Glycosylation abnormalities have been reported in autoimmune diseases such as IgA nephropathy, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and multiple sclerosis

[8][9][8,9]. For example, galactose deficiency in immunoglobulin G (IgG) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis correlates with disease progression

[10]. Galactose deficiency in immunoglobulin G has also been reported in other diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease

[11] and multiple sclerosis

[12]. In addition, decreased immunoglobulin G fucosylation is a marker of autoimmune thyroid diseases

[8].

2. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that can affect every organ and system in the body. It presents a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations in acute periods and periods of remission. In mild forms, skin and joint manifestations are observed; in severe forms, it affects the kidneys, heart, and nervous system

[13][14]. SLE develops mainly in women of reproductive age, in a ratio of nine women to one man

[14][15].

Etiopathogenesis of SLE involves immunological, genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors that play an important role in the regulation of immunological tolerance

[13][15][14,16]. B cells and their various subpopulations play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of SLE. These cells show abnormal activation through their B cell receptor and Toll-like receptors

[16][17]. Another factor that favors the activation of B cells in SLE is altered levels of cytokines such as interferons alpha (IFNɑ), beta (IFNβ), and gamma (IFNɣ), as well as BAFF/Blys, which promote B cells survival

[16][17][17,18].

Serum of SLE patients is characterized by having autoantibodies against antigens such as double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), RNA, ribonucleoproteins (rRNA/Ro, La, Smith), and cytoskeletal antigens

[18][19]. The autoantibodies in SLE patients are of a high affinity and IgG type, indicating that an isotype switch has occurred, for which the participation of T cells is required

[19][20]. T cells from SLE patients overexpress the CD40L molecule, which allows them to provide costimulatory signals necessary for B cell differentiation, proliferation, and isotype switching

[20][21].

The fundamental role of T cells in the etiopathogenesis of SLE is supported by studies in murine models, where mice develop lupus spontaneously. While in NZB/NZW F1(B/W) mice, T cells elimination by monoclonal antibodies prevented disease development

[21][22]; as well as the fact that the hybrid nu/nu NZB/NZW F1 (B/W) mice, which lack a thymus, do not develop lupus

[22][23].

3. Glycosylation

3.1. O-Glycosylation

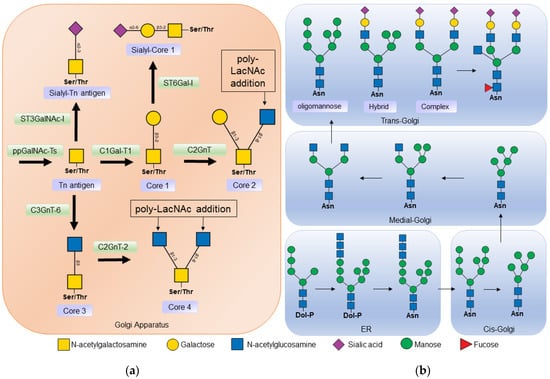

In

O-glycosylation,

N-acetyl-galactosamine (GalNAc) residues are added from

N-acetyl-galactosamine-uridine diphosphate (UDP-GalNAc) by the action of

N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferase (ppGalNAcT). At least 21 isoforms of this enzyme have been described, which have different affinities depending on the amino acid sequence and the three-dimensional arrangement of carbohydrate residues

[23][24][26,27]. The binding of

N-acetyl-galactosamine (GalNAc) to the serine or threonine of a protein is known as the Tn antigen. In a second step, galactose (Gal) is added to the

N-acetyl-galactosamine residue in the β1-3 bond, by the action of Core 1 β1-3 galactosyltransferase (C1GalT-1), to form the structure known as core 1 (

Figure 12a)

[2][25][2,28].

Figure 12. (a) Biosynthesis of O-glycans. O-glycosylation occurs in the Golgi apparatus, where N-acetyl-galactosamine is linked to a serine or threonine residue by the action of polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (ppGalNAc-Ts) forming the Tn antigen. Core 1 β1-3 galactosyltransferase 1 (C1Gal-T1) then binds to a galactose to form core 1. Core 1 can be a substrate for some sialyltransferase or core 2 β1-6 N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (C2GnT) to thus form core 2. Core 3 is formed from insufficient Tn by the action of core 3 β1-3 N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 6 (C3GnT-6); in turn, core 3 is a substrate to form core 4 by the addition of another N -acetyl-glucosamine by Core 2/4 β1-6 N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 2 (C2GnT-2). (b) Biosynthesis of N-glycans. Synthesis begins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where a dolicholphosphate oligosaccharide is transferred to an asparagine residue by oligosaccharyltransferase (OST). Next, α-glucosidases I and II, and α-mannosidase I cleave the sugars from the oligosaccharide. The protein is then transported to the Golgi apparatus, where other mannosidase result from the processing of the N-glycan. In the middle part of the Golgi apparatus, N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1 (MGAT1) adds N-acetyl-glucosamine to begin the synthesis of hybrid and complex N-glycans. In the Trans Golgi part, fucoses, sialic acids, and poly-lactosamine chains, α2-6 sialyltransferase (ST3GalNAc), α2-6 sialyltransferase (ST6Gal), poly-N-acetyllactosamine (Poly-LacNAc) are added.

Core 1 may be a substrate for the enzyme core 2 β1-6

N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (C2GnT), which catalyzes the addition of

N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) at the β1-6 bond with galactose

[25][28]. Two isoforms of this enzyme have been described: the L type that synthesizes core 2, and the M type that also participates in the synthesis of other cores

[2][26][2,29]. Core 2 is produced at many sites, including the intestinal mucosa, on activated T cells, and during embryonic development. The synthesis of cores 3 and 4 is mainly restricted to sites such as the mucosal epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract, the respiratory tract, and the salivary glands

[2][26][2,29].

3.2. N-Glycosylation

The first sugar to be attached to eukaryotic

N-glycans is

N-acetyl-glucosamine, which is linked to the asparagine residue via an

N-glycosidic bond in the consensus sequence Asn-X-Ser/Thr, where X is any amino acid except proline.

N-glycans affect the conformation, solubility, antigenicity, activity, and recognition of proteins

[1].

N-glycans have a common core sequence and are classified into three types based on the branches they contain. Oligomannose types contain only mannose residues in the branches, complex types have

N-acetyl-glucosamine-initiated branches, and hybrid types have both mannose-initiated and

N-acetyl-glucosamine-initiated branches (

Figure 12b).

N-acetyl-glucosamine-initiated branches can be lengthened by the addition of

N-acetyl-lactosamine (Galβ1-4GlcNAc) repeats, which are ligands for endogenous lectins such as galectins

[1][27][1,32].

The synthesis of

N-glycans begins in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum with the addition of 14 sugars to the lipid molecule dolichol-phosphate. Then this oligosaccharide is transferred by oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) to an asparagine protein. In the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, the 14-sugar oligosaccharide is cleaved by α-glucosidase I (MOGS) and α-glucosidase II (GANAB)

[1]. This step is important in protein folding, as chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum recognize the cleaved

N-glycans

[28][33].

4. Functions of Glycosylation in the Immune System

Glycosylation affects the conformation, stability, charge, protease resistance, and affinity of the proteins for other proteins

[3]; that is, it is part of the regulation of ligand–receptor interactions. During the inflammation process, the receptor proteins involved in migration, adhesion, and diapedesis are differentially glycosylated, thus they are recognized by their ligands

[3].

In the case of T cells, protein glycosylation is a dynamic process and changes depending on the stimuli they receive; for example, the pattern of glycosylation between naïve T cells and active T cells is different

[29][37]. When the T cell is activated by stimuli through its T cell receptor (TCR), an increase in Tn antigen on glycoproteins is observed, as recognition of these cells by

Arachis hypogaea agglutinin (PNA) and

Helix pomatia agglutinin, two lectins with an affinity for the Tn antigen, is increased

[30][31][32][38,39,40].

Glycosylation also regulates T cell activation and maturation by affecting the affinity between the T cell receptor complex and the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Glycosylation of membrane receptors such as CD4, CD8, and T cell receptors has been shown to alter the affinity of interactions with the MHC, thereby affecting positive selection (Zhou et al., 2014). In addition, the presence of sialic acid in position α2-3 in core 1 of the O-glycans of the CD8 co-receptor decreases the avidity for MHC class I molecules, which plays an important role in negative selection. Glycosylation is also involved in the control of T cell differentiation. Decreased CD25 glycosylation has been shown to prevent T cell differentiation to the Th1, Th2, and Treg-induced phenotype, but promotes Th17 cell differentiation

[33][41].

Glycoprotein sialylation is another important factor that regulates the interaction between receptors and their ligands. The interaction between CD69 and the S100A8/S100A9 complex is important in Treg cell differentiation, but the removal of sialic acid by sialidase treatment on activated CD4 T cells prevents binding between these proteins and decreases Treg cells differentiation

[34][42].

Therefore, alterations in glycosylation lead to changes in the T cell-mediated immune response and have been linked to inflammation and autoimmune diseases

[9][35][9,43]. For example, treatment of mice with glucosamine decreases CD25 glycosylation, prevents differentiation to Th1 cells, increases islet graft survival in diabetic mice, and exacerbates the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalitis

[33][41].

In this regard, it has been shown that naïve, memory, and germinal center B cells express triantennary and tetraantennary

N-glycans with long chains of poly-

N-acetyl-lactosamine; these chains show specific differences that allow them to be ligands for certain galectins

[36][44]. Galectins are lectins secreted by different cells, such as endothelial cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells, which recognize lactosamine in

O- and

N-glycans expressed in membrane proteins. The binding of galectins to their ligands triggers signals related to inflammation, activation, and death of target cells

[37][45].

In B cells, the interaction of glycans and galectins regulates processes such as activation (galectin 3 and 9), plasma cell differentiation (galectin 1 and 8), and survival (galectin 1)

[7]. Alterations in glycosylation have effects on the affinity for galectins. For example, in germinal center B cells, it has been observed that the addition of the disaccharide β1,6

N-Acetyl-glucosamine-galactose to the poly-

N-acetyl-lactosamine chains prevents the binding of galectin 3 and 9

[36][38][44,46].

In B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, B-cell glycosylation is altered in a way that allows interaction with galectin 1, thereby lowering the B cell receptor (BCR) signaling threshold; this causes the signaling and survival of these B cells; in addition, the interaction of galectin 1 with glycans stimulates the expression of BAFF and APRIL that promote cell survival

[39][48].

5. Alterations in Glycosylation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

5.1. Alterations in B Cell Glycosylation and Antibodies in SLE

In the case of B cells, glycosylation studies have been directed primarily at immunoglobulins. It has been proposed that the acquisition of

N-glycosylation sites in the variable regions of immunoglobulin light or heavy chains could favor B cell survival during germinal center selection, providing B cells with an additional mechanism for the generation of autoreactive cells

[40][41][68,69].

5.1.1. Glycosylation of Constant Regions

SLE patients have alterations in the glycosylation of immunoglobulin G. A greater recognition of the

Aleuria aurantia lectin, which has an affinity for fucosylated residues, has been observed in comparison with healthy individuals; recognition of this lectin correlates with disease activity

[42][61]. Antibodies with reduced fucosylation of their Fc region have a better interaction with the Fc gamma receptor IIIa (FcgRIIIa)

[43][44][53,70].

Increased recognition of the Lens culinaris lectin, which is specific for the core fucosylated trimannose

N-glycan, towards immunoglobulin G has been also reported in SLE patients

[42][61]. The increased exposure of mannose residues in IgG facilitates the activation of FcγRIIIa and increases antibody-mediated cytotoxicity

[43][53]. These mannose-exposed glycans have few fucose residues, which may also affect FcγRIIIa binding; in addition, mannose-binding lectin (MBL) can recognize these mannose-exposed glycans in IgG and activate the complement lectin pathway

[43][53].

Endoglycosidase S is an enzyme that cleaves the

N-glycans of IgG, but not those of IgM, exposing an

N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) from the glycosidic core and its branched fucose residue. Treatment of BXSB mice that developed a lupus-like disease with endoglycosidase S did not reduce anti-dsDNA (double-stranded) or antinuclear antibody levels, but increased mouse survival and improved blood urea levels

[45][71]. The proposed mechanism is that treatment with endoglycosidase S reduces the affinity of antibodies towards FcγR, which could prevent activation by immune complexes

[46][72].

In the case of SLE patients, using ultra-resolution liquid chromatography, it was found that they present a decrease in IgG galactosylation and sialylation; a decrease in the fucose nucleus and an increase in

N-acetylglucosamine bisector was also observed. These glycosylation abnormalities were associated with pericarditis, proteinuria, and the presence of antinuclear antibodies

[47][73].

5.1.2. Glycosylation of Variable Regions

The wide variety of antibodies with different affinities is due to the rearrangement of the variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments, as well as somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination. During somatic hypermutation, point mutations occur in the variable regions of the heavy and light chains of immunoglobulins. These mutations can generate consensus sequences for

N-glycosylation. The glycans attached to these sequences are called Fab glycans. It is estimated that 15% of IgGs have

N-glycosylations in the variable regions, mainly as a result of hypermutation

[48][49][75,76]. The function of these

N-glycans is to regulate the affinity and stability of the antigen–antibody bond, as well as to prolong the half-life of the antibodies

[40][41][50][68,69,77].

5.2. Alterations in the Glycosylation of the T Cells in SLE

It has been shown that T cells from SLE patients present alterations in

O-glycosylation

[51][62] using the

Amaranthus leucocarpus lectin (ALL), which recognizes core 1 in coactivating T cell receptors

[52][82]. T cells from patients with active SLE had less recognition by ALL than those with inactive SLE, and expression of receptors recognized by ALL was inversely correlated with disease activity

[51][62].

Alterations in the expression of core 1 have also been described in murine models of lupus. T cells from MLR-lpr mice show reduced recognition of

Maclura pomifera lectin compared to T cells from MLR++ mice

[53][58]. The

Maclura pomifera lectin is a Tn antigen-specific lectin

[54][83]. MLR-lpr mice develop the disease faster and with greater clinical manifestations than MLR++ mice (Richard and Gilkeson, 2018), and show decreased

O-glycosylation of their T cells similar to that seen in patients with active SLE

[51][62].

Other lectins that recognize

O-glycans, such as the

Arachis hypogaea lectin or

Peanut Agglutinin (PNA) and the

Artocarpus integrifolia lectin (Jacalin), have not shown alterations in

O-glycosylation in T cells from SLE patients

[51][62]. These discrepancies may be due to the type of lectin used, since despite recognizing the same sugar, their affinity is variable and they recognize sugars present in different proteins

[55][56][86,87].

6. Alterations in Cytoplasmic O-GlcNAcylation

O-linked

N-acetylglucosamine (

O-GlcNAcylation) is a post-translational modification in which the monosaccharide

N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNA) is added to serine or threonine residues of cytoplasmic or nuclear proteins. This transfer is mediated by

O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and can be removed by

O-GlcNAcase (OGA). Unlike the other types of glycosylation previously discussed,

O-GlcNAcylation does not occur in the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus, but rather in the cytosol. The addition of this monosaccharide to proteins has effects on protein localization, stability, and interactions

[57][97].

O-GlcNAcylation regulates immune system functions such as inflammatory and antiviral responses in macrophages

[58][98], promotes activated neutrophils functions

[59][99], and inhibits natural killer cell activity

[57][60][97,100].

A decrease in

O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of E74-like factor 1 (ELF-1) has been observed in SLE patients. ELF-1 is a transcriptional factor that binds to the promoter of the gene that encodes the zeta (ζ) chain of the CD3 molecule, thereby increasing its transcription. For this interaction to occur, the ELF-1 factor must be glycosylated and phosphorylated, constituting the 98 KDa isoform. Decreased glycosylation and phosphorylation of ELF-1 cause a decrease in its binding to DNA and a decrease in CD3ζ expression

[61][101].

The decrease in

O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of E74-like factor 1 (ELF-1) is consistent with decreased expression of CD3ζ mRNA and its protein in SLE patients. To compensate for CD3ζ deficiency, the T-cell receptor complex associates with the Fc receptor gamma chain (FcRγ), causing alterations in intracellular signaling pathways as well as increased phosphorylation of tyrosine residues, an increase in the concentration of cytoplasmic calcium, and low production of IL-2

[62][63][102,103].