Huanglongbing (HLB, aka citrus greening), one of the most devastating diseases of citrus, has wreaked havoc on the global citrus industry in recent decades. The culprit behind such a gloomy scenario is the phloem-limited bacteria “Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus” (CLas), which are transmitted via psyllid. To date, there are no effective long-termcommercialized control measures for HLB, making it increasingly difficult to prevent the disease spread. To combat HLB effectively, introduction of multipronged management strategies towards controlling CLas population within the phloem system is deemed necessary. This articlentry presents a comprehensive review of up-to-date scientific information about HLB, including currently available management practices and unprecedented challenges associated with the disease control. Additionally, a triangular disease management approach has been introduced targeting pathogen, host, and vector. Pathogen-targeting approaches include (i) inhibition of important proteins of CLas, (ii) use of the most efficient antimicrobial or immunity-inducing compounds to suppress the growth of CLas, and (iii) use of tools to suppress or kill the CLas. Approaches for targeting the host include (i) improvement of the host immune system, (ii) effective use of transgenic variety to build the host’s resistance against CLas, and (iii) induction of systemic acquired resistance. Strategies for targeting the vector include (i) chemical and biological control and (ii) eradication of HLB-affected trees. Finally, a hypothetical model for integrated disease management has been discussed to mitigate the HLB pandemic.

- HLB pandemic

- citrus greening

- Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus

1. Introduction

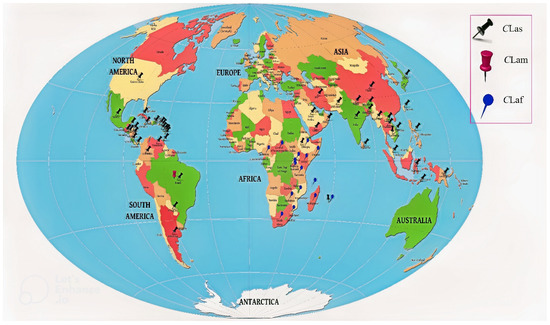

| Sr. No | Continent/Country/Region | Distribution of HLB | Causal Organism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | ||||

| 1 | Bangladesh | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [21] |

| 2 | Bhutan | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] |

| 3 | Cambodia | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [23] |

| 4 | China | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] |

| 5 | India | Present, Widespread | Ca |

| Sr. No | Candidatus Liberibacter spp. | Strain | Host | Sample Origin | Genome Size (Mb) | Number CDS Present in the Genome | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | A4 (CP010804.1) |

Citrus reticulata | China: Guangdong | 1.23025 | 1067 | [59] | |||||

| 2 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | Gxpsy (CP004005.1) |

Diaphorinacitri | China: Guangxi | 1.26824 | 1094 | [57] | |||||

| 3 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | JRPAMB1 (CP040636.1) |

Diaphorinacitri | USA: Florida | 1.23716 | 1072 | [62] | |||||

| 4 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | TaiYZ2 (CP041385.1) | Citrus maxima | Thailand: Songkhla | 1.23062 | 1067 | [77] | |||||

| 5 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | psy62 (CP001677.5) |

- | USA: Florida | 1.22732 | 1049 | [56] | |||||

| 6 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | JXGC (CP019958.1) | . Liberibacter asiaticus | Citrus[24] | ||||||||

| China: Jiangxi | 1.22516 | 1033 | [ | 60 | ] | 6 | Indonesia | |||||

| 7 | Candidatus | Present | Liberibacter asiaticus | Ishi-1 (AP014595.1)Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus |

[25] | |||||||

| Diaphorinacitri | Japan: Ishigaki | 1.19085 | 1001 | [ | 58 | ] | 7 | Iran | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [26] | |

| 8 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | AHCA1 (CP029348.1) |

Diaphorinacitri | USA: California | 1.23375 | 1056 | [61] | 8 | Japan | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [27] |

| 9 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | FL17 (JWHA00000000.1) |

Citrus | USA: Florida | 1.22725 | 1019 | [78] | 9 | ||||

| 10 | Laos | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | YNJS7C (QXDO00000000)[23] |

|||||||

| Citrus | China: Yunnan | 1.25898 | 1102 | [ | 79 | ] | 10 | Malaysia | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [24] | |

| 11 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | YCPsy LIIM00000000) |

Diaphorinacitri | China: Guangdong | 1.233647 | 1037 | [80] | 11 | Myanmar | |||

| 12 | Candidatus | Present | Liberibacter asiaticus | LBR19TX2 (VTMA00000000Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus |

[23] | |||||||

| - | USA: Texas | 1.20275 | 1008 | [ | 67 | ] | 12 | Nepal | Present, Widespread | |||

| 13 | Candidatus | Ca | . Liberibacter asiaticus | Liberibacter asiaticus[28] | ||||||||

| LBR23TX5 | (VTMB00000000) | - | USA: Texas | 1.20347 | 1009 | [67] | 13 | Oman | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [ | |

| 14 | 22 | ] | ||||||||||

| Candidatus | Liberibacter asiaticus | AHCA17 (VNFL00000000) |

Citrus maxima | USA: California | 1.20862 | 1036 | [81] | 14 | ||||

| 15 | Pakistan | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticusPresent | YNXP-1 Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus |

(VIGA00000000)[29] | ||||||||

| Cuscuta | China: Yunnan | 1.20707 | 15 | Philippines | Present, Widespread | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [29] | |||||

| 16 | Saudi Arabia | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [30] | ||||||||

| 17 | Sri Lanka | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 1031 | - | 18 | Taiwan | Present, Widespread | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||

| 19 | Thailand | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [31] | ||||||||

| 20 | Vietnam | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [32] | ||||||||

| 21 | Yemen | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [30] | ||||||||

| North America | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | |||||||||||

| 22 | Barbados | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 23 | Belize | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [17] | ||||||||

| 24 | Costa Rica | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 25 | Cuba | Present, Widespread | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 26 | Dominica | Present, Few occurrences | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 27 | Dominican Republic | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 28 | El Salvador | Present | Unknown | [33] | ||||||||

| 29 | Guadeloupe | Present, Localized | Unknown | [34] | ||||||||

| 30 | Guatemala | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 31 | Honduras | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 32 | Jamaica | Present, Widespread | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 16 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | SGCA16 (VTLZ00000000) |

- | USA: San Gabriel | 1.20994 | 1015 | [67] | |||||

| 17 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | JXGZ-1 (VIQL00000000) |

Cuscuta | China: JiangXi | 1.21799 | 1040 | - | |||||

| 18 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | DUR1TX1 VTLT00000000.1) |

- | USA: Texas | 1.20629 | 1011 | [67] | |||||

| 19 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | Mex8 (VTLU00000000.1) |

- | Mexico: Mexicali | 1.24313 | 1042 | [67] | |||||

| 20 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | SGCA5 (LMTO00000000.1) |

Orange citrus | USA: San Gabriel | 1.20138 | 1001 | [80] | |||||

| 21 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | CHUC (VTLV00000000) |

- | China | 1.20845 | 1032 | [67] | |||||

| 22 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | TX2351 (MTIM00000000) |

Asian citrus psyllid | USA: Texas | 1.252 | 1129 | [82] | |||||

| 23 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | GFR3TX3 (VTLR00000000) |

- | USA: Texas | 1.20932 | 1013 | [67] | |||||

| 24 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | HHCA16 (VTLY00000000) |

- | USA: Hacienda Heights | 1.20705 | 1012 | [67] | |||||

| 25 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | MFL16 (VTLX00000000) |

- | USA: Florida | 1.19922 | 1012 | [67] | |||||

| 26 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | DUR2TX1 (VTLS00000000) |

- | USA: Texas | 1.21232 | 1009 | [67] | |||||

| 27 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | CRCFL16 (VTLW00000000) |

- | USA: Florida | 1.20828 | 1028 | [67] | |||||

| 28 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | HHCA (JMIL00000000.2) |

Citrus sp. | USA: Hacienda Heights | 1.15062 | 867 | [59] | |||||

| 29 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | TX1712 (QEWL00000000) |

Citrus sinensis | USA: Texas | 1.20333 | 0 | [83] | |||||

| 30 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | SGpsy (QFZJ00000000.1) |

Diaphorinacitri | USA: San Gabriel | 0.769888 | 0 | [61] | |||||

| 31 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | SGCA1 (QFZT00000000.1) |

USA: San Gabriel | 0.233414 | 557 | [61] | ||||||

| 32 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | YCPsy (LIIM00000000) |

Diaphorinacitri | Guangdong, China | 1.233647 | - | [80] | |||||

| 33 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | PA19 (WOXD01000000) | Kinnow mandarin | Pakistan | 1.224156 | 1059 | [84] | |||||

| 34 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | PA20 (WOUN01000000) | Kinnow mandarin | Pakistan | 1.226225 | 1062 | [84] | 33 | Martinique | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [ |

| 35 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | 34 | ] | |||||||||

| CoFLP1 | (CP054558.1) | Diaphorinacitri | Colombia: Municipio Dibulla |

1.231639 | 1048 | [64] | 34 | Mexico | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [ | |

| 36 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | 22 | ] | |||||||||

| 9PA (JABDRZ000000000.1) | Citrus sinensis | Brazil (South America) | 1.231881 | - | [ | 85 | ] | 35 | Nicaragua | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] |

| 37 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | MFL16 (VTLX00000000) |

Citrus | USA: Florida | 1,199,225 bp | - | [67] | 36 | Panama | |||

| 38 | Present, Localized | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| CRCFL16 (VTLW00000000) | Citrus | USA: Florida | 1,208,280 bp | - | [ | 37 | Puerto Rico | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||

| 38 | Trinidad and Tobago | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 39 | U.S. Virgin Islands | Present, Few occurrences | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 40 | United States | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 67 | ] | |||||||||||

| 39 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | ReuSP1 (CP061535.1) |

Diaphorinacitri | France: La Reunion | 1.230064 | 1043 | [65] | |||||

| 40 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | Tabriz.3(JAKQYA000000000.1) | Elaeagnus angustifolia | Iran: East Azerbaijan, Tabriz | 1.22409 | 589 | - | |||||

| 41 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | YNHK-2 (WUUB01000000.1) |

Citrus | China: Yunnan | 1.08957 | - | [86] | |||||

| 42 | Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | A-SBCA19 (JADBIB010000000.1) |

Diaphorinacitri | USA: California, San Bernardino County | South America | |||||||

| 41 | Argentina | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| Brazil: Sao Paulo | 1.17607 | 42 | Brazil | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter americanus and Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [9] | ||||||

| 43 | Colombia | Present, Few occurrences | Ca.Liberibacter asiaticus | [22] | ||||||||

| 44 | Paraguay | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [35] | ||||||||

| 45 | Venezuela | Present | Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus | [36] | ||||||||

| Africa | ||||||||||||

| 46 | Burundi | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [37] | ||||||||

| 47 | Cameroon | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [37] | ||||||||

| 48 | Central African Republic | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [37] | ||||||||

| 49 | Comoros | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [22] | ||||||||

| 50 | Eswatini | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [38] | ||||||||

| 51 | Ethiopia | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus and Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus |

[37] | ||||||||

| 52 | Kenya | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [29] | ||||||||

| 53 | Madagascar | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [38] | ||||||||

| 54 | Malawi | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [37] | ||||||||

| 55 | Mauritius | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus and Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus |

[22] | ||||||||

| 56 | Rwanda | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [37] | ||||||||

| 57 | Somalia | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [22] | ||||||||

| 58 | South Africa | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [39] | ||||||||

| 59 | Tanzania | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [38] | ||||||||

| 60 | Uganda | Present | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [40] | ||||||||

| 61 | Zimbabwe | Present, Localized | Ca. Liberibacter africanus | [29] |