Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Tudor Sorin Pop and Version 2 by Peter Tang.

A biomaterial is a nonviable material used in a medical device, intended to interact with biological systems. In the field of orthopedics, implantology challenges emerge at the border of local reactions to metallic implants with personalized implant surfaces and general inflammatory reactions as a result of host–implant response.

- biocompatibility

- implant

- degenerative joint diseases

1. Introduction

An increasing number of diagnosed degenerative joint pathologies in the foreseeable near future is projected [1]. General increase in life expectancy and quality of life facilitates patients access to regular medical examinations and are expected to increase the prevalence of certain degenerative joint diseases [2]. Secondary to this, a growth in their incidence both nationally and globally is also expected, bringing a rising demand for innovative and durable implantable devices in the field of orthopedics [3]. Currently, the prevalence of degenerative joint disease on the Eastern European continent is rising (13.4% in 2020) which drags demand for large-scale implantable devices [4]. A highlight in increasing prevalence of degenerative joint diseases in younger people is also anticipated. In addition to socio-economic and functional impact, there is the issue of properties related to mechanical strength, osseointegration and durability of the implant. Enhancing various properties of a specific implant requires a multidisciplinary approach with aid from interconnection of different specialties such as: material engineering, cell biology, orthopedic surgery and not only [5].

Presently, the world is endorsing a growing need for materials and implants of various tissues and the permanent development of cell culture in vitro studies is an upright practical instrument for investigating the biocompatibility of future implantable materials. As a response to the well-known three “Rs” (“reduction”, “refinement” and “replacement”) brought to literature by English academics in the 1960s, in vitro biocompatibility research has been reduced and, in most cases, diminished to laboratory studies that no longer or drastically reduce animal sacrifice [6].

2. Biomaterial: Brief History and Definition

There are plenty of historical descriptions and reports of procedures for introducing different types of devices in the human body [1][2][1,2]. These ancient reports include procedures performed for replacing teeth, different bony structures or wound regeneration attempts [3]. However, biocompatible materials did not exist as we distinguish them today. Throughout history, the word “biomaterial” per se was not used in academic language and it was reported under distinctive names. The term was mostly synonymous with “implantable device”, “prosthesis”, “material augment”, etc. In the mid-18th century, as scientific communities became more robust and industrialized, the area of implantable materials gained additional popularity. It was in the middle of 19th century when conferences and scientific gatherings around the world began methodically focusing on implantable devices and their usage as replacements in different anatomic parts. The first “almost-definition” of a biomaterial was made in 1967 by pioneer orthopedic surgeon Jonathan Cohen [4]. He defined all materials (metals, bone and derivatives used as bone grafts, plastics ceramics and composites) as “biomaterials” excluding drugs and fabrics used for sutures [5]. Only two years later, several symposiums were organized focusing predominantly on materials and their use for reconstructive surgery. Society For Biomaterials was founded by Dr. William Hall and his colleagues in 1974 with the aid of visionary bioengineers from Clemson University [6]. Therefore, a newly emerged organization was established and was set to accurately institute a new definition for the concept of biomaterials: “A biomaterial is a systematically, pharmacologically inert substance designed for implantation within or incorporation with a living system” [7]. Further on, a definition published by British professor David F. Williams gained wide criticism throughout previous decades [8][9][8,9]. He stated that a biomaterial is “a nonviable material used in a medical device, intended to interact with biological systems” [10]. It not only lacked explanations made on what precisely “nonviable” means, but the exclusion of biological tissues (bone grafts, tendons, ligaments, etc.) combined with various pharmacological products conveyed numerous controversies in the literature. As of today, half a century after the first attempts, the definition does not seem too far away but definitely multidisciplinary. The latest definition was proposed in United Kingdom in 1986 and approved afterwards in 1991 in a proceedings paper of Consensus Conference held by the European Society for Biomaterials: “Any substance or combination of substances, other than drugs, synthetic or natural in origin, which can be used for any period of time, which augments or replaces partially or totally any tissue, organ or function of the body, in order to maintain or improve the quality of life of the individual” [11]. The state-of-the-art definition agrees clearly and analytically on its previous troubling mentions and avoids almost every bias. It is a well-defined traceable result of several multidisciplinary meetings, mutual agreements and pooled opinions.3. The Orthopedic Biomaterial

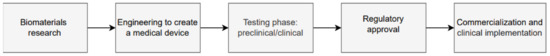

Up until a few decades ago, a new biomaterial introduced in the commercial lines of implantable devices manufacturers consisted of new bulk technologies such as: stents, wires, titanium cerclages, biodegradable screws and so on. Emerging concepts in present-day technology include extremely advanced biomaterials and include targeting nanocarriers with specially designed localized delivery systems [12]. In the field of orthopedics, implantology challenges emerge at the border of local reactions to metallic implants with personalized implant surfaces and general inflammatory reactions as a result of host–implant response [13]. While characteristics and occurrences of implantable device allergies seem to be left aside [14], an in-depth breakdown of adverse local reactions and methods of improving bone–implant interface osseointegration seem to arise [15]. Another breaking topic of significance remains around improving implants surface at a micro and more innovative, at nano scale level. This mainly consists of coating specific surfaced areas of implants [16][17][16,17] (e.g., trochanteric region of femoral stem, femoral condyle region of knee prosthesis). These procedures are generally advancing with numerous in vitro studies and subsequently implemented in clinical trials [18]. A detailed look at the steps involved in defining a good biocompatible implant is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Steps that are mandatory to bring potentially innovative biomaterial technology to an implantable level.

4. From Laboratory to Clinical Practice: In Vitro Biocompatibility Testing

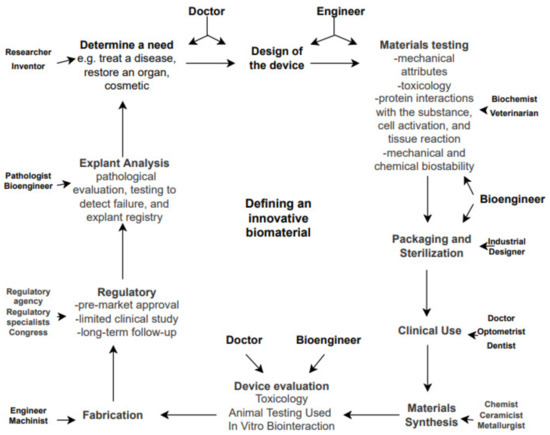

In the previous three decades, immense attention was ascribed to in vitro biocompatibility studies of novel biomaterials, consequently being detrimental to in vivo studies. An expectable outcome was a progress on cell-biomaterial interaction theories (cell adhesion, proliferation, viability, material roughness, surface adaptation, etc.) that resulted in a fast development of novel in vitro study models, products and their implementation in clinical practice [25]. After identifying the need for an improvement of a biomaterial, surface or feature, a clear description of novel mechanical properties is established. Cytotoxic testing commonly begins simultaneously with cell culture analysis in vitro and according to several authors they are followed by fluorescent staining of different types [26]. Culture testing implies an in-depth analysis of protein interactions and synthesis, cell viability, adhesion and proliferation processes [27]. Several particularities of each step involved are described in detail in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Disciplines involved in biomaterials science and the path from a need to a manufactured medical device.