Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Javier Ramirez Jirano and Version 2 by Lindsay Dong.

The main histopathological hallmarks of Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the degeneration of the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta and the loss of neuromelanin as a consequence of decreased dopamine synthesis. The destruction of the striatal dopaminergic pathway and blocking of striatal dopamine receptors cause motor deficits in humans and experimental animal models induced by some environmental agents. In addition, neuropsychiatric symptoms such as mood and anxiety disorders, hallucinations, psychosis, cognitive impairment, and dementia are common in PD. These alterations may precede the appearance of motor symptoms and are correlated with neurochemical and structural changes in the brain.

- Parkinson’s disease

- pathophysiology

- genetics

- psychiatric illness

- cognitive dysfunction

- neuropsychological tests

1. Introduction

In 1817, the English physician James Parkinson published the first clinical essay on “paralysis agitans”, a term by which he defined the disease, and he reported six cases characterized by involuntary tremor movement with decreased muscular strength in passive and active mobility and with an increased forward inclination of the trunk [1]. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s [2]. Its neurological basis remained unknown for more than a hundred years, while histopathological examinations of brains with PD showed an significant loss of nerve cells of the substantia nigra. The term substantia nigra derives from the fact that its cells appear dark due to the neural pigment in them called neuromelanin. These pigmented cells are lost in PD, and an even more critical aspect is that this set of cells uses dopamine as their primary neurotransmitter. This cell degeneration is accompanied by a severe reduction (more than 80%) in the dopamine content in the striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), the point of greatest termination of the axons from the substantia nigra [3].

Progressive damage to the ascending dopaminergic system, in particular to the nigrostriatal pathway, which is mainly responsible for the motor disorders of PD, is based on the following:

-

Motor parkinsonian symptoms begin to appear when striatal dopamine levels are reduced between 70% and 80% of normal levels, which approximately corresponds to a loss of 50% of the total synapses of the substantia nigra towards the striatum, which is the central nucleus of input of motor information from the cortex towards the basal nuclei, fed back by nigrostriatal pathways to modulate movement through motor anagrams (chunks of motion information) stored in the basal ganglia.

-

This threshold is directly related to the appearance of symptoms: there is a correlation between the extent of damage to the dopaminergic system and the severity of the symptoms because neuronal destruction gradually produces a progressive deficit of dopamine in the striatum, which induces a significant loss of voluntary or involuntary spontaneous movement.

-

Destruction of the striatal dopaminergic pathway and blocking of striatal dopamine receptors cause motor deficits similar to those observed in PD, both in humans and experimental animals induced with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OH-DA), reserpine, or methamphetamine.

-

Drug therapies that cause an increase in dopamine availability or stimulate dopamine receptors at the level of the striatum reduce the symptoms associated with this deficit, mainly motor ones [4].

PD affects the dopaminergic system and the serotonergic, glutamatergic, and GABAergic. This results in motor disorders, but also various non-motor functional diseases. The main typical symptoms and definition of PD are a deceleration in movement (bradykinesia) as well as increased muscle tone (rigidity), and tremors at rest [5]. The axial bradykinesia and rigidity are associated with the typical posture, gait, and balance issues that affect PD patients over time.

PD cannot be reduced to its motor manifestations. In recent years, interest in the neurocognitive, psychiatric, and neuropsychological disorders of PD has developed considerably. PD represents a preponderant area of neuropsychiatry for symptomatic manifestations and neurophysiopathology. Some people experience depressive syndromes before the onset of motor symptoms; others develop psychiatric symptoms or syndromes simultaneously or after the beginning of motor symptoms. Others may develop iatrogenic behavioral disorders, such as dopaminergic dysregulation syndrome, punding associated with levodopa, and impulse control disorders underlying dopamine agonist intake [6][7][7,8].

The most frequent non-motor symptoms in PD are depression, anxiety, apathy, sleep disturbances, psychotic features, behavioral changes, and cognitive deficits [8][9]. For patients and relatives, these disorders are often more distressing and disabling than the motor aspects. The presence of depressive symptoms seems to be related to an earlier drop in dopaminergic synaptic power or associated iatrogenically with an abrupt discontinuation of dopaminergic therapy, as well as more significant functional disability, more rapid physical and cognitive decline, higher mortality, worsening quality of life, and greater suffering for caregivers. Depressive disorders are often underdiagnosed and, even if identified, are often not adequately treated [9][10]. The clinical overlap of some depressive and anxious dimensions with symptoms typical of parkinsonian pathology, with possible cognitive alterations and somatic symptoms, further complicates diagnosing neuropsychiatric symptoms.

However, the prevalence of depressive symptoms differs according to the clinical population studied, the depressive subtypes evaluated, and the heterogeneity in the syndromic presentation. Several prevalence studies have shown that less than half of patients reporting depressive symptoms have a definite diagnosis of major depression. The prevalence of dysthymia and minor depression is 22.5% and 36.6%, respectively [6][7]. For this reason, the term subsyndromic depression is introduced as the presence of depressive symptoms that do not fully meet the standardized diagnostic criteria for the different depressive disorders; for example, patients who display depressive symptoms only during “off” states may fit this definition [10][12].

After using deep brain stimulation (DBS) to treat motor symptoms, mood disturbances provide another window to study depression in PD. The risk of suicide, aggression, depression, and mania are among the most frequent psychiatric and behavioral complications after DBS treatment [11][14]. Indeed, it is hypothesized that subthalamic stimulation inhibits serotonergic transmission through the interconnections between the substantia nigra pars reticulata, medial prefrontal cortex, and ventral pallidum [12][15]. The presence of anxiety disorders in patients with PD is well documented. Although anxiety is often associated with depression, it can manifest independently and significantly affect patients’ quality of life; the prevalence rates shown range from 25% to 52% of patients [13][16].

Psychotic symptoms in PD are characterized mainly by hallucinations (primarily visual), delusions, and other sensory disturbances and occur in 20–40% of cases, negatively affecting patients’ quality of life. Psychotic symptoms are also often attributable to the use of antiparkinsonian drugs; however, it is increasingly recognized that the underlying pathological process of PD plays an essential role in its pathogenesis and expression [14][15][17,18].

Cognitive, psychiatric, and neuropsychological disorders are essentially part of the alteration of the quality of life of patients and their caregivers. Depressive and anxiety syndromes, hallucinations and other “psychotic” symptoms, apathy, and impulse control disorders raise difficult pathophysiological questions and discussions around the factors related to premorbid vulnerability, disease, and its pharmacological or surgical treatments.

2. Pathogenic Factors

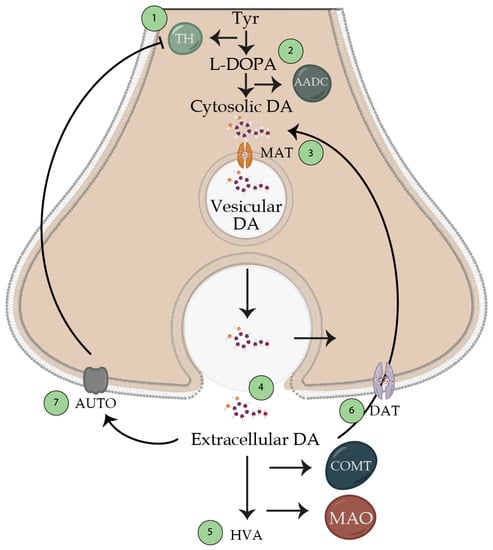

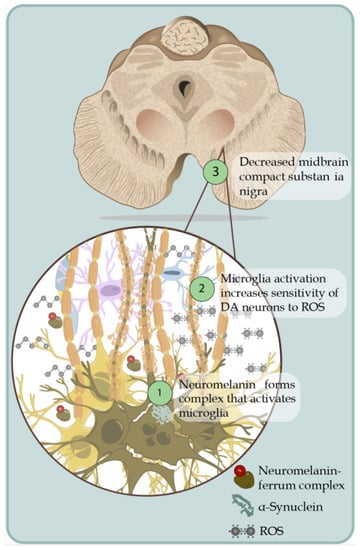

PD should be managed more like a syndrome, since pathological mutations are well-implicated with the disease in an autosomal dominant or a recessive way. Nevertheless, other mutations can generate lower susceptibility to PD to some extent, most likely depending on exposure to toxic or biological environmental agents that have not yet been well identified. The accumulation of different proteins in the central nervous system can express this. Future research and the demonstration of its relationship with specific genetics or environmental agents will truly clarify the diseases that make up this parkinsonian syndrome (Parkinson’s syndrome). A current theory suggests that dopaminergic neurons are damaged and eventually die due to chronic oxidative stress. The uncontrolled generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as anion superoxide, peroxynitrite, hydrogen peroxide, etc., causes severe damage to nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids [16][19]. The neurons of the substantia nigra are susceptible to oxidative stress in PD [17][20]. Environmental toxins such as paraquat, MPTP, and rotenone can destroy dopaminergic neurons currently used in animal models of PD [18][21] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Death of dopaminergic neurons. Schematic representation of dopaminergic neuronal death associated with the generation of ROS in an uncontrolled way. 1. The pigment that gives color to dopaminergic cells is due to the oxidation of cysteinyl-DA products (dopamine that is not adequately removed works as ROS-generating molecules), products that interact with Fe+ forming a complex that activates the microglia and thereby generates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the production of ROS, which induce the formation of alpha-synuclein fibrils. 2. Activation of microglia by the release of neuromelanin from pars compacta causes an increase in the sensitivity of dopaminergic neurons to oxidative stress; the dopaminergic neurons of the compact substantia nigra are more susceptible to ROS, which is why they more easily cause the death of this neuronal subpopulation in areas such as nuclei A9. 3. Decreased midbrain compact substantia nigra.

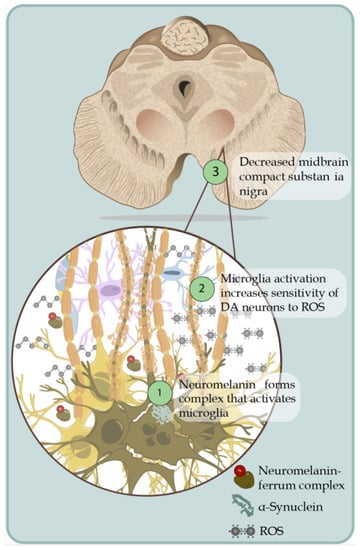

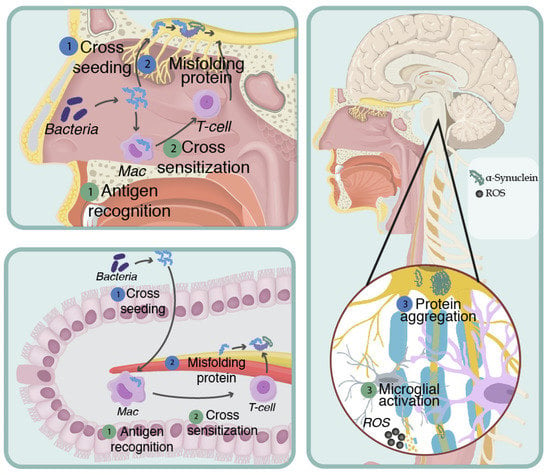

The early detection of abnormal alpha-synuclein deposits also in gastrointestinal extracerebral neurons (plexuses and ganglia) in PD patients gives new support to the exotoxic hypothesis. This, and the observation of the cauda–cranial dissemination of cognitive disorder with Lewy bodies in neurons of the CNS, beginning in the olfactory bulb and the neurons of the caudal part of the nucleus of the vagus nerve, constitute elements in favor of the entry of a causative agent through the nasal membrane or intestinal mucosa (gastrointestinal hypothesis) [19][23]. Additionally, PD could be another disease caused by an abnormally folded protein that spreads similarly to prions [20][24]. This hypothesis has recently caused a strong surge in PD research; while these data have not been fully demonstrated, recently, the gastrointestinal microbiome of PD patients made establishing a relationship with PD possible [21][25] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mapranosis. Schematic representation of Friedland and Trudler’s proposal to explain neurodegeneration. Amyloid is secreted by bacteria resident in the nasal and intestinal epithelium, which causes neuroinflammation in two ways: 1. Misfolded Protein 1.1. Bacterial amyloid can cross seed with host beta-amyloid and alpha-synuclein. 1.2. This cross seeding induces the wrong folding of the alpha-synuclein due to prionic behavior; therefore, it extends through the vagus and olfactory nerve. 1.3. The new poorly folded endogenous proteins it disseminates reaches the CNS, causing neuronal death. 2. Induction of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. 2.1. Bacterial amyloid is capable of inducing inflammation and oxidative stress. 2.2. Subsequently, there is cross sensitization against endogenous amyloid, which causes the immune system’s abnormal recognition of its epitopes, mounting a response directed against beta-amyloid and alpha-synuclein in the host’s CNS. 2.3. The sensitized immune cells reach the CNS through the hematogenous pathway, crossing the BBB, and activating the microglia, causing neuronal death.

3. Pathophysiology of Neuropsychiatric Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease

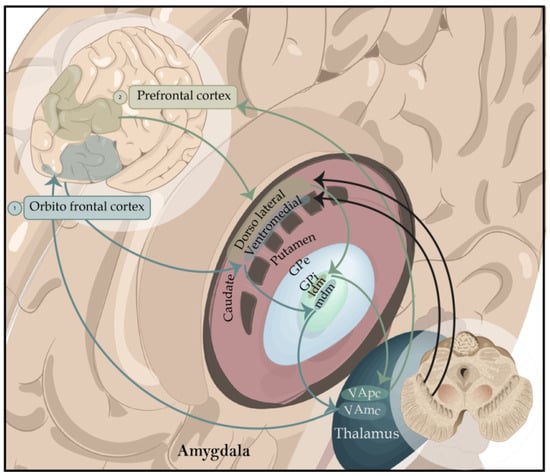

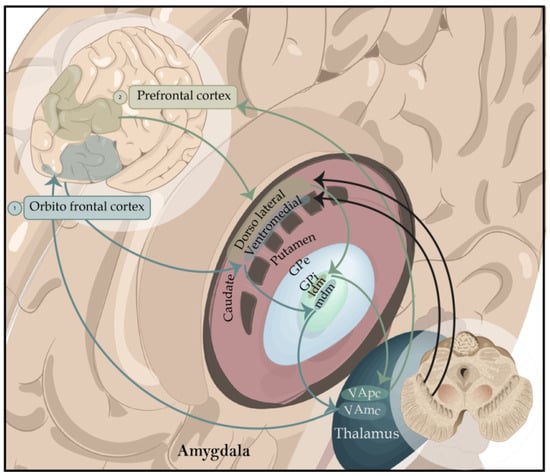

The diminution of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway is reflected in the functioning of four frontostriatal circuits connected in motor, cognitive, affective, and motivational aspects [22][26]. Two of these circuits are of particular importance in the study of cognitive aspects in PD: (1) the dorsolateral circuit, which comprises the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the striatum at the dorsolateral caudate level, the globus pallidus at the dorsomedial level, and the thalamus; and (2) the orbital circuit, which includes the orbitofrontal cortex, the striatum at the level of the ventromedial caudate, the globus pallidus at the dorsomedial level, and the thalamus [23][27]. Within each of these frontostriatal circuits, two pathways project from the striatum for different exit areas of the basal ganglia and the thalamus towards the prefrontal cortex:

-

The direct pathway (dorsal striatum/internal segment of the globus pallidus/pars reticulata of the substantia nigra/thalamus/premotor cortex/orbitofrontal cortex) exerts a facilitating action of movement.

-

The activity of the indirect pathway (dorsal striatum/external segment of the globus pallidus/internal segment of the globus pallidus/pars reticulata of the substantia nigra/thalamus/premotor cortex/orbitofrontal cortex) has a modulatory inhibition of the action of rival movements to the specific tasks the basal ganglia have chosen to do [24][28]. Therefore, the deficit of cognitive functions based on the prefrontal cortex, defined globally as an executive deficit (attention, executive roles, working memory), which characterizes many patients with PD from the early stages of the disease, does not derive so much from a direct pathology of the prefrontal cortex as from the reduction in dopaminergic stimulation at the striatal level, which prevents the normal functioning of the frontostriatal circuits. Recent neuroanatomical studies suggest that the evolutionary profile of executive deficit in PD follows the spatiotemporal progression of dopamine reduction at the striatal level concerning the different frontostriatal connections [25][29].

According to the evolutionary theory of Paul MacLean (1973) of the so-called “tripartite brain”, the structures of the brainstem (hypothalamus, thalamus, and basal nuclei), which characterize the brain of ancestral reptiles, belong to the section of the reptilian brain [26][31]. This part of the brain is responsible for the perceptual function, the sensory–motor activity that allows the discrimination and generalization of environmental objects to satisfy reproductive and metabolic needs. This is expressed thanks to the control this system exerts on the vegetative functions and the striated muscles that give rise to primordial emotions or underlying emotions. One of the critical functions of the basal ganglia is to filter the commands of voluntary movements that originate in the motor cortex. The default state of the basal nuclei consists of a signal of no movement. Nevertheless, when there is influence through the frontal cortex on the need to perform a task or several tasks, the nuclei of the base are the filters through which their circuits lead to the automatic decision-making of the motor anagrams necessary to perform only one task, dual tasks, or multiple tasks, which is a state different from its basal state of braking all types of voluntary and involuntary movement, except breathing, which has its autonomous control in the nuclei of the brain stem (bulb and bridge) [27][32]. In a certain sense, the activity of dopaminergic projections in the striatum helps to keep the “door open” to be able to execute a movement. In contrast, the loss of this activity alters the “opening of the door”, making it difficult for the individual to initiate voluntary movements [28][33] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Representation of the basal ganglia focused on cognitive functions. Ventrolateral circuit. 1. It begins in the ventrolateral frontal cortex, which is the first node of interaction with the posterior regions. It’s in charge of low-level control processes and involved in stimulus-driven recall and information retrieval from long-term memory. Lateral mediodorsal circuit. 2. It begins in the mediolateral cortex of the frontal cortex. It’s in charge of high-level executive processes and involved in the manipulation and monitoring of care and is in charge of creating organizational strategies. Abbreviations: GPe, globus pallidus pars externa; Gpi-ldm, lateral dorsomedial globus pallidus pars interna; GPi-mdm, medial dorsomedial globus pallidus pars interna; VApc, ventroanterior thalamic nucleus parvocellular part; VAmc, medialventroanterior thalamic nucleus magnocellular part.

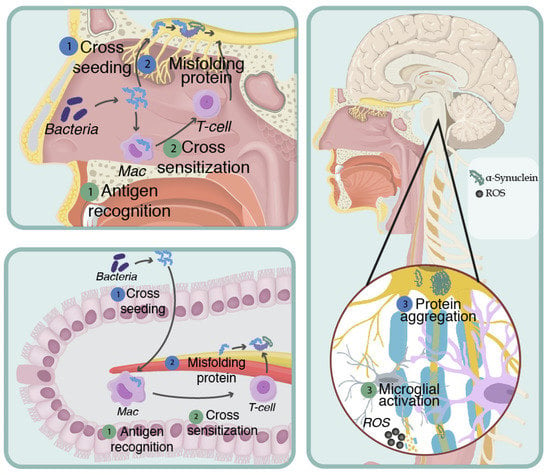

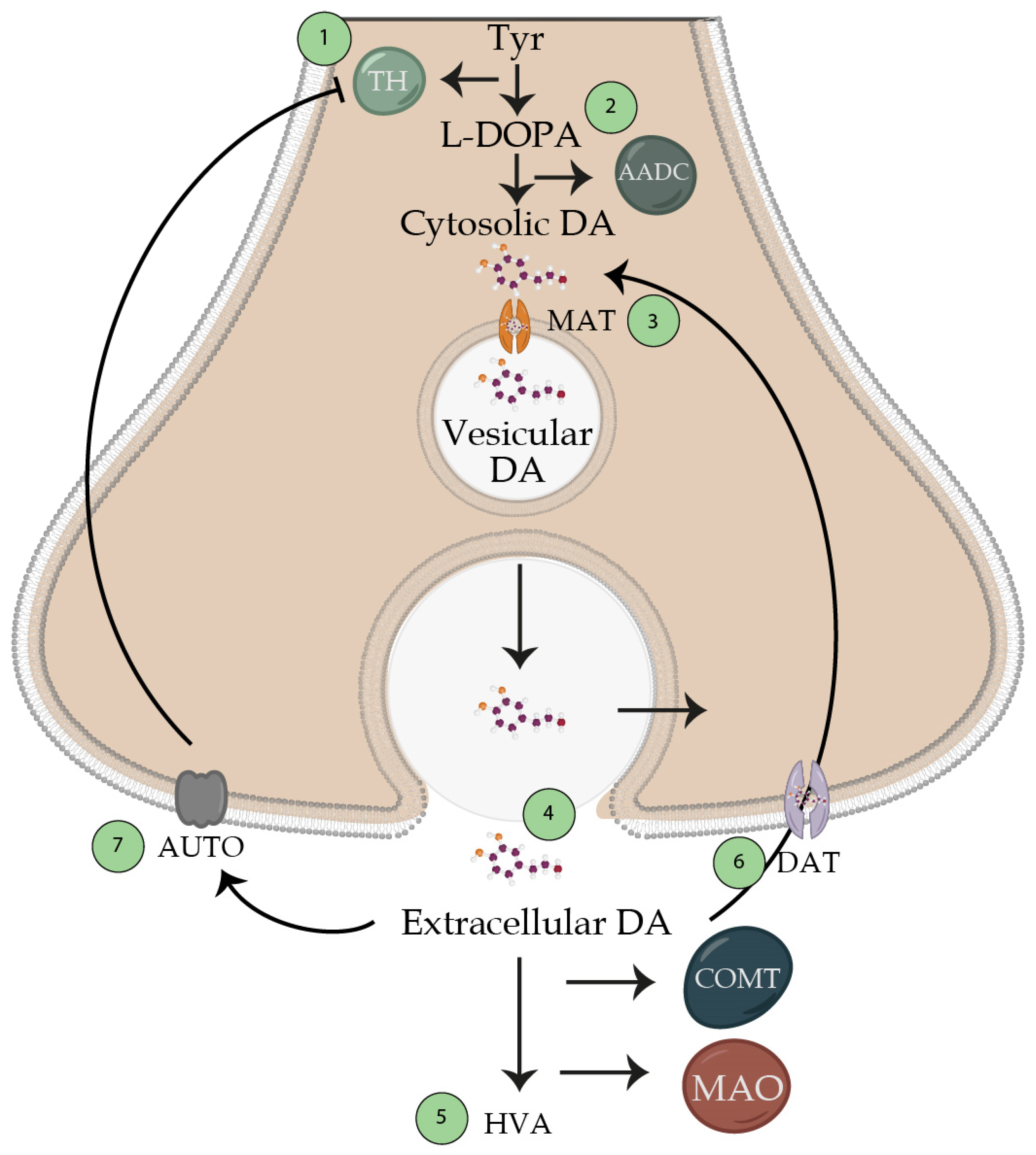

The cells of the substantia nigra synthesize the neurotransmitter dopamine, whose stages, which occur at the dopaminergic synapse, are:

- (a)

-

synthesis of dopamine from tyrosine;

- (b)

-

accumulation of dopamine by the reserve granules;

- (c)

-

dopamine release;

- (d)

-

interaction with its receptor;

- (e)

-

synaptic reactivation (reuptake) for the subsequent metabolization inactivation (Figure 4).

-

Figure 4. Dopamine synthesis. Schematic representation of the synthesis of the neurotransmitter dopamine. 1. Produced from the amino acid tyrosine, which passes through tyrosine hydroxylase, which generates L-DOPA. This enzyme is the one that limits the production of dopamine (which is inhibited by high concentrations of its substrate tyrosine). 2. Transformation of L-DOPA into dopamine by the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase enzyme, which is found in a cytosolic way and is not active for the release with the action potentials. 3. Transport of cytosolic dopamine to vesicles via the vesicular monoamine transporter enzyme. 4. The potential action releases dopamine to the synaptic cleft, so it reaches its receptor and generates its function. These nerve terminals will be found in the circuits already mentioned in the text; however, weit can find a tonic release at a frequency of 5 Hz, and another 10–15 Hz interburst release. 5. Extracellular dopamine will be metabolized by catecholamine O-methyl transferase and mono-amino oxidase towards homovalinic acid. 6. Presynaptic receptors will recapture unmetabolized dopamine for reuse. 7. Unmetabolized dopamine may bind to presynaptic receptors to block tyrosine hydroxylase. Abbreviations: Tyr, tyrosine; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; AADC, aromatic acid decarboxylase; MAT, monoamine transporter; DAT, dopamine transporter; MAO, monoamine oxidase; COMT, catecholamine O-methyl transferase.

Figure 4. Dopamine synthesis. Schematic representation of the synthesis of the neurotransmitter dopamine. 1. Produced from the amino acid tyrosine, which passes through tyrosine hydroxylase, which generates L-DOPA. This enzyme is the one that limits the production of dopamine (which is inhibited by high concentrations of its substrate tyrosine). 2. Transformation of L-DOPA into dopamine by the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase enzyme, which is found in a cytosolic way and is not active for the release with the action potentials. 3. Transport of cytosolic dopamine to vesicles via the vesicular monoamine transporter enzyme. 4. The potential action releases dopamine to the synaptic cleft, so it reaches its receptor and generates its function. These nerve terminals will be found in the circuits already mentioned in the text; however, weit can find a tonic release at a frequency of 5 Hz, and another 10–15 Hz interburst release. 5. Extracellular dopamine will be metabolized by catecholamine O-methyl transferase and mono-amino oxidase towards homovalinic acid. 6. Presynaptic receptors will recapture unmetabolized dopamine for reuse. 7. Unmetabolized dopamine may bind to presynaptic receptors to block tyrosine hydroxylase. Abbreviations: Tyr, tyrosine; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; AADC, aromatic acid decarboxylase; MAT, monoamine transporter; DAT, dopamine transporter; MAO, monoamine oxidase; COMT, catecholamine O-methyl transferase.4. Superior Functions Affected

4.1. Frontal Functions

The prefrontal cortex gives a degree of variety and complexity to the functions associated with this region and involves many processes, such as motor control, attention, working memory, and planning. The anterior part of the frontal lobes is closely linked to the limbic, motor, and sensory systems, and contributes to their regulation. The prefrontal cortex must be considered as part of an extensive attentional control network, particularly involving the parietal associative sensory regions subsequent and the mechanisms by which new behavior is automated. If the networks involved in this memory probably primarily cover those underpinning learning, a reorganization of representations is also suggested when behavior is automated. Motivational processes and reward processing thus acquire increasing importance in studies of the so-called high-level functions of the prefrontal cortex [29][46].Dopaminergic neurons are closely associated with a vast forebrain territory, including the striatum and frontal cortex. They would intervene in regulating motor, motivational, and executive functions of the cortico–striatal–thalamo–cortical circuits; the fuzzy projection architecture likely cannot support the processing and storing of detailed information.4.2. Attention

Behavioral manifestations of dysexecutive disorders include attention deficit, which manifests itself in the inability of the patient to concentrate and maintain voluntary or automatic attention, and a tendency to be quickly and tirelessly attracted to irrelevant aspects of the environment [30][50]. Specifically, patients cannot voluntarily direct attention to interesting stimuli and events and have difficulty switching attention from one stimulus to another. Patients with PD generally show poor performance both in selective attention tests, in which the relevant information for the task must be selected from among various stimuli and inhibit the interfering ones, as well as in the Stroop Test [31][51], and in divided attention tests in which the attention resources are divided among several tasks to be performed simultaneously, as in the Trail Making Test [32][33][34][39,52,53].4.3. Executive Functions

The term executive functions describes a set of psychological processes necessary to participate in adaptive and goal-oriented behaviors [35][54]. They include high-level processes such as planning, problem-solving, decision-making, cognitive flexibility, self-control, error detection, inhibition of automatic responses, and self-regulation [36][37][55,56]. All these processes allow the individual to coordinate the activities necessary to achieve a goal: formulate intentions, develop action plans, implement strategies for implementing these plans, monitor performance, and evaluate its results. Poor performance compared to control subjects is reported on executive tests [36][38][55,57].5. Psychiatric Disorders

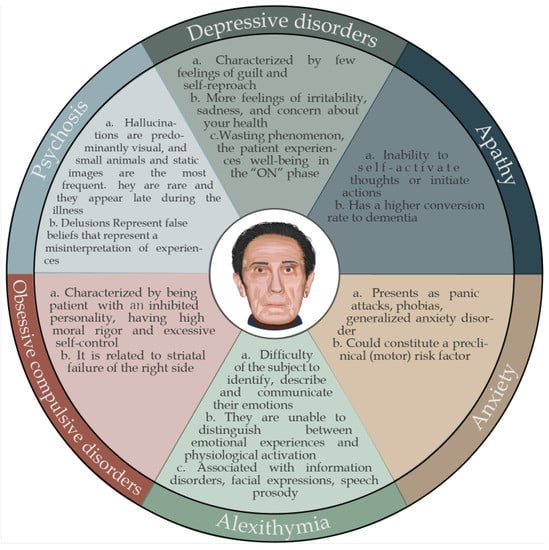

5.1. Depressive Disorders

Mood alterations in PD may precede the onset of the disease and constitute a risk factor. Recent studies report an estimated prevalence of a depressive disorder in 40–50% of parkinsonian patients. The depressive symptoms in PD are different from those of primary depression: PD patients experience fewer feelings of guilt and self-reproach and more irritability, sadness, and concern about their health status. Mood fluctuations may be accompanied by “on-–off” motor fluctuations related to the duration of the effect of dopamine therapy, with a decrease in mood during the “off” state and an improvement during the “on” state [39][64]. As the disease progresses, many patients present the phenomenon of wasting, as in a reduction in the therapeutic efficacy of every single dose, which leads to the appearance of the fluctuation mentioned above phenomena between an “on” phase, during which the patient experiences a situation of well-being with complete or sufficient autonomy, and an “off” stage, in which there is no longer a response to the drug and the symptoms of the disease reappear. Depression in PD is not reactive to the condition of the disease but has a significant biological basis resulting from damage at the level of serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic transmission [6][7].5.2. Apathy

Apathy (a loss of interest and motivation to act) is present in approximately one third of PD patients and is independent of depressive disorders. Apathy in PD is self-activated apathy, characterized by the inability to self-activate thoughts or initiate actions due to altered circuits in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the medial orbitofrontal cortex, and the gyrus cortex. Since one of the most critical functions of the basal ganglia is the self-activation of behavior guided by internal motivational impulses, apathy can be considered a pathology of the deactivation of the self-activation system that occurs after lesions of the basal ganglia. The activation of the cognitive and limbic areas of the frontal cortex in PD patients and the degree of apathy can predict the development of dementia: patients with apathy are subject to a higher rate of conversion to dementia than patients without apathy [40][67].5.3. Alexithymia

Alexithymia (the difficulty of the subject to identify, describe, and communicate emotions and to distinguish between emotional experiences and physiological activation of emotions) is of particular interest for two reasons: in the general population, alexithymia is related to the presence of mood disorders, familiar in PD. Patients with PD present difficulties in processing emotional information, such as facial expressions and speech prosody, which are reflected in less emotional reactivity to emotional stimuli [41][68]. The alexithymia construct could be a clinical index capable of detecting difficulties in handling emotional information in patients with PD.5.4. Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders are often associated with depressive disorders and may constitute a preclinical risk factor. The anxiety can present as panic attacks, phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, and somatic symptoms. As with depressive disorders, anxiety disorders can also be associated with “on–off” fluctuations related to the duration of the effect of the dopaminergic therapy, with a particular accentuation of symptoms during the “off” phases.5.5. Obsessive Compulsive Disorders

5.5. Obsessive Compulsive Disorders

The correlation between obsessive compulsive disorder and PD is due to the joint involvement of striatal structures, and the same neurotransmitters, dopamine and serotonin, are involved in obsessive compulsive and motor disorders [70]. An epidemiological study shows a higher frequency of this symptomatology than the control population, since obsessive compulsive symptoms seem to occur more frequently only in patients in advanced stages of the disease, especially patients with clinical motor onset on the left side. This phenomenon could suggest that the manifestation of obsessive compulsive symptoms is related to dysfunction of the frontostriatal circuits, especially in the right hemisphere, in line with what was found in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Some studies show that obsessive compulsive traits can manifest in the premorbid personality of PD patients: these are individuals with an inhibited nature, high moral rigor, and excessive self-control, and this personality type can induce a biochemical change in the cortex and basal ganglia over time and can be aggravated in a state of dopamine denervation by pulsatile supplementation of the same or by the addition of dopamine agonists, especially with an affinity for D3 receptors of dopamine at the mesolimbic level [71].

5.6. Psychosis

The main psychotic symptoms reported in approximately 30% of PD patients with the advanced disease include hallucinations and delusions. Psychotic symptoms may be associated directly with the disease, drug therapy, or both. Hallucinations are predominantly visual and generally appear in the second half of the disease course. Hallucinations of insects or small animals predominate, while other times, they are fleeting visions of people, adults or children, and static and silent images; however, hallucinations are rare. Visual hallucinations, which are frequently observed in patients with an intact state of consciousness, materialize as visions of people, animals, or inanimate objects; they can become illusions, that is, distorted perceptions of existing stimuli, and have threatening content, inducing feelings of fear such as Charles Bonnet syndrome, in which patients report false perception of threatening forms of objects when there is a decrease in ambient brightness [73].5.7. Acute Confusional State

The correlation between obsessive compulsive disorder and PD is due to the joint involvement of striatal structures, and the same neurotransmitters, dopamine and serotonin, are involved in obsessive compulsive and motor disorders [42]. An epidemiological study shows a higher frequency of this symptomatology than the control population, since obsessive compulsive symptoms seem to occur more frequently only in patients in advanced stages of the disease, especially patients with clinical motor onset on the left side. This phenomenon could suggest that the manifestation of obsessive compulsive symptoms is related to dysfunction of the frontostriatal circuits, especially in the right hemisphere, in line with what was found in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Some studies show that obsessive compulsive traits can manifest in the premorbid personality of PD patients: these are individuals with an inhibited nature, high moral rigor, and excessive self-control, and this personality type can induce a biochemical change in the cortex and basal ganglia over time and can be aggravated in a state of dopamine denervation by pulsatile supplementation of the same or by the addition of dopamine agonists, especially with an affinity for D3 receptors of dopamine at the mesolimbic level [43].Confusional states (delirium) are more common in elderly PD patients. An alteration in the state of consciousness is associated with cognitive (memory deficit, spatiotemporal disorientation) and perceptual (hallucinations, illusions) disorders (

5.6. Psychosis

The main psychotic symptoms reported in approximately 30% of PD patients with the advanced disease include hallucinations and delusions. Psychotic symptoms may be associated directly with the disease, drug therapy, or both. Hallucinations are predominantly visual and generally appear in the second half of the disease course. Hallucinations of insects or small animals predominate, while other times, they are fleeting visions of people, adults or children, and static and silent images; however, hallucinations are rare. Visual hallucinations, which are frequently observed in patients with an intact state of consciousness, materialize as visions of people, animals, or inanimate objects; they can become illusions, that is, distorted perceptions of existing stimuli, and have threatening content, inducing feelings of fear such as Charles Bonnet syndrome, in which patients report false perception of threatening forms of objects when there is a decrease in ambient brightness [44].5.7. Acute Confusional State

Confusional states (delirium) are more common in elderly PD patients. An alteration in the state of consciousness is associated with cognitive (memory deficit, spatiotemporal disorientation) and perceptual (hallucinations, illusions) disorders ().Figure 5 Figure 5. Summary of characteristic neuropsychiatric alterations in Parkinson’s disease.Summary of characteristic neuropsychiatric alterations in Parkinson’s disease.

Figure 5. Summary of characteristic neuropsychiatric alterations in Parkinson’s disease.Summary of characteristic neuropsychiatric alterations in Parkinson’s disease.6. Neuropsychological Alterations

6.1. Amnestics and Non-Amnestics

Impaired cognitive function in non-demented PD patients consists of a broad spectrum of clinical deficits of varying severity that affect the amnestic and non-amnestic domains. The most-compromised cognitive functions are executive functions, information processing speed, visuospatial skills, language, and working memory. Administrative functions include the ability to plan, organize, initiate, and regulate behavior. It is mainly based on the frontostriatal circuit for prefrontal regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and its connections with the basal ganglia. This frontostriatal circuit is a critical component not only in subcortical dementia in PD, but also in the mild cognitive deficit associated with PD [45].6.2. Memory Disorders

Memory disorders are often found in PD patients in the early stages of the disease [46][47]. In addition to marked alterations in working memory, PD patients show fewer deficits than Alzheimer’s disease patients in learning new information [48]. Until a few years ago, it was believed that patients with frontostriatal dysfunction, such as PD patients, performed better on recognition memory tests than free memory tests, suggesting that the storage process was intact and the retrieval process compromised [49]. Patients with PD do not have a “classic” memory profile but may have specific deficits in the individual processes that underlie the ability to memorize information; therefore, they may have different memory profiles and associations with different shapes concerning other cognitive functions. There is also the asymmetry of dopaminergic dysfunction (more significant on the side on which motor symptoms begin) about numerous cognitive functions that present asymmetric neural correlates.6. Neuropsychological Alterations

6.1. Amnestics and Non-Amnestics

Impaired cognitive function in non-demented PD patients consists of a broad spectrum of clinical deficits of varying severity that affect the amnestic and non-amnestic domains. The most-compromised cognitive functions are executive functions, information processing speed, visuospatial skills, language, and working memory. Administrative functions include the ability to plan, organize, initiate, and regulate behavior. It is mainly based on the frontostriatal circuit for prefrontal regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and its connections with the basal ganglia. This frontostriatal circuit is a critical component not only in subcortical dementia in PD, but also in the mild cognitive deficit associated with PD [75].6.2. Memory Disorders

Memory disorders are often found in PD patients in the early stages of the disease [38,77]. In addition to marked alterations in working memory, PD patients show fewer deficits than Alzheimer’s disease patients in learning new information [62]. Until a few years ago, it was believed that patients with frontostriatal dysfunction, such as PD patients, performed better on recognition memory tests than free memory tests, suggesting that the storage process was intact and the retrieval process compromised [60]. Patients with PD do not have a “classic” memory profile but may have specific deficits in the individual processes that underlie the ability to memorize information; therefore, they may have different memory profiles and associations with different shapes concerning other cognitive functions. There is also the asymmetry of dopaminergic dysfunction (more significant on the side on which motor symptoms begin) about numerous cognitive functions that present asymmetric neural correlates.Treatment with levodopa in patients in the early stages of PD facilitates cognitive flexibility (the ability to focus on multiple tasks alternately). Conversely, stopping levodopa treatment has a negative effect on cognitive flexibility but has a beneficial impact on reverse learning. This phenomenon is likely explained by the dopaminergic overdose hypothesis [50][51]. This hypothesis also suggests that the administration of levodopa replaces the decrease in dopamine in dysfunctional circuits (improving the cognitive functions connected to these circuits). Nevertheless, it causes an overdose of dopamine in mainly intact circuits (worsening the cognitive processes related to them).Treatment with levodopa in patients in the early stages of PD facilitates cognitive flexibility (the ability to focus on multiple tasks alternately). Conversely, stopping levodopa treatment has a negative effect on cognitive flexibility but has a beneficial impact on reverse learning. This phenomenon is likely explained by the dopaminergic overdose hypothesis [82,83]. This hypothesis also suggests that the administration of levodopa replaces the decrease in dopamine in dysfunctional circuits (improving the cognitive functions connected to these circuits). Nevertheless, it causes an overdose of dopamine in mainly intact circuits (worsening the cognitive processes related to them). The diminution of dopamine at the striatal level, initially in the dorsolateral frontostriatal circuit and later along the pathway, also in the orbital frontostriatal circuit, explains why the administration of levodopa is not directly correlated with improvement in cognitive performance. The clinical presentation of PD is generally asymmetric, indicating that the dopaminergic reduction is more significant in the ipsilateral hemisphere in expressing motor symptoms. This suggests that a certain dopaminergic overdose may occur not only in the frontostriatal orbital circuit but, more generally, in the cerebral hemisphere less affected by the dopaminergic reduction.6.3. Working Memory

The working memory model describes a system with limited capacity that supports human thought processes while keeping information temporarily active, providing an interface between perception, long-term memory, and action. Working memory is also deficient in PD, both spatially [52][87] and verbally [32][53][39,88]. On examining these functions through tests of verbal and visuospatial amplitude [54][89], deficits are observed, especially in conditions that require manipulation of information compared to those that require simple maintenance of the data.6.4. Decision-Making Processes

For years, neuropsychiatry and psychology have developed tasks to investigate executive functions connected to the ventromedial portion of the prefrontal cortex [35][54]. Traumatic or vascular damage in the ventromedial prefrontal site is associated with deficits in decision-making, described as “myopia or blindness for the future”; that is, the inability to evaluate and avoid the possible negative consequences of one’s actions [55][90]. Laboratory tests similar to gambling have been proposed to study the deficits in the decision-making capacity of patients with ventromedial prefrontal lesions. The Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) is the best known and used in the literature, and has been extensively used in PD patients.6.5. Language

Instrumental functions such as language and praxis are rarely altered in PD, both in patients with dementia and non-demented patients [56][91]. Patients with PD have deficits in verbal fluency [57][61], but these can be interpreted as signs of executive dysfunction rather than a primary language deficit [58][92]. The generation of words effectively requires planning skills to be intact in semantic memory. Some PD patients may have naming deficits. These linguistic comprehension deficits appear to have multiple causes: a lack of cognitive flexibility and difficulty inhibiting response appear to compromise understanding of relative sentences.6.6. Visuospatial Functions

Alterations in visuospatial functions are often reported in the literature, for example, in the Benton Orientation Judgment Test [32][39], but there is still much discussion about their genesis. Many tests are timed or involve motor dexterity factors, so even executive dysfunction can negatively affect performance on such tests (Scale Cube Drawing Test, WAIS-R) [59][95].6.7. Praxias

Apraxic disorders are poorly reported in PD [56][91]. Bilateral ideomotor apraxia is detected in 27% of PD patients compared to 75% of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy [60][99]. The degree of apraxic deficit, highlighted by the scores in the evaluation tests, is directly correlated with the degree of cognitive impairment and, in particular, executive dysfunction, confirming the crucial role of cortico-striatal circuits in the generation of apraxia. It should be noted that, in general, there is no correlation between scores on apraxia assessment tests and scores on scales that measure motor disability, such as the Unified PD Rating Scale [61][100]. This shows that ideomotor apraxia cannot be explained by the motor disability associated with PD and that these areas can be investigated independently [62][101].7. Conclusions

PD is a multisystemic condition that involves not only the nervous system but also the skin, the gastrointestinal system, and the autonomic system, among others, and in the nervous system, not only motor function is affected; on the contrary, there are non-motor symptoms that can start years before. There is evidence of non-motor symptoms that can appear during the disease, and that can sometimes be more disabling and annoying than the motor symptoms, in addition to the fact that they can aggravate the latter. Of these non-motor symptoms, neuropsychiatric problems are the ones that have a fundamental role in the disability and severity of the disease. Among the neuropsychiatric symptoms that appear even before the appearance of motor symptoms are depression that manifests itself more than as a melancholic depression, as an apathetic depression, more difficult for the patient and family to perceive, and that consists of environmental demotivation and reduction in recreational and social activities and that can occur in up to 40% of patients during the disease. On the other hand, cognitive disorders appear, sometimes from the onset of the disease, in between 20 and 35% of patients, depending on the series, and become evident in up to 40% of patients, mainly affecting care and working memory, and associated with a dysexecutive syndrome, which can generate a reduction in the patient’s quality of life and can progress to the range of major neurocognitive disorder with social dependence in up to 80% of patients between 15 and 20 years of evolution of the disease, generating severe disability, a significant reduction in the quality of life, and exhaustion of caregivers and family members. Associated with cognitive deterioration, psychiatric problems such as psychosis may also occur in 10 to 30% of patients with advanced PD due to the disease or its association with medications indicated for managing the condition. Anxiety occurs in 30% of patients during the course, and can sometimes be a fluctuating non-motor symptom associated with taking drugs and become severe.

-