Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Yusof Kamisah.

Parkia is a genus of flowering plants belonging to the family Fabaceae (subfamily, Mimosoideae) with pan-tropical distribution. The word Parkia was named after the Scottish explorer Mungo Park, who drowned in the Niger River, Nigeria in January 1805. The genus Parkia (Fabaceae, Subfamily, Mimosoideae) comprises about 34 species of mostly evergreen trees widely distributed across neotropics, Asia, and Africa.

- Parkia

- Mimosoideae

- traditional medicine

- secondary metabolite

1. Introduction

Parkia is a genus of flowering plants belonging to the family Fabaceae (subfamily, Mimosoideae) with pan-tropical distribution [1]. The word Parkia was named after the Scottish explorer Mungo Park, who drowned in the Niger River, Nigeria in January 1805 [2]. Thirty-one species from this genus were reported in 1995 [3]. Another four more species were discovered in 2009 [4]. Out of these species, 10 species found in Asia, four in Africa, and 20 in neotropics. Meanwhile, according to a plant list (2018), 80 scientific names are recorded from the genus Parkia containing 41 accepted names and 39 synonym species (The Plant List, 2018). These plants bear fruits called pods. Each pod contains up to 25–30 seeds. Many species from Parkia have been reported to be rich in carbohydrate [5[5][6][7],6,7], protein [8,9,10][8][9][10] and minerals [11,12,13,14][11][12][13][14].

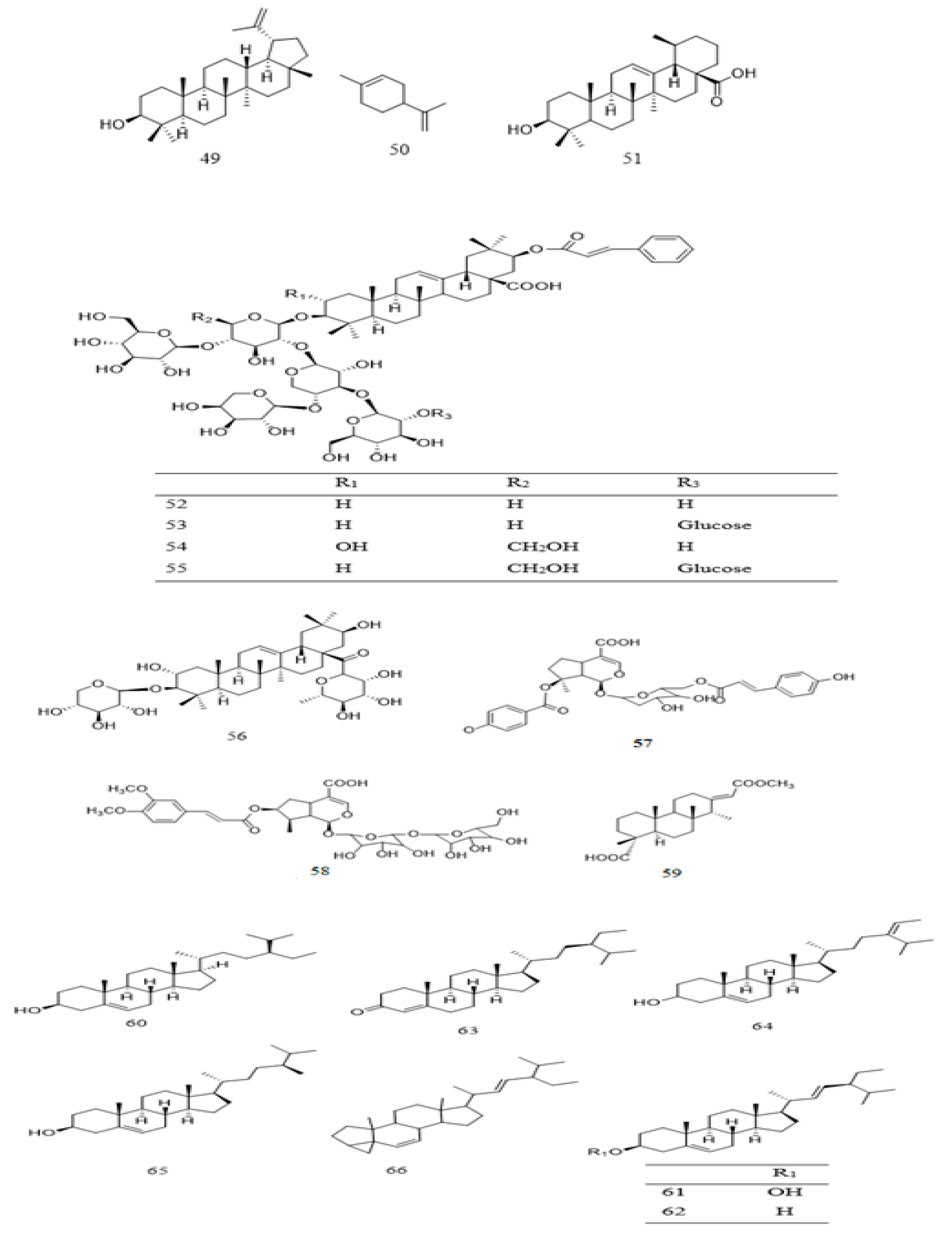

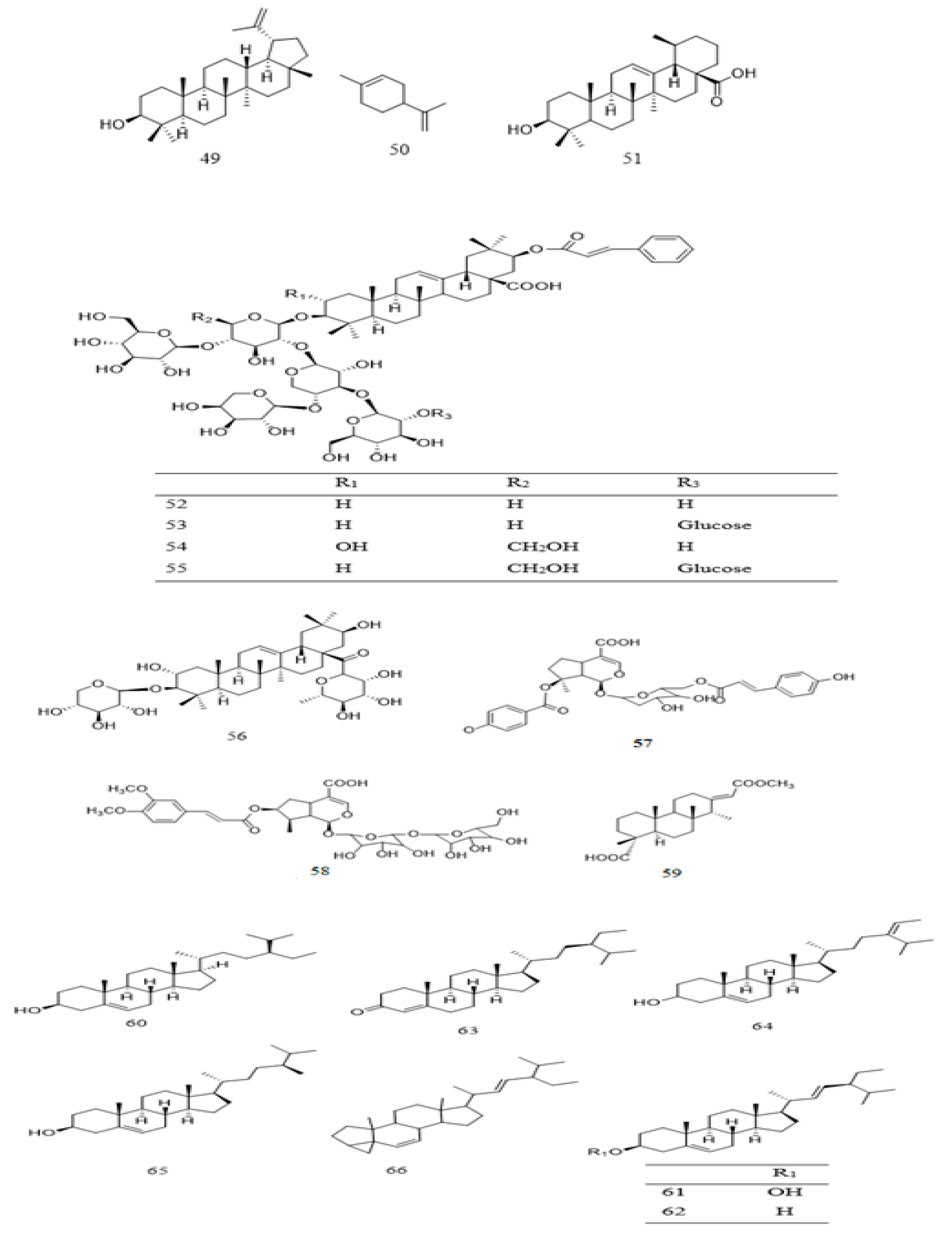

125]. In addition, some minor components, such as 82–84 are also identified. Meanwhile, 132 content in P. speciosa seed was reported to be 4.15 mg/100 g [37][85], but that of P. biglobosa in a recent study was found to be much higher (53.47 mg/100 g). Phospholipid content of P. biglobosa seeds was about 451 mg/100 g [122]. The seeds also contain palmitic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, arachidic acid, and linoleic acid, the most abundant fatty acid [22,121,130][22][121][130]. Similar fatty acids are also reported in the raw seeds of P. roxburghii chloroform/methanol extract, in addition to total free phenol (0.56 g/100 g seed flour) and tannins (0.26 g/100 g seed flour) contents [41][87].

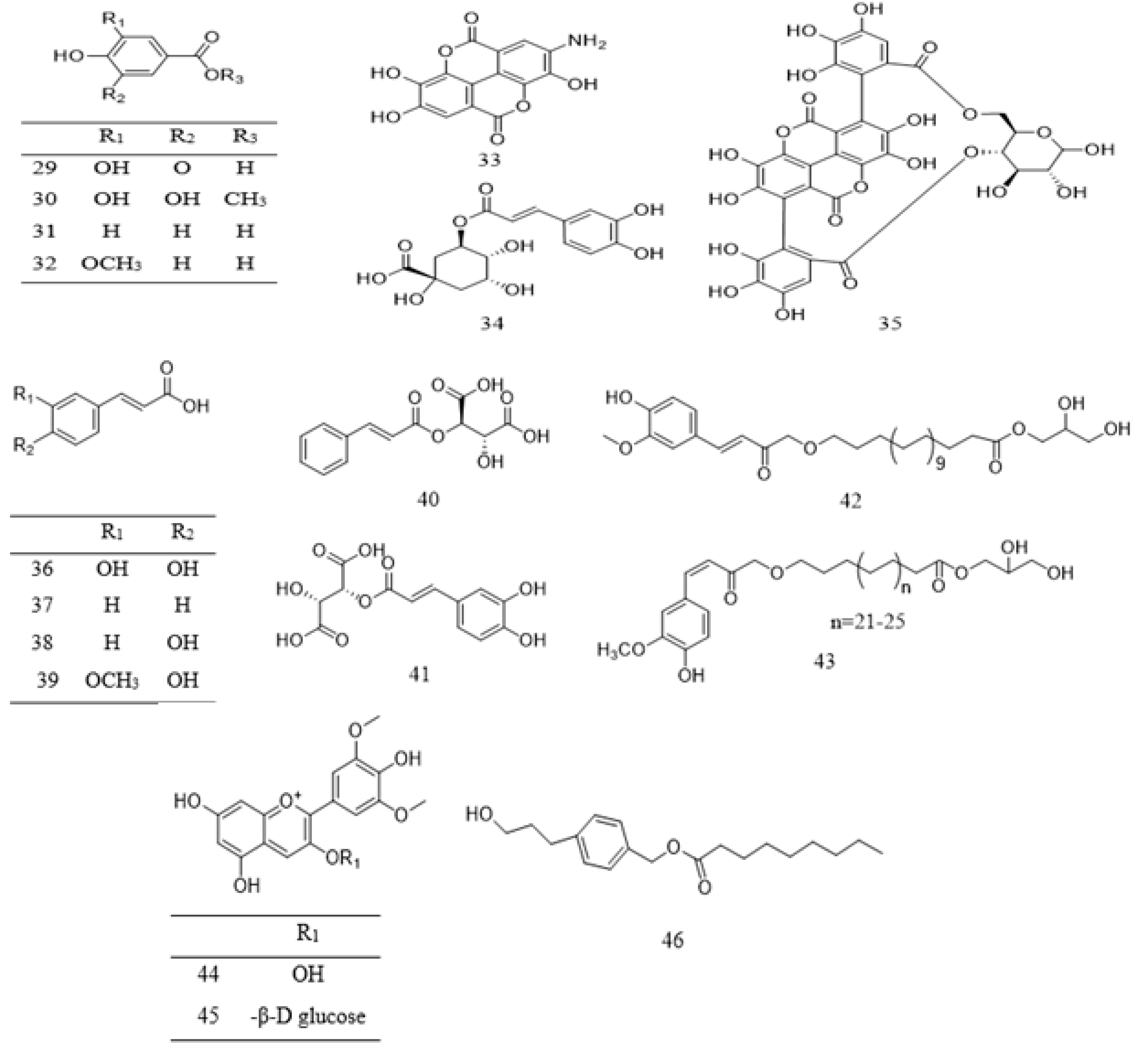

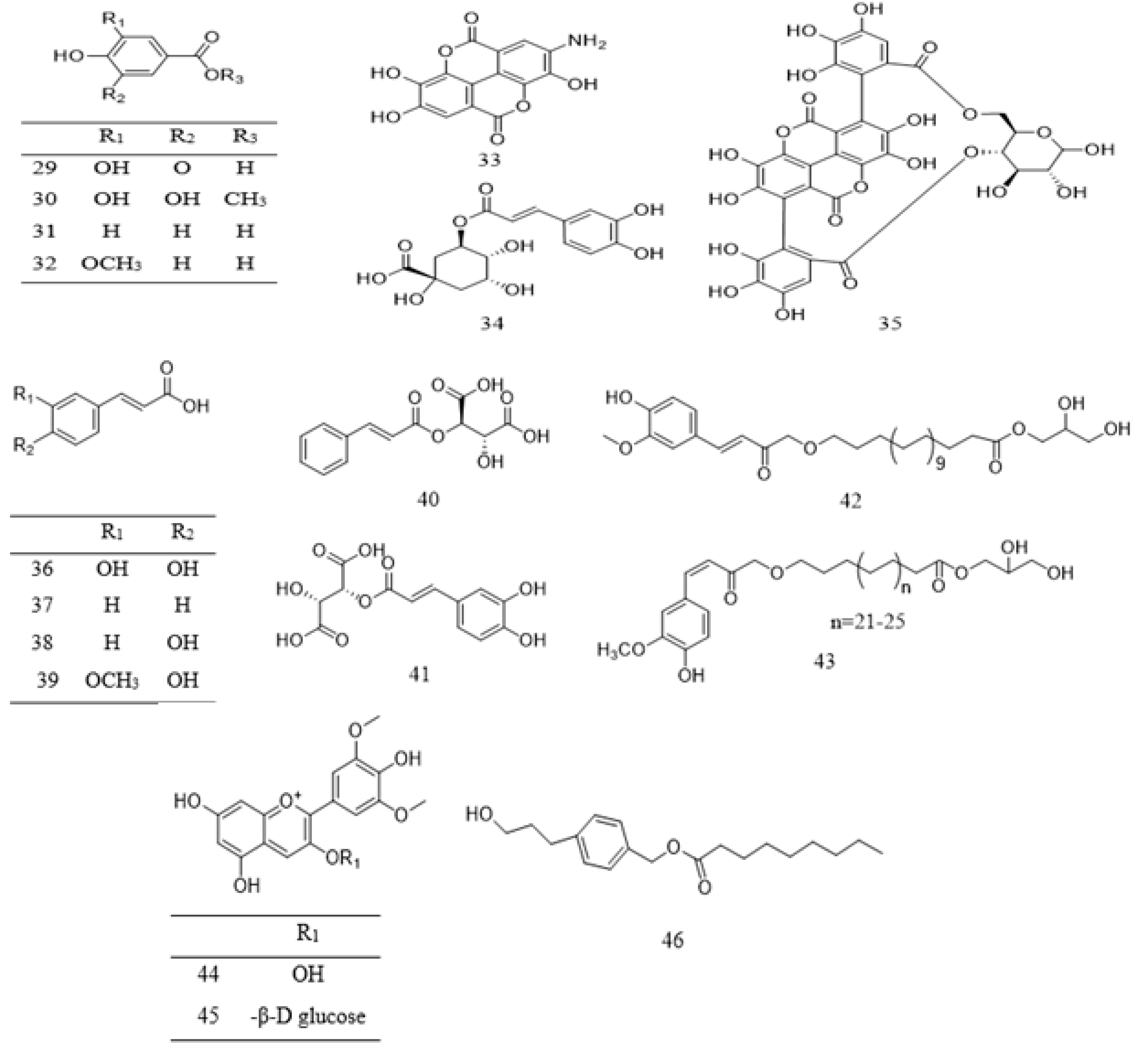

Steroidal compounds are also reported in the genus of Parkia (Table 2 and Figure 43). β-Sitosterol (60) is one of the major components in P. speciosa [120] and P. biglobosa seeds [121]. The steroid together with stigmasterol are purified from recrystallization of chloroform/methanol fraction of P. speciosa seeds. Its composition in P. biglobosa seeds was reported to be about 377 mg/100 g dry weight [122]. It is also purified from methanol extract of P. javanica leaves [42][88]. Apart from 60, 61, and 65, which are present in P. javanica and/or P. biglobosa, all other steroids 62–64 and 66 reported from different studies are found in P. speciosa seeds. Other than β-sitosterol (60), stigmasterol (61), and campesterol (65) are also among the numerous compounds identified from the seeds of P. speciosa [117,119,120,124][117][119][120][124]. The percentage composition of 60, 61, 62 and a triterpenoid 49 in the plant was reported as 3.42%, 2.18%, 2.29%, and 0.71% w/w, respectively [37][85]. In the case of P. biglobosa, the percentage composition of 60, 61 and 62 in the seeds is higher with values of 55.7%, 3.42%, 37.1% for the unfermented, and 56.8%, 3.38%, 35.9% for the fermented, respectively, indicating that fermentation process may lower 61 and 62, but increases 60 contents [129]. Meanwhile, Akintayo (2004) had recorded 60 as the most abundant compound in P. biglobosa seeds, constituting approximately 39.5% w/w. Compound 60 was isolated as a pure compound through column chromatographic separation of benzene fraction of P. bicolor leaves [42][88].

Steroidal compounds are also reported in the genus of Parkia (Table 2 and Figure 43). β-Sitosterol (60) is one of the major components in P. speciosa [120] and P. biglobosa seeds [121]. The steroid together with stigmasterol are purified from recrystallization of chloroform/methanol fraction of P. speciosa seeds. Its composition in P. biglobosa seeds was reported to be about 377 mg/100 g dry weight [122]. It is also purified from methanol extract of P. javanica leaves [42][88]. Apart from 60, 61, and 65, which are present in P. javanica and/or P. biglobosa, all other steroids 62–64 and 66 reported from different studies are found in P. speciosa seeds. Other than β-sitosterol (60), stigmasterol (61), and campesterol (65) are also among the numerous compounds identified from the seeds of P. speciosa [117,119,120,124][117][119][120][124]. The percentage composition of 60, 61, 62 and a triterpenoid 49 in the plant was reported as 3.42%, 2.18%, 2.29%, and 0.71% w/w, respectively [37][85]. In the case of P. biglobosa, the percentage composition of 60, 61 and 62 in the seeds is higher with values of 55.7%, 3.42%, 37.1% for the unfermented, and 56.8%, 3.38%, 35.9% for the fermented, respectively, indicating that fermentation process may lower 61 and 62, but increases 60 contents [129]. Meanwhile, Akintayo (2004) had recorded 60 as the most abundant compound in P. biglobosa seeds, constituting approximately 39.5% w/w. Compound 60 was isolated as a pure compound through column chromatographic separation of benzene fraction of P. bicolor leaves [42][88].

2. Traditional Medicinal Uses

Parkia species are being used across all tropical countries to cure different ailments. Virtually, all parts of Parkia plants are utilized traditionally for different medicinal purposes. The materials of different parts of Parkia plants are processed as paste, decoction, and juice for the treatment of various ailments (Table 1). Almost all reported Parkia species are used in different forms to cure diarrhea and dysentery [15]. Different parts of P. biglobosa, P. clappertoniana, P. roxburghii, and P. speciosa are reported to be traditionally used for the treatment of diabetes [16,17,18][16][17][18]. Furthermore, skin-related diseases, such as eczema, skin ulcers, measles, leprosy, wound, dermatitis, chickenpox, scabies, and ringworm are treated using leaves, pods, and roots of P. speciosa and P. timoriana [19,20,21][19][20][21]. The stem barks of P. bicolor, P. clappertoniana, P. biglobosa, P. roxburghii as well as roots of P. speciosa are applied in the form of paste and decoction to treat different skin problems [22,23,24,25][22][23][24][25]. Decoction and paste of stem bark, pod, or root of P. biglobosa and P. speciosa are used to treat hypertension [22,26,27][22][26][27]. Moreover, stem barks of P. bicolor, P. biglobosa and leaves of P. speciosa are used for severe cough and bronchitis [28,29,30][28][29][30]. These aforementioned uses suggested that Parkia plants are likely to contain constituents with broad and diverse biological activities, such as antidiabetic, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, and anti-inflammatory.Table 1.

The medicinal uses of plants from genus

Parkia

.

| Species | Part Used | Method of Preparation | Medicinal Uses | Region/Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. bicolor | Stem bark | Pulverized powder | Wound healing | West coast of Africa and Nigeria |

Figure 54.

Structural formulas of cyclic polysulfides

81

–

93

, as previously listed in

Table 2

.

4. Pharmacological Activities of Parkia Species

Numerous bioactive constituents such as phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, and volatile compounds present in Parkia species may account for its various health benefits, and therefore responsible for the vast pharmacological properties (Table 3). However, only few species have been extensively studied.Table 3.

Pharmacological activities of

Parkia species

extracts and fractions.

| Activity | Species | Part | Type of Extract/Compound | Key Findings | References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial | P. biglobosa | Leaf, stem bark, and root | Methanolic and aqueous | Active against S. aureus, B. subtilis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa | [23] | ||||||

| . | [ | 38 | ] | [ | 44] | Tree | Diarrhea, dysentery | Southwest Nigeria | [55][31] | ||

| P. biglobosa | Root bark | Aqueous and methanol | Active against E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa. Activity: Aqueous > methanol |

[34][82] | Stem barks | Decoction | Bad cough, measles, and woman infertility |

||||

| P. biglobosa | Leaves and pod | Aqueous and ethanol | Active against S. aureus, E. aerogenes, S. typi, S. typhimurium, Shigella spp., E. coli, and P. aeruginosa | Cameroon | (bacteria), Mucor spp., and Rhizopus spp. (fungi)[ | [133][131]28] | |||||

| Stem barks | Decoction | Diarrhea and skin ulcers | |||||||||

| P. biglobosa | Ghana | [ | Bark and leaves | Hydro-alcohol and aqueous | Active against E. coli, S. enterica, and S. dysenteriae. Activity: hydroalcoholic > aqueous | [65][42]56][32] | |||||

| P. biglobosa | Roots & bark | Paste | Dental disorder | Ivory Coast | |||||||

| P. speciosa | Seeds | Water suspension | Active against S. aureus, A. hydrophila, S. agalactiae, S. anginosus, and V. parahaemolyticus isolated from moribund fishes and shrimps | [143][132 | [29] | ||||||

| ] | Seed and stem bark | Fresh seeds | |||||||||

| P. speciosa | Seed peel | Ethyl acetate (EA) Hexane | Fish poison | West Africa | Ethanol[57 |

EA: Four times higher than streptomycin against S. aureus and three times higher for E. coli,58][33][34] | |||||

| . Hexane: 50% inhibitory ability of streptomycin for both bacteria. Ethanol: no inhibition | [ | 148 | ] | [133] | Root | Decoction combined with other plants | Infertility | ||||

| P. speciosa | Pod extract and its silver | Nigeria | Aqueous | Pod: active against P. aeruginosa Silver particles: active against P. aeruginosa | [145][134][58][34] | ||||||

| Bark infusion with lemon | Diarrhea | Nigeria | [59][35] | ||||||||

| P. speciosa | Sapwood, heartwood, and bark | Methanol | Bark: Active against G. trabeum. Sapwood and heartwood: No effect | [147][135] | Stem bark | Anti-snake venom | Nigeria | ||||

| P. speciosa | Seeds | Chloroform, petroleum ether, Aqueous and methanol | Active against H. pylori except aqueous extract. Activity: chloroform > methanol > petroleum ether | [222][136] | [60][36] | ||||||

| Bark | Paste, decoction | Wound healing leprosy, hypertension, mouth wash, toothpaste | Nigeria | ||||||||

| P. speciosa | Seed | Methanol Ethyl acetate |

Methanol: active against H. pylori. Ethyl acetate: active against E. coli Both: no effect on S. typhimurium, S. typhi, and S sonnei | [ | 22 | [144][,23][22][23] | |||||

| 137 | ] | Leaves and roots | Eyesore | Lotion | Gambia | ||||||

| P. javanica | Stem bark | Methanol | Good inhibitory activity against E. coli, S. aureus S. pyogenes found in chronic wound | [223][138] | [23] | ||||||

| Bark | Hot decoction | Fever | Gambia | [23 | |||||||

| P. javanica | Stem bark | Methanol | Active against four Vibrio cholerae strains | ] | |||||||

| [ | 224 | ] | [ | 139] | Bark | Decoction | Malaria, diabetes, amenorrhea, and hypertension | Senegal, Mali, Ghana Togo, and South Africa | [11,40,61,62,63] | ||

| P. javanica | Leaves | Gold and silver nanoparticles | Good inhibitory activity against S. aureus | [ | 11][37 | [151]][38][39][40] | |||||

| [ | 140 | ] | Roots and bark | Decoction of the roots with Ximenia americana | Weight loss | Burkina Faso | [ | ||||

| P. javanica | Bark | 64 | ] | [ | 41] | ||||||

| Methanol extract and semi-polar fractions (chloroform and ethyl acetate) | Active against | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | . Chloroform showed the best activity | [97][76] | Stem bark | Boiled bark | Diarrhea, conjunctivitis, severe cough, and leprosy | West Coast Africa | [ | ||

| P. javanica | 23 | , | Seeds, leaves and skin pods | Aqueous | Active against S. aureus, A. hydrophila, and S. typhimurium Not active against E. coli | [152][14165,66][23][42][43] | |||||

| ] | Leaves | Decoction | Violent colic chest and muscular pain | Northern Nigeria | |||||||

| P. clappertoniana | Leaves and barks | Ethanol | Active against Salmonellae and Shigella | [73][51 | [38][44] | ||||||

| ] | bark | Infusion | Dental caries and astringent | Guinea Bissau | |||||||

| P. clappertoniana | Stem bark and leaves | Aqueous and methanol | Active against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Methanol extract was more potent |

[71] | [67][45] | ||||||

| [ | 49 | ] | P. biglandulosa | Seed bark | |||||||

| P. biglandulosa | Saponins | Leaf | Astringent | Methanol | Active against E. coli, India | P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus | [154][142][68][46] | ||||

| Stem bark | Hemagglutination, ulcer | ||||||||||

| P. filicoidea | Stem barks | Aqueous, acetone and ethanol | Active against | India | S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, S. viridans and B. subtilis. Not active against E. coli | [50][[69][47] | |||||

| 96 | ] | Tree | Inflammation and ulcer | India | |||||||

| P. bicolor | Leaves | Ethyl acetate, ethanol and aqueous | Active against E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, A. niger, B. cereus and a fungus, C. utilis | [ | 70 | [23]][48] | |||||

| P. clappertoniana | Tree | Hypertension | Southwest Nigeria | ||||||||

| P. bicolor | Roots | Methanol, ethyl acetate and Aqueous | Active against C. diphtheria, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, S. typhi, and S. pyogenes | [28] | [55][31] | ||||||

| P. pendula | Root | Seeds | LectinDental caries and conjunctivitis | African | [71 | Reduced cellular infectivity of human cytomegalovirus in human embryo lung (HEL) cells. | [225][143],72][49][50] | ||||

| Seed | Crudely pounded | Labor induction | Ghana | [17] | |||||||

| Hypoglycemic | P. speciosa | Seeds and pods | Chloroform | Strong glucose-lowering activity in alloxan-induced diabetic rats Activity: seeds > pod |

[ | Tree | Diarrhea | Kaduna and Nigeria | [73][51] | ||

| Leaves and bark | Maceration | Epilepsy | Northern Nigeria | [74][52] | |||||||

| Stem bark | Chickenpox and measles | Southwest Nigeria | [24] | ||||||||

| 157 | ] | [ | 144 | ] | |||||||

| P. speciosa | Rind, leaves and seeds | Ethanol | Inhibited α-glucosidase activity in rat Activity: rind > leaf > seed |

[158][145] | |||||||

| P. speciosa | Seed | Chloroform | Reduced plasma glucose levels in alloxan-induced diabetic rats | [120] | |||||||

| P. biglobosa | Fermented seeds | Methanol and aqueous | Reduced fasting plasma glucose in alloxan-induced diabetic rats | [160,161][146][147] | Tree | Diabetes, leprosy, and ulcers | Ghana | [75][53] | |||

| P. biglobosa | Seeds | Protein | Significantly increased lipid peroxidation product levels in brain and testes of diabetic rats | [226][148] | Tree | Mouthwash and toothache | Nigeria | ||||

| P. biglobosa | Seeds | Methanol and fractions (chloroform and n-hexane) | Showed glucose-lowering effect Activity: chloroform > methanol > n-hexane |

[40][37] | [76][54] | ||||||

| Tree | Eczema and skin diseases | Nigeria | |||||||||

| P. javanica | Fruits | Ethyl acetate fraction | Reduced blood glucose inhibited α-glucosidase and α-amylase in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats | [ | [77][55] | ||||||

| 18 | ] | Bark | Infusion | Hernia | Ghana | [75 | |||||

| Antitumor/ Anticancer | ] | [ | 53 | ] | |||||||

| P javanica | Fruits | Aqueous methanol | Increased apoptosis in sarcoma-180 cancer cell lines | [ | 227][149] | P. pendula | Leaves bark | Genital bath | Netherland | [78 | |

| P javanica | Seeds | Methanol | Caused 50% death in HepG2 (liver cancer cell) but not cytotoxic to normal cells | [44][90] | ][56] | ||||||

| Bark | Decoction | Malaria | Brazil | [79 | |||||||

| P javanica | ] | [ | 57 | ] | |||||||

| Seeds | Lectin | Inhibited proliferation in cancerous cell lines; P388DI and J774, B-cell hybridoma and HB98 cell line | [ | 173][150] | P. speciosa | Seed | |||||

| P. speciosa | Eaten raw or cooked oral decoction | Seed coats | Diabetes | Methanol extractMalaysia | Demonstrated selective cytotoxicity to MCG-7 and T47D (breast cancer), HCT-116 (colon cancer) | [228][151][80][58] | |||||

| Leaves | Pounded with rice and applied on the neck | Cough | Malaysia | [30] | |||||||

| P. speciosa | Pods | Methanolic ethyl acetate fraction | Showed selective cytotoxicity on breast cancer cells MCF-7 | [170][152] | Root | Decoction | Skin problems | Southern Thailand | [ | ||

| P. biglobosa | 21 | ] | |||||||||

| Leaves and stem | Methanol | Antiproliferative effect in human cancer cells T-549, BT-20, and PC-3 | [ | 174][153] | Root | Decoction taken orally | Hypertension and diabetes | Malaysia | [26] | ||

| P. filicoidea | Leaves | Methanol | Antiproliferative effect in in human cancer cells T-549, BT-20, and PC-3 | [174][153] | Fruit | Eaten raw | Diabetes | Malaysia | [30] | ||

| Antiproliferative and anti-mutagenic | P. biglandulosa | Seeds | Lectin | T cell mitogen and antiproliferative against P388DI and J774 cancer cell lines | [173][150] | Seed | Eaten raw | Detoxification and hypertension | Singapore | [ | |

| Antihypertensive | P. speciosa | 81 | ] | [ | 59] | ||||||

| Seeds | Aqueous | Showed moderate ACE-inhibitory activity in in vitro | [ | 191 | ][154] | Ringworm | Malaysia | [ | |||

| P. speciosa | Seeds | Peptide | Inhibited angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in rats. No effect observed in non-hydrolyzed samples | [189,190][155][156] | 82][60] | ||||||

| Leaf | Decoction | Dermatitis | Indonesia | ||||||||

| P. speciosa | Pods | Methanol | [ | 20 | Prevented the increases in blood pressure and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and restored nitric oxide in hypertensive rat model | [112]] | |||||

| Root | |||||||||||

| P. biglobosa | Oral decoction | Stem bark | Toothache | AqueousMalaysia | Induced hypotension in adrenaline-induced hypertensive rabbits | [181[27] | |||||

| ] | [ | 157 | ] | Tree | Heart problem, constipation and edema | India | |||||

| P. biglobosa | Roasted and fermented seeds | Aqueous | Induced relaxation in rat aorta precontracted with phenylephrine in the presence or absence of endothelium. | [180][158] | [83,84][61][62] | ||||||

| Leaves | Dermatitis | Indonesia | [85][63] | ||||||||

| Seed | Loss of appetite | Indonesia | [86][64] | ||||||||

| Seed | Cooked | Kidney disorder | West Malaysia | [87][65] | |||||||

| P. timoriana | Bark and twig | Decoction of bark and twig paste | Diarrhea, dysentery, and wound | India | [88][66] | ||||||

| Bark | Decoction used to bath | Fever | Gambia | [89][67] | |||||||

| Pulp bark | Mixed with lemon | Ulcer and wound | Gambia | [89][67] | |||||||

| Fruit | Diabetes | Thailand | [90][68] | ||||||||

| Pod | Pounded in water | Hair washing, skin diseases, and ulcers | India | [19] | |||||||

| Bark and leaves | Head washing, skin diseases, and ulcers | India | [19] | ||||||||

| Bark | Decoction with Centella. asiatica and Ficus glomerata | Diabetes | India | [16] | |||||||

| P. roxburghii | Tree | Tender pod and bark taken orally | Diarrhea, dysentery, intestinal disorder, and bleeding piles | India | [91][69] | ||||||

| The fruit or young shoot | Green portion of the fruit mixed with water to be taken orally | Dysentery, diarrhea, food poisoning, wound, and scabies | India | [92][70] | |||||||

| Seed | Grounded and mixed with hot water | Postnatal care, diarrhea, edema and tonsillitis | Malaysia | [93][71] | |||||||

| Pod | Diabetes, hypertension, and urinary tract infections | India | [18] | ||||||||

| Leaves, pod, peals, and bark | Diarrhea and dysentery | India | [94][72] | ||||||||

| Stem bark | Hot water extraction | Diarrhea and dysentery | India | [95][73] | |||||||

| Bark | Turn into paste | Used as plaster for eczema | India | [25] | |||||||

| P. javanica | Bark, pod, and seed | Taking orally as vegetable | Dysentery and diarrhea | India | [15] | ||||||

| Tree | Inflammation | India | [96][74] | ||||||||

| Bark fruit | Dysentery and piles | India | [51][75] | ||||||||

| Stomachache and cholera | India | [97][76] | |||||||||

| Bark and leaves | Lotion | Sores and skin diseases | [98][77] | ||||||||

| Tree | Diarrhea, cholera dysentery, and food poisoning | India | [99][78] |

3. Phytochemistry of Genus Parkia

Among the numerous species of Parkia plant, the chemistry of only few are known. However, different parts of the reported ones have been validated as good sources of phenolic compounds [11[11][79][80],31,32], saponins [33[81][82][83],34,35], terpenoids [35,36,37][83][84][85], steroids [23,38,39][23][44][86], tannins [38,39[37][44][86],40], fatty acids [23[23][87],41], and glycosides [42,43,44][88][89][90]. Various phytochemicals are found in the stem barks, leaves, seeds, and pods of these plants. The stem bark of P. biglobosa is reported to contain phenols, flavonoids, sugars, tannins, terpenoids, steroids, saponins [11[11][44],38], alkaloid, and glycosides [35,43[83][89][91],45], while the leaves contain glycosides, tannins, and alkaloids in trace amount [11,23[11][23][92],46], in addition to flavonoids, phenols, and anthraquinones [47][93]. Phytochemical screening of the seeds shows the presence of saponins, alkaloids, flavonoids, polyphenols, terpenoids, glycosides and tannins [48,49][94][95]. Fermentation or roasting of P. biglobosa seeds results in the alteration of the bioactive components. P. bicolor leaves contain chemical constituents similar to that of P. biglobosa such as glycosides, tannin, and alkaloids in trace amount [23]. The stem bark of P. bicolor contains alkaloids, tannins, saponins, glycosides, flavonoids, and terpenoids [35][83], while P. biglandulosa contains tannins, saponins, and glycosides, and P. filicoidea possesses flavonoids, sugars, saponins, and tannins [50][96]. The seed of P. javanica contains flavonoid, saponins, alkaloids, terpenoids, anthraquinones, steroids, and glycosides [44][90]. The pods are reported to have tannins, flavonoids, and saponins, all of which are significantly diminished when subjected to various processing methods, such as ordinary and pressure cooking methods [51,52][75][97]. Alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, and tannins are present in the whole plant of P. clappertoniana [31][79]. Phytochemical analysis of the leaves of P. platycephala revealed the presence of phenols, terpenoids, flavonoids [53][98], tannins and saponins [54][99]. Furthermore, flavonoids, alkaloids, phenols, and terpenoids were reported to be present in all parts of P. speciosa plant [37][85]. Phytochemicals (primary and secondary metabolites) are well known for their vast medicinal benefits to plants and human [100]. The primary metabolites—such as carbohydrate, proteins, chlorophyll, lipids, nucleic, and amino acids [101,102,103][101][102][103]—are responsible for plants’ biochemical reactions such as respiration and photosynthesis [102]. The secondary metabolites are majorly alkaloids, phenols, terpenoids, flavonoids, saponins, steroids, tannins, and glycosides, which play important roles in protecting the plants against damages and improving plant aroma, coloration and flavor [101[101][103],103], The phytochemicals are present in various parts of the plants especially in the three major parts viz. the leaves, stems and roots. Their percentage composition in each plant may vary depending on environmental conditions, variety and processing methods [101]. Previous studies have shown that phenolic compounds are the most abundant and widely distributed phytoconstituents (45%), followed by steroids and terpenoids (27%), and alkaloids (18%) [101,104][101][104]. Alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, and phenolic compounds are the most common constituents that have been studied in phytochemistry [104,105][104][105]. Several compounds from these classes have been identified and investigated from Parkia plants for various pharmacological activities. Despite the enormous reports on the phytochemical screening of different species from the genus Parkia, structure identification and purification of compounds from these species are scarcely reported compared to other genera. The compounds were identified using high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detector (HPLC-DAD), liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LCMS), flow analysis-ionization electrospray ion trap tandem mass spectrometry (FIA-ESI-IT-MS), gas chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC/ToF-MS), high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ion mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS), and chromatographic purification from the fraction and characterization through nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).3.1. Polyphenolic Compounds

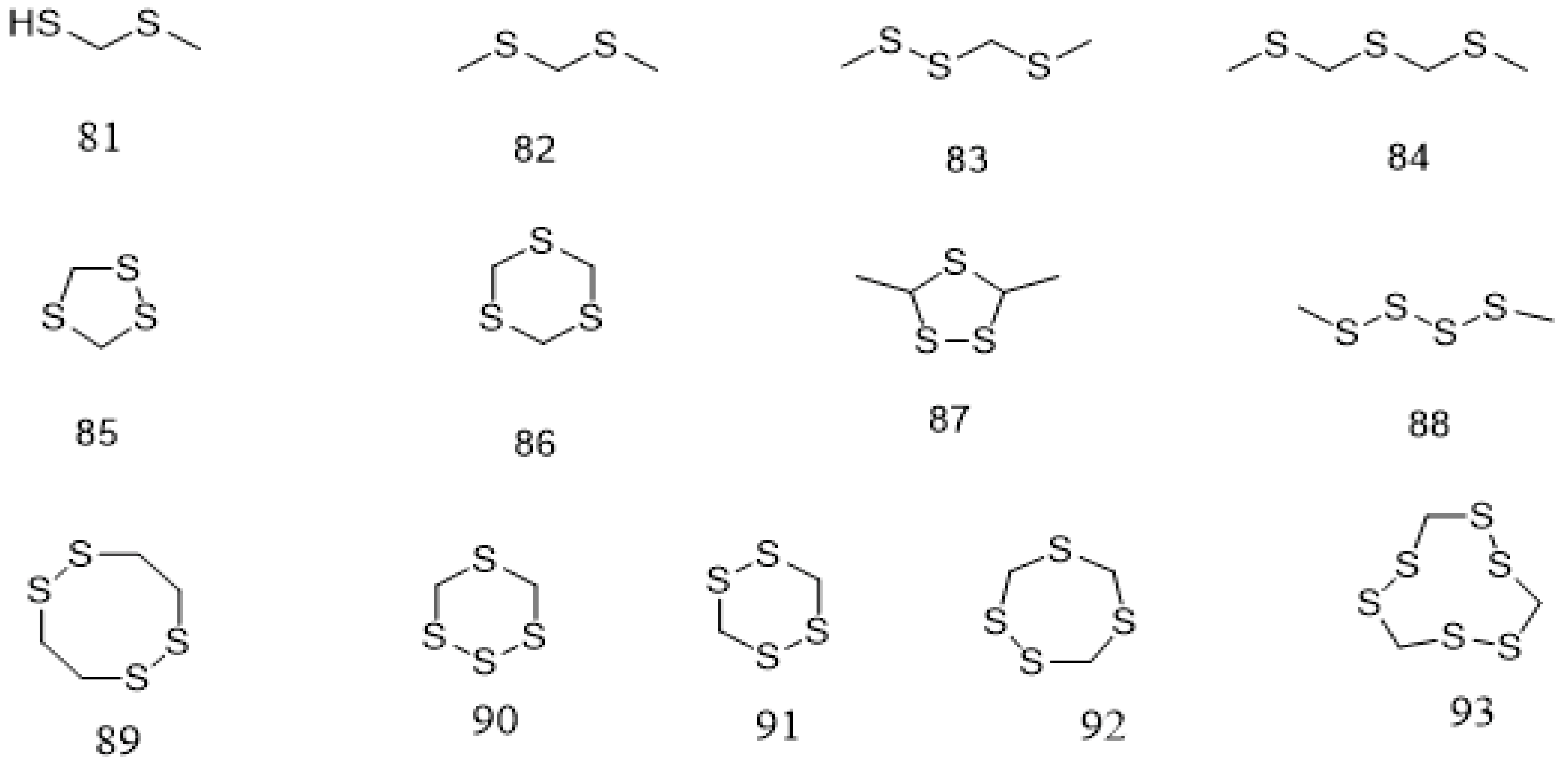

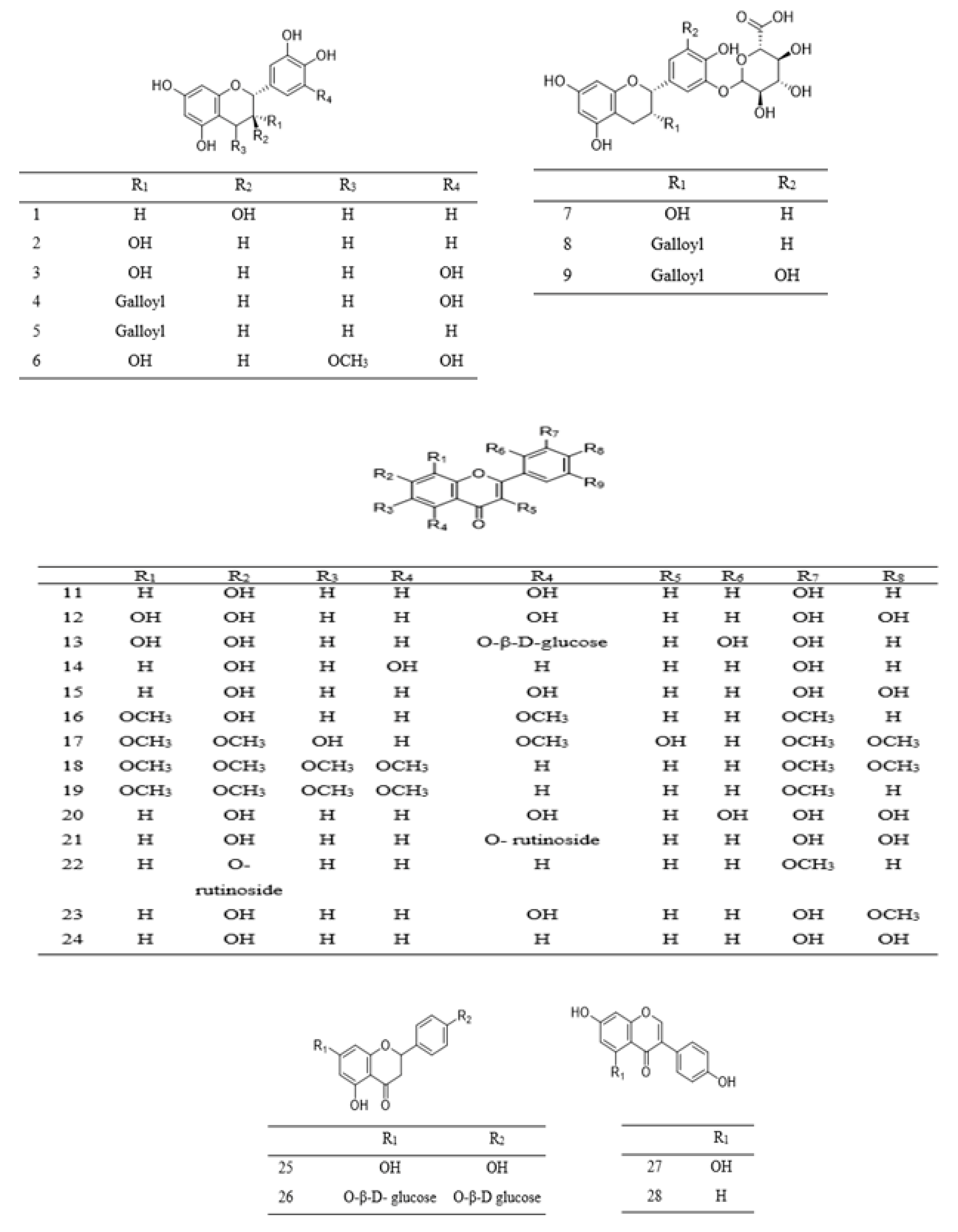

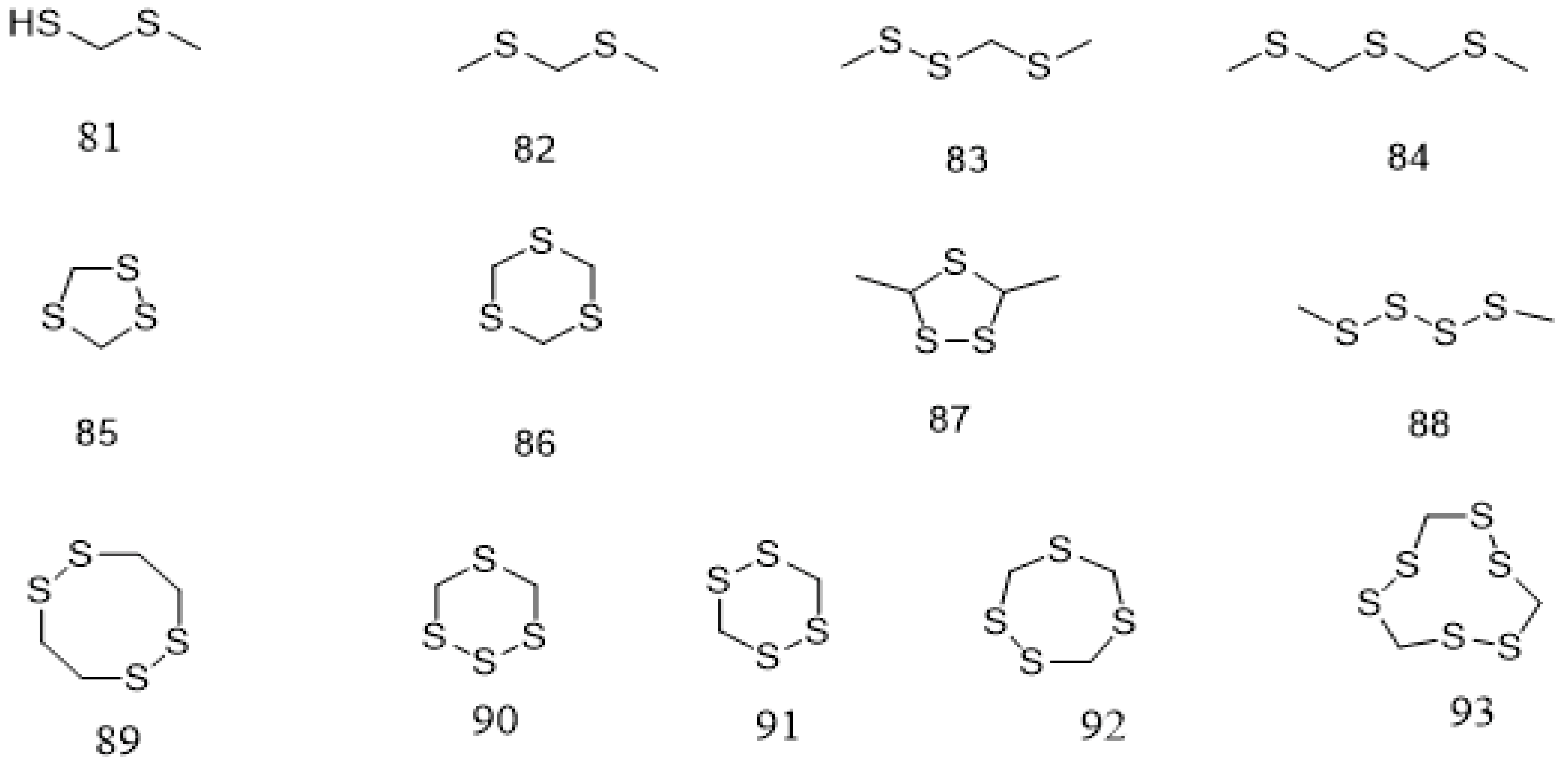

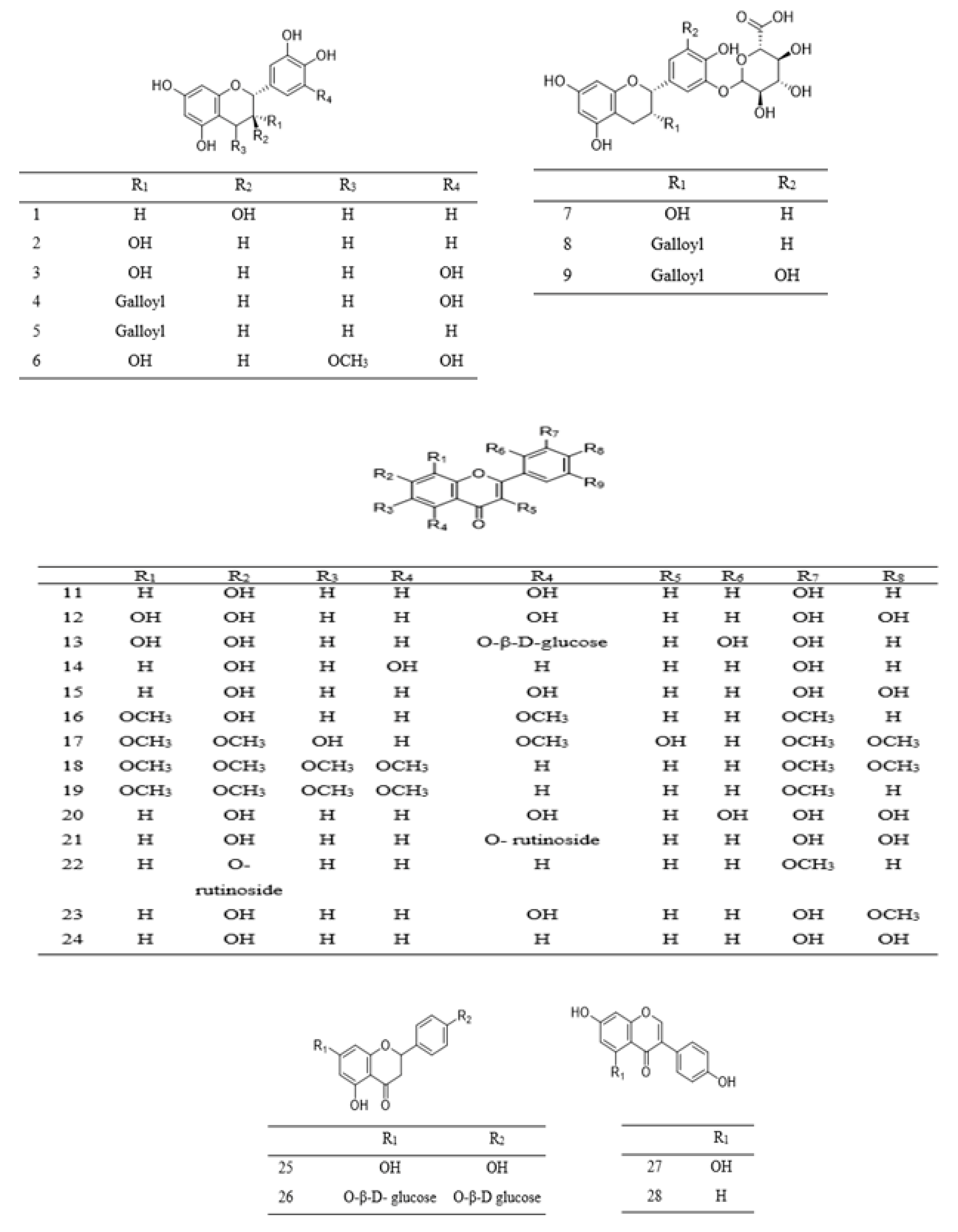

Phenolic compounds found in Parkia species are grouped into simple phenol (10 and 31), phenolic acids 29–41, flavone 15–19 and 24, flavanone 25–26, flavonol 11–14 and 20–22, methoxyflavonol 23, as well as flavanol 1–10 (Table 2). Phenolic acids are mostly found in the pods and edible parts of Parkia, while polyphenolic compounds are present in the leaves, stem barks, roots, or seeds. The most commonly reported flavonoid in Parkia species are flavanol 1 and its isomer 8, which are obtained from the pod and bark of P. speciosa and P. biglobosa, respectively [106,107,108][106][107][108] and the remaining flavanols 11–18 are mainly galloylated catechins. Compound 11 is isolated from ethyl acetate fraction of P. roxburghii pod [18], while compounds 12–18 are identified from the ethyl acetate fraction of root/stem of P. biglobosa [18]. One methoxyflavonol 23, two flavanone 26–27 and isoflavones 27–28 are identified in the edible parts of P. javanica [108]. A new flavanone, naringenin-1-4′-di-O-ß-D-glucopyranoside 26 is isolated from n–butanol fraction of P. biglobosa [109], while a new phenylpropanoid is elucidated as 4-(3-hydroxypropyl)benzyl nonanoate from the leaves of P. javanica [110]. Isolation of compounds 42–43 for the first time as a pure compound was reported from the ethanol extract of P. biglobosa bark [111]. The structures of these compounds are illustrated in Figure 21 and Figure 32.

Figure 21.

Structural formulas of polyphenolics

1

–

28

, as previously listed in

Table 2

.

Figure 32.

Structural formulas of polyphenolics

29

–

46

, as previously listed in

Table 2

.

Table 2.

Phytochemical compounds from

Parkia

.

| Structure Number | Type | Compound | Species | Part | Reference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenolics | |||||||||||

| 1 | Flavanol | Catechin | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | Root/bark | [106] | |||||||||

| P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | |||||||||

| 2 | Flavanol | Epicatechin | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] | ||||||

| P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | |||||||||

| 3 | Flavanol | Epigallocatechin | P. biglobosa | Root/bark | [111] | ||||||

| P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | |||||||||

| 4 | Flavanol | Epigallocatechin gallate | P. roxburghii | Pod | [18] | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | Root/bark | [106,[106111]][111] | |||||||||

| 5 | Flavanol | Epicatechin-3-O-gallate | P. biglobosa | Bark | [111] | ||||||

| 6 | Flavanol | 4-O-methyl-epigallocate-chin | P. biglobosa | Bark | [111] | ||||||

| 7 | Flavanol | Epigallocatechin-O-glucuronide | P. biglobosa | Root/bark | [106] | ||||||

| 8 | Flavanol | Epicatechin-O-gallate-O-glucuronide | P. biglobosa | Root/bark | [106] | ||||||

| 9 | Flavanol | Epigallocatechin-O-gallate-O-glucuronide | P. biglobosa | Root/bark | [106] | ||||||

| 10 | Flavanol | Theaflavin gallate | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] | ||||||

| 11 | Flavonol | Kaempferol | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] | ||||||

| P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | |||||||||

| 12 | Flavonol | Quercetin | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] | ||||||

| 13 | Flavonol | Hyperin | P. roxburghii | Pod | [18] | ||||||

| 14 | Flavonol | Apigenin | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] | ||||||

| 15 | Flavone | 3,7,3′,4′-Tetrahydroxyflavone | P. clappertoniana | Seeds | [113,114][113][114] | ||||||

| 16 | Flavone | 7-Hydroxy-3, 8, 4′-trimethoxyflavone | P. clappertoniana | Leaves | [115] | ||||||

| 17 | Flavone | 2′-Hydroxy-3,7,8,4′,5′′pentamethoxyflavone | P. clappertoniana | Leaves | [115] | ||||||

| 18 | Flavone | Nobiletin | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] | ||||||

| 19 | Flavone | Tangeritin | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] | ||||||

| 20 | Flavonol | Myricetin | P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | ||||||

| P. speciosa | Pod | [112] | |||||||||

| 21 | Flavonol glycoside | Rutin | P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | ||||||

| P. speciosa | Pod | [112] | |||||||||

| 22 | Flavonol glycoside | Didymin | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] | ||||||

| 23 | Methoxy flavonol | Isorhamnetin | P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | ||||||

| 24 | Flavone | Luteolin | P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | ||||||

| 25 | Flavanone | Naringenin | P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | ||||||

| 26 | Flavanone | Naringenin-1-4′-di-O-ß-d-glucopyranoside | P. biglobosa | Fruit pulp | [109] | ||||||

| 27 | Isoflavone | Genistein | P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | ||||||

| 28 | Isoflavone | Daidzein | P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | ||||||

| 29 | Phenolic acid | Gallic acid | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] | ||||||

| P. bicolor | Root | [28] | |||||||||

| 30 | Phenolic acid | Methyl gallate | P. bicolor | Root | [28] | ||||||

| 31 | Phenolic acid | Hydroxybenzoic acid | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] | ||||||

| 32 | Phenolic acid | Vanillic acid | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] | ||||||

| 33 | Phenolic acid | Chlorogenic acid | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | fermented seeds | Aqueous | Lower blood pressure, blood glucose, and heart rate, high level of magnesium as well as improved lipid profile in patients with hypertension | [178][159] | P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | ||||

| Antidiarrheal | P. biglobosa | Stem bark | Aqueous and fractions | The extract of stem bark exhibit dose-dependent antidiarrheal activity at different concentrations in albino rats with castor oil-induced diarrhea | [45][91] | 34 | Phenolic acid | ||||

| P. biglobosa | Ellagic acid | Leaves and stem bark | P. speciosa | Aqueous and ethanolPod | Reduced frequency of stooling in castor-oil induced diarrhea in rats | [193[107] | |||||

| ] | [ | 160 | ] | 35 | Phenolic acid | Punicalin | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] | ||

| P. biglobosa | Stem-bark | 70% Methanol | The extract exhibited 100% protections at 100 and 200 mg/kg bw in the diarrheal rats | [59][35] | 36 | ||||||

| P. filicoidea | Phenolic acid | Stem bark | Caffeic acid | AqueousP. speciosa | Reduced frequency of stooling and improved transit time at 100 and 200 mg/kg bwPod | [192][161[107] | |||||

| ] | P. javanica | Edible part | |||||||||

| Antiulcer | [ | 108 | P. speciosa] | ||||||||

| Leaves | Ethanol | Reduced mucosal injury and increased in periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining induced by ethanol | [ | 198 | ][162] | 37 | Phenolic acid | Cinnamic acid | P. speciosa | Pod | [107] |

| P. speciosa | Seed | Ethanol | Decreased gastric juice acidity, lesion length, collagen content and fibrosis in indomethacin-induced peptic ulcer in rats | [197][163] | 38 | Phenolic acid | P-Coumaric acid | P. speciosa | Pod | [ | |

| P. platycephala | Leaves | 107 | ] | ||||||||

| Ethanol | Reduced gastric mucosal lesion induced by ethanol, ischemia-reperfusion and ethanol-HCl | [ | 199 | ][164] | P. javanica | Edible part | |||||

| Antianemic | [ | 108 | P. biglobosa] | ||||||||

| Combination of fermented seed with other fermented products | Aqueous | Increased hemoglobin, red blood cell, white blood cell levels and packed cell volume in albino rats | [ | 204 | ][165] | 39 | Phenolic acid | Ferulic acid | P. speciosa | ||

| P. biglobosa | Seeds | Ethanol | Increased hemoglobin levels in NaNO2 | Pod | -induced anemic mice | [205][166][107] | |||||

| P. javanica | Edible part | [108] | |||||||||

| P. speciosa | Seeds | Ethanol | Increased hemoglobin levels in NaNO2-induced anemic mice | [205][166] | 40 | Phenolic acid | Coutaric acid | P. speciosa | Pod | [ | |

| Antiangiogenic | P.biglandulosa | 112 | ] | ||||||||

| Fruit and β-sitosterol | Ethanol | The extract and the isolated compound showed antiangiogenic activity on the caudal fin of adult zebrafish | [ | 175 | ][167] | 41 | Phenolic acid | Caftaric acid | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] |

| P. speciosa | Pods | Methanol and water sub-extract | Inhibited more than 50% micro vessel outgrowth in rat aortae and HUVECs | [170][152] | 42 | Phenolic | 1-(w-Feruloyllignoceryl) -glycerol | P. biglobosa | Bark | ||

| Antimalarial | P. biglobosa | Stem bark | [ | 111 | Methanol and fractions] | ||||||

| Showed antiplasmodial activity caused by | P. berghei | and | P. falciparum | [ | 11] | 43 | Phenolic | 1-(w-Isoferuloylalkanoyl) -glycerol | P. biglobosa | Bark | [111] |

| Nephroprotective | P. clappertoniana | Seed | Aqueous | Reduced serum creatinine, Na, urine proteins and leukocytes and kidney weight in gentamicin-induced renal damage in rats | [75][53] | 44 | Phenolic | Malvidin | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] |

| Hepatoprotective | P. biglobosa | Stem barks | Methanol | Reduced serum alanine and aspartate transaminases, and alkaline phosphatase in paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity rat model | [216][168] | 45 | Phenolic | Primulin | P. speciosa | Pod | [112] |

| Wound healing | P. pendula | Seeds | Lectin | Increased skin wound repair in immunosuppressed mice | [217][169] | 46 | Pheny propanoid | Parkinol | P. javanica | Leaves | [110] |

| Anti-inflammatory | P. speciosa | Pods | Ethyl acetate fraction | Reduced iNOS activity, COX-2, VCAM-1 and NF-κB expressions in cardiomyocytes exposed to tumor necrosis factor-α | [229][170] | 47 | Phenol | 2-Methoxy phenol | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] |

| P. speciosa | Pods | Ethyl acetate fraction | Reduced iNOS activity, COX-2, VCAM-1 and NF-κB expressions in HUVECs exposed to tumor necrosis factor-α | [230][171] | 48 | Phenol | 2,4-Disiopropyl-phenol | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | |

| P. biglobosa | Stalk | Methanol | Inhibited croton pellet granuloma formation and carrageenin-induced rat paw edema | [ | Terpenoid and steroid | ||||||

| 206 | ] | [ | 172 | ] | 49 | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | Seeds | Lectin | Lectin showed anti-inflammatory effect by inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine release and stimulation of anti-inflammatory cytokine release on peritonitis induced model mice | [208][173] | Triterpenoid | Lupeol | P. biglobosa | Bark | [111] | ||

| P. biglobosa | Stem bark | Hexane | Reduced carrageenan- and PMA-induced edema in mice | [29] | P. bicolor | Root | [28] | ||||

| P. biglobosa | Fruit | 70% Methanol | Increased percentage protection of the human red blood cell membrane | [209][174] | P. speciosa | Seeds | [117] | ||||

| P. platycephala | Seeds | Lectin | Lectin showed antinociceptive effect in the mouse model of acetic acid-induced | [207][175] | 50 | Monoterpenoid | Limonene | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | |

| Antioxidant | P. javanica | Leaves | Hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol | Methanol extract showed the highest antioxidant potential activities (DPPH test) of about 85% and (FRAP test) of about 0.9 mM Fe (II)/g dry | [231][176] | 51 | Triterpenoid | Ursolic acid | P. javanica | Leaf/stem | [ |

| P. javanica | Leaves | 42 | ] | [ | 88] | ||||||

| Aqueous, ethanol and methanol | All the extracts exhibited good antioxidant activity. The aqueous extract showed the highest values of 47.42 and 26.6 mg of ascorbic acid equivalent/g in DPPH and FRAP tests, respectively | [ | 232 | ][177] | 52 | Triterpenoid | Parkibicoloroside A | P. bicolor | Root | [118] | |

| P. javanica | Pods | Methanol and acetone | High content of total phenolic and flavonoid. Showed high reducing power and strong radical scavenging activity. | [212][178] | 53 | Triterpenoid | Parkibicoloroside B | P. bicolor | Root | [118] | |

| P. javanica | Fruit | Methanol | Showed increased DPPH and ferric-reducing power activities concentration-dependently | [210][179] | 54 | Triterpenoid | Parkibicoloroside C | P. bicolor | Root | [118] | |

| P. speciosa | Pod | Methanol | Increased DPPH scavenging activity | [233][180] | 55 | Triterpenoid | Parkibicoloroside D | P. bicolor | Root | [118] | |

| P. speciosa | Pod | Ethyl acetate fraction | Reduced NOX4, SOD1, p38 MAPK protein expressions and ROS level | [230][171] | 56 | Triterpenoid | Parkibicoloroside E | P. bicolor | Root | [118] | |

| P. speciosa | Pod | Aqueous and ethanolic | Increased DPPH and ABTS scavenging activities, reduced lipid peroxidation Activity: ethanol > aqueous | [107] | 57 | Monoterpenoidal glucoside | 8-O-p-Hydroxl-6′-O-p-coumaryl-missaeno-sidic acid | P. javanica | Leaf | [42] | |

| P. speciosa | Seeds | Ethanol | Extract exhibited significant activity (DPPH and FRAP tests) | [213][181] | [88] | ||||||

| 58 | |||||||||||

| P. speciosa | Monoterpenoidal glucoside | Seed coats and pods7-O-E-3,4-Dimethoxycinnamoyl-6′-O-ß-d-glucopyranosylloganic acid | P. javanica | Leaf | [42][88 | Ethanol | Reduced Heinz body formation in erythrocytes incubated with acetyl phenylhydrazine. Activity: seed coat > pods >] |

||||

| [ | 215 | ] | [ | 182] | 59 | Diterpene | 16-O-Methyl-cass-13(15) ene-16,18-dionic acid | P. bicolor | Root | [118] | |

| P. speciosa | Pods | Ethanol | Increased DPPH scavenging activity | [234][183] | 60 | Steroid | β-Sitosterol | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119,120][117][119][120] | |

| P. biglobosa | Fermented and unfermented seed | Aqueous | Fermented seed increased reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+. | [211][184] | P. javanica | Leaf/stem | [42][88 | ||||

| P. biglobosa | Stem bark | ] | |||||||||

| Aqueous-methanolic | Mitigated ferric-induced lipid peroxidation in rat tissues and increased scavenging activities against DPPH and ABTS, ferric-reducing ability | [ | 235 | ][185] | P. biglobosa | Seed oil | [ | ||||

| P. biglobosa | 121 | ,122][121 | Fruit][122] | ||||||||

| Methanol and hydro-ethanol | Increased DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power. | [ | 210 | ][179] | 61 | Steroid | Stigmasterol | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119 | |

| P. biglobosa | Fruit | Hydroethanolic and methanol | , | 120 | ][117][119][120] | ||||||

| Increased scavenging activity against DPPH free radical | Activity: methanol > hydroethanolic | [ | 210][179] | P. biglobosa | Seed oil | [121,122][121][122] | |||||

| 62 | Steroid | Stigmasterol methyl ester | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119][117][119] | ||||||

| 63 | Steroid | Stigmast-4-en-3-one | P. speciosa | Seed | [123] | ||||||

| 64 | Steroid | Stigmasta-5,24(28)-diene-3-ol | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 65 | Steroid | Campesterol | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119][117][119] | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | Seed oil | [121,122][121][122] | |||||||||

| 66 | Steroid | Stigmastan-6,22-diien,3,6-dedihydo- | P. speciosa | Seed | [119] | ||||||

| Miscellaneous Compounds | |||||||||||

| 67 | Fatty acid | Arachidonic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119][117][119] | ||||||

| P. bicolor | Seed | [22] | |||||||||

| P. biglobosa | Seed | [22] | |||||||||

| 68 | Fatty acid | Linoleic acid chloride | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119][117][119] | ||||||

| 69 | Fatty acid | Linoleic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119][117][119] | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | Seed | [22] | |||||||||

| P. bicolor | Seed | [22] | |||||||||

| 70 | Fatty acid | Squalene | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119][117][119] | ||||||

| 71 | Fatty acid | Lauric acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

| 72 | Fatty acid | Stearic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119,124][117][119][124] | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | Seed | [22] | |||||||||

| P. bicolor | Seed | [22] | |||||||||

| 73 | Fatty acid | Stearoic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 74 | Fatty acid | Eicosanic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 75 | Fatty acid | Oleic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119,124][117][119][124] | ||||||

| 76 | Fatty acid | Palmitic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119,124][117][119][124] | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | Seed | [22] | |||||||||

| P. bicolor | Seed | [22] | |||||||||

| 77 | Fatty acid | Myristic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,119,124][117][119][124] | ||||||

| 78 | Fatty acid | Undecanoic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [119,124][119][124] | ||||||

| 79 | Fatty acid | Stearolic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [119] | ||||||

| 80 | Fatty acid | Hydnocarpic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 81 | Cyclic polysulfide | 1,3-dithiabutane | P. speciosa | Seed | [125] | ||||||

| 82 | Cyclic polysulfide | 2,4- Dithiapentane | P. speciosa | Seed | [125] | ||||||

| 83 | Cyclic polysulfide | 2,3,5-Trithiahexane | P. speciosa | Seed | [125] | ||||||

| 84 | Cyclic polysulfide | 2,4,6-Trithiaheptane | P. speciosa | Seed | [125] | ||||||

| 85 | Cyclic polysulfide | 1,2,4-Trithiolane | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116,126][116][126] | ||||||

| P. speciosa | Seed | [126,127,128][126][127][128] | |||||||||

| 86 | Cyclic polysulfide | 1,3,5-Trithiane | P. speciosa | Seed | [128] | ||||||

| 87 | Cyclic polysulfide | 3,5-Dimethyl-1,2,4-trithiolane | P. speciosa | Seed | [128] | ||||||

| 88 | Cyclic polysulfide | Dimethyl tetrasulfid | P. speciosa | Seed | [128] | ||||||

| 89 | Cyclic polysulfide | 1,2,5,6-Tetrathio-cane | P. speciosa | Seed | [128] | ||||||

| 90 | Cyclic polysulfide | 1,2,3,5-Tetrathiane | P. speciosa | Seed | [128] | ||||||

| 91 | Cyclic polysulfide | 1,2,4,5-Tetrathiane | P. speciosa | Seed | [128] | ||||||

| 92 | Cyclic polysulfide | 1,2,4,6-Tetrathie-pane | P. speciosa | Seed | [126,128][126][128] | ||||||

| 93 | Cyclic polysulfide | 1,2,4,5,7,8- Hexathiolnane |

P. speciosa | Seed | [126] | ||||||

| 94 | Cyclic poly-sulfide | Lenthionine | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124,126,128][117][124][126][128] | ||||||

| 95 | Esters | n-Tetradecyl acetate | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 96 | Esters | Methyl linoleate | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 97 | Esters | Ethyl linoleate | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

| P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | |||||||||

| 98 | Ester | Butyl palmitate | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 99 | Esters | Ethyl palmitate | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 100 | Esters | Methyl palmitate | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 101 | Esters | Methyl laurate | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 102 | Esters | Dodecyl acrylate | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 103 | Esters | Methyl hexadecanoate | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| 104 | Ester | Ethyl stearate | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

| 105 | Ester | Methyl octadecanoate | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| 106 | Ester | Butyl stearate | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 107 | Ester | Propanoic acid, 3,3′-thiobis-didodecyl ester | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 108 | Ester | Linoleaidic acid methyl ester | P. speciosa | Seed | [119] | ||||||

| 109 | Alcohol | 2,6,10,14-Hexadecatetraen-1-ol | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 110 | Alcohol | 1-Octen-3-ol | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| 111 | Alcohol | 3-Ethyl-4-nonanol | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 112 | Alcohol | 1-Tridecanol | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

| 113 | Acid | Eicosanoic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 114 | Acid | 16-O-Methyl-cass-13(15)ene-16,18-dionic acid | P. bicolor | Root | [118] | ||||||

| 115 | Acid | Elaidic acid | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

| 116 | Pyrazine | 2,5-Dimethyl pyrazine | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| 117 | Pyrazine | Trimethyl pyrazine | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| 118 | Pyrazine | 2-Ethyl-3,5-dimethyl pyrazine | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| 119 | Ketone | 2-Nonade-canone | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

| 120 | Ketone | 2-Pyrrolidi-none | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 121 | Ketone | Cyclodecanone | P. speciosa | Seed | [124] | ||||||

| 122 | Alkane | Cyclododecane | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| 123 | Alkane | Tetradecane | P. speciosa | Seed | [119] | ||||||

| 124 | Benzene glucoside | 3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl-1-O-ß-d-glucopy-ranoside | P. bicolor | Root | [118] | ||||||

| 125 | Aldehyde | 2-Decenal | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 126 | Aldehyde | Cyclo-decanone-2,4-decadienal | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 127 | Aldehyde | Pentanal | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| P. speciosa | Seed | [125] | |||||||||

| 128 | Aldehyde | 3-Methylthio-propanal | P. biglobosa | Seed | [116] | ||||||

| 129 | Aldehyde | Tetradecanal | P. speciosa | Seed | [119,124][119][124] | ||||||

| 130 | Aldehyde | Pentadecanal | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

| 131 | Aldehyde | Hexadecanal | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

| 132 | Amine | Hexanamide | P. speciosa | Seed | [117] | ||||||

| 133 | Oil | Vitamin E | P. speciosa | Seed | [117,124][117][124] | ||||||

3.2. Terpenoid and Steroid

To date, few terpenoid compounds have been reported in Parkia plants. Most of these compounds were identified from barks, roots, leaves, and seeds of Parkia plants. One is monoterpenoid 50 with two of its glucosides 57 and 58, a diterpene 49, while the rest are triterpenoid 49 and 51–56 (Table 2 and Figure 43). Seven out of the triterpenoids 52–58 were reported as new compounds. Only 49 is reported in three species (P. biglobosa, P. bicolor, and P. speciosa). Two of the new compounds 57 and 58 are iridoid type of terpenoidal glycoside purified from methanol extract of P. javanica, together with ursolic acid and other steroidal compounds [42][88]. Compounds 52–56 are isolated through different chromatographic techniques from 80% methanol extract of P. bicolor root, with a known diterpene 59 and a benzene glucoside 105. These compounds are reported to exhibit moderate antiproliferative activity with median inhibitory concentration (IC50) ranging from 48.89 ± 0.16 to 81.66 ± 0.17 µM [118].

Figure 43.

Structural formulas of terpenoids

49

–

59

and steroids

60

–

66

, as previously listed in

Table 2

.

3.3. Miscellaneous Compounds

In addition to polyphenolic and terpenoids, several other compounds that are mainly volatile including aldehydes, esters, pyrazines, ketones, fatty acids, benzenes, alcohols, amines, sulfides, alkanes, and alkenes have been reported from Parkia species (Table 2). These compounds are identified mainly from the seeds. Compound 81 is identified from the natural product for the first time in pentane/dichloromethane fraction of P. speciosa seed using GC/ToF-MS [125]. A greater number of these compounds is identified through phytochemical quantification using different spectroscopic methods. Seven constituents are detected from the fresh seeds of P. speciosa through GC/ToF/MS and the compounds are dominated by linear polysulfide, alcohol, and 3′-thiobis-didodecyl ester. Other major compounds include palmitic acid, arachidonic acid, linoleic acid, linoleic acid chloride, and myristic acid [124]. However, cyclic polysulfides are the major constituents found in cooked P. speciosa seeds (Figure 54) [Abbreviations: HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; DPPH, 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazy; ABTS, 2,20-Azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) diammonium salt; FRAP, ferric reducing antioxidant power; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion moelcule-1; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-B; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; HEL, human embryo lung; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff; bw, body weight.

4.1. Antimicrobial Activity

Various parts of many species of Parkia have good antimicrobial activities. They are most active against S. aureus and E. coli (Table 3). So far, there is still no clinical study conducted on the plants investigating the activity. Enormous reports have been made on antimicrobial activity of different parts of P. biglobosa such as leaves [23[23][42][131][186][187][188][189],65,131,132,133,134,135], stem barks [31,43,45,65,67,131,134,135[42][45][79][89][91][186][188][189][190][191],136,137], seeds [138][192], roots [34,38,139][44][82][193] and pods [133,140][131][194]. Furthermore, the stem barks and leaves of P. clappertoniana aqueous and methanol extracts investigated on some Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria revealed that both stem barks and leaves were effective in all tested organisms, but methanol extract was more potent [71][49]. The ethanol extract of both leaves and barks demonstrated growth inhibitory effects on multi-drug resistant Salmonella and Shigella isolates [73][51]. The ethanol extract of P. platycephala seeds tested against six bacteria strains and three yeasts showed no antimicrobial activity [141][195]. However, lectin obtained from the seed was reported to significantly enhance antibiotic activity of gentamicin against S. aureus and E. coli multi-resistant strains due to interaction between carbohydrate-binding site of the lectin and the antibiotic [142][196]. In P. speciosa, the water suspension of the seeds displays some remarkable inhibitory activity against bacteria isolated from the moribund fishes and shrimps—S. aureus, A. hydrophila, S. agalactiae, S. anginosus and V. parahaemolyticus—but no detectable activity against E. coli, V. alginolyticus, E. tarda, C. freundii, and V. vulnificus [143][132]. The methanol, chloroform, and petroleum ether extracts of the seeds demonstrate growth inhibitory effect against H. pylori [144][137], while the ethyl acetate extract against E. coli, but no effect on S. typhi, S. sonnei, and S. typhimurium [144][137]. The antimicrobial activity of P. speciosa is attributable to the presence of cyclic polysulfides 85 and 92–94 in the seeds [126]. However, possible mechanism of the polysulfides was not elucidated. Both pod extract and its synthesized silver nanoparticles exhibit antibacterial activity, with the latter shows higher activity against P. aeruginosa [145][134]. A similar antibacterial activity is also seen with aqueous extract of P. speciosa leaves and its silver nanoparticles against S. aureus, B. subtilis, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa [146][197]. Its bark methanol extract inhibits the growth of Gloeophyllum trabeum, but not Pycnoporus sanguineus, which effect is not seen with both sapwood and heartwood of the plant [147][135]. Its ethyl acetate extract of the peel also shows four times higher activity against S. aureus and three times higher against E. coli than streptomycin, but n-hexane extract exhibits lower activity [148][133]. Various parts of P. timoriana inhibit growth of B. cereus, V. cholerae, E. coli, and S. aureus [149][198]. Its leaf extract exhibits significant growth inhibitory effect against E. coli, V. cholerae, S. aureus, and B. cereus [150][199], while its gold and silver nanoparticles from dried leaves inhibit S. aureus growth. The activity is believed to be attributable to the accumulation and absorption of the gold and silver nanoparticles into S. aureus cell wall [151][140]. The methanol extract and semi-polar fractions (chloroform and ethyl acetate) of the bark demonstrate significant inhibitory effects against Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The chloroform extract shows the best activity [97][76]. The aqueous extract of the seed, leaf and skin pod also possess antimicrobial activity [152][141]. Acetone, ethanol and aqueous extracts of P. biglandulosa stem bark were among the plant extracts that show the highest antimicrobial activity against bacteria and fungi [69][47] as well as plant pathogenic bacteria [153][200]. The methanol extract of the leaves also shows remarkable growth inhibition against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus [154][142]. Investigation on P. bicolor indicates that ethyl acetate, ethanol, and aqueous extracts of the leaves demonstrate a concentration-dependent growth inhibitory effect against some Gram-positive of bacteria such as E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, A. niger, B. cereus, and a fungus, C. utilis [23]. Methanol, ethyl acetate, and water extracts of the root also exhibit different degrees of inhibition against some common human pathogenic bacteria including C. diphtheriae, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, S. typhi, and S. pyogenes [28]. The possible mechanism of the antimicrobial activity of Parkia plants are yet to be determined. However, terpenoids from the plants could induce lipid flippase activity in the bacterial cellular membrane which then enhances membrane damage for a better cell penetration [155][201]. Other possible actions could be by damaging bacterial protein, inhibiting DNA gyrase and DNA synthesis, which are yet to be confirmed in further studies. Collectively, it can be concluded that the antimicrobial properties of Parkia plants depend on the species and parts of Parkia as well as solvent (polar and non-polar). Most of the published report are in in vitro evaluations, which do not assure the same outcomes in animal models and clinical setting. In the rise of resistant pathogenic bacteria to antimicrobial therapy, it is an urgent need to develop new antimicrobial agents, and phytoconstituents from plants like Parkia could be good candidates.4.2. Antidiabetic Activity

P. speciosa is the most studied among other species for antidiabetic activity. Six studies comprising three in vitro and three in vivo studies have demonstrated hypoglycemic activity of the plant, but no clinical study has been conducted. Most of the studies have studied the activity in the seeds and pods [120,156,157,158][120][144][145][202]. Pericarps from P. speciosa show significant inhibitory activity (IC50 0.0581 mg/mL; 89.46%) against α-glucosidase [156][202], an enzyme responsible for breaking down starch and polysaccharide into glucose [159][203]. The seeds also show inhibitory activity but at lower percentage (45.72%) [156][202]. In another study, the ethanol extract of the rind had the highest α-glucosidase inhibitory activity followed by the leaf and seed with IC50 of 4596 ppm, 54,341 ppm, and 67,425 ppm, respectively as compared with acarbose having 162,508 ppm [158][145]. An in vivo study conducted on both seeds and pods of P. speciosa in alloxan-induced diabetic rats, indicated that only chloroform extract of both pods and seeds exhibited strong glucose-lowering activity. The hypoglycemic activity of the seeds was higher than that of the pods (57% and 36%, respectively) [157][144]. A mixture of 66% β-sitosterol 60 and 34% stigmasterol 61 is believed to be responsible for the hypoglycemic effect of the seeds—demonstrated 83% decrease in blood glucose level (100 mg/kg body weight) compared to glibenclamide (111% at 5 mg/kg bw) [120]. Similarly, stigmast-4-en-3-one 63 was identified as the compound responsible for the 84% reduction in blood glucose level at 100 mg/kg bw of the pod extract of P. speciosa [123]. Both compounds (β-sitosterol and stigmasterol) are believed to reduce blood glucose level by regenerating remnant β-cells and stimulating insulin release [160][146] via augmentation of GLUT4 glucose transporter expression [161][147]. Stigmasterol is also reported to inhibit the ß-cells apoptosis [162][204]. In other Parkia species, methanol crude extracts and fractions of P. timoriana pods showed significant α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory activities in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Ethyl acetate fraction had the highest α-glucosidase inhibitory and moderate α-amylase inhibitory activities, with maximal reduction in blood glucose level back to normal observed on day 14 at the dose of 100 mg/kg body weight [18]. α-Amylase functions to hydrolyze starch into maltose and glucose [163][205]. Bioassay-guided chemical investigation of the most active ethyl acetate fraction revealed epigallocatechin gallate 4 and apigenin 14 were responsible for the antidiabetic activity [18]. Oral administration of P. biglobosa methanol and aqueous extracts of fermented seeds exhibited different degrees of hypoglycemic effects on fasting plasma glucose when tested on alloxan-induced diabetic rats after four weeks [164,165][206][207]. Oral administration of P. biglobosa seeds methanol extract (1 g/kg body weight) lowered blood glucose level by 44.1% at 8 h as compared with glibenclamide (37.9%) in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Its chloroform fraction exerted maximum glucose-lowering effect (65.7%), while n-hexane fraction had the lowest (4.7%) [39][86]. As previously mentioned, similar underlying mechanism of the hypoglycemic activity of the plant species is suggested which is via an improvement in pancreatic islet functions to release insulin, while abolishing insulin resistance [166][208]. For future study directions, investigations on the effects of the plant extracts and pure compounds on insulin release and signaling pathways that might be involved in the glucose-lowering properties could be conducted. The compounds should also be studied clinically.4.3. Anticancer Activity

Cancer is one of the diseases that cause death of millions worldwide. Dietary intake of raw seeds was also reported to significantly lower the occurrence of esophageal cancer in southern Thailand [167][209]. The methanol extract of P. speciosa seeds exhibited a moderate antimutagenic activity in the Ames test [168][210], but weak activity in Epstein–Barr virus inhibitory assay [169][211]. The methanol extract of the seed coats demonstrated selective cytotoxicity against MCG-7 and T47D (breast cancer), HCT-116 (colon cancer) and HepG2 (hepatocarcinoma) cells, while its ethyl acetate fraction only showed selective cytotoxicity against MCF-7, breast cancer cells [170][152]. Substances that enhance mitogenesis of lymphocytes may be useful as antitumor or antiproliferative and immunomodulator agents [171][212]. Lectin obtained from the P. speciosa seeds exerted mitogenic activity in both rat thymocytes and human lymphocytes by stimulating the incorporation of thymidine into DNA cell, which activity was comparable to the known T-cell mitogens like pokeweed mitogen, concanavalin A and phytohemagglutinin [6,172][6][213]. Lectins isolated from the seeds of P. biglandulosa and P. roxburghii have demonstrated antiproliferative effect on murine macrophage cancer cell lines—P 388DI and J774. The seed extract P. roxburghii also inhibits the proliferation of B-cell hybridoma cell line, HB98 [173][150], and HepG2 cells without affecting the normal cells [44][90]. The monosaccharide saponins 52–55 isolated from P. bicolor root also exhibit moderate antiproliferative effect IC50 ranging from 48.49 to 81.66 µM [118]. To researchers' knowledge, the anticancer effects of Parkia extracts were only investigated in cell lines—limited to cell growth inhibition—not yet studied in in vivo models. An in vitro study on human cancer cell lines has shown that the methanol extracts of P. biglobosa and P. filicoidea exhibit different degrees of antiproliferative activities on T-549 and BT-20 (prostate cancer), PC-3 (acute T cell leukemia Jurka), and SW-480 (colon cancer) at concentrations of 20 and 200 µg/mL. P. biglobosa also exhibits higher cytotoxic activity against all types of cancer cell lines used compared with P. filicoidea [174][153]. The antitumor property could be attributable to the antiangiogenic activity of some species of Parkia such as P. biglandulosa and P. speciosa extracts [170,175][152][167]. Angiogenesis or neovascularization is involved in metastasis of solid tumors. Methanol extract of the P. speciosa fresh pods was reported to exhibit antiangiogenic activity by more than 50% inhibition of microvessel outgrowth in rat aortae and human umbilical vein endothelial cells forming capillary-like structures in Matrigel matrix. The effect may be attributable to the ability of the compounds in the extract to form vacuoles in the cells [170][152], which is essential in maintaining the viability of the cells, therefore beneficial in the treatment of cancer owing to its capacity to prevent tumor neovascularization [176][214]. The plant bioactive compounds could also possibly increase apoptotic signaling pathway by elevating caspase activation as similarly shown by the same compounds in other plant species [177][215], as well as a direct inhibition on DNA synthesis, related to the ability to inhibit the expressions of several tumor- and angiogenesis-associated genes. Future studies should explore on the possible mechanism of action that are responsible for the anticancer activity. Additionally, future research on human studies is needed to confirm the outcomes seen in the laboratories.4.4. Antihypertensive Activity

Antihypertensive activity of P. biglobosa seeds has been demonstrated in both animals and human. Only a clinical study was conducted which observed lower blood pressure, blood glucose and heart rate, high level of magnesium as well as improved lipid profile in patients with hypertension consuming fermented seeds of P. biglobosa in comparison with the non-consumption group [178][159]. Administration of 1.9 mg/mL of seed extract of P. biglobosa lowers the arterial blood pressure level in a rat model, possibly due to its ability to slow down the heart rate [179][216] and to induce vascular relaxation [180][158]. The latter effect is also seen with roasted seeds of the plant [180][158]. Other than the seeds, P. biglobosa stem bark aqueous extract also demonstrates good hypotensive effect in adrenaline-induced hypertensive female rabbits, which effect is comparable to antihypertensive drugs, propranolol and nifedipine [181][157]. The hypotensive properties of P. biglobosa could be owing to its main phytochemicals−phenolics and flavonoids. Catechin and its derivatives are among the most common compounds detected in the plant. These compounds promote vasorelaxation [182][217] by modulating nitric oxide availability [183][218] and inhibiting angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) [184][219], in addition to a reduction in oxidative stress [185][220], leading to blood pressure-lowering effects of the plant extract. The fermented seeds also decrease plasma triglyceride and cholesterol levels in Tyloxapol-induced hyperlipidemic rats [186][221], and platelet aggregation [187][222]. P. speciosa empty pod extract has been reported to prevent the development of hypertension in rats given L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME), a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, possibly due to its ability to prevent nitric oxide loss [122], which is dependent on the availability of endothelial nitric oxide synthase [188][223], as well as to inhibit ACE and oxidative stress and inflammation [112]. Both oxidative stress and inflammation are known to play important roles in the pathogenesis of hypertension (Siti et al. 2015). Active peptide obtained from hydrolyzed P. speciosa seeds displays ACE-inhibitory effect, ranging from 50.6% to 80.2%, which effect is not observed in the non-hydrolyzed seeds, possibly due its long and bulky structure [189,190][155][156]. However, the study of Khalid and Babji (2018) has demonstrated that the aqueous extract of the seeds also possesses ACE inhibitory activity [191][154]. These studies suggest that the blood pressure-lowering effect of the P. speciosa is most likely due to its ACE inhibitory property and nitric oxide regulation, attributable to its rich contents of polyphenols and the presence of peptide. Future studies should involve isolation of the active compounds which have a potential to be developed as a specific inhibitor of ACE. Other possible mechanisms—specific receptor antagonism, such as adrenoceptors and calcium channels, or modification of signaling pathways—of blood pressure-lowering effects of the plant extract or compounds should be explored further.4.5. Antidiarrheal Activity

The antidiarrheal effect of Parkia plants has been investigated using many models such as castor oil- and magnesium-induced diarrhea. The aqueous extract of P. filicoidea stem barks reduces the frequency of stooling in rats with castor oil-induced diarrhea, comparable with loperamide [192][161]. The aqueous and ethanol extract of P. biglobosa leaves and stem barks also exhibit similar antidiarrheal activity to loperamide, seen as a reduction in stooling frequency and intestinal volume [45,59,193][35][91][160]. These effects could be attributable to its inhibitory capacity on the propulsive movement of gastrointestinal tract smooth muscles [45][91]. Medicinal plants are believed to exert antidiarrheal activity by enhancing the opening of intestinal potassium channel and stimulating Na+/K+-ATPase activity, as well as decreasing intracellular calcium concentration, which then promotes gastrointestinal smooth muscle relaxation, leading to diminished diarrhea [194,195,196][224][225][226]. The potential of these plants as agents to reduce diarrhea can be explored further in irritable bowel syndrome or chemotherapy-induced diarrhea. Their effects on intestinal mucosal barrier, tight junction proteins and inflammatory cytokines among others can be examined.4.6. Antiulcer Activity

The gastroprotective effect of Parkia plants was seen in three species which were P. speciosa, P. platycephala and P. biglandulosa (Table 3). The leaves and seeds of P. speciosa protected against ethanol- and indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer in rats, observed by reductions in the gastric ulcer index and acidity of gastric juice [197,198][162][163]. Lesser collagen and fibrotic ulcer were significantly diminished in the extract-treated group [197][163]. The ethanol extract of P. platycephala also showed protective effect in gastric mucosal injury models induced by ethanol, ischemia-reperfusion, and ethanol-HCl. However, the extract could not protect against indomethacin-induced gastric lesion [199][164]. These plants are rich in flavonoids. The compounds like catechin and quercetin confer antiulcer effects possibly by eradicating the formation of ROS and modulating mucin metabolism in the gastrointestinal tract [200,201,202][227][228][229]. Other possible protective mechanisms could be by reducing gastric acid secretion, thereby decreasing gastric acid pH, as seen with cinnamic caffeic, p-coumaric or ferulic acids—the compounds that are present in the plants [203][230]. Studies on other possible effects of the extracts or bioactive components such as proton pump inhibition could be of interest. In future, the compounds that are responsible for the protective effects should be identified and the possible protective signaling mechanisms should be elucidated. Moreover, clinical trials can be performed to assess the potential use of Parkia extracts as an antiulcer agent.4.7. Antianemic Activity

The fermented seeds of P. biglobosa are a rich source of essential minerals such as iron, calcium, thiamine, and phosphorus [57][33] which are necessary in forestalling either iron or non-iron deficiency anemia. Therefore, the antianemic capacity of P. biglobosa could be owing to its nutritional composition. The fermented seeds of P. biglobosa in combination with other fermented products were reported to be beneficial in the management of anemia as it increased hemoglobin, red blood cells, white blood cells, and packed cell volume [204][165]. The ethanol extract of P. speciosa seeds were also investigated in NaNO2-induced anemic mice. At doses of 400 and 700 mg/kg, an elevation of hemoglobin levels was noted to 0.92 and 0.82 g/dL, respectively [205][166]. The exact mechanism of how P. speciosa acts to decrease anemia is still unclear. It could be due to its rich source of the minerals, particularly the iron [171][212]. Another possible mechanism would be stimulation of erythropoiesis process. Both extracts of P. biglobosa P. biglobosa and P. speciosa can be developed as an alternative iron supplement. However, the effectiveness should be evaluated clinically.4.8. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Inflammatory reaction is involved in almost all clinical manifestation. Hence, anti-inflammatory activity of certain plant extracts could be of benefit. Anti-inflammatory activity of P. biglobosa stalk [206][172], seeds and stem bark [29], P. speciosa pods [187,188][222][223] and seeds [84][62], as well as P. platycephala seeds [207][175] have been reported using various models of inflammation. The protective effects of P. biglobosa is believed via its inhibitions on the lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase pathways [206][172], leading to inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine release and stimulation of anti-inflammatory cytokine [208][173], as well as increment on membrane stabilization [209][174]. While the P. speciosa exerts its anti-inflammatory by downregulating nuclear factor kappa B cell (NF-κB) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [187,188][222][223]. It is obvious that the plant bioactive components attenuate inflammation by regulating inflammatory and MAPK signaling pathways, which could lead to reduced formation of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines. To date, no study has identified the anti-inflammatory compounds from Parkia, which warrants further studies on this aspect, either in experimental animals or human studies.4.9. Antioxidant Activity

Polyphenolic compounds present in plant foods have been reported to be responsible for their antioxidant activity due to their ability to serve as a hydrogen donor and reducing agent (Amorati and Valgimigli 2012). Both fermented and unfermented seeds of P. biglobosa have been reported to contain an appreciable amount of phenolic contents [210,211][179][184]. P. timoriana pods are also rich in total phenolic and flavonoid contents [212][178]. The antioxidant capacity of the leaves and seeds of P. speciosa has been reported to be relatively lower than that of the empty pods and seed mixture, suggesting that the pods possess higher antioxidant contents than other parts of the plant [37,176][85][214]. The difference in geographical location may affect the composition of the antioxidant compounds in plants. It was reported that P. speciosa seeds collected from central Peninsular Malaysia had higher antioxidant capacity than the southern and southwestern regions [213][181]. The compounds present in the plants attenuate oxidative stress possibly by activating Nrf2/Keap1 and MAPK signaling pathways, leading to enhanced expressions of Nrf2 and antioxidant enzymes, such as heme oxygenase-1 [214][231]. P. speciosa extracts of seed coats and pods could also reduce the risk of hemolysis by inhibiting Heinz body production in the erythrocytes incubated with a hemolytic agent [215][182], indicating the ability of the extracts to inhibit oxidative destruction of erythrocyte. The finding suggests a potential of the plant extract to reduce hemolytic jaundice, which warrants further research.4.10. Other Pharmacological Activities

Other than previously mentioned activities, the P. biglobosa extract has also been demonstrated to have antimalarial effect [11], whereas P. clappertoniana [75][53] and P. biglobosa [216][168] show nephro- and hepatoprotective effects, respectively (Table 3). P. pendula seeds also enhance wound healing in immunosuppressed mice [217][169]. However, extensive studies regarding these effects were not performed. Further studies need to be conducted to explore the possible mechanisms that are involved in the aforementioned beneficial effects.5. Toxicity

Daily consumption of cooked pods of P. roxburghii does not impose any significant adverse effect [218][232]. However, eating raw pods may result in bad breath owing to its rich content in volatile disulfide compounds, which are exhaled in breath and the odor can persist for several hours (Meyer, 1987). Many substances have been identified or isolated from Parkia seed, such as lectins, non-protein amino acids, and alkaloids [219][233]. However, no acute mortality and observable behavioral change were recorded at doses up to 2000 mg/kg ethyl acetate fraction of P. roxburghii pod in rats [18]. Investigation on acute and sub-acute toxicity profiles of the aqueous and ethanol extracts of the stem bark of P. biglobosa showed that the oral median lethal dose (LD50) was higher than 5000 mg/kg for both extracts in rats [36][84]. However, in another report, LD50 values of the leaves, stems and roots in an acute toxicity study were within the range of 500–5000 mg/kg body weight of fish, suggesting that they are only slightly toxic and, therefore, not potentially dangerous. The adverse effects included respiratory distress and agitated behavior [220][234]. Apart from the barks of P. biglobosa, the pods also possess the piscicidal activity that can be used in the management and control of fishponds to eliminate predators [220,221][234][235]. Fatty acids and oils identified from the seeds of P. biglobosa and P. bicolor were reported to be non-toxic [22]. The aqueous extract of P. clappertoniana seeds showed no observable maternal and developmental toxicity at 100–500 mg/kg when given orally to Sprague-Dawley rats and mice at different gestational age ([17]. P. platycephala leaves at 1000 mg/kg on the other hand, caused decreases in body mass, food and water consumption in rats. It also shortened the proestrus and prolonged diestrus phases, as well as reduced uterine weight, suggestive of possible alterations on hormonal levels, but no obvious toxicity on other organs [53][98]. Oral administration of the leaves of P. speciosa for 14 days showed no significant histopathological toxicity or mortality in rats at up to 5000 mg/kg [198][162]. In vitro, the plant pods (100 μg/mL) showed no significant cytotoxic effect on normal cell lines [170][152]. Consumption of the seeds up to 30 pieces in a serve does not produce any adverse effects [176][214].References

- Heymann, E.W.; Lüttmann, K.; Michalczyk, I.M.; Saboya, P.P.P.; Ziegenhagen, B.; Bialozyt, R. DNA fingerprinting validates seed dispersal curves from observational studies in the neotropical legume Parkia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35480.

- Orwa, C.; Mutua, A.; Kindt, R.; Jamnadass, R.; Simons, A. Agroforestree Database: A Tree Reference and Selection Guide, version 4; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009.

- Luckow, M.; Hopkins, H.C.F. A cladistic analysis of Parkia (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae). Am. J. Bot. 1995, 82, 1300–1320.

- Neill, D.A. Parkia nana (Leguminosae, Mimosoideae), a new species from the sub-Andean sandstone cordilleras of Peru. Novon A J. Bot. Nomencl. 2009, 19, 204–208.

- Ching, L.S.; Mohamed, S. Alpha-tocopherol content in 62 edible tropical plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3101–3105.

- Suvachittanont, W.; Peutpaiboon, A. Lectin from Parkia speciosa seeds. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 4065–4070.

- Ogunyinka, B.I.; Oyinloye, B.E.; Osunsanmi, F.O.; Kappo, A.P.; Opoku, A.R. Comparative study on proximate, functional, mineral, and antinutrient composition of fermented, defatted, and protein isolate of Parkia biglobosa seed. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 139–147.

- Alabi, D.A.; Akinsulire, O.R.; Sanyaolu, M.A. Qualitative determination of chemical and nutritional composition of Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) Benth. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 4, 812–815.

- Fetuga, B.L.; Babatunde, G.M.; Oyenuga, V.A. Protein quality of some unusual protein foodstuffs. Studies on the African locust-bean seed (Parkia filicoidea Welw.). Br. J. Nutr. 1974, 32, 27–36.

- Hassan, L.G.; Umar, K.J. Protein and amino acids composition of African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa). Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2005, 5, 45–50.

- Builders, M.; Alemika, T.; Aguiyi, J. Antimalarial Activity and isolation of phenolic compound from Parkia biglobosa. IOSR J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2014, 9, 78–85.

- Ifesan, B.O.T.; Akintade, A.O.; Gabriel-Ajobiew, R.A.O. Physicochemical and nutritional properties of Mucuna pruriens and Parkia biglobosa subjected to controlled fermentation. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 2177–2184.

- Iheke, E.; Oshodi, A.; Omoboye, A.; Ogunlalu, O. Effect of fermentation on the physicochemical properties and nutritionally valuable minerals of locust bean (Parkia biglobosa). Am. J. Food Technol. 2017, 6, 379–384.

- Abdullahi, I.N.; Chuwang, P.Z.; Anjorin, T.S.; Ikemefuna, H. Determination of Mineral Accumulation through Litter Fall of Parkia Biglobosa Jacq Benth and Vitellaria Paradoxa Lahm Trees in Abuja, Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Res. Agric. Sci. 2015, 2, 0016–0021.

- Singh, N.P.; Gajurel, P.R.; Rethy, P. Ethnomedicinal value of traditional food plants used by the Zeliang tribe of Nagaland. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2015, 14, 298–305.

- Mondal, P.; Bhuyan, N.; Das, S.; Kumar, M.; Borah, S.; Mahato, K. Herbal medicines useful for the treatment of diabetes in north-east India: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2013, 3, 575–589.

- Boye, A.; Boampong, V.A.; Takyi, N.; Martey, O. Assessment of an aqueous seed extract of Parkia clappertoniana on reproductive performance and toxicity in rodents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 185, 155–161.

- Sheikh, Y.; Maibam, B.C.; Talukdar, N.C.; Deka, D.C.; Borah, J.C. In vitro and in vivo anti-diabetic and hepatoprotective effects of edible pods of Parkia roxburghii and quantification of the active constituent by HPLC-PDA. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 191, 21–28.

- Singh, M.K. Potential of underutilized legume tree Parkia timoriana (DC.) Merr. In Eco-restoration of Jhum fallows of Manipur. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 1685–1687.

- Roosita, K.; Kusharto, C.M.; Sekiyama, M.; Fachrurozi, Y.; Ohtsuka, R. Medicinal plants used by the villagers of a Sundanese community in West Java, Indonesia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 115, 72–81.

- Srisawat, T.; Suvarnasingh, A.; Maneenoon, K. Traditional medicinal plants notably used to treat skin disorders nearby Khao Luang mountain hills region, Nakhon si Thammarat, Southern Thailand. J. HerbsSpices Med. Plants 2016, 22, 35–56.

- Aiyelaagbe, O.O.; Ajaiyeoba, E.O.; Ekundayo, O. Studies on the seed oils of Parkia biglobosa and Parkia bicolor. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 1996, 49, 229–233.