This entry compiles information on biopolymers and natural bioactive compounds used in the production of bioactive films. Particular emphasis has been given to the methods used for incorporating bioactive compounds into film-forming solutions and their influence on the functional properties of biopolymer films.

This study compiles information on biopolymers and natural bioactive compounds used in the production of bioactive films. Particular emphasis has been given to the methods used for incorporating bioactive compounds into film-forming solutions and their influence on the functional properties of biopolymer films.

- food packaging

- antioxidant activity

- antimicrobials

- natural compounds

- biopolymers

- agricultural products

- agricultural products.

1.

Plastic, usually derived from non-renewable sources, is among the most used materials in food packaging. Despite its barrier properties, plastic packaging has a recycling rate below the ideal and its accumulation in the environment leads to environmental issues. One of the solutions approached to minimize this impact is the development of food packaging materials made from polymers from renewable sources that, in addition to being biodegradable, can also be edible. Different biopolymers from agricultural renewable sources such as gelatin, whey protein, starch, chitosan, alginate and pectin, among other, have been analyzed for the development of biodegradable films. Moreover, these films can serve as vehicles for transporting bioactive compounds, extending their applicability as bioactive, edible, compostable and biodegradable films. Biopolymer films incorporated with plant-derived bioactive compounds have become an interesting area of research. The interaction between environment-friendly biopolymers and bioactive compounds improves functionality. In addition to interfering with thermal, mechanical and barrier properties of films, depending on the properties of the bioactive compounds, new characteristics are attributed to films, such as antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, color and innovative flavors. (Draft for Definition)

Introduction

Most food packaging is produced from synthetic materials from non-renewable sources, which, despite having excellent barrier and resistance properties, are causing serious environmental problems due to the generation of high amounts of non-degradable solid waste[1] [1]. However, the use of packaging is essential. Apart from its basic function of containing the food, it also plays a fundamental role in controlling interactions between food and the environment, protecting and helping to maintain product quality[2][3] [2,3].

This factor, along with environmental concerns, in combination with consumer demands for high quality eco-friendly products that are related to those found in nature (natural products) have driven the development of new technologies, such as the production of biodegradable films from polymers from renewable sources[1][2][4] [1,2,4], for the development of packaging materials.

The biodegradability of plastic materials is defined as their ability to decompose through the enzymatic action of microorganisms[5] [5]. The polymer degradation in a bioactive environment occurs by material fragmentation and subsequent mineralization. The action of heat and moisture as well as enzymatic activity of microorganisms abbreviate and fade the polymer chains, resulting in fragmentized residues of the polymer. These polymer fragments can only be considered biodegradable if they are consumed by microorganisms as food and energy source converted at the end of the degradation process into carbon dioxide (CO2), water (H2O) and biomass under aerobic conditions and hydrocarbons, methane and biomass under anaerobic conditions[6] [6].

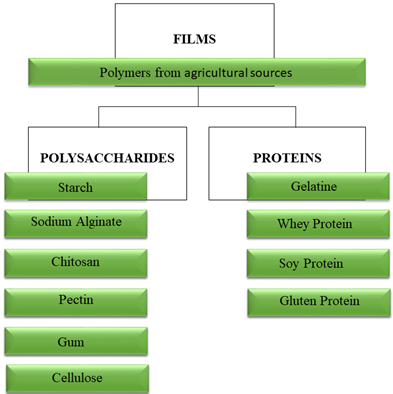

Polysaccharides, such as starch[7][8][9] [7–9], cellulose[1][2] [1,2] alginate sodium[3][10] [3,10], pectin[4][11] [4,11], chitosan[8][12] [8,12], gums[13][14][15] [13–15]; and proteins, such as whey[10][16] [10,16], soy[17][18] [17,18], gluten[19][20][21] [19–21] and gelatine[10][19][22][23] [10,19,22,23] are among the most employed biopolymers in the development of biodegradable films. These natural biopolymers are commonly used due to their abundance in nature, biodegradability and edibility. Among these natural biopolymers, starch stands out for its easy processing and low cost[1][7][8][24] [1,7,8,24]. Among the techniques used for the production of these films, there are casting, pressing and extrusion followed by blowing[23] [23].

In addition to biopolymers, plant-derived bioactive compounds such as essential oils, vitamins, minerals, polyphenols, carotenoids, among others, are widely distributed in nature. Different parts of plants, such as leaves, flowers, seeds and roots can potentially be used in the production of environment-friendly films with functional properties due to their biological nature[25] [25]. Some bioactive compounds have antioxidant[26][27] [26,27] and antimicrobial activity[3][27][28] [3,27,28].[29][30][31][32][33]

The combination of biopolymers with natural bioactive compounds has enabled the development of bioactive films with new and/or improved properties, i.e., antioxidant[26][27] [26,27] and antimicrobial[3][27][28] [3,27,28] effect, innovative colors[11][34] [11,29], and customized barrier and mechanical properties[11][34][35] [11,29,30].

The incorporation of bioactive compounds into biodegradable films has been extensively studied[3] [9][28][34][29][30][3,9,28,29,31,32]. The use of inherently bioactive biopolymer-based materials[31][32][33] [33–35] as well as the incorporation, direct or by sprinkling, of free or encapsulated bioactive compounds into the film-forming solutions[26][34] [26,29] are some of the techniques employed for their production.

The application of bioactive films in packaging as a strategy for extending the shelf life, stability and safety of food products has shown great potential[36][37][38] [36–38]. In the food industry, microbial deterioration and lipid oxidation are major problems to be overcome in order to increase the shelf life of food products[25] [25]. The release of bioactive compounds from films into foods prevents the oxidation of lipid compounds present in their composition[37] [37], as well as the growth of microorganisms[38] [38], improving their shelf life. Thus, the use of natural bioactive compounds in biodegradable films has proved to be a potential alternative for solving this problem in the food industry and for replacing traditional packaging[25] [25]. Previous review papers have summarized the most recent trends on the strategies used for stabilizing bioactive compounds for inclusion in packaging materials[39] [39] and for release control of active compounds from food active packaging systems [40]. Given the relevance and scope of the topic and the large amount of scientific research addressing the incorporation of bioactive compounds in films, more review articles are still needed. According to all the facts, this article provides an overview of the types of agro-based polymers from renewable sources and plant-derived bioactive compounds used, as well as the latest trends on methods used for their inclusion in biodegradable films. In addition, an in-depth description of each method of producing bioactive films and their functional properties is presented.

2. Main Agro-Based Polymers from Renewable Sources Used in the Development of Biodegradable Film

Environmental concerns regarding the disposal of non-biodegradable materials, and in accordance with the circular economy values, include: use of renewable sources, preservation of fossil raw materials, landfill waste reduction and carbon dioxide (CO2) emission reduction. Several studies involving biodegradable polymers of agricultural origin (Figure 1) with lipids, plant-based proteins (zein, soy, pea, gluten), animal-based proteins (gelatin, whey, casein), and polysaccharides (starch, chitosan, sodium alginate, pectin, gums (and ligno-cellulosic (straws and wood)) are emerging.

Figure 1. Main polymers of agricultural origin from renewable sources used in the development of biodegradable films.

Some characteristics and properties of these biopolymers of agricultural origin have been reported. The most abundant organic compound in nature is cellulose, its derivatives with the methylcellulose, hydroxypropylmethylcellulose and carboxymethylcellulose are widely used as raw materials that form edible films, as they are naturally odorless and tasteless[41] [41]. However, cellulose derivative films showed poor properties as a barrier to water vapor due to their hydrophilicity[42] [42]. Likewise, films produced with Carrageenan gum exhibited limitations regarding their water vapor permeability and water resistance[43] [43]. Gums are another group of polysaccharides that have been used as film forming agents and are produced naturally by some botanical (trees and shrubs, seeds and tubers), algae (red and brown algae) or microbial sources[44] [44].

Starch, a polysaccharide composed of two macromolecules, amylose and amylopectin, is used in its native and modified form. In addition, due to different proportions of amylose and amylopectin present in different starch sources, unconventional starch sources have been increasingly used in the production of edible films, such as arrowroot starch[9] [9] and black rice starch[45] [45]. The two components can be separated, allowing new blends with other proportions and, thus, increasing their use[46] [46]. Starch has high amylose content, a desirable feature for the production of films with good technological properties and stronger and more flexible mechanical characteristics[47] [47]. Corn, potato, rice, wheat and cassava starches are the most commercially used[48] [48].

Alginate and pectin are anionic polysaccharides. Pectin is derived from the plant cell wall and it is obtained commercially by aqueous extraction of pectic material from some fruits, being found in higher amounts in citrus fruits and apples[49] [49]. It consists mainly of the methoxy esterified α, d-1, 4-galacturonic acid units[50] [50]. Alginate is composed of β-d-manuronic acid and α-l-guluronic acid, joined linearly by α-1,4 glycosidic bonds, obtained from cell walls of brown algae[51] [51]. Both biopolymers are widely applied in the food industry for being able to form gels with the presence of divalent cations, such as calcium ions. Moreover, they are able to create biodegradable edible films with measurable characteristics[52] [52]. The combination of both polysaccharides generated continuous, homogenous and transparent films[53] [53]. The addition of alginate into pectin-based formulations improved the strength of zinc ions crosslinking network[54]. Chitosan (poly (1,4-β-d-glucopyranosamine)), is a biodegradable cationic polymer derived from chitin, a polysaccharide of animal origin. Chitosan shows antimicrobial properties[55] [55] and the ability to form films[56] [56]. According to Vargas et al.[56] [56], due to its high to water vapor permeability, its barrier properties can be improved by its combination with other hydrocolloids. Chitosan is an ideal biopolymer for the development of antimicrobial films due to its non-toxicity[57] [57], biocompatibility[58] [58], biodegradability and intrinsic antimicrobial action.

The most widely used proteins in the production of edible films are gelatin[19][23] [19,23], whey protein isolate[59] [59], soy [17][18][17,18] and gluten[19][20][21] [19–21]. Gelatine is classified and commercialized according to its strength, or “bloom”[60] [60]. “Bloom” and viscosity are the main rheological characteristics of gelatine and are usually the result of the manufacturing process applied. The viscoelastic properties are related to the amino acid composition, average molecular weight and the degree of polymerization of the chain[61] [61]. There are reports of the use of gelatine type A [23] and type B[62] [62]. Gelatine forms films with high transparency and good tensile strength; in order to improve its mechanical properties, blends with different hydrocoids are widely used[19][63] [19,63].

Bovine milk whey is a by-product of the dairy industry. It represents the aqueous portion of milk that separates from the clot during cheese making or casein production and consists of a complex mixture of globular proteins (~0.6%), lipids, minerals and lactose, in water (93%)[64] [64]. Drying and removing non-protein components from whey leads to commercial products such as concentrates (whey protein concentrate—WPC, with 25 to 80% proteins) or isolates (whey protein isolate—WPI, with proteins concentration ≥90%) of whey proteins, which are widely used in the food sector due to their functional properties as gelling agents, emulsifiers and foam stabilizers[65] [65].

Whey protein isolate (WPI) has the ability to form films with a wide range of functional properties depending on their structural cohesion[59] [59]. Native WPI films presented rapid water dissolution, showing favorable edible characteristics[59] [59]. Films produced with heat-denatured WPI (HWPI) proved to be water-insoluble with good mechanical properties and excellent oxygen, aroma and oil barrier properties at relative low humidity[66] [66]. Wheat gluten is a general term for water-insoluble proteins separated from wheat flour. It consists of a mixture of peptide molecules considered globular proteins. The cohesiveness and elasticity of gluten produce integrity and facilitate the formation of films[67] [67]. Gluten can be obtained by pressing an aqueous mass of wheat flour and gently washing the starch and other soluble materials in a dilute acid solution or in an excess of water. It can be separated into two fractions: (i) gliadin, soluble in 70% ethanol, and (ii) glutenin, insoluble in ethanol[68] [68]. These authors made films based on wheat gluten and obtained high elongation values. Gontard et al.[69] [69] studied the addition of various concentrations of lipids into edible gluten films developed by the casting technique as barrier components to water vapor permeability. The effects of this addition depended on the characteristics of the lipids and their interactions with the protein structural matrix.

Soy protein isolate (SPI) is a byproduct of the soybean oil industry, it comprises a set of macromolecules of varied sizes and structures formed from 18 different amino acid residues, being constituted by the soy storage proteins [70]. Due to its availability, environmentally friendly nature and excellent film-forming property, soy protein isolate has been widely accepted for exploitation in protein-based films[71] [71]. SPI-based film usually shows lower permeability oxygen (O2) behavior in comparison to films based on low-density polyethylene, methylcellulose, starch and pectin. According to a study by Giacomelli[70] [70] on thermal and morphological properties of films made with soy protein isolate, the thermal degradation of these films occurs in a single step, starting at 292 °C. However, due to their high hydrophilicity, films do not present satisfactory mechanical properties or a water vapor barrier for applications such as packaging[72] [72].

Despite the promising characteristics of edibility, biocompatibility and biodegradability presented by polymer from agricultural sources, it is still evident that there are limitations to be overcome for the commercial success of these films (mainly low elongation, low resistance to gases and liquids), especially when compared to synthetic plastics [73]. In general, it is noted that films produced from polysaccharides tend to have a good barrier against gases, but have low resistance to water vapor and low mechanical resistance, while the films produced from proteins also have low resistance to water vapor, but good mechanical resistance[73] [73].

In addition, most films made from polymers of agricultural origin are obtained on a laboratory scale, using the casting method. This method is based on the dispersion of macromolecules into a suitable solvent or mixture of solvents, thus obtaining the film-forming suspension that is subjected to thermal gelatinization. The resulting solution is deposited in molds of relatively small sizes (90 mm × 15 mm [11]; 14 cm × 14 cm[74] [74]; 12 cm diameter [26]; 14.3 cm diameter[30] [30]) for drying and solvent removal. In order for the properties of the resulting films not to be negatively affected, low temperatures (around 25 °C to 45 °C [3,11,74,75]) are required in the drying step, leading to long drying times (2–3 days). The difficulty of making films of large size (>25 cm), with precise thickness (local variations in thickness) and short drying times, make current methods of manufacturing laboratory-scale films unsuitable for expansion into industrial production[73] [73].

3. Most Common Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds Incorporated into Biodegradable Films for Development of Bioactive Films

In recent years, bioactive compounds have attracted the attention of scientists, researchers and the world’s population, as their consumption has been associated with beneficial effects on physical and mental health because they provide crucial biological effects in the prevention and treatment against a wide range of diseases. Some bioactive compounds have antimicrobial[2][12][25] [2,12,25], antioxidant[12][37][75] [12,37,75], anticancer, anti-inflammatory and/or anti-neurodegenerative activities[76] [76].

Widely distributed in nature, bioactive compounds are mainly secondary metabolites of plants, presenting both nutritional value and other functions in their metabolism, such as a growth stimulator and a protector against biotic and abiotic stress[77] [77].

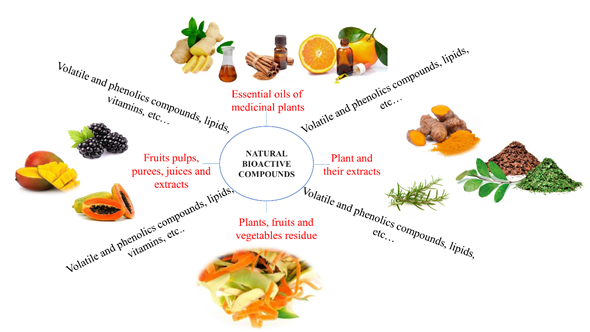

Leaves, flowers[3] [3], fruits, vegetables[11] [11], seeds, grains[31][78] [31,78], rhizomes and roots[32] [32], of various types of plants are good sources of diversified bioactive compounds including phenols, essential oils, proteins, terpenoids and flavonoids, among others (Figure 2), as listed:

- plants and their extracts as a source of phenolic compounds: of Plantago lanceolata, Arnica montana, Tagetes patula, Symphytum officinale, Calendula officinalis and Geum urbanum[79]; turmeric[32]; Acca sellowian[80] [80]; Chinese chive root[27]; tea polyphenol [28]; rosemary[81]; yerba mate[82]; jujube leaf[83];

- essential oils from medicinal plants as a source of volatile and phenolics compounds and lipids: M. pulegium L., A. Herba alba Asso, O. basilicum L. and R. officinalis L. [3]; green coffee beans (Coffea arabica L.[31]); thyme essential oil[84]; Ziziphora clinopodioides essential oil[85]; orange essential oil[86]; cinnamon leaf essential oil[13]; black pepper essential oil and ginger essential oil[87]; rosemary essential oil[88]; Satureja Khuzestanica essential oil[89];

- fruit pulps, purees, juices and extracts as a source of phenolic compounds and vitamins: guabiroba[74]; blackberry[26], pomegranate [90]; açai[91]; papaya[92], blueberry[93]; mango; acerola; seriguela[94]; anthocyanins from jambolan fruit (Syzygium cumini)[95]; mulberry anthocyanin extract[96]; papaya puree[97]; mango and acerola pulps[98]; acerola[99].

- plants, fruits and vegetables residue flour or extract: sweet orange (Citrus sinensis), passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), whereas the vegetables were zucchini (Cucurbita pepo), lettuce (Lactuca sativa), carrot (Daucus carota), spinach (Spinacea oleracea), mint (Menthas p.), yams (Colocasia esculenta), cucumber (Cucumis sativus) and arugula (Eruca sativa) [11]; pomelo peel flours [28], Acca sellowiana waste by-product (feijoa peel flour, [80]); roasted peanut skin extract[100]; pine nut shell, peanut shell[83]; ethanolic red grape seed extract[85].

- plants and their extracts as a source of phenolic compounds: of Plantago lanceolata, Arnica montana, Tagetes patula, Symphytum officinale, Calendula officinalis and Geum urbanum [79]; turmeric [32]; Acca sellowian [80]; Chinese chive root [27]; tea polyphenol [28]; rosemary [81]; yerba mate [82]; jujube leaf [83];

- essential oils from medicinal plants as a source of volatile and phenolics compounds and lipids: M. pulegium L., A. Herba alba Asso, O. basilicum L. and R. officinalis L. [3]; green coffee beans (Coffea arabica L. [31]); thyme essential oil [84]; Ziziphora clinopodioides essential oil [85]; orange essential oil [86]; cinnamon leaf essential oil [13]; black pepper essential oil and ginger essential oil [87]; rosemary essential oil [88]; Satureja Khuzestanica essential oil [89];

- fruit pulps, purees, juices and extracts as a source of phenolic compounds and vitamins: guabiroba [74]; blackberry [26], pomegranate [90]; açai [91]; papaya [92], blueberry [93]; mango; acerola; seriguela [94]; anthocyanins from jambolan fruit (Syzygium cumini) [95]; mulberry anthocyanin extract [96]; papaya puree [97]; mango and acerola pulps [98]; acerola [99].

- plants, fruits and vegetables residue flour or extract: sweet orange (Citrus sinensis), passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), whereas the vegetables were zucchini (Cucurbita pepo), lettuce (Lactuca sativa), carrot (Daucus carota), spinach (Spinacea oleracea), mint (Menthas p.), yams (Colocasia esculenta), cucumber (Cucumis sativus) and arugula (Eruca sativa) [11]; pomelo peel flours [28], Acca sellowiana waste by-product (feijoa peel flour, [80]); roasted peanut skin extract [100]; pine nut shell, peanut shell [83]; ethanolic red grape seed extract [85].

Figure 2. Examples of plant-derived bioactive compounds.

Plant-derived bioactive compounds are being considered interesting ingredients for the production of biodegradable and bioactive films due to their natural origin and functionality[25] [25]. Studies have shown that the incorporation of plant extracts and fruit pulps as sources of bioactive compounds or isolated bioactive compounds into film-forming solutions cause antioxidant and antimicrobial effects on the resulting films, extending their application in bioactive and biodegradable films or packaging[2][3][12][27][36][101] [2,3,12,27,36,101]. Recently, Benbettaïeb et al.[102] [102] carried out an in-depth review on the mechanisms involved in the antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of edible bioactive films for food applications.