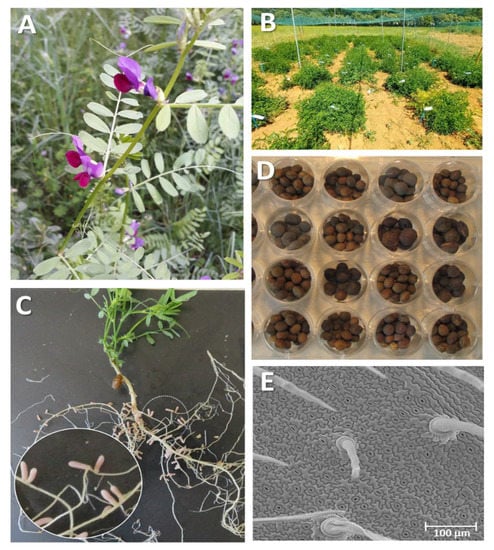

Common vetch (Vicia sativa L.) is a grain legume used in animal feed. It is rich in protein, fatty acid and minerals content, therefore is a very suitable component for feed enrichment. Furthermore, important pharmacological properties in humans have been described. Like other legumes, common vetch has the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, an important characteristic in sustainable agricultural systems. These characteristics enhance the usage of vetch as a cover crop and its use in intercropping systems. In addition, several recent studies have highlighted the potential of vetch in the phytoremediation of polluted soils. These features make common vetch an appropriate crop to address for various potential improvements. Comparative analyzes have allowed the identification of varieties with different flowering time, shattering resistance, yield, nutrient content and composition, drought response, rhizobacteria associations, nitrogen fixation capacity, and other agronomically relevant traits. The status and evolution of vetch cultivation worldwide from a historical, economic, and environmental perspective have been reviewed.

- Vicia sativa

- common vetch

- breeding

1. Introduction

2. Taxonomy

The botanical tribe Viceae, from the subfamily Papilioboideae, of the family Fabaceae, includes some genus of agricultural interest such as Lens, Cicer, Pisum, Lathyrus, and Vicia [5]. The genus Vicia, whose center of origin and diversification has been placed in the Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian regions [6], includes a number of species ranged between 150 [7] and 210 [8], from which 34 are cultivated. The genus is, nowadays, distributed in temperate regions of the northern hemisphere in Asia, Europe, and North America, and also in the non-tropical region South America [9]. This genus has an enormous phenotypic variation [10]; in fact, there has been a big number of taxonomic revisions made over the genus, more than 20 since the original classification presented by Linneo (1735–1770) in the 18th century, following for those of Jaaska and other authors [9][11][12][13][14][15][9,11,12,13,14,15]. In a focus on V. sativa section Vicia, which includes the most important agricultural species, one of the last classifications was proposed by Van der Wouw et al. [16] after several studies focus on Vicia L. series Vicia, who presented a classification of this series in four species: V. babazitae Ten&Guss., V. incisa M.Bieb., V. pyrenaica Pourr., and V. sativa, which includes six subspecies: nigra (L.) Ehrh., segetalis (Thuill) Čelak., amphicarpa L.Batt, macrocarpa (Moris) Arcang., cordata (Wulfen ex Hoppe) Batt., and sativa. This group of forms is named the V. sativa aggregate. Commercially vetch includes, in addition to V. sativa, V. villosa Roth. (winter vetch, hairy vetch) and other species of similar local importance such as V. pannonica L. in Turkey, V. pannonica, V. ervilia L. and V. articulata Hormen in Spain, and V. benghalensis L. in Australia; the same term, vetch, has been used for different species such as Lathyrus sativus L. and other Lathyrus species in Africa [17].3. A Historical Crop

The common vetch, similar to other species of the Fabaceae family, has been cultivated together with cereals since the beginning of agriculture. Archaeological evidences indicate the Mediterranean Basis as the center of origin and primary diversification of this species [18][19][18,19]. Some authors indicate that the first archaeological references to vetch seeds date back to the Neolithic Periodic and the Bronze Age. This point is not clearly established because these seeds could also belong to wild species, associated with the crops. Additionally, others authors such as Zohary [20][21] disagree with this approach, dating the use of vetch into the agricultural systems in the Roman Empire, at a time when the use of vetch as a fodder species as already been reported, together with others species such as alfalfa and lupin or fenugreek, also associated with cereals and others grain legumes [21][22]. Columela, an ancient Roman scientist and writer who lived in the first century B.C. cited the use of vetch for poultry (hens and pigeons) feeding and as a fodder and green manure, together with other legumes such as alfalfa and fenugreek [22][23]. In the same time period, Plinius The Elder (First century B.C.) said that their use would improve soil fertility, giving indications about the sowing times in the function to the final use, including the use as fallow [23][24]. This author mentioned that vetch was the best feed for the bullocks. In the 4th century, Paladio described the use of a mixture of lupin and vetch as a soil improver when cutting in green, and they also made mention of the differences in the sowing date of the function of the final use. Isidore of Seville, who lived between the 6th–7th century, highlighted the scarce production of seed of vetch compared with other legumes [24][25]. In the Middle Age (11th and 12th century), vetch was a minority crop in Europe [25][26], even if the Andalusian author Abü l-Jayr indicated names such as Umda or Amank to identify different forms of vetches [26][27]. In the 16th century, Juan de Járava wrote that this species could be found among cereals and that it could be eaten as lentils, although it did not taste good [27][28]. In this century, vetch traveled to the New World, adapting perfectly to the local conditions of America, to the point that some escapees from cultivated vetches came to grow wild in the new environmental conditions [25][26]. Thus, in the 19th century, vetch was introduced to Argentina by Italian immigrants (settlers) establishing it as a well-known fodder [28][29]. To conclude this historical revision, a book from the 18th century used several names for cultivated and wild vetches and mentioned that they were a well-known crop in Europe, and that they could have reached Spain from the east by crossing France. Here, also, its uses as grain, green manure, and as a flour component to make bread in times of scarcity are mentioned [29][30].4. Worldwide Vetch Cultivation

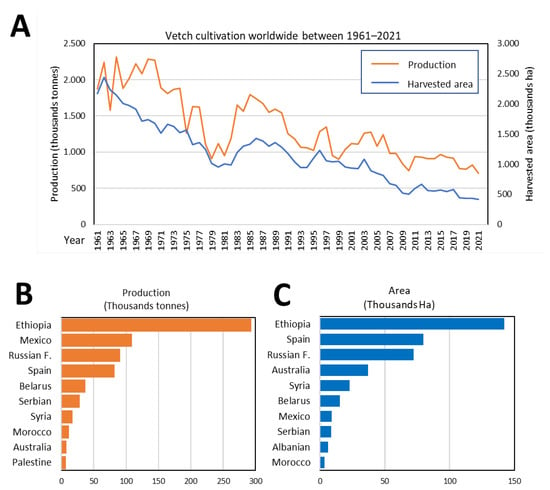

Due to its economic and ecological advantages (Figure 1), vetch is now widespread throughout many parts of the world. Figure 12A shows, based on data by FAOSTAT and the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food [30][31], the surface and production of this crop from 1961 to 2021 are shown in Figure 12A. In the agricultural season of 2020–2021, the main producers were Ethiopia, the Russian Federation, Spain, Mexico, and Australia (Figure 12B,C).

5. Nutritional and Pharmacological Properties

The nutritional value of the common vetch as a livestock feedstuff has been analyzed in different studies that have recently been reviewed [2][31][2,32]. The main conclusions of different works agree with the potential of common vetch grain, despite of the well-known deficit in sulfur amino acids (methionine and cysteine), as a rich source of proteins, minerals, and other nutrients, while being cheaper than other alternatives. The average crude protein values range from 21 to 39% (dry matter) and crude fat ranges from 9% to 38%, with high levels of palmitic and linoleic acids. The main essential and non-essential amino acids are leucine and glutamic acid, respectively. The seeds have high caloric content and are highly digestible [2]. These characteristics make vetch a potential nutrient-rich resource to be incorporated into animal diets and are very suitable to replace soy or a large proportion of cereals in certain feeds, maintaining their energy content. The nutritional content of the vetch seeds has been analyzed, and great differences in protein content, fatty acid composition, and mineral composition, including iron, were observed between accessions from different geographical origins. Although these studies have been carried out on a small scale, these data support the use of the variability of genetic resources from the gene banks of V. sativa for breeding purposes [32][33]. Remarkably, the large variation in crude protein and mineral content between different cultivars is much greater even than that due to climatic conditions [2][33][34][2,34,35]. This fact must be considered when selecting varieties with better nutritional conditions. The medical uses of V. sativa have been also explored [35][36]. The seed flour and plant extract are traditionally used as an anti-poison and antiseptic [36][37][37,38], as an anti-asthmatic and respiratory stimulant in bronchitis [38][39], and as rheumatism treatment and an antipyretic [39][40]. Anti-acne [40][41] and antibacterial activity has been also validated [41][42]. However, most of the phytopharmacological mechanisms of action remain to be unraveled. As described in other grain legumes, common vetch seeds contain a variety of antinutritional factors (ANFs), such as vicine, convicine, tannins, phenolic compounds, trypsin inhibitors, and cyano-alanines. Although some of these elements, such as polyphenols, have been studied as a source of antioxidants [42][43], these ANFs have partially limited the use of the seeds in food and/or feedstuffs, especially in the diets of monogastric animals [43][44]. However, the inclusion of a high proportion of common vetch seeds in the diet of ruminants does not produce relevant negative effects on their health [44][45][46][47][48][49][45,46,47,48,49,50]. The levels of anti-nutritional factors such as tannins, trypsin inhibitors, and hydrogen cyanide nutrients show huge variations between different accessions conserved in gene banks [32][33]. These variations have permitted the selection of low vicianine levels in common vetch accessions and have allowed the production of cultivars such as Blanchefluer without vicianine [50][51][51,52], extensively growing in Australia as a substitute for red lentils, although its consumption in humans is residual [17]. Last year, the molecular bases that regulate the hydrogen cyanide (HCN) synthesis from these cyanogenic glycosides have been unraveled in common vetch. Transcriptomic assays at different seed developmental stages enlighten important information about the regulatory network of this pathway. Eighteen key regulatory genes that are involved in HCN biosynthesis have been identified. These genes would be crucial as molecular markers for the selection and breeding of low HCN levelled vetch germplasm [52][53]. In any case, and especially for non-ruminant diets, it seems that these ANFs present in common vetch seeds need to be reduced or partially inactivated by adequate grain processing methods. A practical approach would be the selective breeding of varieties with a lower content of these antinutrients, but also the processing by soaking, chemical treatment, dehulling heat treatment, or germination. These treatments not only reduce the ANF content, but also improve the digestibility, palatability, and availability of the nutrients [34][53][54][35,54,55].6. Environmental Benefits

The multiple benefits of common vetch for the farm as a versatile crop have been reviewed [2][31][2,32]. Plants need relatively large amounts of nitrogen for proper growth and development. The largest input of N into the terrestrial environment occurs through the process of biological nitrogen fixation (BNF). Therefore, BNF has great agricultural and ecological relevance, since N is often a limiting nutrient in many ecosystems [55][56]. The reduction of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers through the use of legumes not only has a decrease in environmental impact but also an economic one, due to the prices of these fertilizers, whose synthesis involves a large energy cost [56][57]. Rhizobia from legume-symbiotic systems make use of its nitrogenase enzyme to catalyze the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3), which is a plant assimilable nitrogenous compound. This process utilizes energy produced by the legume photosynthesis and takes place in the symbiotic nodules of the legume roots. As other species of the Vicia genus, common vetch forms indeterminate-type root nodules through symbiosis with rhizobia to promote nitrogen fixation (Figure 23C). The interaction between the bacteria and host legume is so intricate that many rhizobial species nodulate in a host-specific manner despite the fact that the same symbiotic bacteria can infect different species, and even different genera, of legume. Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae (Rlv) is the most common symbiont of V. sativa in which effective nitrogen fixation has been validated [55][56]. Furthermore, different strains of the Mesorhizobium and Bradyrhizobium genus have been isolated from V. sativa nodules, although there are no data about their ability to fix nitrogen [57][58]. Specific rhizobial nodule establishment in the plant host not only depends on the strain abundance in soil but also their nodulation competitiveness. R. leguminosarum biovar viciae establishes symbiosis with several legume genera, and genomics studies reveal plant preferences between specific rhizobial genotypes and the host V. sativa [58][59]. The complexity of these symbiotic associations and their specificity have been extensively addressed. These interactions present differences between V. sativa cultivars and wild relatives and are also affected by environmental conditions [57][58]. Moreover, the analysis of symbiotic genes of R. leguminosarum isolated from V. sativa from different geographical locations reveals a common phylogenetic origin, suggesting a close coevolution among symbiotic genes and legume host in this Rhizobium-Vicia symbiosis [59][60]. Symbiosis within V. sativa and Rlv has also been chosen as a model system to analyze different bacterial compounds, mainly oligosaccharides, and the plant-produced nod gene inducers (NodD protein activating compounds) involved in the establishment of the effective symbiosis with its host plant and the requirements for the host-plant specificity [60][61][62][63][61,62,63,64]. The bacterial nodulation genes (nod) are activated by flavonoids excreted by the common vetch roots [64][65], and, subsequently, the plant responds with the development of the root nodule [65][66]. Several physiological, biochemical, and transcriptomic analyses support an increase in drought tolerance in nodulated vetch plants compared to non-nodulated ones. Transcriptomic analysis has helped to discover specific drought pathways that are specifically activated in nodulated V. sativa plants, improving the understanding of the impact of the symbiosis-associated genetic pathways on the plant abiotic stress response [66][67].

| Pollutant | Developed Assay | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cd | Cd tolerance. Oxidative damage accumulation. | [95][96] |

| Cd and Zn | Zn and Cd accumulation in different tissues | [94][95] |

| Zn | Zn tolerance | [97][98] |

| Cu | Cu tolerance | [90][91][91,92] |

| Salt | Tolerance to salt. Na and K accumulation | [83][84] |

| Hg | Hg accumulation in different tissues | [93][99][94,100] |

| Ni | Ni accumulation. Oxidative damage accumulation. | [96][97] |

| Sulfosulfuron herbicide | Tolerance to sulfosulfuron | [84][85] |

| Diesel fuel | Tolerance to diesel | [89][90] |

| Phenol derivatives | Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) dissipation | [86][87] |

| Phenolics | Tolerance to phenolics. Effects on biomass, nodulation and nitrogen fixation activity | [88][89] |

| Mepiquat | Tolerance to mepiquat | [87][88] |