Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Ramon Eritja and Version 2 by Sirius Huang.

Antisense and small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides have been recognized as powerful therapeutic compounds for targeting mRNAs and inducing their degradation. However, a major obstacle is that unmodified oligonucleotides are not readily taken up into tissues and are susceptible to degradation by nucleases. For these reasons, the design and preparation of modified DNA/RNA derivatives with better stability and an ability to be produced at large scale with enhanced uptake properties is of vital importance.

- antisense oligonucleotides

- siRNA

- lipid-oligonucleotide conjugates

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, therapeutic oligonucleotides have gained momentum as an approach to drug development; consequently, there has been a large development of the field. Although the first oligonucleotide approved for therapeutic application in humans dates back to 1998 [1], the recognition of their full therapeutic potential started in 2016 with the authorization of Spinraza [2], for the treatment of Spinal muscular dystrophy, and Etiplersen [3], for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. In both cases, the possibility of targeting a mutated gene through alternative splicing became a major success for a long-time dream. Since then, the list of oligonucleotides approved for human practices has reached the dozens, especially with the incorporation of siRNAs in the therapeutic arena [4].

Oligonucleotide therapeutics include antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) [5], small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) [4], aptamers [6], microRNAs [7], and others [8]. ASOs are small single stranded nucleic acids that by complementarity, bind to a particular mRNA and form a hybrid molecule to modulate gene expression. They act through two mechanisms of action (a) by steric blockade at the ribosomes or (b) by recruiting RNase H enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of mRNA [5]. On the other hand, siRNAs consist of 21–23 mer RNA duplex formed by a sense and an antisense strand complementary to mRNA. The latter is responsible for the recruitment of the target transcript into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that leads to gene silencing [4]. Unmodified oligonucleotides are not readily taken up into tissues and are also susceptible to degradation by nucleases. For these reasons, the design and preparation of more stable modified DNA/RNA derivatives to improve the existing limitations, like inefficient delivery and mature to the position of clinical utility, is of key importance. Regarding the nuclease resistance, novel derivatives are being developed [9]. The delivery issue is being addressed by the following approaches: by encapsulation in nanomaterials such as solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) or by preparing novel oligonucleotide conjugates with selective targeting moieties [10]. The first FDA-approved siRNA, Onpattro [11], is the paradigm of the former; N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) oligonucleotide conjugates [12] are the paradigm of the latter. GalNAc oligonucleotide-conjugates have been shown to be delivered to hepatocytes by binding to asyaloglycoprotein receptors [12]. The latest FDA-approved therapeutic siRNAs, including Givosiran [13], Lumasiran [14], Inclisiran [15], Vutrisiran [16], are based on this strategy. Importantly, Inclisiran (Leqvio®) exerts its therapeutic action within a twice-yearly administration regime [17] while most of the therapeutic siRNAs are administered monthly or every two months [13][14][16][13,14,16]. The large duration of the therapeutic effects of Inclisiran is not only due to a combination of the stability achieved by the modifications on the siRNAs and the efficacy in the delivery, but also to the efficient inhibition of the proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) [15][17][15,17].

The success in exploring oligonucleotide conjugates for hepatic delivery has triggered an intense quest for oligonucleotide conjugates with tissue-selective targeting properties, particularly for extrahepatic delivery [18].

2. Early Developments in the Synthesis of Lipid-Oligonucleotide Conjugates

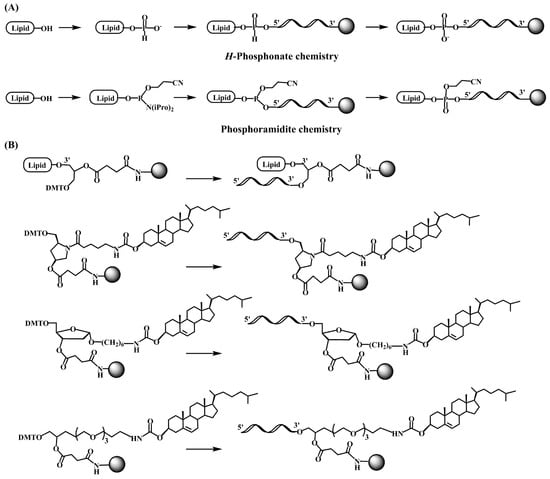

The pioneering works on the antiviral activity of oligonucleotides [19][20][20,21] stimulated the development on lipid-oligonucleotide conjugates as potential candidates for the inhibition of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) in cell culture. Cholesterol was first selected to enhance the interaction between oligonucleotides and cell membranes, which increases the antiviral activity of the oligomers [21][22][22,23]. Letsinger’s group designed a synthetic protocol based on the solid-phase oxidation of H-phosphonate dinucleotide intermediates with amino-functionalized cholesterol and catalyzation by carbon tetrachloride, which generated the desired cholesterol-oligonucleotides bond through a phosphoramidate link (Figure 1A) [21][22] or by direct coupling at the 5′-termini with the H-phosphonate derivative of cholesterol [22][23][23,24]. The H-phosphonate derivative of a diacylglycerol was also used for the incorporation of 1,2-di-O-hexadecyl-rac-glyceryl residue at the 5′-end of antiviral oligonucleotides [24][25]. Solution techniques using amino-lipids [25][26] or thiocholesterol [26][27] were also used for conjugation in order to generate physiologically-labile ester [25][26] or disulfide [26][27][27,28] bonds between the lipid and the oligonucleotide. These groundbreaking studies proved the utility of lipid-oligonucleotides by demonstrating that the lipid moiety enhances nuclease resistance and maintains or improves hybridization properties [24][28][25,29]. However, in some cases, antiviral properties groundbreaking antisense inhibition rules suggest other mechanisms, such as binding to viral and/or cell membranes [21][22][24][22,23,25].

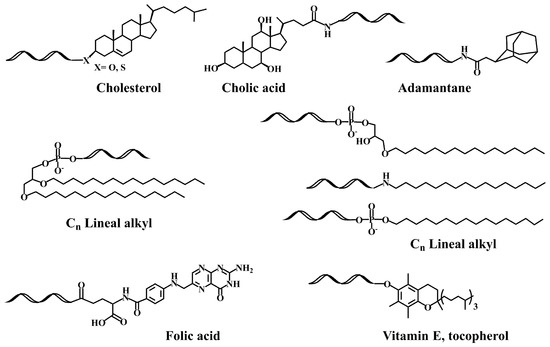

The next step was the development of specific lipid-phosphoramidites and lipid-functionalized solid supports (Figure 1B). Due to the lability of the ester bonds to ammonia [29][30], they were replaced by ether, amide and urethane linkers. Several derivatives carrying ether and glyceryl ether bonds were developed by the group of Tom Brown, including 3′ and 5′-cholesteryl, 5′-(1,2-dihexadecylglyceryl), 3′ and 5′-hexadecyl, 5′-octadecyl and 5′-adamantyl [30][31] as well as vitamin E derivatives (Scheme 1) [31][32]. Other groups worked on new cholesterol derivatives containing aminodiols such as 3-amino-1,2-propanediol [28][29] and 3-aminopropylsolketal [32][33][33,34], in which the cholesterol moiety was linked to the amino group by reaction with cholesterol chloroformate generating an urethane bond stable to ammonia.

On the other hand, postsynthetic conjugation reactions between amino-oligonucleotides and carboxylic acid derivatives of lipids such as cholic acid, adamantane acetic acid and fatty acids were described [34][35][36][35,36,37]. A variation of this protocol implies the addition of 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-protected amino linkers into oligonucleotides. After the assembly of the sequence, the Fmoc moiety can be removed generating a free amino group that reacts with cholesterol chloroformate followed by standard ammonia deprotection [37][38].

The availability of lipid-oligonucleotides allowed its preclinical evaluation demonstrating specific antisense activity, enhanced nuclease resistance and maintenance or improvement of hybridization properties [40][41][41,42]. Another interesting property is its capability to bind to serum proteins and lipoproteins, which is important to avoid renal clearance of oligonucleotides [42][43]. Several specific receptor-mediated uptake mechanisms have been described to explain selective uptake by hepatocytes via lipoprotein receptors [43][44]. Although lipid-oligonucleotide conjugates have interesting properties, none of them, except polyethyleneglycol (PEG) derivatives, have found their way to clinical studies. The synthesis of oligonucleotides functionalized with PEG has been described by the Erdmann and Bonora groups, being somehow similar to the methodology described herein for other lipid diols [44][45][46][47][45,46,47,48]. Pegaptanib (Macugen®) is a therapeutic oligonucleotide used for the treatment of aged-associated macular degeneration. This oligonucleotide is an aptamer constituted by 28 nucleotides and functionalized with PEG at the 5′-end and an inverted-T at the 3′-end to prevent degradation by nucleases [48][49]. This aptamer has a strong affinity to the vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF165 (Kd = 49 pM), inhibiting the binding of VEGF to its receptor, suppressing the VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and consequently lowering vascular permeability and inflammation [49][50].

3. Lipid-Oligonucleotide Conjugates and the Development of RNA-Based Therapeutics

The discovery of the RNA interference mechanisms provided a great resurgence in the area of therapeutic oligonucleotides. Soon after the work of Mello and Fire [50][51], it was established that the effector molecules of the RNA interference process were double stranded RNA molecules of 19–21 nucleotides. Then, synthetic oligonucleotides with chemical modifications were proved to improve the efficacy and the duration compared to natural substrates [51][52][52,53]. Later, the discovery of the microRNAs increased the therapeutic potential of oligonucleotides [53][54]. Cholesterol-siRNAs were developed and were demonstrated to be successful derivatives for the inhibition of lipoproteins [54][55]. Stable nucleic acid lipid nanoparticles (SNALP) and solid-lipid nanoparticles (SLN) were developed for the delivery of siRNAs [55][56][56,57] showing for the first time the in vivo inhibition of ApoB in non-human primates [55][56]. To expand the arsenal of available cationic lipids for siRNAs delivery, several lipids and lipoids libraries were screened, thereby generating lipids with high efficiency and less toxicity [57][58][58,59].

These studies led to the search for new hydrophobic molecules to enhance the cellular uptake of siRNAs [59][60][61][62][60,61,62,63]. Conjugation of amino-siRNAs with a small library of carboxyl-lipids including cholesterol, fatty-acids and bile acids resulted in hydrophobic siRNA derivatives that interact with lipoproteins [43][44]. The obtained hydrophobic (lipo-siRNA-protein) complexes were efficiently delivered to liver, gut and kidney by specific lipoprotein-mediated receptors. Inspired by these results, researchers studied a small lipid library including both neutral [38][39] and cationic lipids [39][40]. The study of TNF-alpha inhibition with and without lipofectamine proved that these lipid-siRNA conjugates carrying ammonia-resistant glycerol ether bonds were compatible with RNA interference mechanisms. A lipid carrying two linear hydrocarbon chains was the best derivative in terms of increasing cellular entrance (Scheme 1) [38][39]. These double-chain lipid-siRNA conjugates stimulated the formation of small vesicles that may explain the improved uptake properties [63][64][64,65]. In addition, a good correlation was found among cell lines expressing abundant CR3 receptors [63][64]. The vesicle formation properties and the enhanced binding of siRNAs carrying double-chain lipids to hydrophobic membranes has also been observed by several authors [65][66][67][66,67,68]. Furthermore, researchers found that the sonication of lipophilic siRNA in presence of serum enhanced the binding of lipophilic-siRNA to lipoproteins, resulting in a more efficient transfection [68][69].

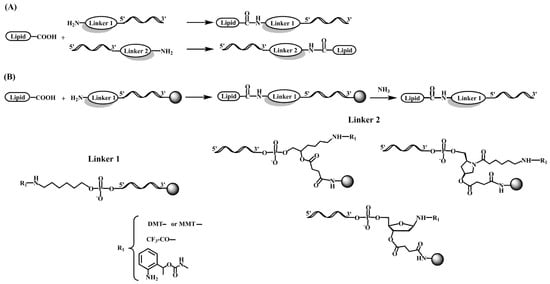

In a different approach, cholesterol-conjugated single-stranded short RNA molecules, or antagomiRs, were successfully used to silence miRNA [69][70][71][72][70,71,72,73]. In addition, G-quadruplex-forming oligonucleotides carrying lipid moieties were found to increase their affinity for viral membrane proteins showing antiviral properties by inhibition of viral cell entry [73][74][75][74,75,76]. The most frequent methodology for the preparation of oligonucleotide-lipid conjugates is based on amide formation (Figure 2), but other reactions such as the copper catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (click chemistry) have also been reported [76][77].

Figure 2. Chemical structure of several linker molecules connecting solid supports and lipids used for the preparation of lipid-oligonucleotide conjugates. (A) Lipid conjugation to the 5′ or 3′ end of an oligonucleotide in solution [34][35][36][35,36,37]. (B) Lipid conjugation to the 5′ or 3′ terminus of an oligonucleotide on a solid support [28][30][29,31].

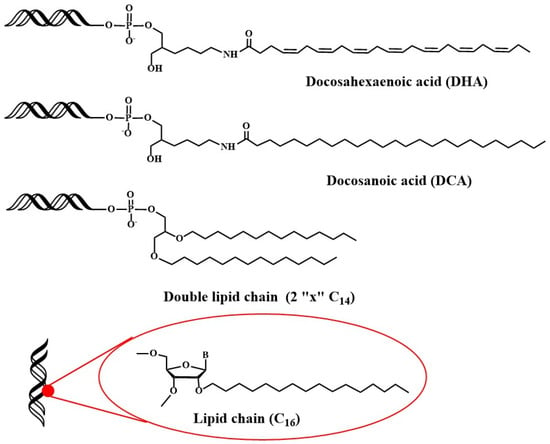

Recently, studies have been addressed towards the application of lipid-oligonucleotides to transfect cells and tissues other than liver. Primary neurons are difficult to transfect with siRNAs because the unique nature of the blood brain barrier (BBB) and the difficulty of direct administration [77][78]. Alterman et al. found that cholesterol-tetraethyleneglycol functionalized siRNA at the passenger strand was efficiently internalized in primary cortical neurons, inducing a potent and specific silencing of huntingtin gene [78][79][79,80]. This potent silencing activity was maintained in vivo when injected into mouse brain [78][79]. Additionally, docosahexaenoic acid conjugation (Figure 3) was judged to increase further the distribution and the inhibitory properties of lipid-siRNAs when administered into the brain [80][81].

Another interesting property of lipid-siRNAs is the enhancement of siRNA loading into extracellular vesicles [81][82][82,83], which generates attractive nanoparticles for the delivery of therapeutic siRNAs. The best option in terms of higher loading and efficiency was the conjugation of vitamin E (Sheme 1) [82][83]. Recently, siRNAs were modified with vitamin E by a benzonorbonadiene linker, which releases active siRNAs when reacting with tetrazines [83][84].

Next, the distribution of siRNAs conjugated to a small library of complex lipids was analyzed, including saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, steroids and lipophilic vitamins with or without phosphocholine heads. The level of hydrophobicity is critical in order to define accumulation in the liver or in the kidney. In addition, it was shown that some lipid derivatives were able to accumulate in non-hepatic tissues such as lung, muscle, heart, adrenal glands and fat [84][85][85,86]. In more detailed studies, factors such as the chemical structure of the lipids [85][86], the phosphorothioate content [86][87], the presence of single-stranded phosphorothioate regions [87][88] or the valency of fatty acid modifications [88][89] were demonstrated to affect the pharmacokinetics, the extrahepatic distribution and the in vivo efficacy of lipid-siRNAs [89][90][90,91]. Recently, the in vivo properties of siRNA carrying 2′-O-hexadecyl (C16) moieties have been described (Figure 3). These lipophilic siRNAs can be delivered into the central nervous system, eye and lungs of rats and non-human primates, where they exert inhibitory properties for at least 3 months [91][92]. These results opened the possibility of using lipophilic siRNAs in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

A systematic study on the effect of the conjugation of antisense oligonucleotides with fatty acids confirms its potential delivery to muscle and other extrahepatic tissues [92][93][93,94]. Moreover, palmitic acid-, tocopherol-, and cholesterol-conjugated (Scheme 1) antisense oligonucleotides were reported to increase protein binding and enhance intracellular uptake [94][95]. These properties were explored by several groups for the development of lipid-antisense oligonucleotides targeting the exon 51 of human Duchene Muscular Distrophy gene [95][96][96,97].

The development of mRNA vaccines, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, triggered the interest in lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. The approval of Onpattro for the treatment of transthyretin–mediated amyloidosis demonstrated the efficacy and safety of these non-viral vectors for siRNA delivery to liver [11]. This approval facilitated the rapid authorization of the two mRNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 [97][98][98,99]. The great potential of mRNA vaccines for cancer, infectious diseases and genetic disorders is stimulating the search for the next generation of lipid nanoparticles that would increase efficacy, degradability [99][100] and tissue-specificity properties [100][101].