Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by In Soo Kim and Version 2 by Sirius Huang.

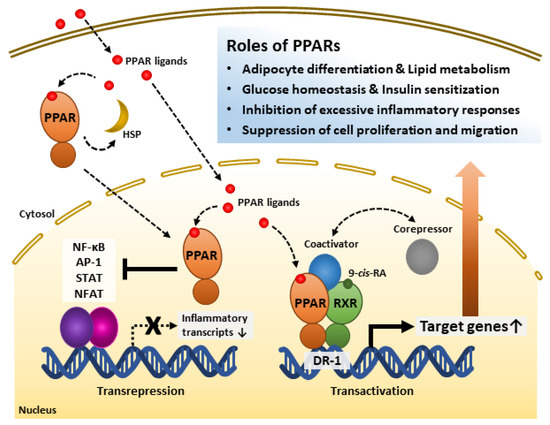

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) α, β, and γ are nuclear receptors that orchestrate the transcriptional regulation of genes involved in a variety of biological responses, such as energy metabolism and homeostasis, regulation of inflammation, cellular development, and differentiation. The many roles played by the PPAR signaling pathways indicate that PPARs may be useful targets for various human diseases.

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- infection

- bacteria

- virus

- parasite

1. Molecular Characteristics of PPARs

Peroxisomes, 0.5 μm diameter single-membrane cytoplasmic organelles, play essential roles in the oxidation of various biomolecules [1][2][17,18]. Peroxisome proliferators are multiple chemicals that increase the abundance of peroxisomes in cells [3][4][19,20]. These molecules also increase gene expression for β-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids and cytochrome P450 (CYP450) [5][6][21,22]. Given the gene transcriptional modulation of peroxisome proliferators, PPARs have been identified as nuclear receptors [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The PPAR subfamily consists of three isoforms, PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ [14][30]. The three PPARs differ in tissue-specific expression patterns and ligand-biding domains, each performing distinct functions. PPARA, encoding PPARα, is located in chromosome 22q13.31 in humans and is mainly expressed in the liver, intestine, kidney, heart, and muscle [15][16][31,32]. PPARγ has four alternative splicing forms from PPARG located in chromosome 3p25.2 and is highly expressed in adipose tissue, the spleen, and intestine [17][18][33,34]. PPARδ, encoded by PPARD, is located in chromosome 6q21.31 and presents ubiquitously [13][19][29,35]. Thus, it is essential in the study of PPARs to consider their tissue distribution and functions.

PPAR is a nuclear receptor superfamily class II member that heterodimerizes with RXR [20][21][36,37]. The PPAR structure includes the A/B, C, D, and E domains from N-terminus to C-terminus [22][38]. The N-terminal A/B domain (NTD) is a ligand-independent transactivation domain containing the activator function (AF)-1 region. The NTD is targeted for variable post-translational modifications, including SUMOylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, O-GlcNAcylation, and ubiquitination, resulting in transcriptional regulatory activities [23][39]. DNA-binding C domain (DBD) has two DNA-binding zinc finger motifs containing cysteines, which dock to PPREs. PPARs reside upstream of RXR upon the direct repeat (DR)-1 motifs, which are composed of two hexanucleotide consensus sequences with one spacing nucleotide (AGGTCA N AGGTCA) [24][40]. The hinge D region is a linker between the C and E domains, which contains a nuclear localization signal, and is the site for post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and SUMOylation [23][39]. The ligand-binding E domain (LBD) carries the hydrophobic ligand-binding pocket and the AF-2 region. The absence of agonists enables LBD to recruit co-repressors containing the CoRNR motifs [25][41]. Engaging agonists to LBD elicits conformational changes of AF-2 to facilitate interaction with LXXLL motifs of many co-activators [26][42]. Like other nuclear receptor superfamily class II members, such as thyroid hormone receptor (TR), retinoic acid receptor (RAR), and vitamin D receptor (VDR), PPARs function as heterodimers with RXR through LBD [27][28][6,43]. LBD is also targeted for SUMOylation and ubiquitination [23][39]. Advancement of research on the PPAR structure helps thoroughly dissect the roles of PPARs. The roles of specific PPAR subtypes will be discussed in the following subsections.

1.1. Roles of PPARα

PPARα is predominantly expressed in the liver but is also found in other tissues, including the heart, muscle, and kidney [16][29][4,32]. PPARα regulates the expression of genes involved in metabolism and inflammation. Activation of PPARα leads to the upregulation of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and the downregulation of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis [30][8]. PPARα also modulates other genes, including genes involved in the transport and uptake of fatty acids and the synthesis and secretion of lipoproteins [29][30][4,8]. In addition, activation of PPARα has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce oxidative stress, and reduce inflammation in preclinical studies [30][31][32][7,8,44]. PPARα activation has been shown to modify the expression of immune response genes, including those encoding cytokines and chemokines, which are signaling molecules that regulate the immune response [32][33][44,45]. PPARα activation has also been demonstrated to reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-6 [34][35][46,47]. PPARα has been shown to interfere with the DNA binding of both AP-1 and NF-κB [33][34][36][45,46,48]. Thus, the roles of PPARα in infectious diseases should be studied in wide ranging aspects, including metabolism and inflammation.

In the context of infection, PPARα has been shown to play an essential role in the hepatic metabolic response to infection. During an infectious challenge, the liver coordinates several metabolic changes to support the host defense response, including the mobilization of energy stores, production of acute-phase proteins, and synthesis of new metabolites. Activation of PPARα in the liver leads to the upregulation of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis with fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) production [37][49]. FGF21 is a hormone produced by the liver that has been shown to promote ketogenesis and reduce glucose utilization [38][39][50,51]. The ketogenesis regulation of PPARα with FGF21 is essential for reacting to microbial or viral sepsis [40][41][42][52,53,54]. In conclusion, the hepatic PPARα metabolic response to infection is crucial to the host defense response.

1.2. Roles of PPARβ/δ

PPARβ is expressed in diverse tissues, including adipose tissue, muscle, and the liver [13][43][29,55], and is activated by multiple ligands, such as fatty acids and their derivatives [31][7]. PPARβ is involved in regulating lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis, as well as controlling inflammation and immune function [44][56]. PPARβ activation has been demonstrated to have pro- and anti-inflammatory effects based on the situation [44][56]. The role of PPARβ in tumorigenesis is debatable. PPARβ activation has been found in some cases to have anti-tumorigenic effects, such as causing apoptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation [45][46][57,58]. In other cases, however, activation of PPARβ has been shown to promote tumorigenesis by enhancing cell survival, promoting angiogenesis, and reducing cellular differentiation [47][48][49][50][59,60,61,62]. Overall, the role of PPARβ activation in cancer is not entirely known and is complex. Similarly, the function of PPARβ in infection is not well understood. Additional research is required to comprehend the function of PPARβ in the context of immunology against cancers and infectious diseases.

1.3. Roles of PPARγ

PPARγ is expressed in a variety of tissues, including adipose tissue, muscle, and the liver [17][18][43][33,34,55], and is activated by diverse ligands, including fatty acids and their derivatives, as well as synthetic chemicals known as thiazolidinediones [29][31][4,7]. PPARγ is responsible for regulating lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis, and inflammation [51][52][63,64]. Numerous inflammatory mediators and cytokines are inhibited by PPARγ ligands in various cell types, including monocytes/macrophages, epithelial cells, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes. In addition, PPARγ diminishes the activities of transcription factors AP-1, STAT, NF-κB, and NFAT to adversely regulate inflammatory gene expression [53][54][55][65,66,67]. As a result, PPARγ has been demonstrated to have a protective function against infections by modulating the immune response and lowering inflammation. However, other researchers have hypothesized that PPARγ activation may impair the function of immune cells, such as macrophages, and contribute to the development of infections. Therefore, the role of PPARγ in disease is complex and context-dependent, and more research is needed to fully understand the molecular mechanisms by which PPARγ regulates the host response to infection.

2. Regulatory Mechanisms of PPARs

The PPAR ligand-binding pocket is large and capable of engaging diverse ligands [56][57][68,69]. Endogenous ligands vary depending on the PPAR isoform, including n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid for all PPARs, leukotriene B4 for PPARα, carbaprostacyclin for PPARδ, and prostaglandin J2 for PPARγ [58][70]. Representative synthetic agonists include fibrates (PPARα agonists) and thiazolidinediones (PPARγ agonists) [31][7]. Fibrates, such as fenofibrate, clofibrate, and gemfibrozil, are widely used for treating dyslipidemia. Thiazolidinediones, such as rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, and lobeglitazone, improve insulin resistance [31][7]. Most clinical studies on PPAR actions in infectious diseases have been conducted retrospectively, and no clinical studies currently in progress are listed in ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 13 February 2023)). Since widely used PPAR agonists exist, clinical research can be conducted through a deeper understanding of PPAR roles in infectious diseases.

PPAR-RXR heterodimerization occurs ligand-independently [27][6]. The heterodimer appears to exert transcriptional regulation both ligand-dependently and -independently [31][7]. Although LBD may interact with either co-repressor or co-activator in the state of not binding with an agonist, binding to a ligand elicits stabilized co-activator-LBD interaction, thus increasing transactivation [31][59][7,71]. Further, recent studies have shown that PPARs inhibit other transcription factors, such as NF-κB, activator protein-1 (AP-1), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) [32][53][54][55][44,65,66,67]. Recent studies revealed the possibility of forming a protein chaperone complex with PPAR-associated proteins, such as heat shock proteins (HSPs). Similar to interactions between other type I intracellular receptors and heat shock proteins, HSP90 repressed PPARα and PPARβ activities but not that of PPARγ [60][72]. Instead, HSP90 was required for PPARγ signaling in the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease mouse model [61][73]. Thus, it is necessary to study the various modes of PPAR actions. The intracellular regulatory mechanisms of PPARs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and their regulatory mechanisms. PPAR ligands bind to the PPAR ligand-binding domain and activate receptors. PPARs interact with heat shock protein (HSP) in the cytosol. PPARs inhibit inflammation-related gene transcription by interfering with transcription factors such as NF-κB, AP-1, STAT, and NFAT. PPARs form heterodimers with Retinoid X receptor (RXR), a receptor of 9-cis-retinoic acid (9-cis-RA), and bind to direct repeat 1 (DR-1), a peroxisome-proliferator-responsive element. The PPAR-RXR heterodimer complex and co-repressors represses target gene transcription. However, the complex with co-activators promotes target gene transcription. Through these mechanisms, PPARs play significant roles in energy metabolism, inflammatory modulation, and the cell cycle. AP-1, Activator protein 1; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NFAT, Nuclear factor of activated T cells; STAT, Signal transducer and activator of transcription.