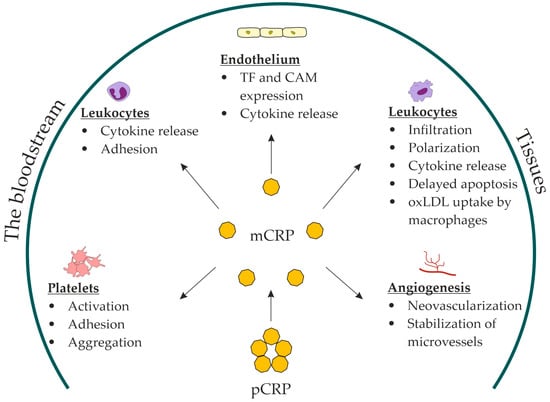

C-reactive protein (CRP) is the final product of the interleukin (IL)-1β/IL-6/CRP axis. Its monomeric form can be produced at sites of local inflammation through the dissociation of pentameric CRP and, to some extent, local synthesis. Monomeric CRP (mCRP) has a distinct proinflammatory profile. In vitro and animal-model studies have suggested a role for mCRP in: platelet activation, adhesion, and aggregation; endothelial activation; leukocyte recruitment and polarization; foam-cell formation; and neovascularization. mCRP has been shown to deposit in atherosclerotic plaques and damaged tissues.

CRP is the final product of the interleukin (IL)-1β/IL-6/CRP axis. Its monomeric form can be produced at sites of local inflammation through the dissociation of pentameric CRP and, to some extent, local synthesis. mCRP has a distinct proinflammatory profile. In vitro and animal-model studies have suggested a role for mCRP in: platelet activation, adhesion, and aggregation; endothelial activation; leukocyte recruitment and polarization; foam-cell formation; and neovascularization. mCRP has been shown to deposit in atherosclerotic plaques and damaged tissues.

- monomeric C-reactive protein

- mCRP

- C-reactive protein

- biomarker

- atherosclerosis

- inflammation

1. Introduction

2. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory IL-1β/IL-6/CRP Axis in Pathogenesis of Subclinical Vascular Inflammation

Cellular immune responses play a key role in all stages of atherosclerotic lesion development, from fatty streaks to plaque rupture [12][16]. A detailed discussion of cellular immunity in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis has been provided elsewhere [13][14][17,18]. Four types of cells are involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic lesions: smooth muscle cells (SMCs), T-lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. The cytoplasm of myeloid immune cells, including macrophages and neutrophils, and SMC contains pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) [15][16][19,20]. These receptors recognize exogenous pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). DAMPs arise from signals produced by injured cells and tissues in the absence of an exogenous pathogen [16][20]. One type of PRR is the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) [17][21]. The NLRP3 receptor in this group recognizes non-pathogenic DAMPs. NLRP3 activation leads to the formation of a molecular complex, the inflammasome, in the cytoplasm of myeloid immune cells. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a cytoplasmic protein complex that serves as a molecular platform for the activation of the cysteine protease caspase-1 [17][21]. Caspase-1 proteolyzes three proteins: pro-interleukin (pro-IL)-1β, pro-IL-18, and gasdermin D. Pro-IL-1β is converted into the active proinflammatory form of IL-1β and pro-IL-18 is converted into active proinflammatory IL-18. The activation of gasdermin D can induce pyroptosis, an inflammatory cell death, with the ensuing release of cytoplasmic content into surrounding tissues. This is particularly observed in the apoptosis of foam cells in atherosclerotic lesions [18][19][22,23]. The NLRP3 inflammasome formation has been observed in a number of diseases characterized by sterile inflammation. Uric-acid crystals can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in gout [20][24]. Furthermore, the NLRP3 inflammasome plays an important role in the development of abdominal aortic aneurysm [21][25], myocardial damage in ischemia-reperfusion injury [22][26], kidney damage in diabetes, gout, and acute renal failure [23][27]. Active oxygen species and free fatty acids activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in obesity [24][28] and diabetes [25][29], contributing to the development of insulin resistance [26][30]. In 2010, Duewell et al. demonstrated for the first time the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by cholesterol crystals [27][31]. CD36-mediated uptake of oxidized LDL by macrophages results in intracellular cholesterol crystallization. This disrupts phagocytosis and leads to the accumulation of cholesterol crystals in macrophage lysosomes [28][32]. Subsequently, cholesterol crystals damage lysosome membranes and are released along with the lysosomal protease cathepsin B. They interact with PRR in the cytoplasm and induce the NLRP3 inflammasome formation [29][33]. Calcium-phosphate crystals accumulated in calcified atherosclerotic plaques can also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [30][34]. Moreover, a recent study showed that CRP could activate the NLRP-3 inflammasome via the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) pathway [31][35]. The NLRP3 inflammasome activation triggers a central cascade of inflammatory signaling represented by IL-1β, IL-6, and CRP [32][36]. IL-1β and IL-6 are mainly produced by myeloid cells [33][34][37,38], whereas CRP is by hepatocytes [10]. IL-1β stimulates the release of chemokines and the expression of cell-adhesion molecules by endotheliocytes, facilitating leukocyte recruitment to the site of inflammation. IL-1β stimulates the proliferation of SMC and the secretion of chemokines and collagenases by macrophages, thus contributing to the destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques [35][39]. IL-1β induces IL-6 synthesis. IL-6 has a wide range of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties. For example, IL-6 stimulates the chemotaxis of neutrophils and macrophages to the site of inflammation [36][40]. It also stimulates chemokine release and expression of cell-adhesion molecules by endotheliocytes, facilitating leukocyte recruitment and platelet activation [37][41]. IL-6 produces a proatherogenic effect by stimulating SMC proliferation and modifying LDL uptake by macrophages and SMC [38][42]. Simultaneously, it stimulates an increase in LDL receptor expression, acting in an anti-atherogenic way [39][43]. IL-6 exhibits anti-inflammatory action by inhibiting IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) synthesis and increasing IL-1 receptor antagonists and soluble p55 TNF-α receptor release [40][44]. Despite both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects, higher levels of IL-1β and IL-6 are unequivocally associated with increased cardiovascular risk [41][45]. IL-6 stimulates CRP production in hepatocytes.3. Assessment of Residual Inflammatory Risk

3.1. C-Reactive Protein as a Biomarker of Subclinical Vascular Inflammation

CRP is the final product of the central inflammatory cascade. Owing to its excellent reproducibility, it is considered the main biomarker of inflammation that reflects the activity of the IL-1β/IL-6/CRP axis [32][36]. The CRP level is consistent over time. It is not affected by hematocrit or other blood-protein levels [42][46]. Moreover, it is unaffected by the circadian rhythm, time of food intake, blood sampling, anticoagulants, delay in specimen processing up to 6 h, or storage conditions. Nor is it affected by the specimen type: CRP measurements gave similar results in fresh, thawed, and even repeatedly thawed and refrozen plasma and serum. CRP can be measured using standard laboratory methods such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), turbidimetry, or nephelometry without significant discrepancies in results [42][46]. Thus, CRP is a convenient laboratory biomarker widely used in clinical practice and basic research. CRP levels rise manifold in response to infection or tissue damage: from 5–10 mg/L in mild cases to 320–550 mg/L in the most severe cases [43][44][47,48]. However, in atherosclerosis CRP levels are usually below 5 mg/L. A high-sensitivity assay with a threshold of 0.28 mg/L was developed to measure CRP below this level [45][49]. Large prospective observational studies have demonstrated that in surveyed populations, CRP levels were within tertiles of less than 1.0 mg/L, 1–3 mg/L, and more than 3.0 mg/L. In meta-analyses, the odds ratio for MACE between the lower and upper tertiles was between 1.58 and 2.0 [46][47][50,51]. The PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial demonstrated that, in patients on aggressive statin therapy, the median CRP level was 2.0 mg/L. Patients with a CRP level of 2.0 mg/L or more had a 30% higher relative risk of MACE [48][52]. Similar CRP-level medians and cardiovascular risk ratios were observed in subsequent large clinical trials of statin therapy [49][50][53,54]. Currently, a CRP level 2.0 mg/L or more is suggested by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention as a cardiovascular risk factor [9]. The association between the CRP level and MACE rate has been examined in large observational studies in postmenopausal women [51][55], healthy volunteers in the Physicians’ Health Study [52][56], and MRFIT [53][57]. A meta-analysis of 52 prospective studies that included 246,669 individuals without cardiovascular disease showed that increased CRP levels worsened the 10-year prognosis of cardiovascular risk [54][58]. In addition, a meta-analysis of the East Asian population showed an association between elevated CRP and higher cardiovascular risk [55][59]. Furthermore, the USPSTF meta-analysis that explored studies published from 1966 to 2007 demonstrated that relative cardiovascular risk is 1.58-fold higher in individuals with a CRP level more than 3.0 mg/L than in those with a CRP level less than 1.0 mg/L [46][50].3.2. Pentameric C-Reactive Protein

pCRP belongs to the pentraxin family of acute-phase proteins. It is the primary acute-phase reactant in humans. pCRP is synthesized in hepatocytes and secreted into the bloodstream upon stimulation with IL-6. Circulating pCRP consists of five monomeric subunits bound with disulfide bonds in a ring-shaped disk [56][60]. Each subunit of the pentameric disk has a calcium-dependent binding site for lysophosphatidylcholine on one side and the complement component C1q on the other [57][58][61,62]. Phosphatidylcholine is a major structural component of cell and extracellular vesicle membranes. It is mainly present on the outer leaflet of the membrane phospholipid bilayer [59][63]. Secretory phospholipase A2 (PLA2) hydrolyzes it to lysophosphatidylcholine. Normally, phosphatidylcholine does not interact with PLA2. However, during apoptosis and cell injury, phospholipids of the inner leaflet translocate to the outer leaflet of the cell membrane. These phospholipids include phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine, which are PLA2 ligands. In the presence of these two phospholipids, PLA2 hydrolyzes phosphatidylcholine to biologically active lysophosphatidylcholine [59][63]. In oxidized LDL, lipoprotein-associated PLA2 cleaves phosphatidylcholine in the lipid monolayer to lysophosphatidylcholine [60][64]. Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulates the endothelial synthesis of several chemokines, impairs endothelium-dependent arterial relaxation, increases oxidative stress, suppresses endotheliocyte migration and proliferation, and facilitates macrophage activation and polarization to the inflammatory M1 phenotype [61][65]. Lysophosphatidylcholine of oxidized LDL contributes to lysosomal damage and the NLRP-3 inflammasome activation in foam cells [62][66]. Lysophosphatidylcholine can activate the NLRP-3 inflammasome in adipose tissue, contributing to the development of insulin resistance [63][67]. Lysophosphatidylcholine is a ligand for pCRP [64][68]. Circulating pCRP acts as an opsonin that binds to lysophosphatidylcholine on the surface of cell membranes and oxidized lipoproteins. The sites on the reverse side of the CRP disc interact with the complement component C1q. This results in activation of the classical complement cascade up to the C4 component. Thus, CRP-induced complement activation facilitates phagocytosis of damaged cells and oxidized lipoproteins but does not initiate the formation of the membrane-attack complex C5b–C9 [64][68]. pCRP can also interact with factor H and activate the complement cascade up to the C4 component via the alternative pathway [65][69]. Furthermore, pCRP can opsonize nuclear antigens released by apoptotic and necrotic cells [66][70]. Therefore, the biological role of circulating pCRP is characterized by the facilitation of the clearance of cell-destruction products formed during trauma, infection, or sterile inflammation.3.3. Monomeric C-Reactive Protein

Upon binding to lysophosphatidylcholine, the pentameric disk of CRP undergoes dissociation through intermediate forms into the final product, mCRP [67][68][71,72]. Dissociation occurs through the disintegration of disulfide bonds between the pCRP subunits [69][73]. This process involves lysophosphatidylcholine but also requires other cell-membrane components and calcium. Soluble lysophosphatidylcholine does not dissociate pCRP in the absence of cell membranes [68][72]. Dissociation opens a neoepitope (octapeptide Phe-Thr-Lys-Pro-Gly-Leu-Trp-Pro) on the C-terminal end of monomeric subunits, which is concealed in the pentameric disk [68][72]. This dramatically changes the antigenic specificity and biological functions of CRP [70][74]. mCRP has reduced aqueous solubility and remains predominantly bound to the cell membranes [71][75]. It has been detected in extracellular vesicles circulating in the bloodstream. A pronounced increase in the number of mCRP-positive extracellular vesicles has been observed in patients with acute myocardial infarction [72][76] and peripheral artery disease [73][77]. mCRP in monocyte-derived exosomes has also been detected in patients with stable coronary artery disease [74][78]. mCRP may contribute to thromboinflammation. Thromboinflammation has recently been introduced to describe the complex interplay between blood coagulation and inflammation [75][79]. Immobilized on a collagen substrate, mCRP substantially increased platelet adhesion and thrombus growth rate at the shear rate of 1500 s−1, characteristic of arteries with mild stenosis [76][80]. Perfusion of mCRP-preincubated whole blood over a collagen type I-coated flow chamber yielded a similar result [76][80]. Unlike pCRP, mCRP induced platelet glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa activation in a dose-dependent manner. mCRP facilitated platelet adhesion via activation of GP IIb/IIIa receptors. Moreover, pCRP dissociated into mCRP on activated adhered platelets during the perfusion of whole blood through a flow chamber [77][81]. Without dissociation, pCRP did not stimulate platelet adhesion or thrombus growth [76][77][80,81]. pCRP was attached to platelet membranes and dissociated into mCRP in another experiment with perfusion of whole blood over a surface coated with activated adhered platelets. GP IIb/IIIa inhibition with an antibody (abciximab) prevented pCRP dissociation [78][82]. mCRP stimulated platelet adhesion to the endothelial cells [79][83] and induced tissue-factor expression and fibrin formation on endothelial cells [80][84]. When dissociated on platelets and adhering to the vessel wall, mCRP can induce endothelial activation and leukocyte recruitment. mCRP enhanced endothelial activation and neutrophil attachment to the endothelium [79][81][83,85]; monocyte adhesion to the collagen [82][86], fibrinogen [83][87], and fibronectin matrix [84][88]; and T-lymphocyte extravasation [85][89]. In vitro, mCRP decreased nitric-oxide release and increased production of proinflammatory IL-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by endothelial cells via the NF-kB pathway [86][90]. Moreover, mCRP stimulated leukocyte recruitment to the vessel wall, inducing the expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectin, as well as the production of IL-6 and IL-8 by the endothelium [79][86][87][83,90,91]. mCRP induced IL-8 production [71][88][75,92] and prevented neutrophil apoptosis [71][75]. In addition, mCRP stimulated macrophage and T-cell polarization to inflammatory M1 and Th1 phenotypes [89][93]. mCRP stimulated oxidized LDL uptake by macrophages [90][94]. The in vivo evidence that mCRP can stimulate monocyte infiltration into damaged tissues was obtained from recent studies on a murine model of myocardial infarction [91][95] and a rat model of renal ischemia/reperfusion injury [92][96]. Compared with controls, the infarcted myocardium of mCRP-pretreated mice demonstrated increased accumulation of macrophages of the inflammatory M1 phenotype [91][95]. Furthermore, the damaged renal tissue of pCRP-pretreated rats demonstrated increased infiltration with monocytes colocalized with mCRP [92][96]. In addition, mCRP has been shown to stimulate neoangiogenesis and stabilize novel microvessels in vitro (bovine aortic endothelial cells and SMC) and in vivo (chorioallantoic membrane) [93][94][97,98]. In summary, the role of mCRP has been suggested in: platelet activation, adhesion, and aggregation; endothelial activation; leukocyte recruitment and polarization; foam-cell formation; and neovascularization (Figure 1).