Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) is the cornerstone of treating advanced ovarian cancer. Approximately 60–70% of patients with advanced ovarian cancer will have involvement in the upper abdomen or the supracolic compartment of the abdominal cavity. Though the involvement of this region results in poorer survival compared, complete cytoreduction benefits overall survival, making upper-abdominal cytoreduction an essential component of CRS for advanced ovarian cancer. The upper abdomen constitutes several vital organs and large blood vessels draped with the parietal or visceral peritoneum, common sites of disease in ovarian cancer. A surgeon treating advanced ovarian cancer should be well versed in upper-abdominal cytoreduction techniques, including diaphragmatic peritonectomy and diaphragm resection, lesser omentectomy, splenectomy with or without distal pancreatectomy, liver resection, cholecystectomy, and suprarenal retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Other procedures such as clearance of the periportal region, Glisson’s capsulectomy, clearance of the superior recess of the lesser sac, and Morrison’s pouch are essential as these regions are often involved in ovarian cancer.

- advanced ovarian cancer

- cytoreductive surgery

- upper-abdominal surgery

1. Introduction

2. Surgical Anatomy of the Upper Abdomen

2.1. Peritoneal Ligaments and Spaces

2.2. Anatomical Boundaries from the Surgical Viewpoint

| Region | Peritoneal Region | Boundaries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Right subphrenic peritoneum | From the right of the falciform ligament medially, it includes all the peritoneum the under the surface of the right dome, extending inferiorly to the lower pole of the right kidney [16]. Postero-superiorly, it merges with Glisson’s capsule at the superior boundary of the right lobe. The coronary or right triangular ligament has to be divided completely to excise this part of the peritoneum. Postero-medially it is attached to the posteromedial edge of segments 6 and 7. Division of this attachment exposes the retrohepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) [17]. Medially, it follows the inferior edge of segments 5 and 6 to the lateral edge of the porta hepatis and includes the peritoneum on the second and third parts of the duodenum. The sub-hepatic region is Morrison’s pouch, as described below. | From the right of the falciform ligament medially, it includes all the peritoneum the under the surface of the right dome, extending inferiorly to the lower pole of the right kidney [43]. Postero-superiorly, it merges with Glisson’s capsule at the superior boundary of the right lobe. The coronary or right triangular ligament has to be divided completely to excise this part of the peritoneum. Postero-medially it is attached to the posteromedial edge of segments 6 and 7. Division of this attachment exposes the retrohepatic inferior vena cava (IVC) [44]. Medially, it follows the inferior edge of segments 5 and 6 to the lateral edge of the porta hepatis and includes the peritoneum on the second and third parts of the duodenum. The sub-hepatic region is Morrison’s pouch, as described below. |

| Morrisons’ pouch | This is the right sub-hepatic space that extends laterally from the medial boundary of the right kidney [16]. It is bounded superiorly by the inferior surface of segments 5 and 6, medially by the lateral edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament, inferiorly, the superior and lateral edge of the duodenum, and inferolaterally, the hepatic flexure. It merges laterally with the right subphrenic peritoneum [17]. | This is the right sub-hepatic space that extends laterally from the medial boundary of the right kidney [43]. It is bounded superiorly by the inferior surface of segments 5 and 6, medially by the lateral edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament, inferiorly, the superior and lateral edge of the duodenum, and inferolaterally, the hepatic flexure. It merges laterally with the right subphrenic peritoneum [44]. | |

| Right Glisson’s capsule | Capsule of the right lobe of the liver (superior and lateral surfaces). Extends from the right side of the falciform’s attachment onto the right lobe’s superior surface and the lateral surface, merging with the attachment of the right subphrenic peritoneum to the liver in that region. | ||

| Right inferior Glisson’s capsule | The part of the capsule on the inferior surface of the right lobe and the right caudate lobe. | ||

| Foramen of Winslow | The foramen of Winslow, also known as the omental foramen, epiploic foramen and foramen epiploicum (Latin), is a foramen connecting the greater sac or the general cavity (of the abdomen), and the lesser sac, the omental bursa. It is bounded by the free edge of the lesser omentum anteriorly that contains the common bile duct, the hepatic artery and the portal vein; the peritoneum covering the anterior surface of the inferior vena cava posteriorly; the peritoneum covering the caudate lobe superiorly; and the peritoneum covering the first part of the duodenum inferiorly. | ||

| 2 | Falciform ligament | It is a fold of fibrofatty tissue extending from the umbilicus along the inferior surface of the anterior abdominal wall to the diaphragm. Inferiorly, it forms the umbilical round ligament in the umbilical fissure containing the obliterated umbilical vein. | |

| Tissue in the umbilical fissure | This is a band of tissue containing the obliterated umbilical vein that merges superiorly with the falciform ligament and inferiorly with the hepatoduodenal ligament. | ||

| Left central diaphragmatic peritoneum- | From the left edge of the falciform ligament till the left lateral boundary of the esophageal hiatus and inferiorly, it merges with the peritoneal reflection on the superior edge of the left lobe of the liver. | ||

| Left Glisson’s capsule- | Capsule on the superior and inferolateral surface of the left lobe that lies to the left of the falciform ligament | ||

| Hepatoduodenal ligament | This is the peritoneum overlying the porta hepatis extending from the lateral border of the common bile duct to the medial border of the portal vein and the lower end of the umbilical ligament to the superior border of the first part of the duodenum. The common bile duct, the hepatic artery, and the portal vein are encased in this peritoneal fold. | ||

| Lesser omentum | The lesser omentum extends from the medial boundary of the hepatoduodenal ligament inferiorly to the left coronary ligament superiorly. It is attached inferomedially to the lesser curve and superiorly to the inferior surface of the left lobe overhanging the caudate. The left coronary ligament must be divided completely to excise the lesser omentum. The gastric arcade is preserved without gross tumor deposits in this region. | ||

| Lesser sac superior recess | This is part of the lesser sac lying superior to the left coronary ligament. The caudate lobe is reflected laterally to expose this region. This region is bounded by the IVC laterally, and the lesser curve medially, and its floor is formed by the IVC and the right crus of the diaphragm. Superiorly it merges with the central diaphragmatic peritoneum. | ||

| Lesser sac inferior recess | This includes the anterior leaf of the transverse mesocolon, the pancreatic capsule, and the gastro-pancreatic fold of the peritoneum. The capsule is removed over the entire pancreas, head, body, and tail. | ||

| 3 | Left subphrenic peritoneum | Extends from the midline anteriorly to the left lateral side to include all the peritoneum on the undersurface of the left dome of the diaphragm, merging postero-inferiorly with the upper end of the left antero-parietal peritoneum, superomedially the lateral edge of the abdominal esophagus and fundus, and along the lateral edge of the spleen inferomedially. Removal of the peritoneum from the spleen should extend right up to the hilum posteriorly and expose the splenic hilar vessels. |

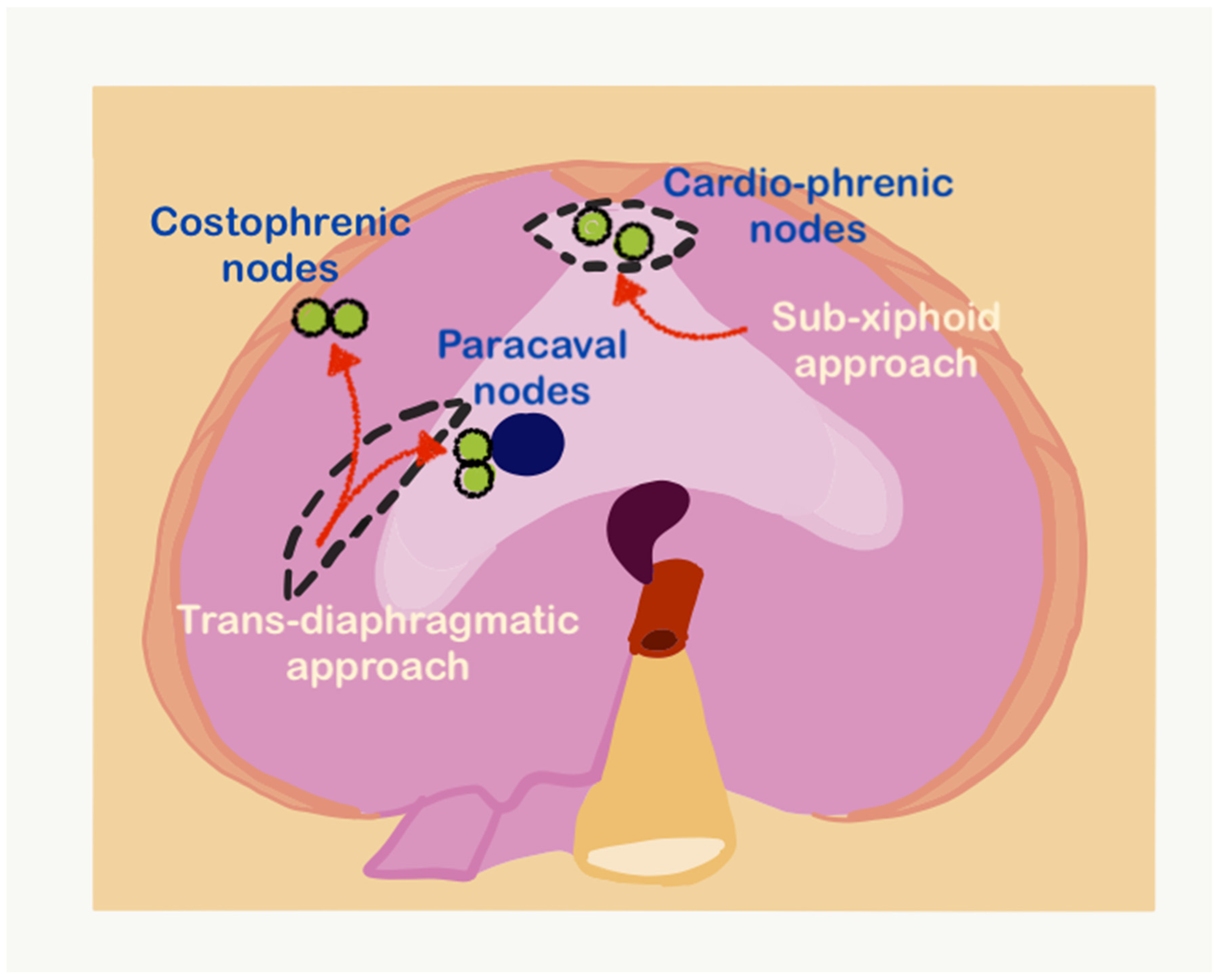

2.3. Regional Nodes