a novel programming-free automated assembly planning and control approach based on virtual training. The variety of goals contained within an HRC assembly system requires special applications for the modeling, simulations and predictive visualization of the collaborative system’s performance. VR and AR offer the interface in which multiple scenarios and components can be configured and tested, as shown in Figure 310.

Figure 310. Components of a virtual HRC assembly design. CAD models of humans, collaborative robots and tools are imported into an immersive environment where interaction is enabled through sensors. Such environments allow for the relative safety of testing multiple interaction scenarios prior to physical set-ups.

Figure 411. (a) Co-assembly areas of the human (orange) and robot (blue), (b) Biomechanical modeling of upper-body motion patterns. The motion patterns of the upper-body limbs are cataloged, and the visual controller can evaluate the deviations from the prescribed path(s) in both space and time.

Figure 512. Virtual collaborative assembly design. The development is performed at the X-Reality Lab, RMCERI, Department of Industrial Engineering, TUT. The protocols are designed to enable the co-operator to view the ergonomic characteristics of the assembly task in terms of the contact points in space between the human, the robot and the product, the load variance at various execution times and the aging energy level.