Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Iwona Olejniczak and Version 2 by Camila Xu.

The circadian clock is a prominent regulator of physiology. Most lifeforms on earth use endogenous, so-called circadian clocks to adapt to 24-h cycles in environmental demands driven by the planet’s rotation around its axis. Interactions with the environment change over the course of a lifetime, and so does regulation of the circadian clock system.

- circadian clock

- prenatal development

- infancy

- childhood

1. Introduction

An organism needs to interact with its surroundings in search of nutrition, to protect itself from predation, and to seek mates. In addition to reacting to environmental changes, anticipation of such conveys survival benefits. Most lifeforms on earth are subjected to a 24-h day-night cycle driven by the planet’s rotation around its axis. An intrinsic biological timing tool, called the circadian clock, keeps track of this rhythm. Mechanistically, the circadian clock is generated by a transcriptional–translational feedback loop. The exact players vary between species, but in mammals the core clock loop consists of the brain and muscle ARNT-like 1—circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (BMAL1-CLOCK) dimer as positive regulator and Period (PER1-3) and Cryptochrome (CRY1/2) complexes as negative regulators. Additional proteins such as Reverse erythro-blastoma (REV-ERBα/β), RAR-related orphan receptor (RORα-γ), D-box binding PAR bZIP transcription factor (DBP) and Nuclear factor, interleukin 3 regulated (NFIL3) form stabilizing loops [1]. Together with inputs through post-translational modifications of these clock proteins involving Casein kinase 1 and Sirtuin 1 (CK1δ/ε and SIRT1, respectively, refs. [2][3][2,3]) they create a ~24-h oscillation. The main circadian pacemaker is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, but functional clocks are expressed in almost all tissues and cells [4][5][4,5]. While principally autonomous, this clock network receives signals from the environment that realign its oscillations with the external light-dark cycle on a daily basis in a process called entrainment. Light is the most potent entrainment signal (or zeitgeber, reviewed in [6][7][6,7]), but others—e.g., food intake, exercise—also synchronize the clock [8][9][10][8,9,10].

2. Prenatal and Infancy

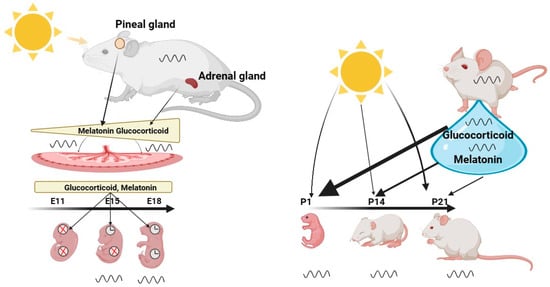

Prenatal period—A first description of circadian clocks during development was provided by Reppert and Schwartz in 1983 [11][14], who elucidated daily changes in glucose utilization in mouse embryos three days before gestation. These glucose rhythms reflected the maternal phase. Subsequent studies on mothers with Bmal1 deficiency and SCN lesions confirmed this finding [11][12][13][14,15,16]. Intriguingly, studies on female mice with double clock gene mutations showed that the fetal clock rhythm remains unchanged [14][17]. This indicates that the pups are capable of developing autonomous circadian rhythms even without central and maternal clocks and the maternal clock helps to synchronize the fetal clock during gestation. Hence, the development of the embryonal clock relies strongly on the maternal circadian system to set the environmental context and relay time of day information [15][16][18,19]. From the start of fertilization, the embryo relies on maternal nutrition and communication via several signals, including hormones, to be best prepared for life outside of the utero. To meet the required conditions for the developing fetus, changes in maternal physiology during pregnancy are necessary. These changes involve release rhythms and concentrations of hormones, e.g., glucocorticoids (GCs) and melatonin, which are conveyed via and, in part, controlled by the placenta (Figure 1) (the interface between fetal and maternal circulatory systems) [15][17][18][18,20,21].

Figure 1. The Role of the Maternal Clock in Synchronizing the Clock of the Embryo and Infant. Maternal signals, such as melatonin and glucocorticoids, gradually increase during the gestation period and synchronize the circadian clock of the embryo. These hormones are transmitted through and controlled by the placenta, which serves as the interface between the fetal and maternal circulatory systems. Their function is to adapt the developing embryo to the external environment, ensuring optimal preparation for life outside the womb. Central and peripheral clocks exhibit different developmental states, with the central clock exhibiting rhythmicity as early as E13, while the peripheral clocks only become rhythmic at developmental age of E18.After birth, the infant is no longer directly synchronized by the maternal suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), but relies largely on its own independent clock, which can be directly synchronized by light. However, breast milk, illustrated by a blue drop, contains hormones such as melatonin and glucocorticoids that can modulate the synchronization of the infant’s clock, particularly in the first few days after birth. Once the infant’s retina is fully developed at P13, light becomes a stronger synchronizer than maternal milk. Created with BioRender.com.

3. Childhood and Adolescence

Childhood—One of the most prominent physiological outputs of the circadian clock is the sleep/wake rhythm. This has been intensively studied in humans and rodents alike. Sleep is regulated by two processes, the circadian process (process C), and the homeostatic process (sleep pressure or process S). The circadian component of sleep is SCN dependent but also relies on the hormone melatonin, produced in the pineal gland during the dark period. Dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO), which is the start time of melatonin production when decoupled from external light cues, is considered the gold standard for assessing the circadian pacemaker phase in humans [113][116]. Another tool used by chronobiologists to assess the general clock phase is the Munich chronotype questionnaire [114][117]. This estimates clock phase by tracking voluntary sleep schedules. Both tools have been used in young children and have been shown to be a reliable measure of circadian rhythms. Young children and toddles differ from adults, as they are predominantly morning chronotypes (i.e., showing earlier bedtimes) [115][118] with earlier DLMO [116][119]. They also tend to follow a biphasic sleep pattern, the disappearance of which is one of the milestones of early childhood [117][120]. Unsurprisingly, regular napping leads to kids falling asleep approx. 1 h later at night, with higher sleep latency and shorter sleep duration when compared to non-napping toddlers [118][121]. While the children transition out of the biphasic sleep pattern, they may be experiencing sleep loss, as exemplified by an increased slow-wave activity of toddlers deprived of a nap [117][120]. Children (and teenagers, which will be discussed below) are often forced to function according to their parents’ schedule, or that of their preschool. Misalignment of one’s intrinsic clock and such social schedules—which is usually followed by elongated and shifted sleep schedules during free days, resembling short transcontinental trips on sleep logs—is termed social jetlag (SJL). In fact, kids attending preschool experience higher rates of social jetlag than their home-staying peers (differences of 26.3 vs. 17.6 min in sleep phase between weekdays and weekends) with a quarter of kids’ SJL being greater than 30 min [119][122]. While larger SJL correlates with health problems [120][121][123,124], such a connection has not yet been definitively described for young kids. For example, SJL in children has no significant negative effects on temperament [119][122]. However, young children entrain to light with high individual sensitivity [122][125] and, similarly to adults, will phase advance their rhythm when in more natural environments (camping, low light pollution, ref. [123][126]). This light entrainment may have adverse effects when mistimed, as children sleeping near a screen tend to get around 20 min less sleep [124][127]. Adolescence—While alterations in sleep patterns of young children may be a cause for concern for their parents, the weekly shifts in sleep patterns seen in many teenagers are significantly worse. As many as 45% of US adolescents may not be getting adequate sleep [125][128] and as many as 16% may suffer from delayed sleep phase disorder characterized by increased daytime sleepiness and inability to sleep at normal times [126][127][129,130]. This is mostly caused by a rapid phase-delay in chronotype which accompanies the onset of puberty and reaches its peak at around 20 years of age [128][129][131,132]. While the end of puberty is marked by the cessation of bone growth, the end of adolescence, as proposed by Roenneberg et al. in 2004, could be defined as the point of one’s latest chronotype. Its timing also shows a sex difference, with girls reaching it approx. 1.5 years earlier than boys [129][132], in line with the earlier onset and completion of puberty in females. Considering that these delays in phase correlate with secondary sex development [128][129][130][131,132,133] and both sleep and the circadian clock are modulated by steroids [131][132][133][134][134,135,136,137], one could infer a cause–effect relationship. Physiologically, the shift to later chronotypes seems to be caused by a combination of slower sleep pressure build-up and a circadian phase delay [125][128]. Indeed, a study comparing pre-, early- and post-pubertal children shows that the sleep pressure dissipation rate (measured as the decline in the 2-Hz electroencephalography power band) does not differ, while the build-up of sleep pressure is slower in the older group [135][138]. This is likely compounded by environmental factors such as limited exposure to light during schooldays coupled with increased exposure to light-emitting electronic devices in the evening [136][137][139,140]. On a molecular lever, the physiological phase shift could be driven by chromatin modifications, as it was observed that later sleep timing correlates with methylation levels of circadian genes [138][141]. While this phenomenon was mostly studied in humans, a few animal studies show that it may similarly apply to other mammalian species. A similar shift of 1 to 4 h in activity rhythms during puberty was observed in macaques, degus, rats, mice and in fat sand rats [125][128]. Juvenile mice also show differences in their entrainment capacities [139][142]. Late chronotypes, which teenagers predominantly are, tend to sleep less on average, experience greater SJL and compensate for lost sleep on weekends [140][143]. This may affect their physical and mental health. As a consequence, researchers have recommended that school start times should be delayed to fit the natural rhythm of adolescents [141][142][144,145]. A pilot study which shifted the school start time from 8:50 AM to 10:00 AM showed a 12% improvement in academic progress and 50% drop in absences due to illness [143][146]. Additionally, to mitigate the harmful effects of blue light exposure, a week of blue light blocking glasses was shown to attenuate LED-induced melatonin suppression and subjective alertness before bedtime [144][147].4. Menopause

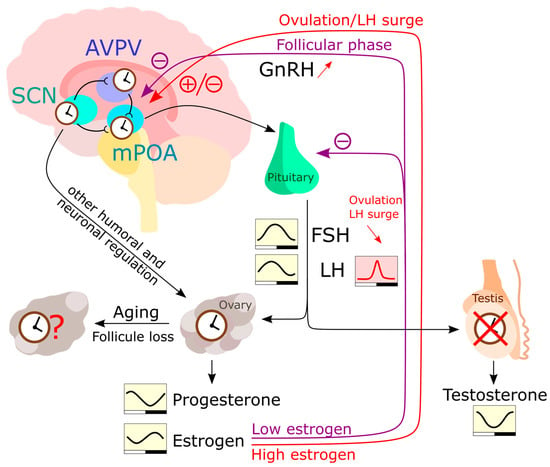

Reproduction in mammals only lasts for a limited time [145][148]. This applies to females and, to a smaller extent, to males. Both sexes, however, experience physiological changes during the aging process related to changes in sex hormone levels [146][149]. The onset of menopause is often described as the end of a woman’s “biological clock” [147][148][150,151]. When the ovaries start running out of egg follicles that release estrogen, they also become less responsive to other hormones that stimulate ovulation. As a result, the ability of females in terms of reproduction rapidly drops to zero, whereas andropause in men is characterized by a rather gradual reduction in testosterone levels over decades [149][152]. This testosterone level reduction, however, has only little effect on the viability of sperm cells and, thus, the principal ability to reproduce [150][151][152][153,154,155]. Clock of the reproductive system—The discovery of the ovarian clock [153][154][156,157] considerably changed the perspective on reproduction in women. The ovarian clock is controlled by neuroendocrine signals from the SCN [155][158]. A substantial body of evidence from human and mouse studies shows that the circadian clock plays a crucial role in the physiological processes of the reproductive system, such as ovulation and hormone secretion. Deficiencies in the circadian clock through clock gene mutations can lead to impaired reproductive success [156][159]. For example, female mice with Bmal1 deficiency or double clock mutations in Per and Cry exhibit disrupted mating behavior and infertility [157][158][159][160][161][162][163][164][160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167]. Single clock gene mutations in Per1 and Per2 lead to reduced ovarian function [157][165][166][160,168,169]. Conversely, other studies in Bmal1 knockout and Clock mutant mice show that a deficiency in clock genes weakens the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge, but ovulation is unaffected [68][161][167][168][71,164,170,171]. Thus, the circadian rhythm appears to play a crucial role in determining the timing of the LH surge, but it is not necessary for spontaneous ovulation. The local clock in the ovaries, however, has a significant impact on the timing of the ovulatory response to LH [169][172]. This suggests that the ovarian clock may control LH receptor signaling and ultimately influence the timing of ovulation. HPG axis—In female rodents during the ovulatory cycle, sex steroid secretion is controlled similarly to that in males via the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad (HPG) axis (Figure 2). It initiates from a neuroendocrine cascade, e.g., gonad releasing hormone (GnRH) in the medial preoptic area (mPOA), kisspeptin neurons in the anterior ventral paraventricular nucleus (AVPV), and arginine vasopressin (AVP) neurons in the SCN. This dictates the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) in the pituitary gland [155][170][158,173] (Figure 2). Both hormones act on gonads and induce gametogenesis and sex hormone production. During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, FSH stimulates the maturation of ovarian follicles and the secretion of estradiol. When estrogen levels consistently peak for 48 h in a human, the secretion of FSH is suppressed, leading to a surge in GnRH from the hypothalamus. This GnRH surge stimulates the release of gonadotropic hormones, including a surge in LH. The combination of the FSH peak and LH surge triggers ovulation. Following ovulation, FSH levels remain low, preventing the growth of additional follicles [171][174]. Additionally, they modulate the clock gene rhythm in the ovarian tissue [172][173][175,176]. Aging female SCN—The activity of the HPG axis is regulated by three crucial brain nuclei, i.e., the mPOA, the AVPV, and the SCN, which control reproductive success. The activity of these nuclei is also regulated by the balance of positive and negative effects of sex steroids [155][158]. The mechanism mediating both negative and positive feedback of estradiol is complex and still not fully understood. The abnormally high or persistently low estrogen plasma levels during reproductive senescence can impact HPG axis activity, resulting in reduced ovulation [174][177]. Interestingly, the changes in GnRH and kisspeptin secretion in HPG axis vary among species. In humans, it has been shown that high plasma concentrations of estrogen are associated with insensitivity of the HPG axis to estrogen feedback [175][176][178,179]. This, in turn, leads to an increase in GnRH [177][178][180,181]. It is important to note that these changes in HPG axis activity are caused by depletion of ovarian follicles in middle-aged women. In contrast to humans, aging acyclic rodents retain the follicles in their ovaries [179][180][181][182,183,184]. Instead, they show a reduction in hypothalamic GnRH cell numbers followed by alterations in LH surge that contribute to reproductive senescence [182][183][184][185,186,187]. The importance of the hypothalamus in regulating reproductive ability could be confirmed with transplantation experiments. Aged ovaries transplanted into young adult ovariectomized female rats, for example, result in restoration of ovulation [185][186][188,189]. Besides these differences, in both humans and rodents, the rise of FSH concentrations is a main feature of reproductive senescence [187][188][190,191]. Altered LH secretion patterns characterized by an increased duration and decreased frequency of LH pulses can also be observed in both acyclic rodents and premenopausal women [189][190][192,193]. Therefore, to fully understand the transition to menopause in humans, the use of rodent models in hypothalamic decline can be of great help.

Figure 2. The HPG (hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal) axis regulates the levels of sex hormones in the human body. In the hypothalamus, the AVPV and mPOA communicate with each other and receive input from SCN neurons. After stimulation with peak estrogen, mPOA neurons produce GnRH which is transported to the pituitary. The pituitary then produces LH and FSH in response to GnRH stimulation, which act on the gonads to induce the production of sex hormones. Unlike the testes, the ovaries have been reported to express a functional circadian clock and respond to humoral and neuronal signals independently of LH and FSH rhythms. The rhythmic production of estrogen and progesterone is therefore likely influenced by the peripheral ovarian clock, as well as by rhythmic LH and FSH levels [191][194]. Estrogen also can inhibit GnRH secretion and gene expression. Testosterone is produced in a rhythmic manner [192][195], but this rhythmicity is largely HPG axis driven. During a woman’s life, the number of follicles in the ovaries diminishes until extremely low follicle numbers trigger menopause. However, the influence of this process on the peripheral ovarian clock is yet to be fully understood.

5. Old Age

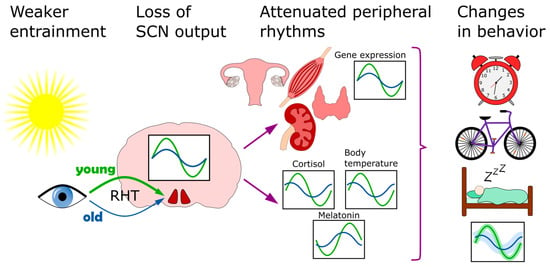

With increasing age, many physiological processes lose integrity, which results in a loss of resilience when faced with environmental challenges [205][208]. This increases the vulnerability to disease and, ultimately, death. One’s longevity is only partially (~15–30%) [206][209] explained by genetics, with a marked influence of personal history and life-long habits [207][210]. Between species, longevity varies largely. Across 26 different mammalian species with diverse lifespans, thousands of genes correlate with longevity. These can be divided into negatively correlated (mainly involved in energy metabolism and inflammation) and positively correlated (associated with DNA repair, microtubule organization and RNA transport). Remarkably, many genes in the negatively correlated group are under tight circadian regulation, suggesting that one adaptive value of the clock may lie in avoiding persistently high expression of such death promoting genes [208][211]. In addition to this, many ailments typically associated with old age also have a circadian component. These include neurodegeneration [209][212], cancer [210][213], cardiovascular diseases [211][214], hypertension [212][215] and others. Other dysfunctions include poor sleep [213][216] and poor cognition [214][217]. Aging both reduces the amplitude and phase advances of the circadian rhythms of the body, including sleep, body temperature, cortisol and melatonin [215][216][217][218][218,219,220,221] (Figure 3). These changes can be linked to circadian rhythm perturbation in both the SCN and peripheral tissues. Transplant experiments demonstrate the importance of the SCN in this context, as old animals that receive transplants of fetal SCN improve their rhythms of locomotor activity, body temperature, water consumption, pro-opiomelanocortin, corticotropin releasing hormone, and even show increased longevity [219][220][221][222,223,224]. More recent studies show how expression of neurotransmitters in the SCN diminishes with age. Both AVP and VIP levels are reduced in aged humans [222][223][224][225,226,227] and rodents [196][225][199,228]. In addition, GABAergic synapses also diminish in numbers in aged mice [226][229]. This understandably leads to lower amplitudes and lower levels of spontaneous firing activity [227][228][229][230,231,232]. Overall, this suggest that an aging SCN loses its internal synchrony [230][233], resulting in a loss of overall coherence of SCN outputs [231][234].

Figure 3. Circadian clock of the elderly. This affected on multiple levels. The entrainment of the clock by light becomes less efficient because of diminished light transmissibility of the lens. In the SCN, the neurotransmitter levels go down and overall coherence is disturbed. Downstream, the lower clock amplitude is also observed in several peripheral organs, including the skeletal muscle, kidney, thyroid and ovaries. As a result of these, and other, changes, the behavioral patterns of sleep/wake and activity also shift.