The Hox gene cluster, responsible for patterning of the head–tail axis, is an ancestral feature of all bilaterally symmetrical animals (the Bilateria) that remains intact in a wide range of species.

- Hox cluster

- collinearity

- evolution

- axial morphology

- Bilateria

1. Introduction

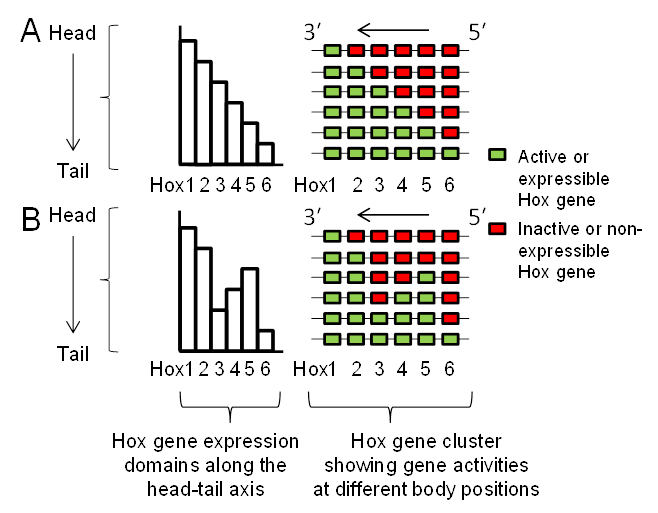

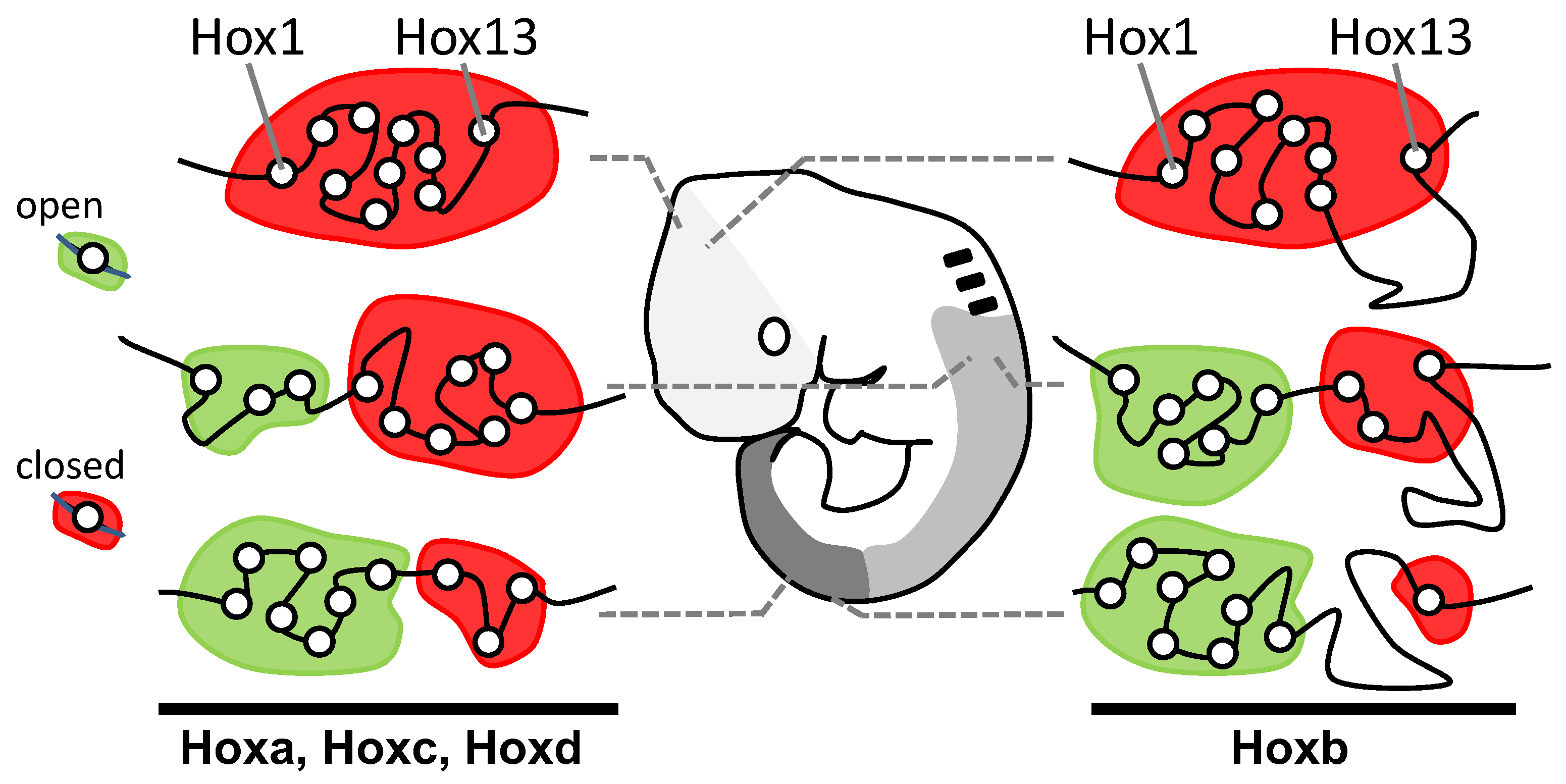

Lewis’s model describes Hox genes as expressing or non-expressing, but researchers now understand that these states are more accurately described as, respectively, expressible or non-expressible. Recent studies in both mice [9][10] and Drosophila [11] show that the expressible Hox genes in a given cell (Figure 2A-right) are in an open chromatin state, characterized by Trithorax (Trx) protein binding, while the non-expressible genes are in a closed chromatin state, characterized by Polycomb (Pc) protein binding (Figure 3). These chromatin states are usually heritable from one cell generation to the next, thereby ensuring that Hox expressibility patterns acquired in the early embryo are faithfully remembered at all later stages, enabling guidance throughout the course of development. At any region along the body, there is typically only one boundary between expressible and non-expressible genes in both mice [9][10] (Figure 2A-right and Figure 3) and Drosophila [11]. In the subtle difference from Lewis’s original proposal, expressible genes need not always be expressed. Expression depends upon the availability of activating or repressive transcription factors and may change in a tissue over developmental time. Expressible Hox genes have been described as “open for business” [12][13]. Regions of the body where Hox genes are non-expressible (closed for business; red zones in Figure 3) typically cannot express these genes at any time.

Figure 3. Discreet domains of open and closed chromatin generally support Lewis’s model. Antibody studies show correspondence between the position of cells along the head–tail axis and the distributions of Hox genes between open (Hox expressible, green domain; Trithorax-rich) and closed (Hox non-expressible, red domain; Polycomb-rich) chromatin states. At each level along the body, there is only a single boundary between these states, supporting Lewis’s model (Figure 2A-right). Re-drawn/modified from Noordermeer et al. [10].

2. Seeking Sense in the Hox Gene Cluster

2.1. Seeking Sense in the Evolutionary Origin of Hox Clustering and Transcriptional Direction

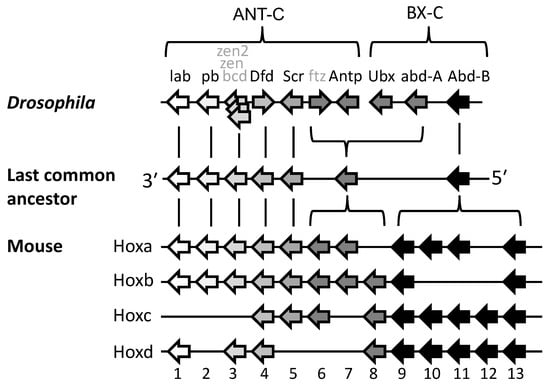

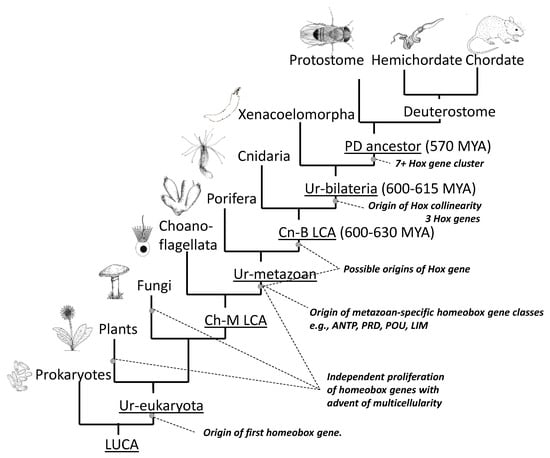

Clustering arose due to gene duplication from an original proto-Hox gene. Duplication occurs due to unequal cross-over of DNA during meiosis in germ cells. This may be due to a cross-over between repeat elements in the DNA, or between other regions of a similar genetic sequence. It results in one chromosome becoming deleted in a genetic fragment—such as a Hox gene in our case—while its attached homologue incorporates the extra fragment. This process, called “tandem gene duplication” leaves one chromosome with both the maternal- and paternal-derived copies of the Hox gene lying in tandem on the same DNA strand, and in the same orientation [14][15][20,21]. If this expanded chromosome contributes to a zygote, then the additional Hox copy offers new scope for evolutionary change. For example, if it acquires a new anterior boundary of expression and function, due to a change in regulation or mutation, then this can specify a new zone of development along the head–tail axis. It is usually suggested that this re-purposing of the new Hox gene occurs after the duplication event [15][21]. However, it has been proposed that two identical Hox genes may provide a selective disadvantage and a more reasonable hypothesis might be that the genes were initially alleles of the same gene that already possessed some useful differences in expression and/or function [16][22]. Repeated cycles of tandem gene duplication then led to the growing Hox gene cluster, permitting ever-increasing complexity of body structures along the head–tail axis. The process neatly explains not only why the Hox genes were formed in clusters, but also why they transcribe in the same direction. The cluster developed with spatial collinearity, and its polarity (that is, whether anterior-expressed genes lie upstream or downstream of posterior genes) was likely established with the initial duplication/re-purposing event [17][23]. Hox genes are members of the ANTP class of homeobox-containing genes. This also includes developmental gene groups paraHox, Dlx and NK, and all are thought to have arisen by tandem duplication from the same ANTP class proto-Hox gene [18][24]. Although paraHox, Dlx and NK genes are now usually dispersed from the Hox cluster some of these remain linked to the Hox cluster in at least some protostome and deuterostome species [18][19][20][21][24,25,26,27]. Apart from the ANTP class genes, there are ten other classes of homeobox genes [18][24], such as PRD, POU and LIM, and all classes likely arose by tandem gene duplication from an original proto-homeobox gene. The question then arises as to when these events took place. Figure 4 indicates the origin of homeobox genes within the tree of life. There are no ANTP class genes outside the metazoa [18][24]. However, duplication and diversification of ANTP class genes must have occurred very early in pre-bilaterian evolution because at least some poriferans (sponges) possess both NK [18][24] and paraHox genes [22][28] even though they lack Hox genes, which are presumed to have been secondarily lost [22][28]. Cnidarians possess Hox, paraHox and NK genes [18], but there is debate over whether cnidarian Hox genes are strict orthologues of bilaterian Hox genes [23], and whether they show spatial collinearity [5](Section 2.9). Proceeding backwards in time, the greatest proliferation of homeobox genes occurred with the advent of multicellularity in animals (metazoa), and also in plants and fungi (Figure 4) [24][29]. Bacteria do not have homeobox genes. However, they do have helix-loop-helix genes which have similarities in structure and function, and which may have been the ancestral progenitors of homeobox genes [24][29].

2.2. Seeking Sense in the Maintenance and Compactness of Clusters

2.2. Seeking Sense in the Maintenance and Compactness of Clusters

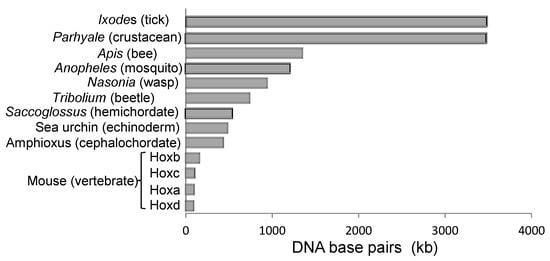

Clusters are not always maintained. Some species may develop splits in the cluster, e.g., Drosophila where splits occur at different positions in separate sub-species [25][30]. However, the large regulatory regions between insect Hox genes probably limit the number of places where clusters can be broken without affecting gene function [26][31]. Other species, such as the urochordate Oikiopleura, show complete dispersal of the Hox cluster throughout the genome though, remarkably, the genes continue to show spatial collinearity in expression relative to the position that they occupied in the ancestral cluster [27][19]. Most species, however, continue to maintain the clustering of their Hox genes, at least to some extent. One explanation for this is enhancer sharing between Hox genes. For example, the iab-5 regulatory region in Drosophila apparently regulates both abd-A and Abd-B [28][32]. Similarly, in mice, the CR3 enhancer regulates both Hoxb4 and Hoxb3 to become expressed up to the level of rhombomere 6/7 [29][33], and a separate Kreisler element then also drives Hoxb3 expression in rhombomere 5 [30][34]. These are examples of local enhancer sharing, where the enhancer lies within the Hox gene cluster. In vertebrates, there are also long-range enhancers, usually located outside the Hox gene cluster, which can loop-in to regulate multiple Hox genes in a tissue-specific way [31][32][35,36]. Long-range enhancers, seen in vertebrates, encourage compaction and exclusion of other, non-Hox, genes. Compact clusters of vertebrates (Figure 5) are likely a derived rather than ancestral condition [32][36].