The clinical translation of messenger mRNA (mRNA)-based therapeutics requires safe and effective delivery systems. Although considerable progress has been made on the development of mRNA delivery systems, many challenges, such as the dose-limiting toxicity and specific delivery to extrahepatic tissues, still remain. Cell-derived vesicles, a type of endogenous membranous particle secreted from living cells, can be leveraged to load mRNA during or after their biogenesis. They have received increasing interest for mRNA delivery due to their natural origin, good biocompatibility, cell-specific tropism, and unique ability to cross physiological barriers.

- cell-derived vesicles

- extracellular vesicles

- exosome

- mRNA delivery

1. Introduction

2. Preparation of Cell-Derived Vesicles

Commonly, EVs with or without mRNA cargos should be produced firstly from the producer cells for further isolation and purification. Several types of cells have been explored as source cells of EVs, such as red blood cells, human embryonic kidney 293T cells, bone marrow-derived dendritic cells, and Gram-negative bacteria [25][26][27][28][29]. For EV-based mRNA delivery, 293T were the mostly commonly used cells, accounting for about 80% in all source cells. Following secretion, multiple techniques such as ultra-centrifugation, density gradient centrifugation, size exclusion chromatography, and filtration methods have been exploited to obtain purified EVs from source cells [30][31][32][33]. To boost the capability of exosomes production, potential production boosters including STEAP3, syndecan-4, and a fragment of L-aspartate oxidase were employed [34]. STEAP3 and L-aspartate oxidase-related fragment involve the biogenesis and cellular metabolism of exosomes, while syndecan-4 contributes to the inward budding of early endosomes membranes [34]. Co-overexpression of all three boosters in 293T cells significantly increased exosome production [34]. Apart from production boosters, cellular nanoporation (CNP) consisting of a nanochannel array (~500 nm in diameter) has also been proposed for increasing the production of mRNA-loaded exosomes via transient electrical pulses [35]. The yield of mRNA-bearing exosomes for CNP was more than 50-fold higher in comparison with the traditional electroporation method [35]. Furthermore, abundant EVs (1013–1014 EVs) were produced by treating red blood cells with calcium ionophore [36]. It is worth noting that the heterogeneity of EVs resulted from the process of production and separation has an important impact on their delivery efficiency. Thus, thorough characterization of EVs, including the particle size, zeta potential, morphologies, and surface markers, is necessary for subsequent quality control and biomedical applications [30][32][37][38].3. Strategies for mRNA Loading into Cell-Derived Vesicles

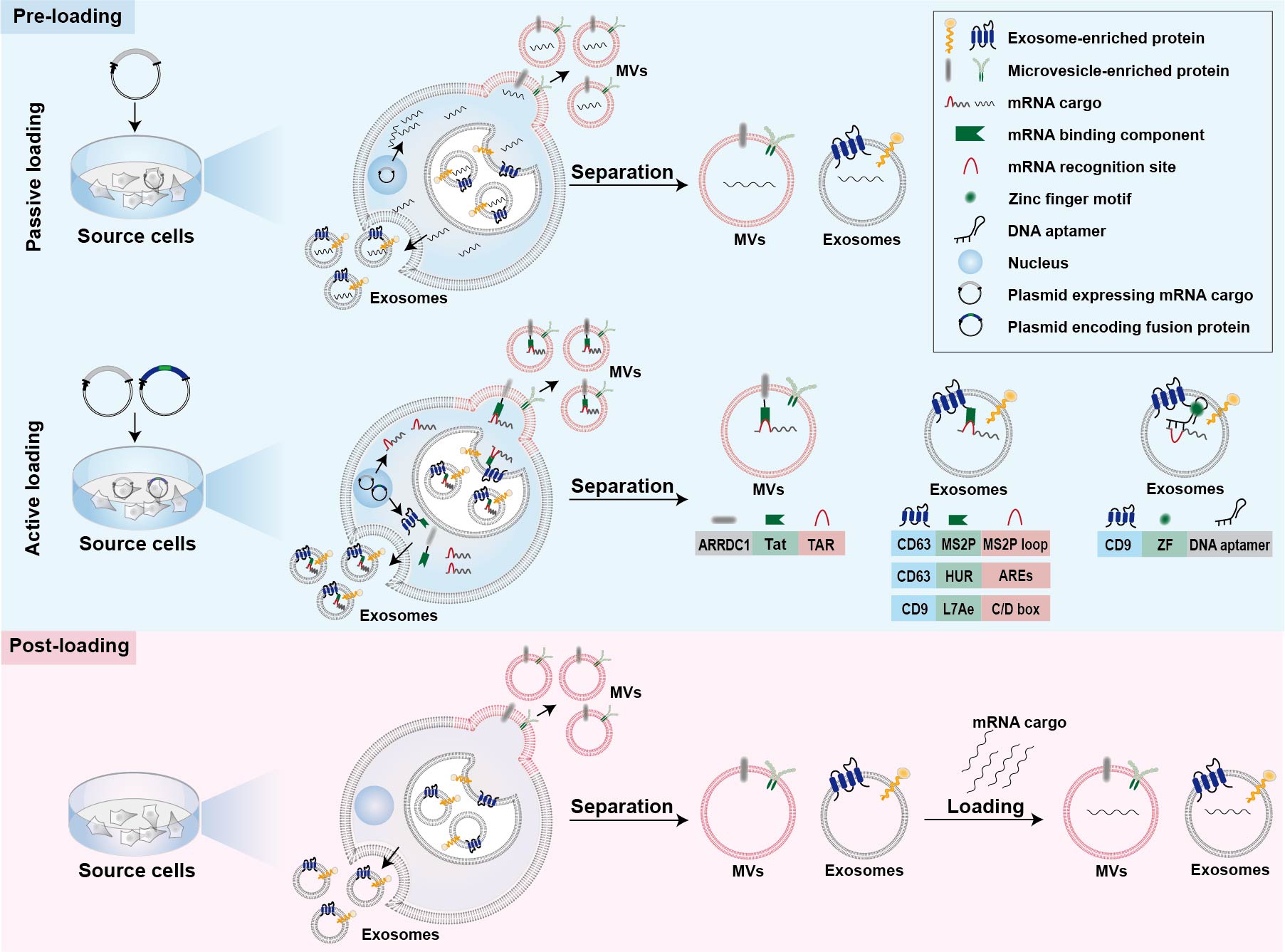

Strategies for mRNA loading into cell-derived vesicles could be simply classified into two main categories, namely pre-loading methods and post-loading methods (Figure 1) [39][40]. Pre-loading methods (also called pre-separation or endogenous loading methods) heavily rely on the producer cells to pack the mRNA cargos into EVs during their biogenesis (Figure 1) [40]. Sometimes, mRNA-encoded proteins are also simultaneously packaged into cell-derived vesicles during the endogenous loading process [41][42]. Pre-loading methods can be further divided into passive and active categories as described below (Figure 1) [43]. Post-loading methods are also called post-separation or exogenous loading methods [40]. In this case, exogenous mRNA is loaded into isolated EVs via electroporation or chemical transfection reagents (Figure 1) [36][44].

3.1. Passive Pre-Loading Methods

The most common approach for passive pre-loading methods is to introduce plasmid into producer cells to obtain the transcribed mRNA of interest. Overexpression of target mRNA could facilitate its enrichment into EVs. Such strategy has been employed by several studies for loading various mRNA into EVs [42][45][46]. For example, low-density lipoprotein receptor (Ldlr) mRNA was encapsulated into exosomes via forced overexpression in the source cells [46]. After plasmid transfection, the level of Ldlr mRNA in source cells increased more than 100-fold compared with cells transfected with control plasmid, thus leading to a similar increase in mRNA cargos in the secreted exosomes [46]. Because small RNAs are the dominant modalities of RNAs within secreted exosomes, encapsulation of large mRNA into nano-sized exosomes is technically challenging for passive pre-loading method [39][47]. It is revealed that the aforementioned CNP technology not only increases the yield of exosomes but also improves mRNA content in the exosomes [35]. In comparison with exosomes produced endogenously without external stimulation, the mRNA loading efficiency of CNP-treated exosomes produced by the same source cells increased by three or four orders of magnitude (one mRNA within every 103 exosomes vs. two to ten mRNA per exosome) [35]. Additionally, this strategy also led to a 100-folded higher loading of mRNA into exosomes relative to conventional electroporation method [35].3.2. Active Pre-Loading Methods

Another strategy to improve the loading efficiency of mRNA cargos is to transfect the producer cells with two types of plasmid. One type of the plasmid encodes fusion proteins comprised of mRNA binding components and EV-enriched proteins such as surface markers CD9, CD63, or cytosolic protein Hspa8 [34][43][48]. Generally speaking, the mRNA of interest transcribed from plasmids contains intentionally engineered recognition sites, which can specifically bind with the mRNA binding components of fusion proteins. The remaining part of the fusion proteins, EV-enriched proteins, are then incorporated into EVs during their biogenesis to achieve active mRNA pre-loading. Targeted and Modular EV loading (TAMEL) is an active loading platform developed for actively loading mRNA into exosomes via fusing a EV-enriched protein such as Lamp2b, CD63, and Hspa8 to the MS2 bacteriophage coat protein [43]. The cognate MS2 stem loop sequence was then incorporated into the mRNA cargos to promote mRNA binding and loading into the EVs interior [43]. It has been found that the loading efficiency decreases with the increase in mRNA size [43]. Several other fusion proteins have also been designed for active loading of mRNA into EVs [34][48]. Archaeal ribosomal protein L7Ae or human antigen R fused to surface marker of EVs are leveraged to bind to the introduced C/D box RNA structure and AU-rich elements in the mRNA cargos, respectively [34][48]. In addition, fusing the transactivator of the transcription protein to the C-terminus of arrestin domain containing protein 1, which mediated the budding of MVs, confers high affinity for binding the stem-loop-containing trans-activating response element introduced at the 5′ end of mRNA cargos [49]. In general, the high binding affinity between mRNA binding components and mRNA recognition site facilitates the active packaging of specific mRNA into EVs. Apart from these mRNA binding components, DNA aptamer was also used to specifically recognize and actively load the mRNA of interest [50]. In this case, a specific DNA aptamer consisting of two parts was designed as a bridge for connection between mRNA cargos and EVs [50]. The single strand part of the DNA aptamer could recognize the region surrounding start codon AUG of target mRNA, which was thought to be beneficial for the sorting of mRNA into EVs [50]. The double strand part of the DNA aptamer could be recognized by zinc finger motifs (ZF) that were tailored to specifically bind to the sequence of any double-stranded DNA [50]. To facilitate the recruit of DNA aptamer as well as sorting of the complexed mRNA into EVs, the ZF was fused with an exosomal surface marker, CD9 [50]. As a result, this designed DNA aptamer resulted in a ~2.5-fold increase in the enrichment effect of large PGC1α mRNA into EVs [50].3.3. Post-Loading Methods

So far, post-loading mRNA into EVs largely depends on electroporation and commercial loading reagents. Electroporation is a commonly used method for loading of various molecules, including siRNA and miRNA, as well as mRNA, to purified EVs [36][51][52][53][54]. About one fifth of Cas9 mRNA can be loaded into red blood cell-derived EVs by electroporation [36]. Furthermore, a commercial loading reagent named REG1 has also been used for loading mRNA into EVs after their isolation [44].4. Strategies for Tissue-Specific mRNA Expression

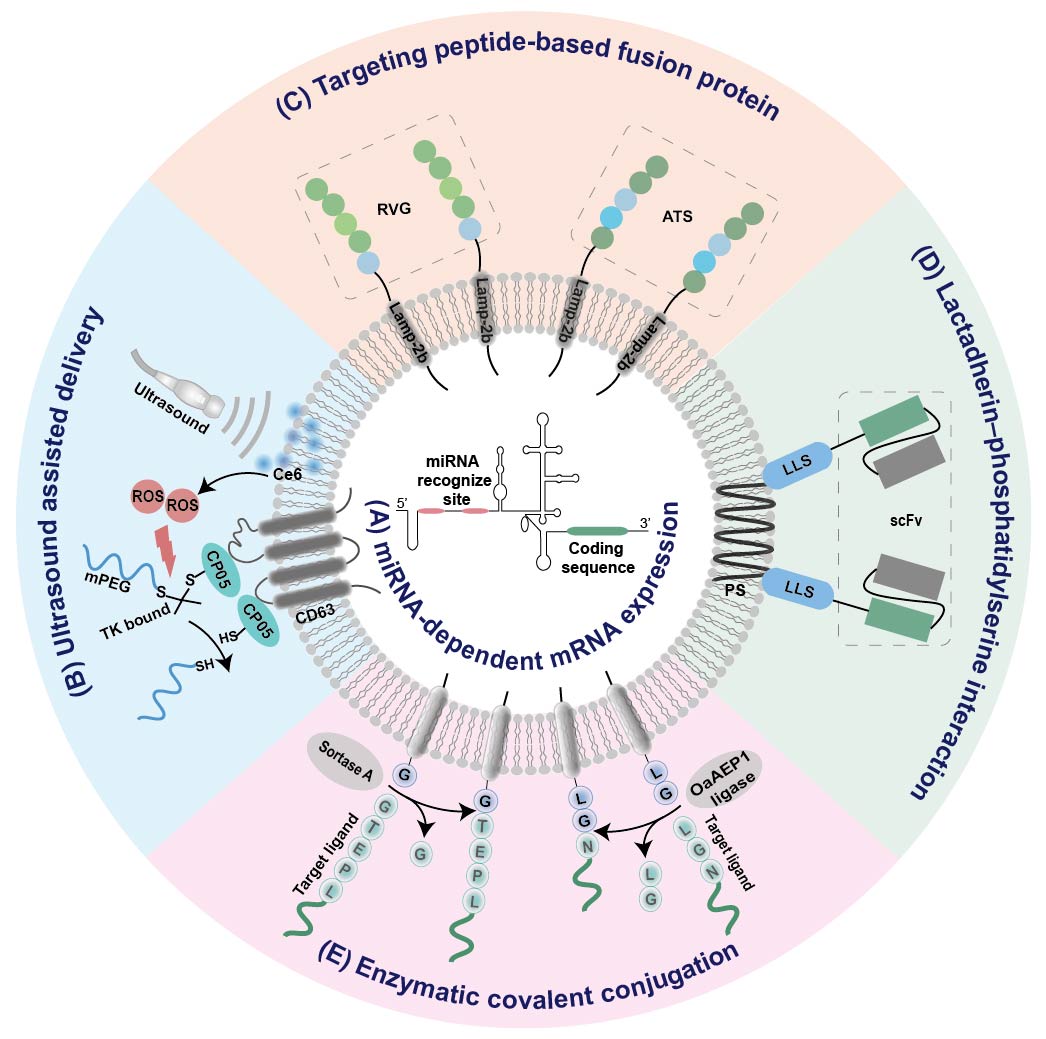

Figure 2. Summary of EV-based platforms for tissue-specific mRNA expression. (A) miRNA-dependent mRNA expression. (B) Ultrasound assisted delivery. (C) Targeting peptide-based fusion protein. (D) Lactadherin–phosphatidylserine interaction. (E) Enzymatic covalent conjugation. IRES internal ribosome entry site; RVG, rabies viral glycoprotein; ATS, adipocyte-targeting sequence scFv, single chain variable fragment; LLS, lactadherin leader sequence; Ce6, sonosensitizer chlorin e6; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PS, phosphatidylserine;

Figure 2. Summary of EV-based platforms for tissue-specific mRNA expression. (A) miRNA-dependent mRNA expression. (B) Ultrasound assisted delivery. (C) Targeting peptide-based fusion protein. (D) Lactadherin–phosphatidylserine interaction. (E) Enzymatic covalent conjugation. IRES internal ribosome entry site; RVG, rabies viral glycoprotein; ATS, adipocyte-targeting sequence scFv, single chain variable fragment; LLS, lactadherin leader sequence; Ce6, sonosensitizer chlorin e6; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PS, phosphatidylserine;

4.1. Tissue-Specific miRNA-Dependent mRNA Expression

It has been found that the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) at the 5′ end of the hepatitis C virus RNA can be specifically recognized by liver-specific miRNA-122, and thus initiates its tissue-specific mRNA translation [55]. Replacement of this miR-122 recognition site at the IRES with sequences recognized by other tissue-specific miRNA enables miRNA-specific activation of mRNA translation in specific tissues (Figure 2A). According to this principle, an adipose-specific translation system (miR-148a-IRES-PGC1α) was constructed by substituting miR-122 recognition sites at the IRES with sequences recognized by adipose-specific miR-148a at the upstream of the PGC1α mRNA coding sequence [56]. Injection of exosome loading with such a system resulted in a significant increase in PGC1α protein expression in the adipose tissue of mice, but a decrease in lung, spleen, and kidney [56]. Using a similar strategy, the same group also constructed inflammation-responsive Il-10 mRNA by replacing miR-122 with miR-155 enriched in the inflammatory sites of atherosclerosis [45]. The expression of Il-10 mRNA in exosomes was specifically activated by miR-155 in the inflamed macrophages, while its expression in other tissues without obvious inflammation was rare [45].

Figure 2. Summary of EV-based platforms for tissue-specific mRNA expression. (A) miRNA-dependent mRNA expression. (B) Ultrasound assisted delivery. (C) Targeting peptide-based fusion protein. (D) Lactadherin–phosphatidylserine interaction. (E) Enzymatic covalent conjugation. IRES internal ribosome entry site; RVG, rabies viral glycoprotein; ATS, adipocyte-targeting sequence scFv, single chain variable fragment; LLS, lactadherin leader sequence; Ce6, sonosensitizer chlorin e6; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PS, phosphatidylserine;

4.2. Ultrasound Assisted Tissue-Specific Delivery

To minimize the off-target effects, exosomal delivery strategies assisted by ultrasound have been explored (Figure 2B) [56][57]. Recently, two ultrasound-assisted exosomal platforms have been established for the specific delivery of mRNA to adipose tissue [56][57]. In one study, target uptake of EVs was achieved with the assistance of ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction (UTMD) as well as the tissue-specific miRNA-dependent expression system mentioned above [56]. As the microbubble destruction at the ultrasound site may enhance the cell membrane permeability and cellular uptake of recipient cells, the delivery of exosomes into the adipose tissue should be increased by UTMD. Consistent with this assumption, the distribution of DiR-labeled exosomes in the adipose tissue significantly increased under the assistance of UTMD [56]. In the other study, a smart exosome-based delivery platform was designed for escaping from phagocytosis and locally delivering mRNA to the omental adipose tissue (Figure 2B) [57]. Firstly, CP05-thioketal (TK)-mPEG was anchored onto exosomes through interaction between the peptide CP05 and the CD63 marker of exosomes [57]. The mPEG chain could protect the carrier platform from aggregation, opsonization, and phagocytosis, thus prolonging the in vivo circulation time [57]. Then, reactive oxygen species produced by sonosensitizer chlorin e6 under ultrasound triggered the break of TK bonds between CP05 and mPEG [57]. Eventually, the carrier core was exposed by removing the PEG corona and specifically internalized by recipient cells at the ultrasound site, thus leading to a dramatic increase in the expression of exosome-encapsulated mRNA in adipose tissue under ultrasound [57].4.3. Targeted Modification

Conjugation of targeting ligands to EVs via genetic engineering, enzymatic, or affinity-based methods was proven to be effective for exosome-based targeted delivery [58][59][60][61]. For example, when the central nervous system-specific rabies viral glycoprotein (RVG) was fused to an exosomal membrane protein Lamp2b, the fusion protein RVG-Lamp2b facilitated transport of EVs across the blood–brain barrier (Figure 2C) [34][42]. To fulfill the targeted delivery of EVs to adipose tissues, an adipocyte-targeting sequence (ATS, CKGGRAKDC) was also fused to the N-terminus of Lamp2b (Figure 2C) [50]. Moreover, an anti-HER2 single chain variable fragment was connected to a lactadherin leader sequence (Figure 2D) [62]. The former was capable of targeting HER2 overexpressing cells via antigen–antibody interactions, while the latter could bind to EVs based on affinity with their surface phosphatidylserine [62]. As a consequence, the modified EVs were selectively internalized by HER2-positive cells [62]. Despite its straightforwardness, the fusion protein-based targeting method always require genetic engineering. Therefore, covalently conjugating peptides or nanobodies onto EVs without any genetic modification of source cells provide an alternative method for the targeted modification of EVs (Figure 2E) [44]. The versatile targeting platform leverages protein-ligating enzymes (Sortase A and OaAEP1 ligase) to catalyze covalent-bonding reactions between the membrane proteins of EVs and targeting ligands, including targeting peptides, ‘self’ peptides, as well as nanobodies [44].References

- Cobb, M. Who discovered messenger RNA? Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, R526–R532.

- Dammes, N.; Peer, D. Paving the Road for RNA Therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 755–775.

- Boo, S.H.; Kim, Y.K. The emerging role of RNA modifications in the regulation of mRNA stability. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 400–408.

- Sahin, U.; Karikó, K.; Türeci, Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics--developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 759–780.

- Xiao, Y.; Tang, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Kong, N.; Tao, W. Emerging mRNA technologies: Delivery strategies and biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 3828–3845.

- Paunovska, K.; Loughrey, D.; Dahlman, J.E. Drug delivery systems for RNA therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 265–280.

- Ibba, M.L.; Ciccone, G.; Esposito, C.L.; Catuogno, S.; Giangrande, P.H. Advances in mRNA non-viral delivery approaches. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 177, 113930.

- Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y. Nanoscale platforms for messenger RNA delivery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 11, e1530.

- Barbier, A.J.; Jiang, A.Y.; Zhang, P.; Wooster, R.; Anderson, D.G. The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 840–854.

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines—A new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 261–279.

- Beck, J.D.; Reidenbach, D.; Salomon, N.; Sahin, U.; Türeci, Ö.; Vormehr, M.; Kranz, L.M. mRNA therapeutics in cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 69.

- Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, B. Nonviral Delivery of CRISPR/Cas Systems in mRNA Format. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2022, 2, 2200082.

- Qiu, M.; Li, Y.; Bloomer, H.; Xu, Q. Developing Biodegradable Lipid Nanoparticles for Intracellular mRNA Delivery and Genome Editing. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 4001–4011.

- Huang, X.; Kong, N.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Langer, R.; Tao, W. The landscape of mRNA nanomedicine. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2273–2287.

- Patel, S.; Ashwanikumar, N.; Robinson, E.; Xia, Y.; Mihai, C.; Griffith, J.P., 3rd; Hou, S.; Esposito, A.A.; Ketova, T.; Welsher, K.; et al. Naturally-occurring cholesterol analogues in lipid nanoparticles induce polymorphic shape and enhance intracellular delivery of mRNA. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 983.

- Liu, S.; Cheng, Q.; Wei, T.; Yu, X.; Johnson, L.T.; Farbiak, L.; Siegwart, D.J. Membrane-destabilizing ionizable phospholipids for organ-selective mRNA delivery and CRISPR-Cas gene editing. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 701–710.

- Li, M.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, W.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, B.; Li, B. Secreted Expression of mRNA-Encoded Truncated ACE2 Variants for SARS-CoV-2 via Lipid-Like Nanoassemblies. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2101707.

- Ren, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, S. Self-assembled polymeric micelle as a novel mRNA delivery carrier. J. Control. Release 2021, 338, 537–547.

- Hou, X.; Zaks, T.; Langer, R.; Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 1078–1094.

- Eygeris, Y.; Gupta, M.; Kim, J.; Sahay, G. Chemistry of Lipid Nanoparticles for RNA Delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2–12.

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, C.; Jankovic, K.E.; Dong, Y. Lipids and Lipid Derivatives for RNA Delivery. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12181–12277.

- Dowdy, S.F. Overcoming cellular barriers for RNA therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 222–229.

- Loughrey, D.; Dahlman, J.E. Non-liver mRNA Delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 13–23.

- Cheng, Q.; Wei, T.; Farbiak, L.; Johnson, L.T.; Dilliard, S.A.; Siegwart, D.J. Selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles for tissue-specific mRNA delivery and CRISPR-Cas gene editing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 313–320.

- Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, K.; Feng, Q.; Ma, N.; Liang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, L.; et al. Nie, Rapid Surface Display of mRNA Antigens by Bacteria-Derived Outer Membrane Vesicles for a Personalized Tumor Vaccine. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2109984.

- Meng, W.; He, C.; Hao, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Zhu, G. Prospects and challenges of extracellular vesicle-based drug delivery system: Considering cell source. Drug Deliv. 2020, 27, 585–598.

- Grange, C.; Skovronova, R.; Marabese, F.; Bussolati, B. Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Kidney Regeneration. Cells 2019, 8, 1240.

- Veerman, R.E.; Akpinar, G.G.; Eldh, M.; Gabrielsson, S. Immune Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles—Functions and Therapeutic Applications. Trends Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 382–394.

- Hade, M.D.; Suire, C.N.; Suo, Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Applications in Regenerative Medicine. Cells 2021, 10, 1959.

- Buschmann, D.; Mussack, V.; Byrd, J.B. Separation, characterization, and standardization of extracellular vesicles for drug delivery applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 174, 348–368.

- Jia, Y.; Yu, L.; Ma, T.; Xu, W.; Qian, H.; Sun, Y.; Shi, H. Small extracellular vesicles isolation and separation: Current techniques, pending questions and clinical applications. Theranostics 2022, 12, 6548–6575.

- Alzhrani, G.N.; Alanazi, S.T.; Alsharif, S.Y.; Albalawi, A.M.; Alsharif, A.A.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.S.; Elsherbiny, N. Exosomes: Isolation, characterization, and biomedical applications. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 1807–1831.

- Chen, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Du, L. Review on Strategies and Technologies for Exosome Isolation and Purification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 811971.

- Kojima, R.; Bojar, D.; Rizzi, G.; Hamri, G.C.; El-Baba, M.D.; Saxena, P.; Ausländer, S.; Tan, K.R.; Fussenegger, M. Designer exosomes produced by implanted cells intracerebrally deliver therapeutic cargo for Parkinson’s disease treatment. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1305.

- Yang, Z.; Shi, J.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, T.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Large-scale generation of functional mRNA-encapsulating exosomes via cellular nanoporation. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 69–83.

- Usman, W.M.; Pham, T.C.; Kwok, Y.Y.; Vu, L.T.; Ma, V.; Peng, B.; Chan, Y.S.; Wei, L.; Chin, S.M.; Azad, A.; et al. Efficient RNA drug delivery using red blood cell extracellular vesicles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2359.

- Lai, J.J.; Chau, Z.L.; Chen, S.Y.; Hill, J.J.; Korpany, K.V.; Liang, N.W.; Lin, L.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Liu, J.K.; Liu, Y.C.; et al. Exosome Processing and Characterization Approaches for Research and Technology Development. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2103222.

- Coumans, F.A.W.; Brisson, A.R.; Buzas, E.I.; Dignat-George, F.; Drees, E.E.E.; El-Andaloussi, S.; Emanueli, C.; Gasecka, A.; Hendrix, A.; Hill, A.F.; et al. Methodological Guidelines to Study Extracellular Vesicles. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1632–1648.

- O’Brien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 585–606.

- Schulz-Siegmund, M.; Aigner, A. Nucleic acid delivery with extracellular vesicles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 173, 89–111.

- Mizrak, A.; Bolukbasi, M.F.; Ozdener, G.B.; Brenner, G.J.; Madlener, S.; Erkan, E.P.; Ströbel, T.; Breakefield, X.O.; Saydam, O. Genetically engineered microvesicles carrying suicide mRNA/protein inhibit schwannoma tumor growth. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 101–108.

- Yang, J.; Wu, S.; Hou, L.; Zhu, D.; Yin, S.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y. Therapeutic Effects of Simultaneous Delivery of Nerve Growth Factor mRNA and Protein via Exosomes on Cerebral Ischemia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 21, 512–522.

- Hung, M.E.; Leonard, J.N. A platform for actively loading cargo RNA to elucidate limiting steps in EV-mediated delivery. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2016, 5, 31027.

- Pham, T.C.; Jayasinghe, M.K.; Pham, T.T.; Yang, Y.; Wei, L.; Usman, W.M.; Chen, H.; Pirisinu, M.; Gong, J.; Kim, S.; et al. Covalent conjugation of extracellular vesicles with peptides and nanobodies for targeted therapeutic delivery. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12057.

- Bu, T.; Li, Z.; Hou, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, L.; Wei, M.; Yang, G.; Yuan, L. Exosome-mediated delivery of inflammation-responsive Il-10 mRNA for controlled atherosclerosis treatment. Theranostics 2021, 11, 9988–10000.

- Li, Z.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Yuan, L. Exosome-based Ldlr gene therapy for familial hypercholesterolemia in a mouse model. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2953–2965.

- Tang, T.T.; Wang, B.; Lv, L.L.; Dong, Z.; Liu, B.C. Extracellular vesicles for renal therapeutics: State of the art and future perspective. J. Control. Release 2022, 349, 32–50.

- Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wei, M.; Gao, X.; Zhao, L.; Shi, R.; Sun, W.; Duan, Y.; Yang, G.; Yuan, L. In Vitro and in Vivo RNA Inhibition by CD9-HuR Functionalized Exosomes Encapsulated with miRNA or CRISPR/dCas9. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 19–28.

- Wang, Q.; Yu, J.; Kadungure, T.; Beyene, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Q. ARMMs as a versatile platform for intracellular delivery of macromolecules. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 960.

- Zhang, S.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Wei, M.; Yuan, L.; Yang, G. Selective Encapsulation of Therapeutic mRNA in Engineered Extracellular Vesicles by DNA Aptamer. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 8563–8570.

- Popowski, K.D.; Abad, B.L.d.J.; George, A.; Silkstone, D.; Belcher, E.; Chung, J.; Ghodsi, A.; Lutz, H.; Davenport, J.; Flanagan, M.; et al. Inhalable exosomes outperform liposomes as mRNA and protein drug carriers to the lung. Extracell. Vesicle 2022, 1, 100002.

- Popowski, K.D.; Moatti, A.; Scull, G.; Silkstone, D.; Lutz, H.; de Juan Abad, B.L.; George, A.; Belcher, E.; Zhu, D.; Mei, X.; et al. Inhalable dry powder mRNA vaccines based on extracellular vesicles. Matter 2022, 5, 2960–2974.

- Munir, J.; Yoon, J.K.; Ryu, S. Therapeutic miRNA-Enriched Extracellular Vesicles: Current Approaches and Future Prospects. Cells 2020, 9, 2271.

- Izco, M.; Alvarez-Erviti, L. siRNA Loaded-Exosomes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2282, 395–401.

- Schult, P.; Roth, H.; Adams, R.L.; Mas, C.; Imbert, L.; Orlik, C.; Ruggieri, A.; Pyle, A.M.; Lohmann, V. microRNA-122 amplifies hepatitis C virus translation by shaping the structure of the internal ribosomal entry site. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2613.

- Sun, W.; Xing, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, P.; Yang, G.; Yuan, L. Ultrasound Assisted Exosomal Delivery of Tissue Responsive mRNA for Enhanced Efficacy and Minimized Off-Target Effects. Mol. Nucleic Acids 2020, 20, 558–567.

- Guo, Y.; Wan, Z.; Zhao, P.; Wei, M.; Liu, Y.; Bu, T.; Sun, W.; Li, Z.; Yuan, L. Ultrasound triggered topical delivery of Bmp7 mRNA for white fat browning induction via engineered smart exosomes. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 402.

- Salunkhe, S.; Dheeraj; Basak, M.; Chitkara, D.; Mittal, A. Surface functionalization of exosomes for target-specific delivery and in vivo imaging & tracking: Strategies and significance. J. Control. Release 2020, 326, 599–614.

- Liang, Y.; Duan, L.; Lu, J.; Xia, J. Engineering exosomes for targeted drug delivery. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3183–3195.

- Bashyal, S.; Thapa, C.; Lee, S. Recent progresses in exosome-based systems for targeted drug delivery to the brain. J. Control. Release 2022, 348, 723–744.

- Choi, H.; Yim, H.; Park, C.; Ahn, S.H.; Ahn, Y.; Lee, A.; Yang, H.; Choi, C. Targeted Delivery of Exosomes Armed with Anti-Cancer Therapeutics. Membranes 2022, 12, 85.

- Wang, J.H.; Forterre, A.V.; Zhao, J.; Frimannsson, D.O.; Delcayre, A.; Antes, T.J.; Efron, B.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Pegram, M.D.; Matin, A.C. Anti-HER2 scFv-Directed Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated mRNA-Based Gene Delivery Inhibits Growth of HER2-Positive Human Breast Tumor Xenografts by Prodrug Activation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1133–1142.