1. Introduction

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is detectable fragments of nucleic acids released from the cells into the circulation [

1]. CfDNA was first identified in the blood of a patient with leukemia by Labbe et al. in 1931 [

2], and then Mandel and Métais in 1948 found cfDNA in the plasma of healthy donors [

3]. These pioneering studies have shown that endogenous nucleic acids are permanently present in the bloodstream and that their quantities are changed in pathological conditions.

The heterogeneous fraction of circulating cfDNA includes genomic (cf-gDNA) and mitochondrial DNA (cf-mtDNA), depending on the origin [

4]. The sizes of cfDNA also vary significantly (80–10,000 bp, with normal peaks of 166 bp fragments for cf-gDNA and 20–100 bp for cf-mtDNA), depending on the mechanisms of fragmentation and release [

5]. The release of cfDNA from cells can occur passively as a result of various forms of cell death or via active secretion [

1,

6]. Most cfDNA enters the bloodstream through the secretion of extracellular vesicles, including exosomes, microparticles, or apoptotic bodies [

7]. Cell death caused by apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis contributes to the release of cfDNA into the bloodstream [

1,

8]. Programmed neutrophil death (NETosis) leading to the extrusion of nuclear-derived decondensed DNA (neutrophil extracellular traps, NETs) is also a source of cfDNA [

9]. Additionally, autophagy, erythroblast enucleation, and other processes promote the release of cfDNA into circulation [

1]. Thus, the majority of cfDNA in circulation is believed to originate from hematopoietic cells, including leukocytes and erythrocyte progenitors [

10]. However, under certain physiological or pathological conditions, a specific cfDNA of a different origin appears, such as from tumor cells in cancer or a damaged organ in trauma.

The interest in using cfDNA analyses to obtain diagnostic information has recently been growing [

11]. The analysis of cfDNA in biological fluids is considered a form of “liquid biopsy” because this approach allows for obtaining diagnostic information without invasive technologies [

8,

11]. The analysis of cfDNA has shown efficacy in prenatal screening for fetal chromosomal aneuploidies [

12], cancer diagnosis [

13], and the assessment of transplant rejection [

14]. Interestingly, in addition to data on the quantitative levels and genetic markers of circulating cfDNA, the differences in DNA methylation patterns, fragmentation profiles, and topological properties can also be used for diagnostic purposes [

11]. The analysis of cfDNA may also be useful in mental disorders.

The level of cfDNA is also of interest in association with inflammatory conditions. CfDNA is known to be part of the damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [

15]. CfDNA can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) promoting sterile inflammation [

16]. Inflammation is known to be associated with the pathogenesis of severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia [

17], bipolar disorder (BD) [

18], and depressive disorders (DDs) [

19]. However, the inflammation triggers in psychiatric disorders are still poorly understood, and cfDNA may be one of them.

2. Reports Characteristics

The list of reports included in the meta-analysis and their characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. Various analytical methods allow the detection of different types of cfDNA (cf-mtDNA and cf-gDNA) or total cfDNA. Therefore, researchers divided all reports depending on the type of analyzed cfDNA. As a result, the total cfDNA was investigated in 6 studies [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42] and cf-gDNA in three reports in the case of schizophrenia [

24,

36,

42]. There were insufficient data for a meta-analysis of cf-mtDNA in schizophrenia (only two studies) [

34,

35]. Cf-mtDNA was analyzed in BD and DDs. The data for other types of cfDNA were insufficient for a meta-analysis in BD and DDs. In particular, only one study on cf-gDNA was found for DDs [

36]. Accordingly, this meta-analysis analyzed the total cfDNA and cf-gDNA in schizophrenia, and cf-mtDNA was investigated in BD and DDs.

Table 1. Reports of circulating cfDNA concentrations in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depressive disorders included in the meta-analysis.

| Study |

Year |

DNA Type |

Sample |

Extraction Method |

Detection Method |

Population |

| Schizophrenia |

| Ershova et al. [39] |

2017 |

Total CfDNA |

Plasma |

Solvent extraction method |

FL, PicoGreen dye |

SZ 58/HC 30 |

| Jiang et al. [38] |

2018 |

Total CfDNA |

Plasma |

TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (spin-column) |

FCS |

SZ 65/HC 62 |

| Ershova et al. [37] |

2019 |

Total CfDNA |

Plasma |

Solvent extraction method |

FL, PicoGreen dye |

SZ 100/HC 96 |

| Jestkova et al. [40] |

2021 |

Total CfDNA |

Plasma |

Solvent extraction method |

FL, PicoGreen dye |

SZ 334/HC 95 |

| Ershova et al. [41] |

2022 |

Total CfDNA |

Plasma |

Solvent extraction method |

FL, PicoGreen dye |

SZ 100/HC 60 |

| Lubotzky et al. [42] |

2022 |

Total CfDNA and Cf-gDNA |

Plasma |

QIAsymphony DSP Circulating DNA Kit (magnetic particles) |

FL, bisulfite DNA treatment, PCR amplification followed by NGS |

FEP 29/HC 31 |

| Chen et al. [24] |

2021 |

Cf-gDNA |

Serum |

TianLong DNA Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: Alu repeats |

SZ 174/HC 100 |

| Qi et al. [36] |

2020 |

Cf-gDNA |

Serum |

TianLong DNA Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: Alu repeats |

SZ 164/HC 100 |

| Bipolar Disorder |

| Stertz et al. [25] |

2015 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Serum |

QIAmp DNA Mini Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: MT-ATP8 gene |

BD 20/HC 20 |

| Kageyama et al. [35] |

2018 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Plasma |

QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: MT-ND1 and MT-ND4 genes |

BD 28/HC 29 |

| Jeong et al. [43] |

2020 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Serum |

QIAmp DNA Mini Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: MT-ND1 gene |

BD 64/HC 41 |

| Kageyama et al. [44] |

2022 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Plasma |

QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: MT-ND1 and MT-ND4 genes |

BD 10/HC 10 |

| Depressive disorders |

| Lindqvist et al. [45] |

2016 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Plasma |

QIAmp 96 DNA Blood Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: MT-ND2 gene |

Suicide attempters 37/HC 37 |

| Kageyama et al. [35] |

2018 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Plasma |

QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: MT-ND1 and MT-ND4 genes |

MDD 109/HC 29 |

| Lindqvist et al. [47] |

2018 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Plasma |

QIAmp 96 DNA Blood Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: MT-ND1 and MT-ND4 genes |

MDD 50/HC 55 |

| Fernström et al. [46] |

2021 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Plasma |

QIAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR, target: MT-ND2 gene |

Current depression 236/HC 49 |

| Behnke et al. [48] |

2022 |

Cf-mtDNA |

Serum |

QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (spin-column) |

qPCR with multiple target |

MDD 24/HC 20 |

There was some heterogeneity across disease groups (

Table 1). Among the eight reports in the schizophrenia group, one report examined total the cfDNA and cf-gDNA in first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients [

42]. In the DDs group, three reports included patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) [

35,

47,

48], one report included individuals with current depression [

46], and one study included suicide attempters [

45].

Plasma, rather than serum, is known to be the preferred source for cfDNA analyses [

49]. The blood plasma was analyzed in most of the reports included in the meta-analysis (

Table 1). In particular, only 2 out of 8 reports in schizophrenia [

24,

36], 2 out of 4 in BD [

25,

43], and only 1 out of 5 in DDs [

48] were devoted to the analysis of cfDNA in serum. Plasma was used in all reports of total cfDNA in schizophrenia. Serum was used in 2 out of 3 reports of cf-gDNA in schizophrenia.

The cfDNA isolation and detection methods also differed in the included reports (

Table 1). The column method for cfDNA isolation was used in all reports for BD and DDs. In the case of schizophrenia, three of the eight studies used the column method [

24,

36,

38], four used organic solvents [

37,

39,

40,

41], and one used magnetic particles [

42] for DNA extraction. The fluorescent detection method was primarily used to analyze the total cfDNA in schizophrenia (only one report used fluorescence correlation spectroscopy) [

38]. The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method was mainly used to determine cf-gDNA in schizophrenia and cf-mtDNA in BD and DDs. Alu repeat amplification was used for the cf-gDNA analysis with qPCR [

24,

36]. The target genes for the cf-mtDNA analysis were as follows:

MT-ATP8,

MT-ND1,

MT-ND2, and

MT-ND4. The cfDNA concentration was presented in various units of measurement. Eight studies reported cfDNA concentrations as ng/mL (or pg/mL) [

24,

36,

37,

39,

40,

41,

42,

48], five as copies/µL [

35,

43,

44,

46,

47], two as GE/mL (or U/mL) [

25,

45], and one as nM [

38]. All selected studies were published between 2015 and 2022.

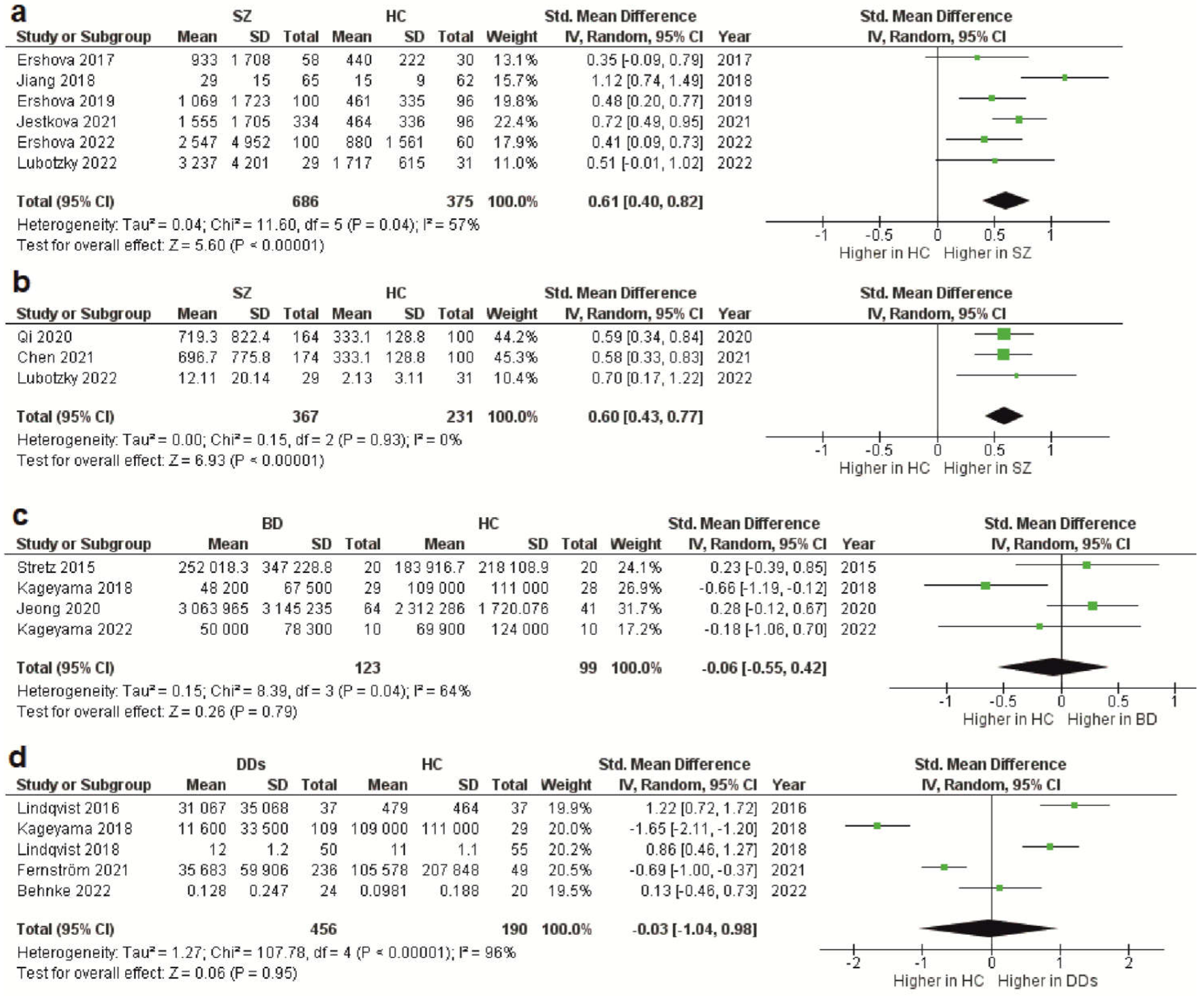

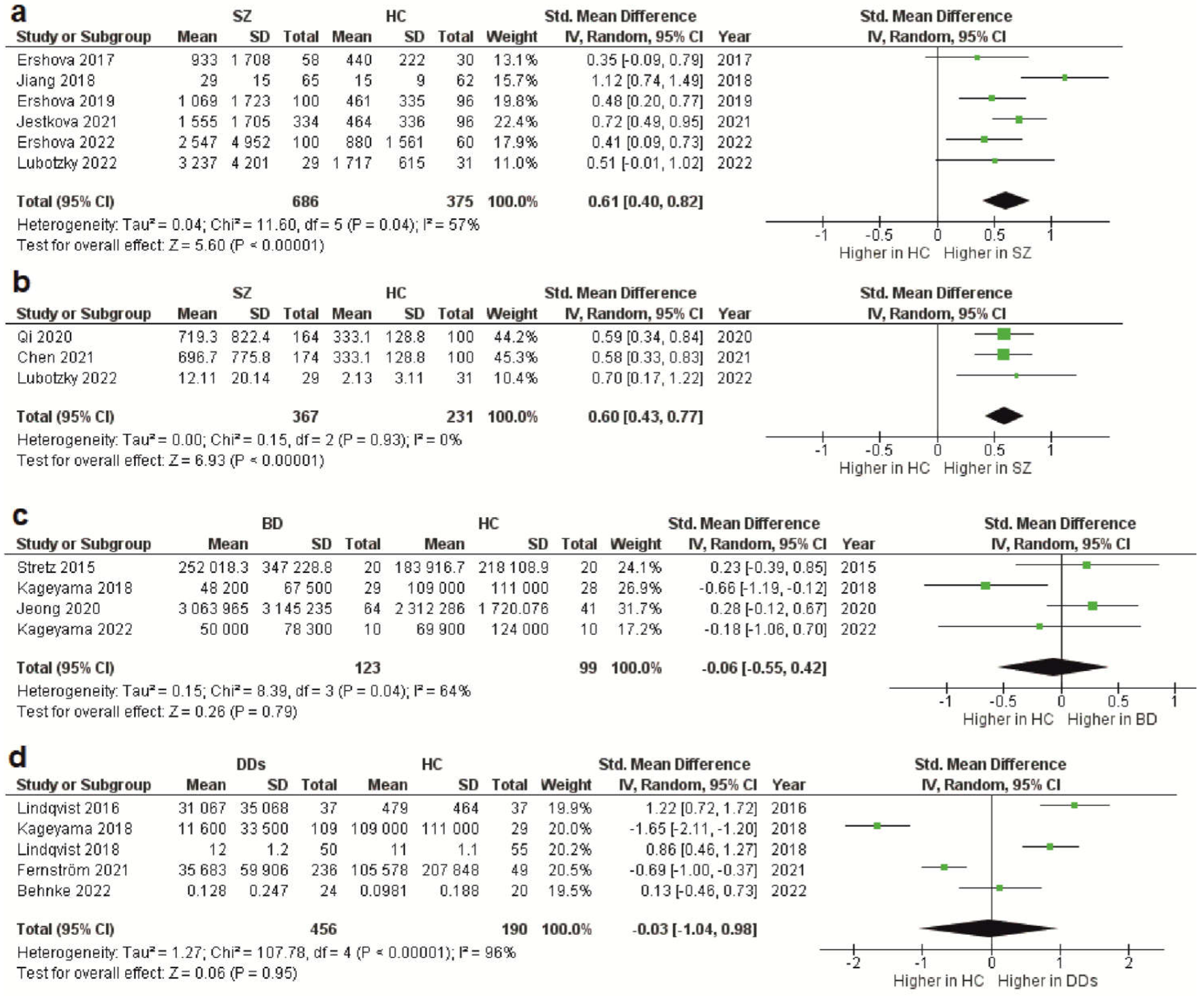

3. CfDNA Level in Schizophrenia

As stated above, the total cfDNA and cf-gDNA were analyzed in schizophrenia due to insufficient data existing for another type of cfDNA (cf-mtDNA). A meta-analysis of the circulating total cfDNA in schizophrenia pooled data from six studies with a total of 686 patients and 375 healthy controls. It has been shown that the circulating total cfDNA concentration in schizophrenia is significantly higher than in healthy donors (

Figure 1a). The SMD for the overall effect was 0.61 (95% CI = [0.40 to 0.82]), with moderate heterogeneity (Chi

2 = 11.6, df = 5,

p < 0.04; I

2 = 57%). The test for the overall effect also confirmed the significance of the differences (Z = 5.6,

p < 0.00001). No evidence of publication bias was observed using Egger’s test (

p = 0.773) and Begg’s test (

p = 0.851). The funnel plot analysis showed signs of asymmetry. The three reports on the left side of the graph were from the same research group using a similar method [

37,

39,

41]. Therefore, the observed asymmetry may indicate a publication bias. One report falling outside the confidence interval was probably related to the measurement methodology (fluorescence correlation spectroscopy) [

38]. Additionally, there was sample heterogeneity (one of the six reports analyzed FEP patients) [

42].

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing plasma and serum levels of total cfDNA in patients with schizophrenia (

a), cf-gDNA in schizophrenia (

b), cf-mtDNA in BD (

c), and cf-mtDNA in DDs (

d) compared with healthy controls. BD—bipolar disorder; CI—confidence interval; DDs—depressive disorders; SD—standard deviation; SZ—schizophrenia; HC—healthy controls.

The meta-analysis of circulating cf-gDNA in schizophrenia included three studies with a total of 367 patients and 231 healthy individuals. A meta-analysis showed that the cf-gDNA concentration in schizophrenia was significantly higher than in the controls (

Figure 1b). The SMD for the overall effect was 0.6 (95% CI = [0.43 to 0.77]). The test for the overall effect also confirmed the significance of the differences (Z = 6.93,

p < 0.00001). Interestingly, there was practically no heterogeneity in the report results (Chi

2 = 0.15, df = 2,

p < 0.93; I

2 = 0%). However, while Egger’s test (

p = 0.058) and Begg’s test (

p = 0.117) showed no evidence of bias, there were some indications of publication bias. In particular, the two reports had the same mean and standard deviation for the cf-gDNA for the group of healthy donors [

24,

36]. The funnel plot also confirmed this observation. Therefore, these results must be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, after removing one of the studies with the same group of healthy donors [

24], the meta-analysis results remained significant (SMD = 0.61, 95% CI = [0.38 to 0.84] with no heterogeneity (Chi

2 = 0.13, df = 1,

p < 0.72; I

2 = 0%); test for overall effect: Z = 5.23,

p < 0.00001). Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm the increased circulating cf-gDNA concentrations in schizophrenia.

4. CfDNA Level in Bipolar Disorder

Less reliable data were obtained for BD because only four studies were included in the meta-analysis, with a total of 123 patients and 99 healthy controls. Only the cf-mtDNA concentration was analyzed in a meta-analysis. The results indicated that the circulating cf-mtDNA concentration in BD is not statistically different from in healthy donors (

Figure 1c). The SMD for the overall effect was −0.06 (95% CI = [−0.55 to 0.42]), with moderate heterogeneity (Chi

2 = 8.39, df = 3,

p < 0.04; I

2 = 64%). The test for the overall effect also showed no significant differences (Z = 0.06,

p = 0.95). No evidence of publication bias was observed using Egger’s test (

p = 0.646) and Begg’s test (

p = 0.467). However, one report in the funnel plot was outside the confidence interval [

35], which may indicate a publication bias. Thus, more research is needed on cf-mtDNA and other types of cfDNA in BD.

5. CfDNA Level in Depressive Disorders

The meta-analysis in DDs included only data for the circulating cf-mtDNA. A meta-analysis pooled data from five studies with a total of 456 patients and 190 healthy controls. It has been shown that the cf-mtDNA concentrations in DDs are not significantly different from those in healthy donors (

Figure 1d). The SMD for the overall effect was −0.03 (95% CI = [−1.04; 0.98]). It is important to note that substantial heterogeneity was observed (Chi

2 = 107.78, df = 4,

p < 0.00001; I

2 = 96%). Egger’s test (

p = 0.622) and Begg’s test (

p = 0.2) showed no signs of bias. However, the funnel plot showed signs of publication bias, as many of the studies were outside the confidence intervals.

6. Conclusion

In summary, this meta-analysis provided evidence for high levels of total cfDNA and cf-gDNA in the plasma and serum of patients with schizophrenia compared with healthy individuals. In contrast, evidence for altered cf-mtDNA levels in BD and DDs was not found in this meta-analysis. However, the lack of significant differences may be partly caused by the small number of studies in BD and the hypothetical publication bias in DDs. Data on other types of cfDNA or total cfDNA in these psychiatric disorders are scarce. In particular, there are few studies on cf-mtDNA in schizophrenia or total cfDNA and cf-gDNA in BD and DDs. Therefore, further research should fill this knowledge gap. High levels of cfDNA in schizophrenia may be associated with chronic systemic inflammation in schizophrenia, as cfDNA has been found to trigger inflammatory responses.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing plasma and serum levels of total cfDNA in patients with schizophrenia (a), cf-gDNA in schizophrenia (b), cf-mtDNA in BD (c), and cf-mtDNA in DDs (d) compared with healthy controls. BD—bipolar disorder; CI—confidence interval; DDs—depressive disorders; SD—standard deviation; SZ—schizophrenia; HC—healthy controls.

The meta-analysis of circulating cf-gDNA in schizophrenia included three studies with a total of 367 patients and 231 healthy individuals. A meta-analysis showed that the cf-gDNA concentration in schizophrenia was significantly higher than in the controls (Figure 1b). The SMD for the overall effect was 0.6 (95% CI = [0.43 to 0.77]). The test for the overall effect also confirmed the significance of the differences (Z = 6.93, p < 0.00001). Interestingly, there was practically no heterogeneity in the report results (Chi2 = 0.15, df = 2, p < 0.93; I2 = 0%). However, while Egger’s test (p = 0.058) and Begg’s test (p = 0.117) showed no evidence of bias, there were some indications of publication bias. In particular, the two reports had the same mean and standard deviation for the cf-gDNA for the group of healthy donors [24,36]. The funnel plot also confirmed this observation. Therefore, these results must be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, after removing one of the studies with the same group of healthy donors [24], the meta-analysis results remained significant (SMD = 0.61, 95% CI = [0.38 to 0.84] with no heterogeneity (Chi2 = 0.13, df = 1, p < 0.72; I2 = 0%); test for overall effect: Z = 5.23, p < 0.00001). Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm the increased circulating cf-gDNA concentrations in schizophrenia.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing plasma and serum levels of total cfDNA in patients with schizophrenia (a), cf-gDNA in schizophrenia (b), cf-mtDNA in BD (c), and cf-mtDNA in DDs (d) compared with healthy controls. BD—bipolar disorder; CI—confidence interval; DDs—depressive disorders; SD—standard deviation; SZ—schizophrenia; HC—healthy controls.

The meta-analysis of circulating cf-gDNA in schizophrenia included three studies with a total of 367 patients and 231 healthy individuals. A meta-analysis showed that the cf-gDNA concentration in schizophrenia was significantly higher than in the controls (Figure 1b). The SMD for the overall effect was 0.6 (95% CI = [0.43 to 0.77]). The test for the overall effect also confirmed the significance of the differences (Z = 6.93, p < 0.00001). Interestingly, there was practically no heterogeneity in the report results (Chi2 = 0.15, df = 2, p < 0.93; I2 = 0%). However, while Egger’s test (p = 0.058) and Begg’s test (p = 0.117) showed no evidence of bias, there were some indications of publication bias. In particular, the two reports had the same mean and standard deviation for the cf-gDNA for the group of healthy donors [24,36]. The funnel plot also confirmed this observation. Therefore, these results must be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, after removing one of the studies with the same group of healthy donors [24], the meta-analysis results remained significant (SMD = 0.61, 95% CI = [0.38 to 0.84] with no heterogeneity (Chi2 = 0.13, df = 1, p < 0.72; I2 = 0%); test for overall effect: Z = 5.23, p < 0.00001). Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm the increased circulating cf-gDNA concentrations in schizophrenia.